Sound art

Sound art is an artistic discipline in which sound is utilised as a primary medium. Like many genres of contemporary art, sound art is interdisciplinary in nature, or takes on hybrid forms. Sound art can engage with a range of subjects such as acoustics, psychoacoustics, electronics, noise music, audio media, found or environmental sound, explorations of the human body, sculpture, architecture, film or video and an ever-expanding set of subjects that are part of the current discourse of contemporary art.[1]

In Western art, early examples include Luigi Russolo's Intonarumori or noise intoners, and subsequent experiments by Dadaists, Surrealists, the Situationist International, and in Fluxus happenings. Because of the diversity of sound art, there is often debate about whether sound art falls within the domain of either the visual art or experimental music categories, or both.[2] Other artistic lineages from which sound art emerges are conceptual art, minimalism, site-specific art, sound poetry, electro-acoustic music, spoken word, avant-garde poetry, and experimental theatre.

Origin of the term in the United States

The earliest documented use of the term in the U.S. is from a catalogue for a show called "Sound/Art" at The Sculpture Center in New York City, created by William Hellerman in 1983. The show was sponsored by "The SoundArt Foundation," which Hellerman founded in 1982. The artists featured in the show were: Vito Acconci, Connie Beckley, Bill and Mary Buchen, Nicolas Collins, Sari Dienes and Pauline Oliveros, Richard Dunlap, Terry Fox, William Hellermann, Jim Hobart, Richard Lerman, Les Levine, Joe Lewis, Tom Marioni, Jim Pomeroy, Alan Scarritt, Carolee Schneeman, Bonnie Sherk, Keith Sonnier, Norman Tuck, Hannah Wilke, Yom Gagatzi. The following is an excerpt from the catalogue essay by art historian Don Goddard: "It may be that sound art adheres to curator Hellermann's perception that "hearing is another form of seeing,' that sound has meaning only when its connection with an image is understood... The conjunction of sound and image insists on the engagement of the viewer, forcing participation in real space and concrete, responsive thought rather than illusionary space and thought."[3]

Sound art in Europe

Belgium

The Klankenbos (Sound forest) of Provinciaal Domein Dommelhof is the biggest sound art collection in public space in Europe. In the forest there are 15 sound installation pieces by artists such as Pierre Berthet, Paul Panhuysen, Geert Jan Hobbijn (Staalplaat Soundsystem), Hans van Koolwijk, and others. Yearly in Kortrijk there is the sound art festival Wilde Westen (formerly known as Happy New Ears). In Bruxelles there are QO2 and Overtoon, two organisations that run artist-in-residence programms and organize events. Logos Foundation from Ghent is a sound art org run by Godfried-Willem Raes.

Croatia

In Zadar there is the Sea Organ which plays music by way of sea waves and tubes located underneath a set of large marble steps.

Germany

Originally from Amstrerdam, but moved to Berlin is Staalplaat, a record label focused on sound art and experimental music. Transmediale is a yearly festival focused on media art, covering many sound art performances and installtions.

The Netherlands

The Dutch sound art tradtion started more or less in the Philips Natuurkundig Laboratorium where Dick Raaijmakers worked in the 60s. Paul Panhuysen and Remko Scha developed many early sound art pieces in the 70s and 80s and set up the Apollohuis in Eindhoven. STEIM. WORM, Extrapool are active organisations that have sound art activities. Festival Polderlicht was a sound art festival running from 2000-2015. iii (Instrument Inventors innitiative]] is a The Hague based organisation focused on the creation of sound art pieces. The organisation has an active artist-in-residence programm and continuously invites sound artists to make new works at their location. The Netherlands have three academies where you can study in the direction of sound art Institute of Sonology, Art Science at Royal Academy of Art, The Hague and at the Utrecht School of the Arts in Utrecht.

Norway

Lydgalleriet (The Soundgallery) is a non-commercial gallery for sound based art practices, situated in the centre of Bergen.

Sweden

Playing the Building was an art installation by David Byrne, ex singer of Talking Heads, and Färgfabriken, an independent art venue in Stockholm. Elektronmusikstudion is an active organisation.

United Kingdom

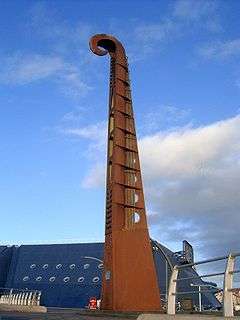

A known sound art pieces in the UK are Blackpool High Tide Organ and Singing Ringing Tree. Although not build as sound art pieces, the UK has several acoustic mirrors along the coastline often explored by field recorders.

Sound art organizations and festivals

- Interval. Sound Actions - Fundació Antoni Tàpies, Barcelona

- SA)) aka www.SoundArtist.ru - largest sound and new media arts community in post-ussr region

- PS-fest aka Podgotovlenniye Sredy - the sound art festival based in Moscow (since 2009)

- New Interfaces for Musical Expression

Gallery

Harry Bertoia, Textured Screen, 1954

Harry Bertoia, Textured Screen, 1954 Panopticon: The Singing Ringing Tree

Panopticon: The Singing Ringing Tree The Blackpool High Tide Organ

The Blackpool High Tide Organ The Cristal Baschet

The Cristal Baschet Yuri Landman, Moodswinger, 2006

Yuri Landman, Moodswinger, 2006

See also

- List of sound artists

- List of topics related to Sound Art

- Acousmonium

- Acoustic ecology

- Work of art

- Audium

- Electronic music

- Fluxus

- Installation art

- Intermedia

- NIME

- Noise Music

- Performance art

- Radio art

- Sonification

- Sound effect

- Sound installation

- Sound poetry

- Sound sculpture

- Soundscape

- Video game music

- Visual music

- Sound map

Notes

References

- Hellerman, William, and Don Goddard. 1983. Catalogue for "Sound/Art" at The Sculpture Center, New York City, May 1–30, 1983 and BACA/DCC Gallery June 1–30, 1983.

- Kahn, Douglas. 2001. Noise, Water, Meat: A History of Sound in the Arts. Cambridge: MIT Press. ISBN 0-262-61172-4.

- Licht, Alan. 2007. Sound Art: Beyond Music, Between Categories (with accompanying compact disc recording). New York: Rizzoli International Publications. ISBN 0-8478-2969-3.

Further reading

- Attali, Jacques. 1985. Noise: The Political Economy of Music, translated by Brian Massumi, foreword by Fredric Jameson, afterword by Susan McClary. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 0-8166-1286-2 (cloth) ISBN 0-8166-1287-0 (pbk.)

- Bandt, Ros. 2001. Sound Sculpture: Intersections in Sound and Sculpture in Australian Artworks. Sydney: Craftsman House. ISBN 1-877004-02-2.

- Cage, John. 1961. "Silence: Lectures and Writings". Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press. (Paperback reprint edition 1973, ISBN 0-8195-6028-6)

- Cox, Christoph. 2003. "Return to Form: Christoph Cox on Neo-modernist Sound Art—Sound—Column." Artforum (November): [pages].

- Cox, Christoph. 2009. "Sound Art and the Sonic Unconscious". Organised Sound 14, no. 1:19–26.

- Cox, Christoph. 2011. "Beyond Representation and Signification: Toward a Sonic Materialism". Journal of Visual Culture 10, no. 2:145-161.

- Cox, Christoph, and Daniel Warner (eds.). 2004. Audio Culture: Readings in Modern Music. New York: Continuum. ISBN 978-0-8264-1615-5.

- Drobnick, Jim (ed.). 2004. Aural Cultures. Toronto: YYZ Books; Banff: Walter Phillips Gallery Editions. ISBN 0-920397-80-8.

- Hegarty, Paul. 2007. Noise Music: A History. New York: Continuum International Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-8264-1726-8 (hardcover) ISBN 978-0-8264-1727-5 (pbk)

- Jensenius, Alexander Refsum; Lyons, Michael, eds. (2017). A NIME Reader: Fifteen Years of New Interfaces for Musical Expression. Springer. ISBN 978-3-319-47214-0.

- Kim-Cohen, Seth. 2009. In the Blink of an Ear: Toward a Non-Cochlear Sonic Art. New York: Continuum. ISBN 978-0-8264-2971-1

- LaBelle, Brandon. 2006. Background Noise: Perspectives on Sound Art. New York and London: The Continuum International Publishing Group. ISBN 0-8264-1844-9 (cloth) ISBN 0-8264-1845-7 (pbk)

- Lander, Dan, and Micah Lexier (eds.). 1990. Sound by Artists. Toronto: Art Metropole/Walter Phillips Gallery.

- Lucier, Alvin, and Douglas Simon. 1980. Chambers. Middletown, Connecticut: Wesleyan University Press. ISBN 0-8195-5042-6.

- Mailman, Joshua B. 2012. "Seven Metaphors for (Music) Listening: DRAMaTIC". Journal of Sonic Studies 2:.

- Nechvatal, Joseph. 2000. "Towards a Sound Ecstatic Electronica". The Thing.

- Oliveros, Pauline. 1984. Software for People. Baltimore: Smith Publications. ISBN 0-914162-59-4 (cloth) ISBN 0-914162-60-8 (pbk)

- Paik, Nam June. 1963. "Post Music Manifesto," Videa N Videology. Syracuse, New York: Everson Museum of Art.

- Peer, René van. 1993. Interviews with Sound Artists. Eindhoven: Het Apollohuis.

- Schaefer, Janek, Bryan Biggs, Christoph Cox, and Sara-Jayne Parsons. 2012. "Janek Schaefer: Sound Art: A Retrospective". Liverpool: The Bluecoat. ISBN 978-0-9538896-8-6.

- Schafer, R. Murray. 1977. The Soundscape. Rochester, Vermont: Destiny Books. ISBN 0-89281-455-1

- Schulz, Berndt (ed.). 2002. Resonanzen: Aspekte der Klangkunst. Heidelberg: Kehrer. ISBN 3-933257-86-7. (Parallel text in German and English)

- Skene, Cameron. 2007. "Sonic Boom". The Montreal Gazette (13 January).

- Toop, David. 2004. Haunted Weather: Music, Silence, and Memory. London: Serpent's Tail. ISBN 1-85242-812-0 (cloth), ISBN 1-85242-789-2 (pbk.)

- Valbonesi, Ilari. A.A.A.A.A.A.A. Cercasi Sound Art. ARTE E CRITICA, ISSUE 64, (2010)

- Wilson, Dan. 2011. "Sonics in the Wildernesses - A Justification." The Brooklyn Rail (April)

- Wishart, Trevor. 1996. On Sonic Art, new and revised edition, edited by Simon Emmerson (with accompanying compact disc recording). Contemporary Music Studies 12. Amsterdam: Harwood Academic Publishers. ISBN 3-7186-5846-1 (cloth) ISBN 3-7186-5847-X (pbk.) ISBN 3-7186-5848-8 (CD recording)