Soka Gakkai International

|

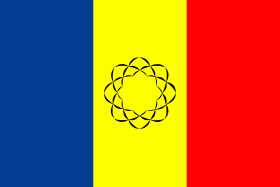

Soka Gakkai International flag | |

| Abbreviation | SGI |

|---|---|

| Formation | January 26, 1975 |

| Headquarters | Tokyo, Japan |

| Location |

|

President |

Daisaku Ikeda (26 January 1975 - ) |

| Affiliations | Soka Gakkai |

| Website |

www |

The Soka Gakkai International (SGI—"Value Creation Association International") is an international Nichiren Buddhist organization founded in 1975 by Daisaku Ikeda.[1] The SGI is the world's largest Buddhist lay organization, with approximately 12 million Nichiren Buddhist practitioners in 192 countries and regions.[2][3] It characterizes itself as a support network for practitioners of Nichiren Buddhism and a global Buddhist movement for "peace, education, and cultural exchange."[4]

The SGI is a non-governmental organization (NGO) with official ties to the United Nations[2] including consultative status with the UNESCO since 1983.[5]

History

The Soka Gakkai International (SGI) was formed at a world peace conference of Nichiren Buddhists on January 26, 1975 on the island of Guam.[6] Representatives from 51 countries attended the meeting and chose Daisaku Ikeda, who served as third president of the Japanese Buddhist organization Soka Gakkai, to become the SGI's founding president.[6]

The SGI was created in part as a new international peace movement, and its founding meeting was held in Guam in a symbolic gesture referencing Guam's history as the site of some of World War II's bloodiest battles, and proximity to Tinian Island, launching place of the atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Japan.[7]

The Soka Gakkai's initial global expansion began after the World War II, when some Soka Gakkai members married mostly American servicemen and moved away from Japan.[8] Expansion efforts gained a further boost in 1960 when Daisaku Ikeda succeeded Jōsei Toda as president of the Soka Gakkai.[9][10] In the first year of his presidency, Ikeda visited the United States, Canada, and Brazil, and the Soka Gakkai's first American headquarters officially opened in Los Angeles in 1963.[9][11]

In the year 2000, the Republic of Uruguay honored the 25th anniversary of the SGI's founding with a commemorative postage stamp. The stamp was issued on October 2, the anniversary of SGI President Ikeda's first overseas journey in 1960.[12]

In January 2015, the director of the Peace Research Institute Oslo reported that the SGI had been nominated for the 2015 Nobel Peace Prize, as confirmed by a Nobel Peace Laureate.[13]

In May 2015, the SGI-USA was one of the organizing groups for the first-ever Buddhist conference at the White House.[14]

In June 2015, the SGI-Italy was recognized by the Italian government with a special accord under Italian Constitution Article 8, acknowledging it as an official religion of Italy and eligible to receive direct taxpayer funding for its religious and social activities. It also recognizes the Soka Gakkai as a "Concordat" (It: "Intesa") that grants the religions status in "a special 'club' of denominations consulted by the government in certain occasions, allowed to appoint chaplains in the army - a concordat is not needed for appointing chaplains in hospitals and jails - and, perhaps more importantly, to be partially financed by taxpayers' money." Eleven other religious denominations share this status.[15][16][17]

Organization

The Soka Gakkai International comprises a global network of affiliated organizations. As of 2011, the SGI reported active national organizations in 192 countries and territories with a total of approximately 12 million members.[2] The SGI is independent of the Soka Gakkai (the domestic Japanese organization), although both are headquartered in Tokyo.[18]

National SGI organizations operate autonomously and all affairs are conducted in the local language.[18] Many national organizations are coordinated by groups such as a women's group, a men's group, and young women's and young men's groups.[19] National organizations generally raise their own operational funds, although the SGI headquarters in Tokyo has awarded funding grants to smaller national organizations for projects such as land acquisition and the construction of new buildings.[19] SGI-affiliated organizations outside Japan are forbidden to engage directly in politics.[19]

While the national organizations are run autonomously, the Tokyo headquarters of SGI disseminates doctrinal and teaching materials to all national organizations around the world.[19] The Tokyo headquarters also serves as a meeting place for national leaders to come together and exchange information and ideas.[19]

The election or nomination of the leaders is typically not decided by the SGI's general membership but by a board of directors.[20] Leadership below national staff, however, has been liberalized; in the United States for instance, the nomination and approval of leaders includes both members and organizational leaders in the process.[21] Dobbelaere notes the election of the presidents,[22] as well as a process of "nomination, review and approval that involves both peers and leaders" in choosing other leaders.[23]

Beliefs and practice

According to Yoichi Kawada, director of the Tokyo-based Institute of Oriental Philosophy, the SGI defines itself as a "movement for contributing to peace, culture and education" based on its "interpretation and practical application of the ideas in the Lotus Sutra."[24]

SGI members practice Nichiren Buddhism as interpreted and applied by the Soka Gakkai's first three presidents: Tsunesaburo Makiguchi, Josei Toda and Daisaku Ikeda.[25] SGI members believe in karma[26] and that the most expedient path to enlightenment is through the practice of Nichiren Buddhism.[18] SGI members identify three basic elements for applying Nichiren Buddhism to daily life: faith, practice, and study.[27]

The daily practice of SGI members centers on chanting the mantra "Nam Myoho Renge Kyo," which translates to "Devotion to the Mystic Law of Cause and Effect through Sound", or "Glory to the Sutra of the Lotus of the Supreme Law."[28][29] Once in the morning and again at night, SGI members do gongyo ("assiduous practice"), during which members chant Nam-myoho-renge-kyo and recite selections from two chapters of the Lotus Sutra, "Expedient Means" (chapter 2) and "The Life Span of the Thus Come One" (chapter 16).[26][27] Gongyo is typically performed in front of a Gohonzon, a scroll considered to be the supreme object of devotion on which is written the daimoku (in other words, Nam-myoho-renge-kyo) and signs of buddhas and bodhisattvas who are prominent in the Lotus Sutra.[30] The Gohonzon itself is housed in a butsudan, an altar that is opened during chanting of Nam-myoho-renge-kyo and gongyo.[31] Nam-myoho-renge-kyo is the name of this potential or Buddha nature within our life. To chant Nam-myoho-renge-kyo, then, is to call forth your Buddha nature. SGI President Daisaku Ikeda once wrote, “Daimoku (Nam-myoho-renge-kyo) is a universal language that is instantly understood by Buddhas.” [32]

SGI members also incorporate social interaction and engagement into their Buddhist practice.[33] Monthly neighborhood discussion meetings are generally held at the homes of SGI members.[27]In the United States, for example, a study characterizes these organizational practices as socially inclusive Buddhism.[34]

Since 1995, the SGI has formally officiated same-sex marriages. In 2008, the SGI-USA, which is headquartered in California, publicly opposed that state's Proposition 8 (which sought to prevent same-sex marriage), and the SGI coordinated with other progressive religious groups to support same-sex couples' right to legally marry.[35][36]

Demographics

The Soka Gakkai International is notable among Buddhist organizations for the racial and ethnic diversity of its members.[18] It has been characterized as the world's largest and most ethnically diverse Buddhist group.[8][10][18][37] Professor Susumu Shimazono suggested several reasons for this: the strongly felt needs of individuals in their daily lives, its solutions to discord in interpersonal relations, its practical teachings that offer concrete solutions for carrying on a stable social life, and its provision of a place where congenial company and a spirit of mutual support may be found.[38] Peter Clarke wrote that the SGI appeals to non-Japanese in part because "no one is obliged to abandon their native culture or nationality in order to fully participate in the spiritual and cultural life of the movement."[39]

In 2015, Italian newspaper la Repubblica reported that half of all Buddhists in Italy are SGI members.[40]

Initiatives promoting peace, culture and education

In 2008, then-High Representative for Disarmament Affairs Sergio Duarte characterized SGI's work toward nuclear disarmament as linking human security with the fundamental goal of eliminating nuclear weapons.[41]

In 2007, the SGI created "The People's Decade" campaign to increase public awareness of the anti-nuclear movement, and help create a global grassroots network of people dedicated to abolishing nuclear weapons.[42][43] In 2014, an SGI youth delegation met with the United Nations Office for Disarmament Affairs (UNODA) regarding coordination of the SGI's efforts and the UN efforts to increase grassroots movements for nuclear abolition.

According to Pax Christi International, on March 28, 2017, a joint statement of Faith Communities Concerned about Nuclear Weapons, initiated by the SGI, was delivered by Pax Christi Philippines during the first UN negotiating conference for a treaty to prohibit nuclear weapons.[44] More than 20 religious leaders affirmed through the joint statement their shared "aspirations for peace and for a world where people live without fear," praising world leaders in attendance for "the courage to begin these negotiations" and calling on States not in attendance to join the June–July session of the conference.[45][46]

The SGI also promotes environmental initiatives through educational activities such as exhibitions, lectures and conferences, and more direct activities such as tree planting projects and the SGI's Amazon Ecological Conservation Center, which is administered by SGI-Brazil.[47] One scholar cites Daisaku Ikeda, SGI's president, describing such initiatives as a Buddhist-based impetus for direct public engagement in parallel with legal efforts to address environmental concerns.[48]

In India, Bharat Soka Gakkai (the SGI of India) debuted the traveling exhibit "Seeds of Hope," a joint initiative of the SGI and Earth Charter International. At the exhibit's opening in Panaji, the state capital of Goa, regional planning head Edgar Ribeiro spoke of lagging efforts to implement environmental laws and stated that "Only a people's movement can take sustainability forward."[49] In Malaysia, Tunku Abdul Rahman University College President Datuk Dr Tan Chik Heok said that this exhibition helped "to create the awareness of the power of a single individual in bringing about waves of positive change to the environment, as well as the society."[50]

In November 2015 SGI signed on to the Buddhist Climate Change Statement representing "over a billion Buddhists worldwide" in a call to action submitted to world leaders at the 21st session of UN climate change talks held in Paris].[51] The statement affirms that Buddhist spirituality compels environmental protection and expresses solidarity with Catholic and Muslim leaders who have taken a similar stance. Described as "one of the most unified calls by a religion's leadership,"[52] the statement draws on the 2009 pan-Buddhist statement, "The Time to Act is Now: A Buddhist Declaration on Climate Change," to which SGI-USA among others became a signatory in early-2015.[53]

Aid work

SGI conducts humanitarian aid projects in disaster-stricken regions. After the 2011 earthquake and tsunami in Japan, local Soka Gakkai facilities became refugee shelters and distribution centers for relief supplies. Efforts also included worldwide fundraising for the victims, youth groups, and spiritual support.[54][55]

In 2014, SGI-Chile members collected supplies to deliver to emergency services and refugee centers after that country's devastating Iquique earthquake.[56]

Interfaith dialogue

In 2015, SGI-USA was part of the organizing committee that convened a day-long conference in Washington, DC of 125 Buddhist leaders to discuss Buddhism and civic activism in the US. The conference identified climate change and the environment, education and peace and disarmament as popular priorities.[57]

Criticism

In 1998, a report by the Select (Enquete) Commission of the German Parliament on new ideological communities stated that although the German branch of SGI was inconspicuous, it could be latently problematic due to its connection with the Soka Gakkai, which was called significant and controversial at the time.[58] The report was criticized as politically biased and, in 1999, Germany's new government coalition rejected the committee's recommendations.[59]

Notable members

Notable members of Soka Gakkai International include:

- Adewale Akinnuoye-Agbaje – British-Nigerian actor best known for his roles on television, including Lost, Oz, and Game of Thrones[60]

- Anne Louise Hassing – Danish actress[61]

- Belinda Carlisle – American singer best known as the lead singer of The Go-Go's[62]

- Brenton Lengel – American playwright and anarchist.[63]

- Buster Williams – American jazz bassist[64]

- Cheryl Boone Isaacs – American film executive and the first African-American president of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences[65]

- Christine Rankin – Former head of the New Zealand Ministry of Social Development and politician[66]

- Claire Bertschinger – British nurse whose work inspired the formation of Live Aid and Band Aid (band)[67]

- Courtney Love – American musician, songwriter, actress, and artist[68]

- Craig Taro Gold – American author, entrepreneur, actor, singer-songwriter, producer, and philanthropist[69]

- Duncan Sheik – American singer-songwriter and composer[70]

- Hank Johnson – United States Congressman for Georgia's 4th congressional district[71]

- Herbie Hancock – American jazz pianist, keyboardist, bandleader, and composer[72]

- Howard Jones – English musician, singer and songwriter[73]

- James Dumont – American actor[74]

- James Lecesne – American actor and writer of the Oscar-winning Trevor (film), co-founder of The Trevor Project[75]

- John Astin – American actor best known for playing Gomez Addams on The Addams Family[72]

- Mariane Pearl – French freelance journalist and former columnist and reporter[76]

- Néstor Torres – American jazz flautist[72]

- Orlando Bloom – British actor known for his roles in film, including The Hobbit trilogy, The Lord of the Rings trilogy, and Troy[77]

- Orlando Cepeda – American former Major League Baseball first baseman and member of the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum[78]

- Patrick Duffy – American actor best known for his roles on television, including Dallas and Step by Step[72]

- Roberto Baggio – Italian footballer and member of the FIFA World Cup Dream Team[79]

- Ron Glass – American actor[80]

- Sabina Guzzanti – Italian satirist, actress, and writer[81]

- Shan Serafin - US film director, screen writer and novelist[82]

- Shunsuke Nakamura – Japanese soccer player, midfielder for the Scottish team Celtic F.C.[83]

- Steven Sater – American playwright, lyricist and screenwriter best known for Spring Awakenings[84]

- Suzanne Vega – American folk singer-songwriter[85]

- Tina Turner – American-Swiss singer, dancer, actress, and author[86]

- Vinessa Shaw – American actress[87]

- Wayne Shorter – American jazz saxophonist and composer[88]

References

- ↑ "Soka Gakkai International". Berkley Center for Religion, Peace, & World Affairs. Retrieved 18 February 2015.

- 1 2 3 Andrew Gebert. "Soka Gakkai". Oxford Bibliographies. Retrieved 18 February 2015.

- ↑ Tricycle Buddhist Review (2015). "No more nukes, Sokka Gakkai International's president calls for nuclear nonproliferation". Retrieved 26 January 2016.

- ↑ Katherine Marshall. Global Institutions of Religion: Ancient Movers, Modern Shakers. Routledge. ISBN 9781136673580.

- ↑ "UN Office for Disarmament Affairs Meets Youth Representatives of Soka Gakkai Japan and of SGI-USA Engaged in Disarmament Issues". United Nations. Retrieved 15 August 2015.

- 1 2 N. Radhakrishnan. The Living Dialogue: Socrates to Ikeda. Gandhi Media Centre. OCLC 191031200.

- ↑ Ramesh Jaura. "SPECIAL REPORT: Peace Impulses from Okinawa". Global Perspectives. Retrieved 18 February 2015.

- 1 2 Gary Laderman (2003). Religion and American Cultures: An Encyclopedia of Traditions, Diversity, and Popular Expressions. ABC CLIO. ISBN 9781576072387.

- 1 2 Ronan Alves Pereira (2008). "The transplantation of Soka Gakkai to Brazil: building "the closest organization to the heart of Ikeda-Sensei"". Japanese Journal of Religious Study.

- 1 2 Clark Strand (Winter 2008). "Faith in Revolution". Tricycle. Retrieved 18 February 2015.

- ↑ Charles Prebish (1999). Luminous Passage: The Practice and Study of Buddhism in America. University of California Press. ISBN 9780520216976.

- ↑ "Sello - 1975-2000 Soka Gakkai Internacional 25º Aniversario". Correo Uruguayo. Retrieved 3 February 2016.

- ↑ "Nobel Peace Prize 2015: PRIO Director's Speculations". PRIO. Retrieved 10 August 2015.

- ↑ "U.S., Buddhist Leaders to Meet at the White House". Washington Post. Retrieved 10 August 2015.

- ↑ Introvigne, Massimo. "Italy signs Concordat with Soka Gakkai". Cesnur.org. CESNUR.

- ↑ "Religion in the Italian Constitution". Georgetown University. Retrieved 10 August 2015.

- ↑ "Istituto Buddista Italiano Soka Gakkai". Governo Italiano. Retrieved 14 August 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Daniel Métraux (2013). "Soka Gakkai International: The Global Expansion of a Japanese Buddhist Movement". Religion Compass.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Daniel Métraux (2013). "Soka Gakkai International: Japanese Buddhism on a Global Scale". Virginia Review of Asian Studies.

- ↑ http://constitution-sgic.org/PDFs/G3%20policy%20on%20leaders%20-%202014%2009%2027.PDF Governance Policy #3 - Leaders

- ↑ Dobbelaere, Karel (1998). Soka Gakkai. Signat.

- ↑ Dobbelaere, Karel. Soka Gakkai. p. 9.

"H. Hojo. . . was elected president. Ikeda became honorary president. . . At the death of Hojo in 1981, E. Akiya was elected president. . ." . .

- ↑ Dobbelaere, Karel. Soka Gakkai. p. 78.

- ↑ Kawada, Yoichi (2009). "The SGI Within the Historical Context of Buddhism—and Its Philosophical Basis" (pdf). The Journal of Oriental Studies. 19: 103. Retrieved April 26, 2017.

- ↑ Noriyoshi Tamaru. Soka Gakkai In Historical Perspective: in Global Citizens. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-924039-6.

- 1 2 Georgye D. Chryssides; Margaret Wilkins. A Reader in New Religious Movements: Readings in the Study of New Religious Movements. Bloomsbury Academic. ISBN 0826461689.

- 1 2 3 Robyn E. Lebron. Searching For Spiritual Unity...Can There Be Common Ground. CrossBooks. ISBN 1462712622.

- ↑ SGDB 2002, Lotus Sutra of the Wonderful Law

- ↑ Kenkyusha (1991). Kenkyusha's New Japanese-English Dictionary. Tokyo: Kenkyusha Limited. ISBN 4-7674-2015-6.

- ↑ Richard Hughes Seager. Buddhism in America. Columbia University Press. ISBN 0231108680.

- ↑ Elisabeth Arweck. Theorizing Faith: The Insider/Outsider Problem in the Study of Ritual. Bloomsbury Academic. ISBN 1902459334.

- ↑ http://www.sgi-usa.org/basics-of-buddhism/

- ↑ Karel Dobbelaere. Soka Gakkai: From Lay Movement to Religion. Signature Books. ISBN 1560851538.

- ↑ Chappell, David (2000). "Chapter 11: Socially Inclusive Buddhists in America". In Machacek, David; Wilson, Bryan. Global Citizens: The Soka Gakkai Buddhist Movement in the World. Oxford University Press. pp. 299–325. ISBN 0-19-924039-6.

- ↑ "U.S. Buddhist Group Approves Marriage Rites for Gays". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 21 January 2016.

- ↑ "Mormons urged to back ban on same sex marriage". SF Gate. Retrieved 21 January 2016.

- ↑ Daniel Burke (24 February 2007). "Diversity and a Buddhist Sect". The Washington Post. Retrieved 18 February 2015.

- ↑ Susumu Shimazono (1991). "The Expansion of Japan's New Religions into Foreign Cultures". Japanese Journal of Religious Studies.

- ↑ Peter B. Clarke (2000). "'Success' and 'Failure': Japanese New Religions Abroad". Japanese New Religions in Global Perspective. Curzon Press. ISBN 0700711856.

- ↑ "La Soka Gakkai entra nell'8x1000, Renzi a Firenze firma l'intesa con l'istituto buddista". Repubblica. Retrieved 10 August 2015.

- ↑ Duarte, Sergio (30 April 2008). "Opening Remarks" (pdf). United Nations. Retrieved 11 March 2016.

- ↑ "People's Decade for Nuclear Ambition". People's Decade. Retrieved 15 August 2015.

- ↑ "Five Million Voices for Nuclear Zero". Waging Peace. Retrieved 15 August 2015.

- ↑ "Watch: Interfaith statement delivered at UN nuclear weapons negotiations". Independent Catholic News (ICN). 2017-03-29. Retrieved 2017-03-30.

- ↑ Kenny, Peter (2017-04-02). "Faith groups call for action at UN atomic weapons' talks that nuclear-armed nations boycott". Ecumenical News. Retrieved 2017-04-03.

- ↑ Faith Communities Concerned about Nuclear Weapons (March 2017). "Public Statement to the First Negotiation Conference for a treaty to prohibit nuclear weapons leading to their elimination" (pdf) (Statement). Retrieved 2017-04-03.

- ↑ Dessì, Ugo (2013). "'Greening Dharma': Contemporary Japanese Buddhism and Ecology". JSRNC. Equinox Publishing, Ltd. 7 (3): 339–40. doi:10.1558/jsrnc.v7i3.334. Retrieved March 2, 2016.

- ↑ Dessì, Ugo (2013). "'Greening Dharma': Contemporary Japanese Buddhism and Ecology". JSRNC. Equinox Publishing, Ltd. 7 (3): 340. doi:10.1558/jsrnc.v7i3.334. Retrieved March 2, 2016.

- ↑ Ribeiro, Edgar (2016-02-12). "Edgar Riberio pushes for mapping Goa". Times of India. Retrieved 2016-03-02.

- ↑ "Sowing the seeds of hope". The Star online. 2014-11-16. Retrieved 2016-03-02.

- ↑ "Buddhist Climate Change Statement to World Leaders" (PDF). Global Buddhist Climate Change Collective. November 25, 2015. Retrieved May 4, 2016.

- ↑ Schouten, Lucy (October 30, 2015), "Why climate change unites Buddhists around the world", The Christian Science Monitor, retrieved May 4, 2016

- ↑ "A Buddhist Declaration on Climate Change". Ecological Buddhism: A Buddhist Response to Global Warming. Retrieved May 4, 2016.

- ↑ "Sendai UN Disaster Panel.". Pan Orient News. Retrieved 15 February 2016.

- ↑ "Grassroot responses to the Tohoku earthquake of 11 March 2011." (PDF). Anthropology Today Vol. 28, June 2012. Retrieved 15 February 2016.

- ↑ "Yes, Religion Can Still Be A Force For Good In The World. Here Are 100 Examples How". The Huffington Post. Retrieved 5 February 2016.

- ↑ Boorstein, Michelle (2015-05-12). "A political awakening for Buddhists? 125 U.S. Buddhist leaders to meet at the White House". The Washington Post. Retrieved 2017-05-17.

- ↑ Endbericht der Enquete-Kommission Sogenannte Sekten und Psychogruppen, Page.105 (PDF; 6,5 MB)|quote=Some groups have little significance nationally, they are not involved locally in any serious political controversy and/or have attracted little public censure. Nevertheless, they remain a latent problem through being linked to international organisations that are significant and controversial elsewhere. One such example came to light at the hearing with Soka Gakkai, which in Germany is a fairly inconspicuous group, but is highly significant in Japan, the United States, and elsewhere. (Translated at http://www.csj.org/infoserv_articles/german_enquete_commission_report.htm)

- ↑ Seiwert, Hubert (2004). Richardson, James T., ed. Regulating Religion Case Studies from Around the Globe. Boston, MA: Springer US. pp. 85–102. ISBN 9781441990945.

- ↑ Mark Sachs (7 August 2009). "Adewale Akinnuoye-Agbaje not lost in L.A.". The Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 18 February 2015.

- ↑ Steinthal, Vibeke (April 2011). "Skuespilleren Anne Louise Hassing: "Vi Har Alle En Mission"" (PDF). Liv & Sjæl (in Danish): 31–35. Retrieved 26 January 2016.

- ↑ Lips Are Sealed: A Memoir. Google Books. Retrieved 16 March 2015.

- ↑ "Interview With Brenton Lengel". The Fifth Column. Retrieved 2017-01-07.

- ↑ Ben Ratliff (22 February 2007). "Celebrating a Saxohonist's Art and Heart". The New York Times. Retrieved 18 February 2015.

- ↑ name="elementsofstyle-isaacs"Blaine Charles (12 March 2014). "Celebrating Diversity". Retrieved 16 March 2015.

- ↑ Claire Harvey (31 December 2005). "Free-range soul searching replacing organized religion in NZ". The New Zealand Herald. Retrieved 18 February 2015.

- ↑ Andrew Heavens (29 January 2005). "Journey from famine to the hunger of the soul". The Times (UK). Retrieved 18 February 2015.

- ↑ Charlie Ulyatt (9 January 2007). "The Chanting Buddhas". BBC. Retrieved 18 February 2015.

- ↑ Gold, Taro. "A Golden Renaissance: Renaissance Man Taro Gold". Retrieved 15 February 2016.

- ↑ Jeremy Cowart (30 January 2007). "Sheik scores on Broadway". USA Today. Retrieved 18 February 2015.

- ↑ Sarah Wheaton (2 January 2007). "A Congressman, a Muslim and a Buddhist Walk Into a Bar...". The New York Times. Retrieved 18 February 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 James D. Davis (24 May 1996). "Enriching The Soul". The Sun-Sentinel. Retrieved 18 February 2015.

- ↑ Jones, Howard. "Howard On Buddhism". Retrieved 16 March 2015.

- ↑ "Jurassic World actor James DuMont talks Nichiren Buddhism and "a deeper shade of blue."".

- ↑ "James Lecesne". Speaker Profile. Retrieved 16 March 2015.

- ↑ Bill Broadway (23 March 2002). "Widow's Strength Inspires Faithful: Public Statements Demonstrate Pearl's Buddhist Beliefs". the Washington Post.

- ↑ Staff (1 December 2011). "Miranda Kerr Chants With Baby Flynn And Husband Orlando Bloom!". Hollywood Life. Retrieved 18 February 2015.

- ↑ Orlando Cepeda (1998). "Baby Bull: From Hardball to Hard Time and Back". Taylor Trade Publishing. ISBN 9781461625131.

- ↑ Sandro Magister (4 September 1997). "Budddisti Soka Gakkai. Una Sabina vi con convertirà". Espress Online (in Italian). Retrieved 18 February 2015.

- ↑ Ron Glass biography, RealityTVWorld.com, accessed 7 October 2015

- ↑ Sandro Magister (2 December 2008). "Buddhisti Soka Gakkai". Espress Online. Retrieved 15 October 2015.

- ↑ "Shan Serafin: Biography". IMDb.com, Inc. n.d. Retrieved 2017-07-05.

- ↑ Minoru Matsutani (2 December 2008). "Soka Gakkai keeps religious, political machine humming". The Japan Times. Retrieved 18 February 2015.

- ↑ Joyce Walder (14 December 2006). "Storming Broadway From Atop a Fortress". The New York Times. Retrieved 18 February 2015.

- ↑ Maggie Farley (26 March 1995). "Japan Sects Offer Personal Path in Rudderless Society". The Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 18 February 2015.

- ↑ Andrea Miller (March 2016). "What's Love Got to Do With It?". Lion's Roar Magazine. Retrieved 2 March 2016.

- ↑ Performance: Vinessa Shaw, by Michael Ordona, February 12, 2009, Los Angeles Times

- ↑ Nate Chinen (31 January 2013). "Major Jazz Eminence, Little Grise". The New York Times. Retrieved 18 February 2015.

Further reading

- Causton, Richard: The Buddha in Daily Life: An Introduction to the Buddhism of Nichiren Daishonin. Rider, 1995; ISBN 978-0712674560

- Seager, Richard: Encountering the Dharma: Daisaku Ikeda, Soka Gakkai, and the Globalization of Buddhist Humanism. University of California Press, 2006; ISBN 978-0520245778

- Strand, Clark: Waking the Buddha: How the Most Dynamic and Empowering Buddhist Movement in History Is Changing Our Concept of Religion. Middleway Press, 2014; ISBN 978-0977924561

External links

Official SGI websites

- sgi.org – Official SGI website

- sgiquarterly.org – Official website of the SGI Quarterly Magazine

- peoplesdecade.org – Official website of the People's Decade for Nuclear Abolition

- commonthreads.sgi.org – Official website of the Common Threads blog for building a culture of peace

- sgi.org/ru – Official SGI website in the Russian language

Affiliate websites

- sgi-usa.org – Official website of the SGI-USA

- sgi-uk.org – Official website of the SGI-UK

- hksgi.org – Official website of the SGI-Hong Kong

- ssabuddhist.org – Official website of the SGI-Singapore

- sgicanada.org – Official website of the SGI-Canada

- sgiaust.org – Official website of the SGI-Australia

- sginz.org – Official website of the SGI-New Zealand

- bharatsokagakkai.org – Official website of the Bharat Soka Gakkai (SGI of India)