Soho

| ||||||

| Soho Top from left: Greek Street, Ronnie Scott's Jazz Club. Middle from left: Comptons, Kingly Court. Bottom from left: View of Soho, Gardener's hut, Soho Square. |

Soho is an area of the City of Westminster and is part of the West End of London. Long established as an entertainment district, for much of the 20th century Soho had a reputation as a base for the sex industry in addition to its night life and its location for the headquarters of leading film companies. Since the 1980s, the area has undergone considerable gentrification. It is now predominantly a fashionable district of upmarket restaurants and media offices, with only a small remnant of sex industry venues.

Soho is a small, multicultural area of central London; a home to industry, commerce, culture and entertainment, as well as a residential area for both rich and poor. It has clubs, including the former Chinawhite nightclub; public houses; bars; restaurants; a few sex shops scattered amongst them; and late-night coffee shops that give the streets an "open-all-night" feel at the weekends. Record shops cluster in the area around Berwick Street, with shops such as Phonica, Sister Ray and Reckless Records.

On many weekends, Soho is busy enough to warrant closing off some of the streets to vehicles. Westminster City Council pedestrianised parts of Soho in the mid-1990s, but later removed much of the pedestrianisation, apparently after complaints of loss of trade from local businesses.

Toponymy

The name "Soho" first appears in the 17th century. Most authorities believe that the name derives from a former hunting cry.[1][2] James Scott, 1st Duke of Monmouth, used "soho" as a rallying call for his men at the Battle of Sedgemoor on 6 July 1685,[3] half a century after the name was first used for this area of London. The Soho name has been imitated by other entertainment and restaurant districts such as the Soho, Hong Kong entertainment zone; the cultural and commercial area of Soho in Málaga; the office and retail skyscraper development of Wangjing SOHO in suburban Beijing; the SoHo (South of Horton) neighbourhood in London, Ontario, Canada; and the fashionable area of Palermo Soho in Buenos Aires. The New York City neighborhood of SoHo, Manhattan gets its name from its location SOuth of HOuston Street, but is also a reference to London's Soho.[4]

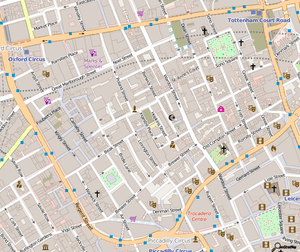

Location

Soho has an area of about one square mile (2.5 km2), and is now usually considered to be the area bounded by Oxford Street to the north, Regent Street to the west, Leicester Square to the south and Charing Cross Road to the east. However, apart from Oxford Street, all of these roads are 19th-century metropolitan improvements, so they are not Soho's original boundaries. Soho has never been an administrative unit, with formally defined boundaries. The area to the west is known as Mayfair, to the north Fitzrovia, to the east St Giles and Covent Garden, and to the south St James's. According to the Soho Society, Chinatown, the area between Leicester Square to the south and Shaftesbury Avenue to the north, is part of Soho, although some consider it a separate area. Soho is part of the West End electoral ward which elects three councillors to Westminster City Council.

History

Early history

What is now Soho was farmland during the Middle Ages that belonged to the Abbot and Convent of Abingdon and the master of Burton St Lazar Hospital in Leicestershire, who managed a leper hospital in St Giles in the Fields.[5] In 1536, the land was taken by Henry VIII as a royal park for the Palace of Whitehall. The area south of what is now Shaftesbury Avenue did not stay in the Crown possession for long. Queen Mary sold around 7 acres (2.8 ha) in 1554, and most of the remainder was sold between 1590 and 1623. A small 2-acre (0.81 ha) section of land remained, until sold by Charles II in 1676.[6]

In the 1660s, ownership of Soho Fields passed to Henry Jermyn, 1st Earl of St Albans, who leased 19 out of the 22 acres (89,000 m2) of land to Joseph Girle. He was granted permission to develop property and quickly passed the lease and development to bricklayer Richard Frith.[7] Much of the land was granted freehold in 1698 by William III to William Bentinck, 1st Earl of Portland, while the southern part of Soho was sold piecemeal in the 16th and 17th centuries, partly to Robert Sidney, Earl of Leicester.[6]

Soho was part of the ancient parish of St Martin in the Fields, forming part of the Liberty of Westminster. As the population started to grow a new church was provided and in 1687 a new parish of St Anne was established for it. The parish stretched from Oxford Street in the north, to Leicester Square in the south and from what is now Charing Cross Road in the east to Wardour Street in the west. It therefore included all of contemporary eastern Soho, including the Chinatown area.[8] The western portion of modern Soho, around Carnaby Street was part of the parish of St James, that was split off from St Martin in 1686.[6]

Gentrification

Building progressed rapidly in the late 17th century, with large properties including Monmouth House, Leicester House, Fauconberg House, Carlisle House and Newport House.[5]

Soho Square was first laid out in the 1680s on the former Soho Fields. Firth built the first houses around the square, and by 1691, 41 had been completed. It was originally called King Square in honour of Charles II, and a statue of him was based in the centre. Several upper-class families moved into the area. The square had become known as Soho Square by 1720, at which point it had fashionable houses around all sides.[7] Only two houses from this period survived to the 21st century, No 10 and No 15.[9]

Cholera outbreak

A significant event in the history of epidemiology and public health was Dr. John Snow's study of an 1854 outbreak of cholera in Soho.[10] He identified the cause of the outbreak as water from the public water pump located at the junction of Broad Street (now Broadwick Street) and Cambridge Street (now Lexington Street), close to the rear wall of what is today the John Snow public house.

John Snow mapped the addresses of the sick, and noted that they were mostly people whose nearest access to water was the Broad Street pump. He persuaded the authorities to remove the handle of the pump, thus preventing any more of the infected water from being collected. The spring below the pump was later found to have been contaminated with sewage. This is an early example of epidemiology, public health medicine and the application of science—the germ theory of disease—in a real-life crisis.[11] Science writer Steven Johnson has written about the changes related to the cholera outbreak, and notes that almost every building on the street that existed in 1854 has since been replaced.[12]

A replica of the pump, with a memorial plaque and without a handle (to signify John Snow's action to halt the outbreak) was erected near the location of the original pump.

Decline

Though the Earls of Leicester and Portland had intended Soho to be an upper class estate comparable to Bloomsbury, Marylebone and Mayfair, Soho never developed as such. Immigrants began to settle in the area from around 1680 onwards, particularly French Huguenots after 1688. The area became known as London's French quarter.[13] The French church in Soho Square was founded by Huguenots and opened on 25 March 1893, with a coloured brick and terracotta facade designed by Aston Webb.[14]

By the mid-18th century, the aristocrats who had been living in Soho Square or Gerrard Street had moved away, as more fashionable areas such as Mayfair became available.[9] The historian and topographer William Maitland wrote the parish "so greatly abound with French that is an easy Matter for a Stranger to imagine himself in France."[5] Soho's character stems partly from the ensuing neglect by rich and fashionable London, and the lack of redevelopment that characterised the neighbouring areas.

The aristocracy had mostly disappeared from Soho by the 19th century, to be replaced by prostitutes, music halls and small theatres. The population increased significantly, reaching 327 inhabitants per acre by 1851, making the area one of the most densely populated areas of London. Houses became divided into tenements with chronic overcrowding and disease. A serious outbreak of cholera in 1854 around Soho caused the remaining upper-class families to leave the area. Numerous hospitals were built to cope with the health problem, with six being constructed between 1851 and 1874.[5] Businesses catering to household essentials were established at the same time.[15]

The restaurant trade in Soho improved dramatically in the early 20th century. The construction of new theatres along Shaftesbury Avenue and Charing Cross Road improved the reputation of the area, and a meal for theatre-goers became common.[5] Public houses in Soho increased in popularity during the 1930s, and were filled with struggling authors, poets and artists.[16]

A detailed mural depicting Soho characters, including writer Dylan Thomas and jazz musician George Melly, is in Broadwick Street, at the junction with Carnaby Street. In fiction, Robert Louis Stevenson had Dr. Henry Jekyll set up a home for Edward Hyde in Soho in his novel, Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde.[17] Joseph Conrad used Soho as the home for The Secret Agent, a French immigrant who ran a pornography shop.

Recent history

On 30 April 1999, the Admiral Duncan pub on Old Compton Street, which serves the gay community, was damaged by a nail bomb that left three dead and 30 injured. The bomb was the third that had been planted by David Copeland, a neo-Nazi who was attempting to stir up ethnic and homophobic tensions by carrying out a series of bombings.[18]

Properties

Restaurants

Many small and easily affordable restaurants and cafes were established in Soho during the 19th century, particularly as a result of Greek and Italian immigration. The restaurants were not looked upon favourably at first, but their reputation changed at the start of the 20th century. In 1924, a guide reported "of late years, the inexpensive restaurants of Soho have enjoyed an extraordinary vogue."[5] Arthur Ransome has two chapters of Bohemia in London (1907) about Old and New Soho, and about Soho coffee-houses like the Orange, The Moorish Café and The Algerian.

Theatre and film

Soho is near the heart of London's theatre area. It is home to Soho Theatre, built in 2000 to present new plays and comedy. Gerrard Street is the centre of London's Chinatown, a mix of import companies and restaurants (including—until 2015 when it closed—Lee Ho Fook's, mentioned in Warren Zevon's song "Werewolves of London"). Pinball Wizard, one of the most famous songs by The Who and subsequently covered by Elton John, contains the line "From Soho down to Brighton, I must've played them all", in reference to the locations frequented by the title character. Street festivals are held throughout the year, most notably on the Chinese New Year.

The Windmill Theatre was based on Great Windmill Street, and was named after a windmill at this location that was demolished in the 18th century. It initially opened as the Palais de Luxe in 1910 as a small cinema, but was unable to compete with larger venues and was converted into a theatre by Howard Jones. It re-opened in December 1931, but was still unsuccessful. In 1932, the general manager Vivian Van Damm introduced a non-stop variety show throughout the afternoon and evening. It was famous for its nude tableaux vivants, in which the models had to remain motionless to avoid the censorship laws then in place. The theatre claimed that, aside from a compulsory closure between 4 and 16 September 1939, it was the only theatre in London which did not close during World War II, leading to the slogan "We never closed". Several prominent comedians including Harry Secombe, Jimmy Edwards and Tony Hancock began their careers at the Windmill. It closed on 31 October 1964 and was again turned into a cinema.[19][20]

The Raymond Revuebar was a small theatre specialising in striptease and nude dancing. It was owned by Paul Raymond and opened in1958. The most striking feature of the Revuebar was the huge brightly lit sign declaring it to be the "World Centre of Erotic Entertainment." Raymond subsequently bought the lease of the Windmill and ran it as a "nude entertainment" venue until 1981.[21]

In the early eighties, the upstairs became known as the Boulevard Theatre. It was used as a comedy club called "The Comic Strip" by a small group of alternative comedians[22] before they found wider recognition with the series The Comic Strip Presents on Channel 4. It was also used as a "straight" theatre venue for a series of play premieres that included Diary of a Somebody (the Joe Orton diaries) by John Lahr, a rock opera version of Macbeth by Howard Goodall and The Lizard King (the Jim Morrison play) by Jay Jeff Jones, and a rare theatrical appearance by Nicole Kidman memorably reported as "pure theatrical viagra".

The name and control of the theatre (but crucially, not the property itself) were bought by Gerald Simi in 1997. Gradually the theatre's fortunes waned, with Simi citing rising rent demands from Raymond as the cause, until the Revuebar closed on 10 June 2004. It became a gay bar and cabaret venue called Too2Much, changed its name to Soho Revue Bar in 2006 with a launch party including performances by Boy George, Antony Costa and Marcella Detroit, but the Revue Bar closed in 2009.

Soho is a centre of the independent film and video industry as well as the television and film post-production industry. The British Board of Film Classification, formerly known as the British Board of Film Censors, can be found in Soho Square. Soho's key fibre communications network is managed by Sohonet, which connects the Soho media and post-production community to British film studio locations such as Pinewood Studios and Shepperton Studios and other major production centres across the globe, including London, Paris, Barcelona, Amsterdam, Rome, New York City, Los Angeles, Vancouver, Toronto, Sydney, Brisbane, Melbourne, Wellington and Auckland. There are also plans by Westminster Council to deploy high-bandwidth Wi-Fi networks in Soho as part of a programme to further encourage the development of the area as a centre for media and technology industries. Recent research commissioned by Westminster City Council shows that 23% of the workforce in Soho works in the creative industries, making it one of the most creative square miles in the world.[23]

Radio

Soho Radio commenced live broadcasting on 7 May 2014[24] on Great Windmill Street, next to the Windmill Club. Primarily a radio station, Soho Radio broadcasts 24 hours streaming live and pre-recorded programming from its premises, and also functions as a retail space and coffee shop. The station states on its website that it aims "to reflect the culture of Soho through our vibrant and diverse content."[25]

Religion

Soho is home to numerous religious and spiritual groups, notably St Anne's Church on Dean Street (damaged by a V1 flying bomb during World War II, and re-opened in 1990), the Church of Our Lady of the Assumption and St Gregory on Warwick Street (the only remaining 18th century Roman Catholic embassy chapel in London and principal church of the Personal Ordinariate of Our Lady of Walsingham), St Patrick's Church in Soho Square (founded by Irish immigrants in the 19th century), City Gates Church with their centre in Greens Court, the Hare Krishna Temple off Soho Square and a small mosque on Berwick Street. The French Protestant Church of London, the only of its kind in the city, is found in Soho.

Music

The music scene in Soho can be traced back to 1948 and Club Eleven, generally regarded as the first venue where modern jazz, or bebop, was performed in the UK. The Harmony Inn was a hang-out for musicians on Archer Street operating during the 1940s and 1950s. It stayed open very late and attracted jazz fans from the nearby Cy Laurie Jazz Club.

The Ken Colyer Band's 51 Club, a venue for traditional jazz, opened on Great Newport Street in the early fifties. Blues guitarist and harmonica player Cyril Davies and guitarist Bob Watson launched the London Skiffle Centre, London's first skiffle club, on the first floor of the Roundhouse pub on Wardour Street in 1952.

In the early 1950s, Soho became the centre of the beatnik culture in London. Coffee bars such as Le Macabre on Wardour Street, which had coffin-shaped tables, fostered beat poetry, jive dance and political debate. The Goings On, located in Archer Street, was a Sunday afternoon club, organised by beat poets Pete Brown, Johnny Byrne and Spike Hawkins, that opened in January 1966. For the rest of the week, it operated as an illegal gambling den. Other "beat" coffee bars in Soho included the French, Le Grande, Stockpot, Melbray, Universal, La Roca, Freight Train (Skiffle star Chas McDevitt's place), El Toro, Picasso, Las Vegas, and the Moka Bar.

The 2i's Coffee Bar was probably the first rock club in Europe, opened in 1956 (59 Old Compton Street), and soon Soho was the centre of the fledgling rock scene in London. Clubs included the Flamingo Club, La Discothèque, Whisky a Go Go, Ronan O'Rahilly's The Scene in 1963 (near the Windmill Theatre in Ham Yard – formally The Piccadilly Club) and jazz clubs like Ronnie Scott's, which opened in 1959 at 39 Gerrard Street and moved to 47 Frith Street in 1965.

Soho's Wardour Street was the home of the Marquee Club, which opened in 1958 and where the Rolling Stones first performed in July 1962. Eric Clapton and Brian Jones both lived for a time in Soho, sharing a flat with future rock publicist, Tony Brainsby.[26]

Soho was also home to Trident Studios at 17 St Anne's Court between 1968 and 1981 where recording artists included The Beatles, The Who, Elton John, Queen and David Bowie.

Although technically not part of Soho, the adjacent Denmark Street is known for its connections with British popular music, and is nicknamed the British Tin Pan Alley due to its large concentration of shops selling musical instruments.[27] The Sex Pistols lived beneath number 6 Denmark Street, and recorded their first demos there. Jimi Hendrix, the Rolling Stones and David Bowie have all recorded there[28] and Elton John wrote his hit "Your Song" in the street.[29] Gerrard Street in Soho is the location where a nascent Led Zeppelin first rehearsed/performed together in a secluded basement room upon their formation in 1968.

Fashion

Carnaby Street emerged from being an insignificant side-street in Soho when the first boutiques opened in 1957. It became the centre point of British fashion in the 1960s, which subsequently acquired a worldwide reputation. It remains a popular place for the fashion trade into the 21st century.[30]

Sex industry

The Soho area has been at the heart of London's sex industry for over 200 years; between 1778 and 1801 21 Soho Square was location of the White House, a brothel described by the magistrate Henry Mayhew as "a notorious place of ill-fame".[31]

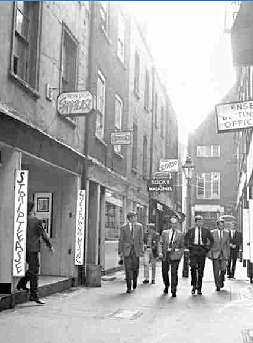

Before the Street Offences Act 1959 became law, prostitutes packed Piccadilly Circus and the streets and alleys around Soho. By the early 1960s the area was home to nearly a hundred strip clubs and almost every doorway in Soho had red-lit doorbells, or open doors with little postcards just inside advertising "Large Chest for Sale" or "French Lessons Given." These are known as walk-ups. Brothels, unlike prostitution, have long been illegal under English law, and licences to supply alcoholic drinks will not be granted against police objections. Thus, other than more or less respectable hotels where independent sex trade may be discreetly conducted, lavish brothels cannot be established. The low end of the legal sex trade generally depended upon streetwalkers picking up clients on the street and taking them back to cheap rooms. When the Act drove prostitution off the streets, many clubs such as the Blue Lagoon became fronts for prostitution.

In 1960, London's first sex cinema, the Compton Cinema Club (a members-only club to get around the law) opened at 56 Old Compton Street. It was owned by Michael Klinger and Tony Tenser who later produced two early Roman Polanski films, including Repulsion (1965).[32] Michael Klinger also owned the Heaven and Hell hostess club (which had earlier been just a beatnik club) across the road and a few doors down from the 2I's on the corner of Old Compton Street and Dean Street.

As post-Second World War austerity relaxed into the "swinging '60s", clip joints also surfaced; these unlicensed establishments sold coloured water as champagne with the promise of sex to follow, thus fleecing tourists looking for a "good time."

Harrison Marks, a "glamour photographer" and girlie magazine publisher, had a photographic gallery located at No. 4 Gerrard Street and published several salacious magazines such as Kamera, which were published from the late 1950s until 1968. The model Pamela Green prompted him to take up nude photography, and she remained the creative force in their business until their professional relationship ended in 1967. The content, however, by today's standard is tame.

By the 1970s, the sex shops had grown from the handful opened by Carl Slack in the early 1960s. From 1976 to 1982, Soho had 54 sex shops, 39 sex cinemas and cinema clubs, 16 strip and peep shows, 11 sex-orientated clubs and 12 licensed massage parlours.[33] In 1983 there were a total of 59 sex shops[34] some with nominally "secret" backrooms selling hardcore photographs and novels, including Olympia Press editions. By this time the sex industry dominated Soho's square mile.

The growth of the sex industry in Soho in the late '60s early '70s owed much to corruption in the Metropolitan Police. The Metropolitan Police Vice squad at that time suffered from corrupt police officers involved with enforcing organised crime control of the area, and simultaneously accepting "back-handers" or bribes. However, exposés in the newspapers and the appointment of Robert Mark as Chief Constable saw this change. In 1972, local residents started the Soho Society in order to control the increasing expansion of the sex industry in the area and improve it with a comprehensive redevelopment plan. This led to a series of corruption trials in 1975, following which several senior police officers were imprisoned.[5] This caused something of a mini recession in Soho which depressed property values at the time Paul Raymond had started buying freeholds there.[35]

By the 1980s, purges of the police force along with pressure from the Soho Society and new and tighter licensing controls by the City of Westminster led to a crackdown on illegal premises. The number of sex industry premises dropped from 185 in 1982 to around 30 in 1991.[7] By 2000, a substantial relaxation of general censorship, the ready availability of non-commercial sex, and the licensing or closing of unlicensed sex shops had reduced the red-light area to just a small area around Brewer Street and Berwick Street, in property largely owned or controlled by the holdings of Paul Raymond, whose legitimate business Raymond's Revuebar had increasingly and conspicuously dominated the red-light area and its trade for decades. Soho has fifteen licensed sex shops and several remaining unlicensed ones. Several strip clubs in the area were reported in London's Evening Standard newspaper in February 2003 to be rip-offs (known as clip joints), aiming to intimidate customers into paying for absurdly over-priced drinks and very mild 'erotic entertainment'.

Although several walk-ups on streets leading off Shaftesbury Avenue were bought up and closed or renovated for other uses during the mid 2000s, prostitution still takes place in walk-ups in parts of Soho, and there is drug dealing on some street corners.[36] By the end of 2014 gentrification had reduced the number of flats in Soho used for prostitution to around 40 but the area remains a red-light district[37] and a centre of the sex industry in London. There are a number of licensed sex shops, a clip joint on Tisbury Court and an adult cinema nearby. Prostitutes are available, operating in studio flats, often sign-posted by fluorescent "model" signs at street level.

Other

The National Hospital for Diseases of the Heart and Paralysis was established at No. 32 Soho Square in 1874. The property had previously been owned by the naturalist and botanist Sir Joseph Banks. It moved to Westmoreland Street in 1914, and then to Fulham Road in 1991.[38]

Streets

Berwick Street has record shops, fabric shops, and a small street market open from Monday to Saturday.

Carnaby Street was for a short time the fashion centre of 1960s "Swinging London" although it quickly became known for poor quality 'kitsch' products.

D'Arblay Street, formerly Portland Street, has The George public house, The Breakfast Club Cafe and a Pop up shop which recently held an art exhibition for the Mourlot Studios by King and McGaw.

Dean Street is home to the Soho Theatre, and a pub known as The French House which during World War II was popular with the French Government-in-exile. Karl Marx lived at numbers 54 and 28 Dean Street between 1851 and 1856. From 1948 to 2008 it was also the location of The Colony Club hosted by Muriel Belcher and frequented by Francis Bacon, Lucian Freud, George Melly and later Damien Hirst.

Frith Street where John Logie Baird first demonstrated television in his laboratory, now the location of Bar Italia. A plaque above the stage door of the Prince Edward Theatre identifies the site where Mozart lived for a few years as a child. Ronnie Scott's Jazz Club is located at 47 Frith Street having moved there from Gerrard Street in 1965.

Greek Street was first laid out around 1680 and was named after a nearby Greek church. It initially housed several upper-class tenants including Arthur Annesley, 5th Earl of Anglesey and Peter Plunket, 4th Earl of Fingall. Thomas De Quincey lived in the street after running away from Manchester Grammar School in 1982. Josiah Wedgwood ran his main pottery warehouse and showrooms at Nos. 12-13 between 1774 to 1797. The street now mostly contains restaurants, and several historical buildings from the early-18th century are still standing.[39]

Gerrard Street was built between 1677-85 on land owned by Charles Gerard, 1st Earl of Macclesfield called the Military Ground. The initial development contained a large house belonging to the Earl of Devonshire, which was subsequently occupied by Charles Montagu, 4th Earl of Manchester, Baron Wharton and Richard Lumley, 1st Earl of Scarbrough. Several foreign restaurants had become established on Gerrard Street by the end of the 19th century, including the Hotel des Etrangers and the Mont Blanc. In the 20th century, it became the centre of London's Chinatown.[40] Ronnie Scott's Jazz Club opened at 39 Gerrard Street in 1959 and remained there until its move to 47 Frith Street in 1965. Scott kept 39 Gerrard Street open for up and coming British Jazz musicians (referred to as 'the Old Place') until the lease ran out in 1967. The 43 Club was also on Gerrard Street.

Golden Square is a garden square which is now home to several major media companies.

Great Marlborough Street was first laid out in the early 18th century, and named after the military commander John Churchill, 1st Duke of Marlborough. The street was initially fashionable, and was home to numerous peers.[41] The London College of Music were based at No. 47 from 1896 to 1990.[41], while the department store Liberty is on the corner with Regent Street.[42] The street was the location of Philip Morris's original London factory and gave its name to the Marlboro brand of cigarettes.[43] Marlborough Street Magistrates Court was based at No. 20–21 and became one of the country's most important magistrates courts by the late 19th century.[41] The Marquess of Queensbury's libel trial against Oscar Wilde took place here in 1895. The Rolling Stones' Mick Jagger and Keith Richards were tried for drugs possession at the court in 1967, with fellow band member Brian Jones being similarly charged a year later.[44]

Great Windmill Street[note 1] was home to the Windmill Theatre which used to claim, slightly inaccurately, that "we never closed" during the war; it was finally sold and reconstructed as a cinema in 1964. The principles of The Communist Manifesto were laid out at a meeting in the Red Lion pub.

Old Compton Street is named after the Bishop of London Henry Compton and was first laid out in the 1670s, becoming fully developed by 1683. During the late 18th and 19th century, it became a popular meeting place for French exiles. The street was the birthplace of Europe's rock club circuit (2i's club)[45] and boasted the first adult cinema in England (The Compton Cinema Club). Dougie Millings, who was the famous tailor for The Beatles, had his first shop at 63 Old Compton Street which opened in 1962.[46] Old Compton Street is now the core of London's main gay village where there are several businesses catering for the gay community.[47]

In Soho Square are Paul McCartney's office MPL Communications, and the former Football Association headquarters.

Wardour Street was home of the Marquee Club. Another seventies rock hangout was The Intrepid Fox pub (at 97/99 Wardour Street), originally dedicated to Charles James Fox (who is featured on a relief on the outside of the building), and more recently a goth pub where customers wearing ties would be denied service, as being improperly dressed.

Transport

The nearest London Underground stations are Oxford Circus, Piccadilly Circus, Tottenham Court Road, Leicester Square and Covent Garden.

Westminster Council stated that the narrow footways can become very congested at night, particularly at weekends, with people drinking in the street, eating outside takeaways, queuing at entertainment venues or to use bank ATMs, and people passing through the area. There are a number of premises with tables and chairs located on restricted pavement areas and this can cause non-violent traffic/pedestrian conflict.

See also

Notes

- ↑ Great Windmill Street (not indicated on this map, but located below Lexington Street)

References

Citations

- ↑ 'Estate and Parish History', Survey of London: volumes 33 and 34: St Anne Soho (1966), pp. 20–6 accessed: 17 May 2007

- ↑ Room 1983, p. 113.

- ↑ Mee 2014, p. 233.

- ↑ White, Norval; Willensky, Elliot & Leadon, Fran (2010), AIA Guide to New York City (5th ed.), New York: Oxford University Press, ISBN 9780195383867, p.111

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Weinreb et al 2008, p. 845.

- 1 2 3 Sheppard, F H W, ed. (1996). "Estate and Parish History". Survey of London. London. 33–34 : St Anne Soho: 20–26. Retrieved 10 April 2017.

- 1 2 3 Weinreb et al 2008, p. 846.

- ↑ F H W Sheppard, ed. (1966). "Map of the Parish of St. Anne, Soho" (Map). Survey of London. London. 33-34: St Anne Soho. Retrieved 3 July 2017.

- 1 2 Weinreb et al 2008, p. 847.

- ↑ Making the Modern World — John Snow and the Broad Street pump

- ↑ Johnson 2006, p. 299.

- ↑ Johnson 2006, pp. 227–228.

- ↑ Henry Barton Baker (1899). Stories of the streets of London. Chapman and Hall Ltd. p. 229.

- ↑ Girling 2012, p. 104.

- ↑ Girling 2012, p. 106.

- ↑ Conte 2008, p. 208.

- ↑ Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde by Robert Louis Stevenson, 1886

- ↑ "On this day - 1999: Dozens injured in Soho nail bomb". BBC News. 30 April 2005. Retrieved 18 May 2017.

- ↑ Weinreb et al 2008, pp. 1027-1028.

- ↑ "The Windmill Theatre, 17 – 19 Great Windmill Street, W.1". Arthurlloyd.co.uk. February 2003. Retrieved 5 August 2015.

- ↑ Weinreb et al 2008, p. 1028.

- ↑ "Ian Hamilton; The Comic Strip" (3 September 1981) London Review of Books

- ↑ Soho – The World's Creative Hub – BOP Consulting 2013

- ↑ "Launching tomorrow, Soho’s new radio station gives Sullivan the wag a place in its shop window". Shapers of the 80s. Wordpress. 6 May 2014. Retrieved 6 September 2014.

- ↑ "About". Soho Radio. Flatpak Radio. 2014. Retrieved 6 September 2014.

- ↑ "Tony Brainsby, Obituary", The Independent March 2000.

- ↑ "Why London's music scene has been rocked by the death of Denmark Street". The Guardian. 20 January 2015. Retrieved 18 May 2017.

- ↑ "London's Tin Pan Alley gets blue plaque". BBC News. 6 April 2014. Retrieved 29 June 2014.

- ↑ Smith, Andrew (4 August 2007). "Making tracks". The Guardian. Retrieved 26 June 2014.

- ↑ Girling 2012, p. 15.

- ↑ During 2009, pp. 110–111.

- ↑ Matthew Sweet "The lost worlds of British cinema: The horror", The Independent, 29 January 2006

- ↑ Hunt, Leon (2013). British Low Culture: From Safari Suits to Sexploitation. Routledge. p. 24. ISBN 9781136189364.

- ↑ Sinful Streets of London (map and guide book), published in 1983

- ↑ "Paul Raymond the King of Soho". Strip Magazine. 27 December 2013. Retrieved 15 June 2016.

- ↑ "Soho drug dealers jailed". Metropolitan Police Service. 19 Aug 2013. Retrieved 6 August 2015.

- ↑ "So long, Soho". The Economist. 30 December 2014.

- ↑ Girling 2012, p. 108.

- ↑ Weinreb et al 2008, p. 350.

- ↑ Weinreb et al 2008, p. 323.

- 1 2 3 Weinreb et al 2008, p. 342.

- ↑ Weinreb et al 2008, p. 343.

- ↑ Kluger, Richard (1997). Ashes to Ashes: America's Hundred-Year Cigarette War, the Public Health, and the Unabashed Triumph of Philip Morris. Vintage Books. p. 50. ISBN 0-375-70036-6.

- ↑ Moore 2003, pp. 145–6.

- ↑ Weinreb et al 2008, p. 599.

- ↑ Gorman 2001, p. 37.

- ↑ Weinreb et all 2008, p. 599.

Sources

- Conte, Joseph (2008). Flies in My Spaghetti, Chocolates Over the Wall. Tate Publishing. ISBN 978-1-604-62251-5.

- During, Simon (30 June 2009). Modern Enchantments: The Cultural Power of Secular Magic. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-03439-6.

- Girling, Brian (2012). Soho & Theatreland Through Time. Amberley Publishing. ISBN 978-1-445-63091-5.

- Gorman, Paul (2001). The Look: Adventures in Pop & Rock Fashion. Sanctuary.

- Johnson, Steven (19 October 2006). The Ghost Map: The Story of London's Most Terrifying Epidemic—and How It Changed Science, Cities, and the Modern World. Penguin Publishing Group. ISBN 978-1-101-15853-1.

- Mee, Arthur (30 July 2014). King's England: London. Amberley Publishing Limited. ISBN 978-1-4456-4239-0.

- Moore, Tim (2003). Do Not Pass Go. Vintage. ISBN 978-0-099-43386-6.

- Room, Adrian (15 December 1983). A Concise Dictionary of Modern Place-names in Great Britain and Ireland. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-211590-4.

- Weinreb, Ben; Hibbert, Christopher; Keay, Julia; Keay, John (2008). The London Encyclopedia. Pan MacMillan. ISBN 978-1-4050-4924-5.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Soho. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for London/Soho. |

- The museum of Soho

- Soho memories

- The Soho Society

- The Survey of London: volumes 33 and 34, St Anne Soho (1966)—full text online

- The Soho Bombing in 1999

Coordinates: 51°30′46″N 0°7′52″W / 51.51278°N 0.13111°W

.jpg)