Snowmaking

Snowmaking is the production of snow by forcing water and pressurized air through a "snow gun," also known as a "snow cannon", on ski slopes. Snowmaking is mainly used at ski resorts to supplement natural snow. This allows ski resorts to improve the reliability of their snow cover and to extend their ski seasons from late autumn to early spring. Indoor ski slopes often use snowmaking. They can generally do so year-round as they have a climate-controlled environment.

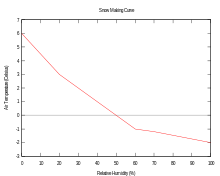

The production of snow requires low temperatures. The threshold temperature for snowmaking increases as humidity decreases. Wet bulb temperature is used as a metric since it takes air temperature and relative humidity into account. Snowmaking is a relatively expensive process in its energy use, thereby limiting its use.

History

Art Hunt, Dave Richey, and Wayne Pierce invented the snow cannon in 1950,[1][2] but secured a patent sometime later.[3] In 1952, Grossinger's Catskill Resort Hotel became the first in the world to use artificial snow.[4] Snowmaking began to be used extensively in the early 1970s. Many ski resorts depend heavily upon snowmaking.

Snowmaking has achieved greater efficiency with increasing complexity. Traditionally, snowmaking quality depended upon the skill of the equipment operator. Computer control supplements that skill with greater precision, such that a snow gun operates only when snowmaking is optimal. All-weather snowmakers have been developed by IDE.[5]

Operation

The key considerations in snow production are increasing water and energy efficiency and increasing the environmental window in which snow can be made.

Snowmaking plants require water pumps and sometimes air compressors when using lances, that are both very large and expensive. The energy required to make artificial snow is about 0.6 - 0.7 kW h/m³ for lances and 1 - 2 kW h/m³ for fan guns. The density of artificial snow is between 400 and 500 kg/m³ and the water consumption for producing snow is roughly equal to that number.[6]

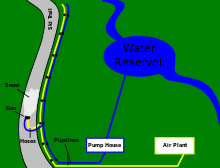

Snowmaking begins with a water supply such as a river or reservoir. Water is pushed up a pipeline on the mountain using very large electric pumps in a pump house. This water is distributed through an intricate series of valves and pipes to any trails that require snowmaking. Many resorts also add a nucleating agent to ensure that as much water as possible freezes and turns into snow. These products are organic or inorganic materials that facilitate the water molecules to form the proper shape to freeze into ice crystals. The products are non-toxic and biodegradable.

The next step in the snowmaking process is to add air using an air plant. This plant is often a building which contains electric or diesel industrial air compressors the size of a van or truck. However, in some instances air compression is provided using diesel-powered, portable trailer-mounted compressors which can be added to the system. Many fan-type snow guns have on-board electric air compressors, which allows for cheaper, and more compact operation. A ski area may have the required high-output water pumps, but not an air pump. Onboard compressors are cheaper and easier than having a dedicated pumping house. The air is generally cooled and excess moisture is removed before it is sent out of the plant. Some systems even cool the water before it enters the system. This improves the snowmaking process as the less heat in the air and water, the less heat must be dissipated to the atmosphere to freeze the water. From this plant the air travels up a separate pipeline following the same path as the water pipeline.

Ice nucleation-active proteins

The water is sometimes mixed with ina (ice nucleation-active) proteins from the bacterium Pseudomonas syringae. These proteins serve as effective nuclei to initiate the formation of ice crystals at relatively high temperatures, so that the droplets will turn into ice before falling to the ground. The bacterium itself uses these ina proteins in order to injure plants.[7]

Infrastructure

The pipes following the trails are equipped with shelters containing hydrants, electrical power and, optionally, communication lines mounted. Whereas shelters for fan guns require only water, power and maybe communication, lance-shelters usually need air hydrants as well. Hybrid shelters allow maximum flexibility to connect each snow machine type as they have all supplies available. The typical distance for lance shelters is 100–150 feet (30–46 m), for fan guns 250–300 feet (76–91 m). From these hydrants 1 1⁄2"–2" pressure resistant hoses are connected similar to fire hoses with camlocks to the snow machine.

Snowmaking guns

There are many forms of snowmaking guns; however, they all share the basic principle of combining air and water to form snow. For most guns the type or "quality" of snow can be changed by regulating the amount of water in the mixture. For others, the water and air are simply on or off and the snow quality is determined by the air temperature and humidity.

In general there are three types of snowmaking guns: Internal Mixing, External Mixing and Fan Guns. These come in two main styles of makers: air water guns and fan guns.

An air water gun can be mounted on a tower or on a stand on the ground. It uses higher pressure water and air, while a fan gun uses a powerful axial fan to propel the water jet to a great distance.

A modern snow fan usually consists of one or more rings of nozzles which inject water into the fan air stream. A separate nozzle or small group of nozzles is fed with a mix of water and compressed air and produces the nucleation points for the snow crystals. The small droplets of water and the tiny ice crystals are then mixed and propelled out by a powerful fan, after which they further cool through evaporation in the surrounding air as they fall to the ground. The crystals of ice act as seeds to make the water droplets freeze at 0 °C (32 °F). Without these crystals the water would supercool instead of freezing. This method can produce snow when the wet-bulb temperature of the air is as high as -1 °C (30.2 °F).[8][9] The lower the air temperature is, the more and the better snow a cannon can make. This is one of the main reasons snow cannons are usually operated in the night. The quality of the mixing of the water and air streams and their relative pressures is crucial to the amount of snow made and its quality.

Modern snow cannons are fully computerized and can operate autonomously or be remotely controlled from a central location. Operational parameters are: starting and stopping time, quality of snow, maximum wet-bulb temperature in which to operate, maximum windspeed, horizontal and vertical orientation, and sweep angle (to cover a wider or narrower area). Sweep angle and area may follow wind direction.

- Internal mixing guns have a chamber where the water and air are mixed together and forced through jets or through holes and fall to the ground as snow. These guns are typically low to the ground on a frame or tripod and require a lot of air to compensate for the short hang time (time the water is airborne). Some newer guns are built in a tower form and use much less air because of the increased hang time. The amount of water flow determines the type of snow that is to be made and is controlled by an adjustable water valve.

- External mixing guns have a nozzle spraying water as a stream and air nozzles shooting air through this water stream to break it up into much smaller water particles. These guns are sometimes equipped with a set of internal mixing nozzles that are known as nucleators. These help create a nucleus for the water droplets to bond to as they freeze. External mixing guns are typically tower guns and rely on a longer hang time to freeze the snow. This allows them to use much less air. External mixing guns are usually reliant on high water pressure to operate correctly so the water supply is opened completely, though in some the flow can be regulated by valves on the gun.

- Fan Guns are very different from all other guns because they require electricity to power a fan as well as an on-board reciprocating piston air compressor; modern fan guns do not require compressed air from an external source. Compressed air and water are shot out of the gun through a variety of nozzles (there are many different designs) and then the wind from the large fan blows this into a mist in the air to achieve a long hang time. Fan guns have anywhere from 12 to 360 water nozzles on a ring on the front of the gun through which the fan blows air. These banks can be controlled by valves. The valves are either manual, manual electric, or automatic electric (controlled by logic controller or computer).

- Snow Lances are up to 12 meter long vertically inclined aluminum tubes at the head of which are placed water and-or air nucleators. Air is blown into the atomized water at the outlet from the water nozzle. The previously compressed air expands and cools, creating ice nuclei on which crystallization of the atomized water takes place. Due to the height and the slow rate of descent there will be enough time for this process. This process uses less energy than a fan gun, but has a smaller range and lower snow quality; it also has greater sensitivity to wind. Advantages over fan gun are: lower investment (only cable system with air and water, central compressor station), much quieter, half the energy consumption for the same amount of snow, simpler maintenance due to lower wear and fewer moving parts, and regulation of snow making is possible in principle. The working pressure of snow lances is 20-60 bar. There are also small mobile systems for the home user that are operated by the garden connection (Home Snow).

Home snowmaking

Smaller versions of the snow machines found at ski resorts exist, scaled down to run off household size air and water supplies. Home snowmakers receive their water supply either from a garden hose or from a pressure washer, which makes more snow per hour. Plans also exist for do-it-yourself snowmaking machines made out of plumbing fittings and special nozzles.

Volumes of snow output by home snowmakers depend on the air/water mixture, temperature, wind variations, pumping capacity, water supply, air supply, and other factors. Using a household spray bottle will not work unless temperatures are well below the freezing point of water.

Other uses

In Swedish, the phrase "snow cannon" (Snökanon) is used to designate the Lake-effect snow weather phenomenon. For example, if the Baltic sea is not yet frozen in January, cold winds from Siberia may lead to significant snowfall.

Gallery

A snow making machine at Smiggin Holes, New South Wales, Australia

A snow making machine at Smiggin Holes, New South Wales, Australia- Full blast snow cannon at The Nordic Centre, Canmore, Alberta, Canada

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Snow cannon. |

- Artificial ski slopes

- Snow grooming

- Kern arc - one of optical displays caused by snowgun ice crystal clouds

- Pumpable ice technology

References

- ↑ Selingo, Jeffrey (2001-02-02). "Machines Let Resorts Please Skiers When Nature Won't". New York Times. Retrieved 2010-05-23.

- ↑ "Making Snow". About.com. Retrieved 2006-12-16.

- ↑ US patent 2676471, W. M. Pierce, Jr., "Method for Making and Distributing Snow", issued 1950-12-14

- ↑ On This Day: March 25, BBC News, accessed December 20, 2006. "The first artificial snow was made two years later, in 1952, at Grossinger's resort in New York, USA. "

- ↑ http://www.ide-snowmaker.com/

- ↑ Jörgen Rogstam & Mattias Dahlberg (April 1, 2011), Energy usage for snowmaking (PDF)

- ↑ Robbins, Jim (May 24, 2010), "From Trees and Grass, Bacteria That Cause Snow and Rain", The New York Times

- ↑ Liu, Xiaohong (2012). "What processes control ice nucleation and its impact on ice-containing clouds?" (PDF). Pacific Northwest National Library. Retrieved 2016-11-23.

- ↑ Kim, H. K. (1987-07-07). "Xanthomonas campestris pv. translucens Strains Active in Ice Nucleation" (PDF). The American Phytopathological Society. Retrieved 2016-11-23.