Snoring

| Snoring | |

|---|---|

| Sound sample of snoring | |

| Classification and external resources | |

| Specialty | Otorhinolaryngology, sleep medicine |

| ICD-10 | R06.5 |

| ICD-9-CM | 786.09 |

| DiseasesDB | 12260 |

| MedlinePlus | 003207 |

| Patient UK | Snoring |

| MeSH | D012913 |

Snoring is the vibration of respiratory structures and the resulting sound due to obstructed air movement during breathing while sleeping. In some cases, the sound may be soft, but in most cases, it can be loud and unpleasant. Snoring during sleep may be a sign, or first alarm, of obstructive sleep apnea (OSA). Research suggests that snoring is one of the factors of sleep deprivation.

Signs and symptoms

Snoring is known to cause sleep deprivation to snorers and those around them, as well as daytime drowsiness, irritability, lack of focus and decreased libido.[1] It has also been suggested that it can cause significant psychological and social damage to sufferers.[2] Multiple studies reveal a positive correlation between loud snoring and risk of heart attack (about +34% chance) and stroke (about +67% chance).[3]

Though snoring is often considered a minor affliction, snorers can sometimes suffer severe impairment of lifestyle. The between-subjects trial by Armstrong et al. discovered a statistically significant improvement in marital relations after snoring was surgically corrected. This was confirmed by evidence from Gall et al.,[4] Cartwright and Knight[5] and Fitzpatrick et al.[6]

New studies associate loud "snoring" with the development of carotid artery atherosclerosis.[7] Amatoury et al.[8] demonstrated that snoring vibrations are transmitted to the carotid artery, identifying a possible mechanism for snoring-associated carotid artery damage and atherosclerotic plaque development. These researchers also found amplification of the snoring energy within the carotid lumen at certain frequencies, adding to this scenario. Vibration of the carotid artery with snoring also lends itself as a potential mechanism for atherosclerotic plaque rupture and consequently ischemic stroke.[8] Researchers also hypothesize that loud snoring could create turbulence in carotid artery blood flow.[9] Generally speaking, increased turbulence irritates blood cells and has previously been implicated as a cause of atherosclerosis. While there is plausibility and initial evidence to support snoring as an independent source of carotid artery/cardiovascular disease, additional research is required to further clarify this hypothesis.[10]

A U.S. study estimates that roughly one in every 15 Americans is affected by at least a moderate degree of sleep apnea.[11]

Causes

In Layman's terms, snoring is the result of the relaxation of the uvula and soft palate.[12] These tissues can relax enough to partially block the airway, resulting in irregular airflow and vibrations.[13] Snoring can be attributed to one or more of the following:

- Throat weakness, causing the throat to close during sleep.[14]

- Mispositioned jaw, often caused by tension in the muscles.[13]

- Obesity that has caused fat to gather in and around the throat.[14]

- Obstruction in the nasal passageway.[13]

- Obstructive sleep apnea.[13]

- Sleep deprivation.[13]

- Relaxants such as alcohol or other drugs relaxing throat muscles.[13]

- Sleeping on one's back, which may result in the tongue dropping to the back of the mouth.[13]

Treatment

So far, there is no certain treatment that can completely stop snoring. Almost all treatments for snoring revolve around lessening the breathing discomfort by clearing the blockage in the air passage. Medications are usually not helpful in treating snoring symptoms, though they can help control some of the underlying causes such as nasal congestion and allergic reactions. Doctors, therefore, often recommend lifestyle changes as a first line treatment to stop snoring.[15] This is the reason snorers are advised to lose weight[16] (to stop fat from pressing on the throat), stop smoking (smoking weakens and clogs the throat), avoid alcohol and sedative medications before bedtime (they relax the throat and tongue muscles, which in turn narrow the airways)[17] and sleep on their side (to prevent the tongue from blocking the throat).[18]

A number of other treatment options are also used to stop snoring. These range from over-the-counter aids such as nasal sprays, nasal strips or nose clips, lubricating sprays, oral appliances and "anti-snore" clothing and pillows, to unusual activities such as playing the didgeridoo.[19] However, one needs to be wary of over-the-counter snore treatments that have no scientific evidence to support their claims, such as stop-snore rings or wrist worn electrical stimulation bands.

Orthopedic pillows

Orthopedic pillows are the least intrusive option for reducing snoring. These pillows are designed to support the head and neck in a way that ensures the jaw stays open and slightly forward. This helps keep the airways unrestricted as possible and in turn leads to a small reduction in snoring.[20]

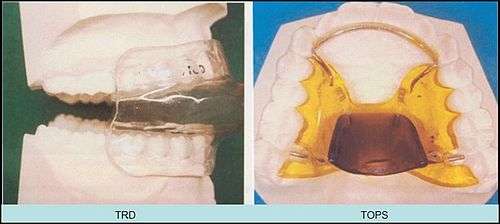

Dental appliances

Specially made dental appliances called mandibular advancement splints, which advance the lower jaw slightly and thereby pull the tongue forward, are a common mode of treatment for snoring. Such appliances have been proven to be effective in reducing snoring and sleep apnea in cases where the apnea is mild to moderate.[21] Mandibular advancement splints are often tolerated much better than CPAP machines.[22]

Positive airway pressure

A continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) machine is often used to control sleep apnea and the snoring associated with it. It is a relatively safe medical treatment. To keep the airway open, a device pumps a controlled stream of air through a flexible hose to a mask worn over the nose, mouth, or both.[23] A CPAP is usually applied through a CPAP mask which is placed over the nose and/or mouth. The air pressure required to keep the airway open is delivered through this and it is attached to a CPAP machine which is like an air compressor.

The air that CPAP delivers is generally "normal air" – not concentrated oxygen. The machine utilizes the air pressure as an "air splint" to keep the airway open. In obstructive sleep apnea, the airway at the rear of the throat is prone to closure.

Surgery

Surgery is also available as a method of correcting social snoring. Some procedures, such as uvulopalatopharyngoplasty, attempt to widen the airway by removing tissues in the back of the throat, including the uvula and pharynx. These surgeries are quite invasive, however, and there are risks of adverse side effects. The most dangerous risk is that enough scar tissue could form within the throat as a result of the incisions to make the airway more narrow than it was prior to surgery, diminishing the airspace in the velopharynx. Scarring is an individual trait, so it is difficult for a surgeon to predict how much a person might be predisposed to scarring. Currently, the American Medical Association does not approve of the use of lasers to perform operations on the pharynx or uvula.

Radiofrequency ablation (RFA) is a relatively new surgical treatment for snoring. This treatment applies radiofrequency energy and heat (between 77 °C and 85 °C) to the soft tissue at the back of the throat, such as the soft palate and uvula, causing scarring of the tissue beneath the skin. After healing, this results in stiffening of the treated area. The procedure takes less than one hour, is usually performed on an outpatient basis, and usually requires several treatment sessions. Radiofrequency ablation is frequently effective in reducing the severity of snoring, but often does not completely eliminate it.[24][25]

Bipolar radiofrequency ablation, a technique used for coblation tonsillectomy, is also used for the treatment of snoring.

Pillar procedure

The Pillar Procedure is a minimally invasive treatment for snoring and obstructive sleep apnea. In the United States, this procedure was FDA indicated in 2004. During this procedure, three to six+ dacron (the material used in permanent sutures) strips are inserted into the soft palate, using a modified syringe and local anesthetic. While the procedure was initially approved for the insertion of three "pillars" into the soft palate, it was found that there was a significant dosage response to more pillars, with appropriate candidates. As a result of this outpatient operation, which typically lasts no more than 30 minutes, the soft palate is more rigid, possibly reducing instances of sleep apnea and snoring. This procedure addresses one of the most common causes of snoring and sleep apnea — vibration or collapse of the soft palate (the soft part of the roof of the mouth). If there are other factors contributing to snoring or sleep apnea, such as conditions of the nasal airway or an enlarged tongue, it will likely need to be combined with other treatments to be more effective.[26]

Medication

An open label non-randomized study in 30 patients found benefit from pseudoephedrine, domperidone, and the combination in the treatment of severe snoring.[27]

Alternative medicine

Among the natural remedies are exercises to increase the muscle tone of the upper airway,[28] and one medical practitioner noting anecdotally that professional singers seldom snore,[29] but there have been no medical studies to fully link the two.[30]

Epidemiology

Statistics on snoring are often contradictory, but at least 30% of adults and perhaps as many as 50% of people in some demographics snore.[31] One survey of 5,713 American residents identified habitual snoring in 24% of men and 13.8% of women, rising to 60% of men and 40% of women aged 60 to 65 years; this suggests an increased susceptibility to snoring as age increases.[32]

See also

References

- ↑ Luboshitzky, Rafael; Ariel Aviv; Aya Hefetz; Paula Herer; Zila Shen-Orr; Lena Lavie; Peretz Lavie (March 23, 2002). "Decreased Pituitary-Gonadal Secreti". Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 87 (7): 3394–3398. PMID 12107256. doi:10.1210/jc.87.7.3394. Retrieved 2007-07-03.

Decreased libido is frequently reported in male patients with obstructive sleep apnea (OSA).

- ↑ "The effect of surgery upon the quality of life in snoring patients and their partners: a between-subjects case-controlled trial". M.W.J. Armstrong, C.L. Wallace & J. Marais, Clinical Otolaryngology & Allied Sciences 24 6 Page 510. 1999-01-12.

- ↑ "Snoring 'linked to heart disease'". BBC News. 2008-03-01. Retrieved 2010-05-23.

- ↑ "Quality of life in mild obstructive sleep apnea". Gall, R., Isaac, L., Kryger, M. (1993) Sleep, 16, S59 S61. 1993.

- ↑ "Silent partners: the wives of sleep apneic patients". Cartwright, R.D. & Knight, S. (1987) Sleep, 10, 244 248. 1987.

- ↑ "Snoring, asthma and sleep disturbance in Britain: a community-based survey". Fitzpatrick, M.F., Martin, K., Fossey, E et al. (1993) Eur. Respir. J. 69, 531 535. 1993.

- ↑ Lee, SA; TC Amis; K Byth; G Larcos; K Kairaitis; TD Robinson; JR Wheatley (September 2008). "Heavy snoring as a cause of carotid artery atherosclerosis". Sleep. Associated Professional Sleep Societies. 31 (9): 1207–1213. ISSN 0161-8105. PMC 2542975

. PMID 18788645.

. PMID 18788645. - 1 2 Amatoury, J; Howitt, L; Wheatley, JR; Avolio, AP; Amis, TC (May 2006). "Snoring-related energy transmission to the carotid artery in rabbits.". Journal of applied physiology (Bethesda, Md. : 1985). 100 (5): 1547–53. PMID 16455812. doi:10.1152/japplphysiol.01439.2005.

- ↑ "Snoring: A Precursor to Medical Issues" (PDF). Stop Snoring Device. Retrieved 28 June 2016.

- ↑ Amatoury, Jason. "Health Check: is snoring anything to worry about?". The Conversation. Retrieved 15 March 2017.

- ↑ "That Statistics of Sleep Apnea". Sleep Disorders Guide. Retrieved 28 June 2016.

- ↑ Chokroverty, Sudhansu (2007). 100 Questions & Answers About Sleep And Sleep Disorders. Jones & Bartlett Learning. p. 124. ISBN 0763741205.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "Snoring Causes". Mayo Clinic. Mayo Clinic. 26 April 2015. Retrieved 15 June 2016.

- 1 2 "Obstructive sleep apnea". University of Maryland. University of Maryland Medical Center. 19 September 2012. Retrieved 15 June 2016.

- ↑ "How to Stop Snoring: Causes, Cures, and Remedies". Medical-Reference. Retrieved 26 September 2016.

- ↑ "Snoring - Facts and myths". American Sleep Association. Retrieved 25 July 2016.

- ↑ "Obstructive sleep apnea: Overview". U.S. National Library of Medicine — Pubmed Health. Retrieved 26 September 2016.

- ↑ "How To Stop Snoring". The Dozy Owl. Retrieved 8 September 2016.

- ↑ "Didgeridoo playing as alternative treatment for obstructive sleep apnea syndrome". British Medical Journal. 2005-12-23.

- ↑ "Anti-Snoring Pillows: Can They Help With Snoring?". Retrieved 2016-01-20.

- ↑ , Henke,Frantz AM J RESPIR CRIT CARE MED 2000;161:420–425.

- ↑ "Comparative Study of Oral Devices for Snoring" , Journal of the California Assoc. Aug. 1998

- ↑ "Continuous Positive Airway Pressure (CPAP)". American Academy of Otolaryngology−Head and Neck Surgery. Retrieved 2007-07-02.

- ↑ Snoring subdued with new treatment: 5/20/98

- ↑ Radiofrequency ablation of the soft palate for snoring

- ↑ "What is pillar". Pillar Procedure. Retrieved 29 September 2016.

- ↑ "Treatment of Severe Snoring with a Combination of Pseudoephedrine Sulfate and Domperidone." (PDF). Retrieved 2012-05-01.

- ↑ Pai, Irumee; Lo, Stephen; Wolf, Dennis; ajieker, Azgher (2008). "The effect of singing on snoring and daytime somnolence". Sleep and Breathing. 12 (3): 265–268. PMID 18183444. doi:10.1007/s11325-007-0159-1. Retrieved 9 January 2011

- ↑ Scott, Elizabeth (1995). The Natural Way to Stop Snoring. London: Orion Books. ISBN 0-7528-0067-1

- ↑ Valbuza, J.S; de Oliveira, M.M; Conti, C.F; Prado, L.B.F; de Carvalho, L.B.C; do Prado, G.F (2008). "Methods to increase muscle tonus of upper airway to treat snoring: Systematic review" (PDF). Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 66 (3-B): 773–776. doi:10.1590/s0004-282x2008000500037. Retrieved 9 January 2011

- ↑ "New Vaccine Could Cure Snoring (statistics insert)". BBC News. 2001-09-19.

- ↑ "Some epidemiological data on snoring and cardiocirculatory disturbances". Lugaresi E., Cirignotta F., Coccoagna G. et al. (1980), Sleep 3, 221–224.