Small carbonaceous fossil

Small carbonaceous fossils (SCFs) are sub-millimetric organic remains of organisms preserved in sedimentary strata.

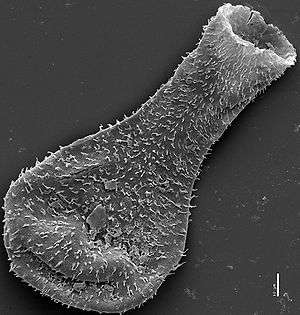

The category of fossils includes robust or thick-walled entities such as plant spores, acritarchs and chitinozoa, but the most interesting components are fragile remnants of animals that can only be extracted through a delicate maceration technique.[1] SCFs are relatively widespread and abundant, and can potentially preserve both mineralized and non-mineralized parts of organisms. This undertapped record of the evolutionary processes occurring in the Palaeozoic cirtcumvents the biases inherent in the shelly fossil record.[1]

Extraction

SCFs are typically preserved in fine-grained siliciclastic rocks, and are too small to be fruitfully examined on bedding planes. Instead, they are extracted by dissolving the rock in acid. Traditional palynological preparations involve high-energy steps such as centrifuging that destroy large and fragile fossils. In the more delicate technique pioneered by Butterfield,[2] individual microfossils are picked from sieved acid residues by hand. The sieving stage removes crystalline residue, making it easier to extract fossils, but introduces a filter: the smallest fossils (<~40 µm) pass through the sieve and are lost.[1] Once extracted, fossils can be mounted for light or scanning electron microscopy: transmitted light illuminates internal microstructures, whereas SEM picks out surface features.

Preservation

SCFs are best preserved in anoxic conditions with limited thermal maturity; the presence of oxygen is particularly deleterious at high temperatures.[3]

Biota

Traditional palynological methods tend to extract plant spores and resistant microfossils such as acritarchs and chitinozoa. The delicate approach can also recover fragments of animals: scales from priapulid worms, Wiwaxia sclerites, and arthropod feeding parts, for example. These organisms are not represented in the conventional (shelly) fossil record, so the SCF record provides data on their distribution and evolution that would not otherwise be available. Lagerstatten such as the Burgess Shale provide isolated snapshots of Palaeozoic life, whereas the SCF record provides a more continuous record, albeit blighted by the fragmentary (and consequently enigmatic) nature of many of its constituents.[1] As such, the SCFs can fill in the details of the fossil record: for instance, highlighting the rapid nature of the Cambrian explosion.[4]

References

- 1 2 3 4 Butterfield, N. J.; Harvey, T. H. P. (2011). "Small carbonaceous fossils (SCFs): A new measure of early Paleozoic paleobiology". Geology. 40: 71. doi:10.1130/G32580.1.

- ↑ Butterfield, N. J. (1990). "A reassessment of the enigmatic Burgess Shale fossil Wiwaxia corrugata (Matthew) and its relationship to the polychaete Canadia spinosa Walcott". Paleobiology. 16 (3): 287–303. JSTOR 2400789. doi:10.2307/2400789.

- ↑ Schiffbauer, J. D.; Wallace, A. F.; Hunter, J. L.; Kowalewski, M.; Bodnar, R. J.; Xiao, S. (2012). "Thermally-induced structural and chemical alteration of organic-walled microfossils: An experimental approach to understanding fossil preservation in metasediments". Geobiology. 10 (5): 402–423. PMID 22607551. doi:10.1111/j.1472-4669.2012.00332.x.

- ↑ Harvey, T. H. P.; Velez, M. I.; Butterfield, N. J. (2012). "Exceptionally preserved crustaceans from western Canada reveal a cryptic Cambrian radiation". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 109 (5): 1589. PMC 3277126

. PMID 22307616. doi:10.1073/pnas.1115244109.

. PMID 22307616. doi:10.1073/pnas.1115244109.