Meerkat

| Meerkat | |

|---|---|

_Tswalu.jpg) | |

| A mob of meerkats at the Tswalu Kalahari Reserve in South Africa. | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Carnivora |

| Family: | Herpestidae |

| Genus: | Suricata Desmarest, 1804 |

| Species: | S. suricatta |

| Binomial name | |

| Suricata suricatta (Schreber, 1776) | |

| |

| Meerkat range | |

The meerkat or suricate (Suricata suricatta) is a small carnivoran belonging to the mongoose family (Herpestidae). It is the only member of the genus Suricata.[2] Meerkats live in all parts of the Kalahari Desert in Botswana, in much of the Namib Desert in Namibia and southwestern Angola, and in South Africa. A group of meerkats is called a "mob", "gang" or "clan". A meerkat clan often contains about 20 meerkats, but some super-families have 50 or more members. In captivity, meerkats have an average life span of 12–14 years, and about half this in the wild.

Etymology

"Meerkat" is a loanword from Afrikaans (pronounced [ˈmɪərkat]).[3] The name has a Dutch origin, but by misidentification. In Dutch, meerkat means the guenon, a monkey of the Cercopithecus genus.[4] The word meerkat is Dutch for "lake cat", but although the suricata is a feliform, it is not of the cat family;[5] the word possibly started as a Dutch adaptation of a derivative of Sanskrit markaṭa मर्कट = "ape",[6] perhaps in Africa via an Indian sailor on board a Dutch East India Company ship.[7]

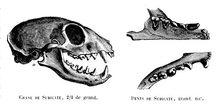

Anatomy

The meerkat is a small diurnal herpestid (mongoose)[8] weighing on average about 0.5 to 2.5 kilograms (1.1 to 5.5 lb).[9][10] Its long slender body and limbs give it a body length of 35 to 50 centimetres (14 to 20 in) and an added tail length of around 25 centimetres (9.8 in).[11] The meerkat uses its tail to balance when standing upright, as well as for signaling.[12] Its face tapers, coming to a point at the nose, which is brown. The eyes always have black patches around them, and they have small black crescent-shaped ears.[13] Like cats, meerkats have binocular vision, their eyes being on the front of their faces.[14]

At the end of each of a meerkat's "fingers" is a claw used for digging burrows and digging for prey.[11] Claws are also used with muscular hindlegs to help climb trees. Meerkats have four toes on each foot and long slender limbs. The coat is usually peppered gray, tan, or brown with silver.[13] They have short parallel stripes across their backs, extending from the base of the tail to the shoulders.[12] The patterns of stripes are unique to each meerkat. The underside of the meerkat has no markings, but the belly has a patch which is only sparsely covered with hair and shows the black skin underneath. The meerkat uses this area to absorb heat while standing on its rear legs, usually early in the morning after cold desert nights.[15]

Diet and foraging behaviour

_digging.jpg)

Meerkats are primarily insectivores, but also eat other animals (lizards, snakes, scorpions, spiders, eggs, small mammals, millipedes, centipedes and, more rarely, small birds), plants and fungi (the desert truffle Kalaharituber pfeilii[16]). Meerkats are immune to certain types of venom, including the very strong venom of the scorpions of the Kalahari Desert.[17]

Baby meerkats do not start foraging for food until they are about 1 month old, and do so by following an older member of the group who acts as the pup's tutor.[18] Meerkats forage in a group with one "sentry" on guard watching for predators while the others search for food. Sentry duty is usually approximately an hour long. The meerkat standing guard makes peeping sounds when all is well.[19]

A meerkat has the ability to dig through a quantity of sand equal to its own weight in just seconds.[20] Digging is done to create burrows, to get food and also to create dust clouds to distract predators.[21]

Predators

Martial eagles, tawny eagles and jackals are the main predators of meerkats.[22] Meerkats sometimes die of snakebite in confrontations with snakes (puff adders and Cape cobras).[23]

Reproduction

Meerkats become sexually mature at about two years of age and can have one to four pups in a litter, with three pups being the most common litter size. Meerkats are iteroparous and can reproduce any time of the year.[13] The pups are allowed to leave the burrow at two to three weeks old.[24]

There is no precopulatory display; the male may fight with the female until she submits to him and copulation begins. Gestation lasts approximately 11 weeks and the young are born within the underground burrow and are altricial (undeveloped). The young's ears open at about 10 days of age, and their eyes at 10–14 days. They are weaned around 49 to 63 days.[13]

Usually, the alpha pair reserves the right to mate and normally kills any young not its own, to ensure that its offspring have the best chance of survival. The dominant couple may also evict, or kick out the mothers of the offending offspring.[25] New meerkat groups are often formed by evicted females joining a group of males.[26]

Females appear to be able to discriminate the odour of their kin from the odour of their non-kin.[27] Kin recognition is a useful ability that facilitates cooperation among relatives and the avoidance of inbreeding. When mating does occur between meerkat relatives, it often results in negative fitness consequences or inbreeding depression. Inbreeding depression was evident for a variety of traits: pup mass at emergence from the natal burrow, hind-foot length, growth until independence and juvenile survival.[28] These negative effects are likely due to the increased homozygosity that arises from inbreeding and the consequent expression of deleterious recessive mutations. The avoidance of inbreeding and the promotion of outcrossing allow the masking of deleterious recessive mutations.[29] (Also see Complementation (genetics).)

Behavior

Meerkats are small burrowing animals, living in large underground networks with multiple entrances which they leave only during the day, except to avoid the heat of the afternoon.[30] They are very social, living in colonies.[13] Animals in the same group groom each other regularly.[19] The alpha pair often scent-mark subordinates of the group to express their authority.[31] There may be up to 30 meerkats in a group.[13]

To look out for predators, one or more meerkats stand sentry, to warn others of approaching dangers.[32] When a predator is spotted, the meerkat performing as sentry gives a warning bark or whistle, and other members of the group will run and hide in one of the many holes they have spread across their territory.[33]

Meerkats also babysit the young in the group. Females that have never produced offspring of their own often lactate to feed the alpha pair's young.[13] They also protect the young from threats, often endangering their own lives. On warning of danger, the babysitter takes the young underground to safety and is prepared to defend them if the danger follows.[34]

Meerkats are also known to share their burrow with the yellow mongoose and ground squirrel.[34]

Like many species, meerkat young learn by observing and mimicking adult behaviour, though adults also engage in active instruction. For example, meerkat adults teach their pups how to eat a venomous scorpion: they will remove the stinger and help the pup learn how to handle the creature.[35]

Despite this altruistic behaviour, meerkats sometimes kill young members of their group. Subordinate meerkats have been seen killing the offspring of more senior members in order to improve their own offspring's position.[36]

Vocalization

Meerkat calls may carry specific meanings, with particular calls indicating the type of predator and the urgency of the situation. In addition to alarm calls, meerkats also make panic calls, recruitment calls, and moving calls. They chirrup, trill, growl, or bark, depending on the circumstances.[37] Meerkats make different alarm calls depending upon whether they see an aerial or a terrestrial predator. Moreover, acoustic characteristics of the call will change with the urgency of the potential predatory episode. Therefore, six different predatory alarm calls with six different meanings have been identified: aerial predator with low, medium, and high urgency; and terrestrial predator with low, medium, and high urgency. Meerkats respond differently after hearing a terrestrial predator alarm call than after hearing an aerial predator alarm call. For example, upon hearing a high-urgency terrestrial predator alarm call, meerkats are most likely to seek shelter and scan the area. On the other hand, upon hearing a high-urgency aerial predator alarm call, meerkats are most likely to crouch down. On many occasions under these circumstances, they also look towards the sky.[38]

Subspecies

There are three subspecies of meerkat:[2]

- Southern African meerkat (Suricata suricatta suricatta), native to southern Namibia and Botswana, and South Africa.

- Angolan meerkat (Suricata suricatta iona), native to southwestern Angola.

- Desert meerkat (Suricata suricatta majoriae), native to the Namib desert and central and northwestern Namibia.

Domestication

Meerkats, as wild animals, make poor pets. They can be aggressive especially toward guests and may bite. They will scent-mark their owner and the house (their "territory").[39][40]

Popular culture

- Meerkat Manor, a British television program.

- The advertising campaign, Compare the Meerkat, is popular in the UK and Australia.

- Timon from The Lion King franchise is a meerkat.

- In the book Life of Pi and its film adaptation, the floating island is inhabited by tens of thousands of meerkats, in an environment and grouping unlike real meerkats.

- Billy from the film Animals United is a meerkat.

See also

- Kalahari Meerkat Project, a long-term research project

- The Meerkats, a 2008 documentary feature film

References

- ↑ Jordan, N. R.; Do Linh San, E. (2015). "Suricata suricatta". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. IUCN. 2015: e.T41624A45209377. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2015-4.RLTS.T41624A45209377.en. Retrieved 28 March 2017.

- 1 2 Wozencraft, W.C. (2005). "Genus Suricata". In Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M. Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 571. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- ↑ Durkin, Philip (2014). Borrowed Words: A History of Loanwords in English. OUP Oxford. p. 359. ISBN 978-0-19-166707-7.

- ↑ Aertsen, Henk; Jeffers, Robert J. (1993). Historical Linguistics 1989: Papers from the 9th International Conference on Historical Linguistics, New Brunswick, 14–18 August 1989. John Benjamins Publishing Company. p. 315. ISBN 978-90-272-7705-3.

- ↑ New International Encyclopedia. Dodd, Mead. 1916. p. 348.

- ↑ Harper, Douglas. "meerkat". Online Etymology Dictionary.

- ↑ Mitrani, Judith L. (2014). Psychoanalytic Technique and Theory: Taking the Transference. Karnac Books. p. 192. ISBN 978-1-78220-162-5.

- ↑ Feldhamer, George A.; Drickamer, Lee C.; Vessey, Stephen H.; Merritt, Joseph F.; Krajewski, Carey (2007). Mammalogy: Adaptation, Diversity, Ecology. JHU Press. p. 321. ISBN 978-0-8018-8695-9.

- ↑ Unwin, Mike (2011). Southern African Wildlife. Bradt Travel Guides. p. 55. ISBN 978-1-84162-347-4.

- ↑ Karlin, Adam (2010). Botswana & Namibia. Lonely Planet. p. 43. ISBN 978-1-74104-922-0.

- 1 2 Animals: A Visual Encyclopedia (Second Edition): A Visual Encyclopedia. DK Publishing. 2012. p. 83. ISBN 978-0-7566-9896-6.

- 1 2 Marshall Cavendish Reference (2010). Mammals of the Southern Hemisphere. Marshall Cavendish. p. 175. ISBN 978-0-7614-7937-6.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "Suricata suricatta". animaldiversity.org.

- ↑ Miller, Sara Swan (2007). All Kinds of Eyes. Marshall Cavendish. p. 37. ISBN 978-0-7614-2519-9.

- ↑ "Meerkat". theanimalfiles.com. Retrieved 5 January 2015.

- ↑ Trappe, James M.; Claridge, Andrew W.; Arora, David; Smit, W. Adriaan (2008). "Desert truffles of the Kalahari: ecology, ethnomycology and taxonomy". Economic Botany. 62 (3): 521–529. doi:10.1007/s12231-008-9027-6.

- ↑ David Attenborough's World Of Wildlife 9 – Meerkats United (1999). Video

- ↑ "Mighty Masked Meerkat Mobs". Lifeinthefastlane.ca. 7 December 2007. Archived from the original on 21 February 2008. Retrieved 19 November 2013.

- 1 2 Ciovacco, Justine (2008). Meerkats. Gareth Stevens Pub. pp. 28, 37 ff. ISBN 978-0-8368-9098-3.

- ↑ "LadyWildLife". LadyWildLife. 9 November 2012. Retrieved 24 May 2014.

- ↑ "LadyWildLife". LadyWildLife. 14 March 2016. Retrieved 24 May 2014.

- ↑ Kingdon, Jonathan; Happold, David; Butynski, Thomas; Hoffmann, Michael; Happold, Meredith; Kalina, Jan (2013). Mammals of Africa. A&C Black. p. 4. ISBN 978-1-4081-8996-2.

- ↑ Skyrms, Brian (2010). Signals: Evolution, Learning, and Information. Oxford University Press. p. 32. ISBN 978-0-19-161490-3.

- ↑ "Meerkat". zooatlanta.com. Retrieved 6 January 2015.

- ↑ Allman, Toney (2009). Animal Life in Groups. Infobase Publishing. p. 12. ISBN 978-1-4381-2606-7.

- ↑ Armitage, Kenneth B. (2014). Marmot Biology: Sociality, Individual Fitness, and Population Dynamics. Cambridge University Press. p. 351. ISBN 978-1-139-99300-5.

- ↑ Leclaire S, Nielsen JF, Thavarajah NK, Manser M, Clutton-Brock TH (2013). "Odour-based kin discrimination in the cooperatively breeding meerkat". Biol. Lett. 9 (1): 20121054. PMC 3565530

. PMID 23234867. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2012.1054.

. PMID 23234867. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2012.1054. - ↑ Nielsen JF, English S, Goodall-Copestake WP, Wang J, Walling CA, Bateman AW, Flower TP, Sutcliffe RL, Samson J, Thavarajah NK, Kruuk LE, Clutton-Brock TH, Pemberton JM (2012). "Inbreeding and inbreeding depression of early life traits in a cooperative mammal". Mol. Ecol. 21 (11): 2788–804. PMID 22497583. doi:10.1111/j.1365-294X.2012.05565.x.

- ↑ Bernstein H, Byerly HC, Hopf FA, Michod RE (1985). "Genetic damage, mutation, and the evolution of sex". Science. 229 (4719): 1277–81. PMID 3898363. doi:10.1126/science.3898363.

- ↑ Carnivores. Britannica Educational Publishing. 2010. p. 171. ISBN 978-1-61530-385-4.

- ↑ Martin, Vonne (2013). Southern Africa Safari. Author House. p. 47. ISBN 978-1-4817-1258-3.

- ↑ Kalat, James (2015). Biological Psychology. Cengage Learning. p. 113. ISBN 978-1-305-46529-9.

- ↑ Ganeri, Anita (2011). Meerkat. Heinemann Library. p. 19. ISBN 978-1-4329-4773-6.

- 1 2 Moore, Heidi (2004). A Mob of Meerkats. Heinemann Library. p. 15. ISBN 978-1-4034-4694-7.

- ↑ Thornton, Alex; McAuliffe, Katherine (2006). "Teaching in wild meerkats". Science. 313 (5784): 227–229. PMID 16840701. doi:10.1126/science.1128727.

- ↑ Norris, Scott (15 March 2006). "Murderous meerkat moms contradict caring image, study finds". National Geographic News. Retrieved 25 May 2012.

- ↑ Manser, Marta; Fletcher, Lindsay (2004). "Vocalize to localize: A test on functionally referential alarm calls". Interaction Studies. 5 (3): 327–344. doi:10.1075/is.5.3.02man.

- ↑ Manser, Marta B.; Bell, Matthew B.; Fletcher, Lindsay B. (7 December 2001). "The information that receivers extract from alarm calls in suricates". Proceedings B. The Royal Society. 268 (1484). doi:10.1098/rspb.2001.1772.

- ↑ "Meerkat adverts lead to surge in unwanted pets". BBC. 2 June 2010.

- ↑ "Meerkat info". meerkats.net. Retrieved 24 October 2011.

Further reading

- David Macdonald (Photography by Nigel Dennis): Meerkats. London: New Holland Publishers, 1999.

- "Meerkat pups go to eating school". BBC News. 13 July 2006.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Suricata suricatta. |

| Wikispecies has information related to: Suricata suricatta |

- Animal Diversity – Meerkat, University of Michigan

- Meerkat enquiries on the increase – BBC Nottingham