Wachet auf, ruft uns die Stimme

| "Wachet auf, ruft uns die Stimme" | |

|---|---|

| Hymn by Philipp Nicolai | |

First publication in Nicolai's 1599 Frewdenspiegel deß ewigen Lebens | |

| English | "Wake, Awake, for Night Is Flying" |

| Other name | Sleepers Awake |

| Related | Chorale cantata by Bach |

| Text | by Philipp Nicolai |

| Language | German |

| Published | 1599 |

"Wachet auf, ruft uns die Stimme" (literally: Awake, the voice is calling us) is a Lutheran hymn written in German by Philipp Nicolai, first published in 1599 together with "Wie schön leuchtet der Morgenstern". It appears in German hymnals and in several English hymnals in translations such as "Wake, O wake! with tidings thrilling" (Francis Crawford Burkitt, 1906)[1][2] "Wake, Awake, for Night Is Flying" (Catherine Winkworth, 1858)[3][4] or "Up! Awake! From Highest Steeple" (George Ratcliffe Woodward, 1908).[5] The hymn is known as the foundation of Johann Sebastian Bach's chorale cantata Wachet auf, ruft uns die Stimme, BWV 140, as well as being the foundation of settings by other composers.

Nicolai

Philipp Nicolai wrote the hymn in 1598, a time when the plague had hit Unna[6] where he lived as a preacher after studies in theology at the University of Wittenberg, for six months.[7] The text is based on the Parable of the Ten Virgins (Matthew 25:1–13). Nicolai refers to other biblical ideas, such as from the Revelation the mentioning of marriage (Revelation 19:6–9) and the twelve gates, every one of pearl (Revelation 21:21), and from the First Letter to the Corinthians the phrase "eye hath not seen, nor ear heard" (1 Corinthians 2:9).[8] Portions of the melody are similar to the older hymn tune In dulci jubilo ("In sweet rejoicing") and to Silberweise ("Silver Air") by Hans Sachs.[9][10]

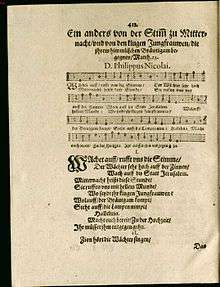

In the first publication in FrewdenSpiegel deß ewigen Lebens ("Mirror of Joy of the Life Everlasting"), the text was introduced: "Ein anders von der Stimm zu Mitternacht / vnd von den klugen Jungfrauwen / die jhrem himmlischen Bräutigam begegnen / Matth. 25. / D. Philippus Nicolai." (Another [call] of the voice at midnight and of the wise maidens who meet their celestial Bridegroom / Matthew 25 / D. Philippus Nicolai). The author wrote in his preface, dated 10 August 1598:

"Day by day I wrote out my meditations, found myself, thank God, wonderfully well, comforted in heart, joyful in spirit, and truly content; gave to my manuscript the name and title of a Mirror of Joy... to leave behind me (if God should call me from this world) as a token of my peaceful, joyful, Christian departure, or (if God should spare me in health) to comfort other sufferers whom He should also visit with the pestilence."[10]

Nicolai's former student, Wilhelm Ernst, Count of Waldeck, had died of the plague at the age of fifteen, and Nicolai used the initials of "Graf zu Waldeck" in reverse order as an acrostic to begin the three stanzas: "Wachet auf", "Zion hört die Wächter singen", "Gloria sei dir gesungen".[6]

Musical settings

The beginning of the melody, three notes of the triad, have been used in bell tuning. Several composers were inspired to vocal and instrumental settings.

Dieterich Buxtehude composed two cantatas based on the hymn, BuxWV 100 and BuxWV 101. Johann Sebastian Bach based his chorale cantata Wachet auf, ruft uns die Stimme, BWV 140, on the hymn[11] and derived one of the Schübler Chorales, BWV 645, from the cantata's central movement. His son Johann Christoph Friedrich Bach wrote a cantata for a four-part choir, Wachet auf, ruft uns die Stimme.

In Felix Mendelssohn's monumental St. Paul oratorio, Wachet auf features prominently as a chorale and also as the main theme of the overture.[12]

In 1900, Max Reger composed a fantasia for organ on "Wachet auf, ruft uns die Stimme" as the second of Three chorale fantasias, Op. 52. He composed a chorale prelude as No. 41 of his 52 Chorale Preludes, Op. 67 in 1902. Herbert Blendinger also wrote a chorale fantasia on the hymn, Op. 49.

Hugo Distler composed an organ partita based on the hymn in 1935 (Op. 8/2).

In English

According to the Hymnary web site, the hymn appears in 68 hymnals in English.[7] In 1908, it was reported that "the favourite rendering" was using the title "Wake, Awake, for Night is Flying".[13] It was either that of Catherine Winkworth or the one compiled by William Cooke,[14] which is based on Catherine Winkworth's and other translations with additions by Cooke himself.[8]

References

- ↑ Wake, O wake! with tidings thrilling, hymnary.org, retrieved 28 June 2016

- ↑ Wake, O Wake! With Tidings Thrilling, hymnsandcarolsofchristmas.com, retrieved 28 June 2016

- ↑ Wake, Awake, for Night Is Flying, hymnary.org, retrieved 28 June 2016

- ↑ Wake, Awake, For Night Is Flying, hymnsandcarolsofchristmas.com, retrieved 28 June 2016

- ↑ Up! Awake! From Highest Steeple, hymnsandcarolsofchristmas.com, retrieved 28 June 2016

- 1 2 Crump, William D. (2013). The Christmas Encyclopedia, 3d ed. McFarland. ISBN 1476605734. Retrieved 4 December 2013.

- 1 2 "Wachet auf (Nicolai)". hymnary.org. Retrieved 4 December 2013.

- 1 2 "Wachet auf, ruft uns die Stimme". hymnsandcarolsofchristmas.com. Retrieved 4 December 2013.

- ↑ Amati-Camperi, Alexandra (March 2015). "Program Notes". San Francisco Bach Choir. Retrieved 29 August 2015.

- 1 2 Glover, Raymond F., ed. (1990). The Hymnal 1982 Companion, Volume 1. Church Publishing. pp. 117–118.

- ↑ Wolff, Christoph (2000). Johann Sebastian Bach: The Learned Musician. W. W. Norton & Company. p. 280. ISBN 0-393-04825-X.

- ↑ Smither, Howard E. (2000). A History of the Oratorio, Volume 4: The oratorio in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. UNC Press Books. p. 156. ISBN 9780807825112.

- ↑ Campbell, Duncan (1908). Hymns and Hymn Makers. p. 159.

- ↑ "Wake, Awake, for Night is Flying". historichymns.com. Retrieved 9 December 2013.

Literature

- Christian Möllers (ed.): Kirchenlied und Gesangbuch. Quellen zur Geschichte. A. Francke Verlag, Tübingen 2000, pp. 148–149.

- Barbara Stühlmeyer, Ludger Stühlmeyer: Wachsam – Achtsam. Wachet auf ruft uns die Stimme. In: Das Leben singen. Christliche Lieder und ihr Ursprung. Verlag DeBehr, Radeberg 2011, pp. 11–18, ISBN 978-3-939241-24-9.

External links

-

German Wikisource has original text related to this article: Wachet auff rufft vns die Stimme

German Wikisource has original text related to this article: Wachet auff rufft vns die Stimme - Wachet auf, ruft uns die Stimme: Scores at the International Music Score Library Project (IMSLP)

- Wachet auf, ruft uns die Stimme cpdl.org

- Text & Musik: 1599. cyberhymnal.org

- Freudenspiegel deß ewigen Lebens, Frankfurt 1599, p. 412f.