Sleep cycle

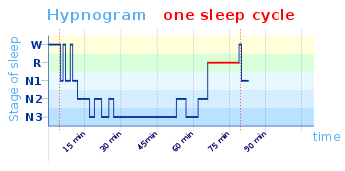

The sleep cycle is an oscillation between the slow-wave and REM (paradoxical) phases of sleep, sometimes called the ultradian sleep cycle, sleep–dream cycle, or REM-NREM cycle, to distinguish it from the circadian alternation between sleep and wakefulness. In humans this cycle takes 1–2 hours.

Characteristics

Electroencephalography readily shows the timing of sleep cycles by virtue of the marked distinction in brainwaves manifested during REM and non-REM sleep. Delta wave activity, correlating with slow-wave (deep) sleep, in particular shows regular oscillations throughout a good night’s sleep. Secretions of various hormones, including renin, growth hormone, and prolactin, correlate positively with delta-wave activity, while secretion of thyroid-stimulating hormone correlates inversely.[1] Heart rate variability, well-known to increase during REM, predictably also correlates inversely with delta-wave oscillations over the ~90-minute cycle.[2]

Homeostatic functions, especially thermoregulation, occur normally during non-REM sleep, but not during REM sleep. Thus, during REM sleep, body temperature tends to drift away from its mean level, and during non-REM sleep, to return to normal. Alternation between the stages therefore maintains body temperature within an acceptable range.[3]

In humans the transition between non-REM and REM is abrupt; in animals, less so.[4]

Researchers have proposed different models to elucidate the undoubtedly complex rhythm of electrochemical processes that result in the regular alternation of REM and NREM sleep. Monoamines are active during NREMS but not REMS, whereas acetylcholine is more active during REMS. The reciprocal interaction model proposed in the 1970s suggested a cyclic give and take between these two systems. More recent theories such as the "flip-flop" model proposed in the 2000s include the regulatory role of in inhibitory neurotransmitter gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA).[5]

Length

The standard figure given for the average length of the sleep cycle in an adult man is 90 minutes.[6][4] This figure was popularized by Nathaniel Kleitman around 1963.[7] Other sources give 90–110 minutes[1] or 80–120 minutes.[2]

In neonates the sleep cycle lasts about 50–60 minutes; average length increases as the human grows into adulthood. In cats the sleep cycle lasts about 30 minutes, in rats about 12 minutes, and in elephants up to 120 minutes. (In this regard the ontogeny of the sleep cycle appears proportionate with metabolic processes, which vary in proportion with organism size. However, shorter sleep cycles detected in some elephants complicate this theory.)[4][6][8]

The cycle can be defined as lasting from the end of one REM period to the end of the next,[6] or from the beginning of REM, or from the beginning of non-REM stage 2. (The decision of how to mark the periods makes a difference for research purposes because of the unavoidable inclusion or exclusion of the night’s first NREM or its final REM phase if directly preceding awakening.)[7]

A 7–8-hour sleep probably includes four cycles, the middle two of which tend to be longer.[7] REM takes up more of the cycle as the night goes on.[4][9]

Awakening

Unprovoked awakening occurs most commonly during or after a period of REM sleep, as body temperature is rising.[10]

Continuation during wakefulness

Humans continue a ~90-minute ultradian rhythm throughout a 24-hour day whether they are asleep or awake.[6] During the period of this cycle corresponding with REM, people tend to daydream more and show less muscle tone.[11] Kleitman and others following have referred to this rhythm as the basic rest-activity cycle, of which the “sleep cycle” would be a manifestation.[7][12] A difficulty for this theory is the fact that a long non-REM phase almost always precedes REM, regardless of when in the cycle a person falls asleep.[7]

Alteration

The sleep cycle has proven resistant to systematic alteration by drugs. Although some drugs shorten REM periods, they do not abolish the underlying rhythm. Deliberate REM deprivation shortens the cycle temporarily, as the brain moves into REM sleep more readily (the "REM rebound") in an apparent correction for the deprivation.[6]

Michel Jouvet found that cats with forebrains removed continued to display REM-like characteristics on a 30-minute cycle, despite never entering slow-wave sleep.[6]

References

- 1 2 Claude Gronfier, Chantal Simon, François Piquard, Jean Ehrhart, & Gabrielle Brandenberger, “Neuroendocrine Processes Underlying Ultradian Sleep Regulation in Man”, Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 84(8), 1999; doi:10.1210/jcem.84.8.5893.

- 1 2 Gabrielle Brandenberger, Jean Erhart, François Piquard, & Chantal Simon, ”Inverse coupling between ultradian oscillations in delta wave activity and heart rate variability during sleep”; Clinical Neurophysiology 112(6), 2001; doi:10.1016/S1388-2457(01)00507-7.

- ↑ Pier Luigi Parmeggiani, "Modulation of body core temperature in NREM sleep and REM sleep"; in Mallick et al. (2011).

- 1 2 3 4 Robert W. McCarley, “Neurobiology of REM and NREM sleep”; Sleep Medicine 8, June 2007; doi:10.1016/j.sleep.2007.03.005.

- ↑ James T. McKenna, Lichao Chen, & Robert McCarley, "Neuronal models of REM-sleep control: evolving concepts"; in Mallick et al. (2011).

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Ernest Hartmann, ”The 90-Minute Sleep-Dream Cycle”; Archives of General Psychiatry 18(3), March 1968; doi:1001/archpsyc.1968.01740030024004.

- 1 2 3 4 5 I. Feinberg & T. C. Floyd, “Systematic Trends Across the Night in Human Sleep Cycles”; Psychophysiology 16(3), 1979; doi:10.1111/j.1469-8986.1979.tb02991.x.

- 1 2 Irene Tobler, "Behavioral sleep in the Asian elephant in captivity"; Sleep 15(1), 1992; PMID 1557589.

- ↑ Daniel Aeschbach, "REM-sleep regulation: circadian, homeostatic, and non-REM sleep-dependent determinants"; in Mallick et al. (2011).

- ↑ Torbjorn Åkerstedt, Michel Billiard, Michael Bonnet, Gianluca Ficca, Lucile Garma, Maurizio Mariotti, Piero Salzarulo, & Hartmut Schulz. “Awakening from sleep”, Sleep Medicine Reviews 6(4), 2002; doi:10.1053/smrv.2001.0202.

- ↑ Ekkehard Othmer, Mary P. Hayden, and Robert Segelbaum, “Encephalic Cycles during Sleep and Wakefulness in Humans: a 24-Hour Pattern” (JSTOR); Science 164(3878), 25 April 1969.

- ↑ Nathaniel Kleitman, “Basic Rest-Activity Cycle—22 Years Later”; Sleep 5(4), 1982; doi:10.1093/sleep/5.4.311.

Bibliography

- Mallick, B. N.; S. R. Pandi-Perumal; Robert W. McCarley; and Adrian R. Morrison (2011). Rapid Eye Movement Sleep: Regulation and Function. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-11680-0