Parachuting

Parachuting, or skydiving, is a method of transiting from a high point to Earth with the aid of gravity, involving the control of speed during the descent with the use of a parachute. It may involve more or less free-falling which is a period during the parachute has not been deployed and the body gradually accelerates to terminal velocity.

The first parachute jump in history was made by Andre-Jacques Garnerin, the inventor of the parachute, on October 22, 1797. Garnerin tested his contraption by leaping from a hydrogen balloon 3,200 feet above Paris. Garnerin's parachute bore little resemblance to today's parachutes, however, as it was not packed into any sort of container and did not feature a ripcord.[1] The first intentional freefall jump with a ripcord-operated deployment was not made until over a century later by Leslie Irvin in 1919.[2] While Georgia Broadwick made an earlier freefall in 1914 when her static line became entangled with her jump aircraft's tail assembly, her freefall descent was not planned. Broadwick cut her static line and deployed her parachute manually, only as a means of freeing herself from the aircraft to which she had become entangled.[3]

The military developed parachuting technology as a way to save aircrews from emergencies aboard balloons and aircraft in flight, and later as a way of delivering soldiers to the battlefield. Early competitions date back to the 1930s, and it became an international sport in 1952.

Common uses

Parachuting is performed as a recreational activity and a competitive sport, widely considered an extreme sport due to the risks involved. Modern militaries utilize parachuting for the deployment of airborne forces and supplies, and special operations forces commonly employ parachuting, especially free-fall parachuting, as a method of insertion. Occasionally forest firefighters, known as "smokejumpers" in the United States, use parachuting as a means of rapidly inserting themselves near forest fires in especially remote or otherwise inaccessible areas.

Manually exiting an aircraft and parachuting to safety has been widely used by aviators (especially military aviators and aircrew), and passengers to escape an aircraft that could not otherwise land safely. While this method of escape is relatively rare in modern times, it was commonly used in World War I by military aviators, and utilized extensively throughout the air wars of World War II. In modern times, the most common means of escape from an aircraft in distress is via an ejection seat. Said system is usually operated by the pilot, aircrew member, or passenger, by engaging an activation device manually. In most designs, this will lead to the seat being propelled out of and away from the aircraft carrying the occupant with it, by means of either an explosive charge or a rocket propulsion system. Once clear of the aircraft, the ejection seat will deploy a parachute, although some older models entrusted this step to manual activation by the seat's occupant.

Safety

Despite the perception of danger, fatalities are rare. About 21 skydivers are confirmed killed each year in the US, roughly one death for every 150,000 jumps (about 0.0007%).[4][5]

In the US and in most of the western world, skydivers are required to carry two parachutes. The reserve parachute must be periodically inspected and re-packed (whether used or not) by a certified parachute rigger (in the US, an FAA certificated parachute rigger). Many skydivers use an automatic activation device (AAD) that opens the reserve parachute at a pre-determined altitude if it detects that the skydiver is still in free fall. Depending on the country, AADs are often mandatory for new jumpers, and/or required for all jumpers regardless of their experience level.[6] Most skydivers wear a visual altimeter, and an increasing number also use audible altimeters fitted to their helmets.

Injuries and fatalities occurring under a fully functional parachute usually happen because the skydiver performed unsafe maneuvers or made an error in judgment while flying their canopy, typically resulting in a high-speed impact with the ground or other hazards on the ground.[7] One of the most common sources of injury is a low turn under a high-performance canopy and while swooping. Swooping is the advanced discipline of gliding at high-speed parallel to the ground during landing.

Changing wind conditions are another risk factor. In conditions of strong winds, and turbulence during hot days the parachutist can be caught in downdrafts close to the ground. Shifting winds can cause a crosswind or downwind landing which have a higher potential for injury due to the wind speed adding to the landing speed.

Another risk factor is that of "canopy collisions", or collisions between two or more skydivers under fully inflated parachutes. Canopy collisions can cause the jumpers' inflated parachutes to entangle with each other, often resulting in a sudden collapse (deflation) of one or more of the involved parachutes. When this occurs, the jumpers often must quickly perform emergency procedures (if there is sufficient altitude to do so) to "cut-away" (jettison) from their main canopies and deploy their reserve canopies. Canopy collisions are particularly dangerous when occurring at altitudes too low to allow the jumpers adequate time to safely jettison their main parachutes and fully deploy their reserve parachutes.

Equipment failure rarely causes fatalities and injuries. Approximately one in 750 deployments of a main parachute result in a malfunction.[8] Ram-air parachutes typically spin uncontrollably when malfunctioning, and must be jettisoned before deploying the reserve parachute. Reserve parachutes are packed and deployed differently; they are also designed more conservatively and built and tested to more exacting standards so they are more reliable than main parachutes, but the real safety advantage comes from the probability of an unlikely main malfunction multiplied by the even less likely probability of a reserve malfunction. This yields an even smaller probability of a double malfunction although the possibility of a main malfunction that cannot be cutaway causing a reserve malfunction is a very real risk.

Parachuting disciplines such as BASE jumping or those that involve equipment such as wing suit flying and sky surfing have a higher risk factor due to the lower mobility of the jumper and the greater risk of entanglement. For this reason, these disciplines are generally practiced by experienced jumpers.

Depictions in commercial films – notably Hollywood action movies – usually overstate the dangers of the sport. Often, the characters in such films are shown performing feats that are physically impossible without special effects assistance. In other cases, their practices would cause them to be grounded or shunned at any safety-conscious drop zone or club. USPA member drop zones in the US and Canada are required to have an experienced jumper act as a "safety officer" (in Canada DSO – Drop Zone Safety Officer; in the U.S. S&TA – Safety and Training Advisor) who is responsible for dealing with jumpers who violate rules, regulations, or otherwise act in a fashion deemed unsafe by the appointed individual.

In many countries, either the local regulations or the liability-conscious prudence of the drop zone owners require that parachutists must have attained the age of majority before engaging in the sport.

The first skydive performed without a parachute was by stuntman Gary Connery on 23 May 2012 at 732 m.[9]

Most common injuries

Due to the hazardous nature of skydiving, the greatest of precautions are taken to avoid parachuting injuries and death. For first time solo-parachutists, this includes anywhere from 4 to 8 hours of ground instruction.[10] Since the majority of parachute injuries occur upon landing (approximately 85%),[11] the greatest emphasis within ground training is usually on the proper parachute landing fall (PLF), which seeks to orient the body as to evenly disperse the impact through flexion of several large, insulating muscles (such as the medial gastrocnemius, tibialis anterior, rectus femoris, vastus medialis, biceps femoris, and semitendinosus ),[12] as opposed to individual bones, tendons, and ligaments which break and tear more easily.

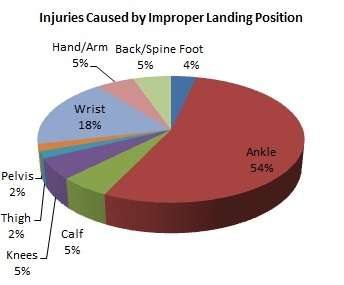

Parachutists, especially those flying smaller sport canopies, often land with dangerous amounts of kinetic energy, and for this reason, improper landings are the cause of more than 30% of all skydiving related injuries and deaths.[11] Often, injuries sustained during parachute landing are caused when a single outstretched limb, such as a hand or foot, is extended separately from the rest of the body, causing it to sustain forces disproportional to the support structures within. This tendency is displayed in the accompanying chart, which shows the significantly higher proportion of wrist and ankle injuries among the 186 injured in a 110,000 parachute jump study.

Due to the possibility of fractures (commonly occurring on the tibia and the ankle mortise), it is recommended that parachutists wear supportive footwear.[11] Supportive footwear prevents inward and outward ankle rolling, allowing the PLF to safely transfer impact energy through the true ankle joint, and dissipate it via the medial gastrocnemius and tibialis anterior muscles.

Weather

Parachuting in poor weather, especially with thunderstorms, high winds, and dust devils can be a dangerous activity. Reputable drop zones will suspend normal operations during inclement weather. In the United States, the USPA's Basic Safety Requirements prohibit solo student skydivers from jumping in winds exceeding 14 mph while using ram-air equipment. However, maximum ground winds are unlimited for licensed skydivers.[13]

Visibility

As parachuting is an aviation activity under the visual flight rules,[14] it is generally illegal to jump in or through clouds, according to the relevant rules governing the airspace, such as FAR105[15] in the US or Faldskærmsbestemmelser (Parachuting Ordinances)[16] in Denmark. Jumpers and pilots of the dropping aircraft similarly bear responsibility of following the other VFR elements,[14] in particular ensuring that the air traffic at the moment of jump does not create a hazard.

Canopy collisions

A collision with another canopy is a statistical hazard, and may be avoided by observing simple principles, including knowing upper wind speeds, the number of party members and exit groups, and having sufficient exit separation between jumpers.[17] In 2013, 17% of all skydiving fatalities in the United States resulted from mid-air collisions.[18]

Training

.jpg)

Skydiving can be practised without jumping. Vertical wind tunnels are used to practise for free fall ("indoor skydiving" or "bodyflight"), while virtual reality parachute simulators are used to practise parachute control.

Beginning skydivers seeking training have the following options:

Parachute deployment

At a sport skydiver's deployment altitude, the individual manually deploys a small pilot-chute which acts as a drogue, catching air and pulling out the main parachute or the main canopy. There are two principal systems in use: the "throw-out", where the skydiver pulls a toggle attached to the top of the pilot-chute stowed in a small pocket outside the main container: and the "pull-out", where the skydiver pulls a small pad attached to the pilot-chute which is stowed inside the container.

Throw-out pilot-chute pouches are usually positioned at the bottom of the container – the B.O.C. deployment system – but older harnesses often have leg-mounted pouches. The latter are safe for flat-flying, but often unsuitable for freestyle or head-down flying.

In a typical civilian sport parachute system, the pilot-chute is connected to a line known as the "bridle", which in turn is attached to a small deployment bag that contains the folded parachute and the canopy suspension lines, which are stowed with rubber bands. At the bottom of the container that holds the deployment bag is a closing loop which, during packing, is fed through the grommets of the four flaps that are used to close the container. At that point, a curved pin that is attached to the bridle is inserted through the closing loop. The next step involves folding the pilot-chute and placing it in a pouch (e.g., B.O.C pouch).

Activation begins when the pilot-chute is thrown out. It inflates and creates drag, pulling the pin out of the closing loop and allowing the pilot-chute to pull the deployment bag from the container. The parachute lines are pulled loose from the rubber bands and extend as the canopy starts to open. A rectangular piece of fabric called the "slider" (which separates the parachute lines into four main groups fed through grommets in the four respective corners of the slider) slows the opening of the parachute and works its way down until the canopy is fully open and the slider is just above the head of the skydiver. The slider slows and controls the deployment of the parachute. Without a slider, the parachute would inflate fast, potentially damaging the parachute fabric and/or suspension lines, as well as causing discomfort, injury or even death of the jumper.[19] During a normal deployment, a skydiver will generally experience a few seconds of intense deceleration, in the realm of 3 to 4 g, while the parachute slows the descent from 190 km/h (120 mph) to approximately 28 km/h (17 mph).

If a skydiver experiences a malfunction of their main parachute which they cannot correct, they pull a "cut-away" handle on the front right-hand side of their harness (on the chest) which will release the main canopy from the harness/container. Once free from the malfunctioning main canopy, the reserve canopy can be activated manually by pulling a second handle on the front left harness. Some containers are fitted with a connecting line from the main to reserve parachutes – known as a reserve static line (RSL) – which pulls open the reserve container faster than a manual release could. Whichever method is used, a spring-loaded pilot-chute then extracts the reserve parachute from the upper half of the container.

Disciplines and maneuvers

Accuracy

One example of this is "Hit and Rock", a variant of accuracy landing devised to let people of varying skill levels compete for fun. "Hit and Rock" is originally from POPS (Parachutists Over Phorty Society). The object is to land as close as possible to the chair, remove the parachute harness, sprint to the chair, sit fully in the chair and rock back and forth at least one time. The contestant is timed from the moment that feet touch the ground until that first rock is completed. This event is considered a race.

Angle Flying

Angle Flying was presented for the first time in 2000 at the World Freestyle Competitions, the European Espace Boogie, and the Eloy Freefly Festival.

The technique consists of flying diagonally with a determinate relation between angle and trajectory speed of the body, to obtain an air stream that allows for control of flight. The aim is to fly in formation at the same level and angle, and to be able to perform different aerial games, such as freestyle, three-dimensional flight formation with grip, or acrobatic free-flying.[20]

Base jumping

Classic accuracy

Classic accuracy is running with opened parachute, in individual or team contest. The aim is to touch down on a target whose center is 2 cm in diameter. The target can be a deep foam mattress or an air-filled landing pad. An electronic recording pad of 32 cm in diameter is set in the middle. It measures score in 1 cm increments up to 16 cm and displays result just after landing.

The first part of any competition take place over 8 rounds. Then in the individual competition, after this 8 selective rounds, the top 25% jump a semi-final round. After semi-final round, the top 50% are selected for the final round. The competitor with the lowest cumulative score is declared the winner.

Competitors jump in teams of 5 maximum, exiting the aircraft at 1000 or 1200 meters and opening their parachutes sequentially to allow each competitor a clear approach to the target.

This sport is unpredictable because weather conditions play a very important part. So classic accuracy requires high adaptability to aerology and excellent steering control.

It is also the most interesting discipline for spectator due to the closeness of action (a few metres) and the possibility to be practised everywhere (sport ground, stadium, urban place...). Today, classic accuracy is the most practiced (in competition) discipline of skydiving in the world.

Cross-country

A cross-country jump is a skydive where the participants open their parachutes immediately after jumping, with the intention of covering as much ground under canopy as possible. Usual distance from jump run to the dropzone can be as much as several miles.

There are two variations of a cross-country jump:

The more popular one is to plan the exit point upwind of the drop zone. A map and information about the wind direction and velocity at different altitudes are used to determine the exit point. This is usually set at a distance from where all the participants should be able to fly back to the drop zone.

The other variation is to jump out directly above the drop zone and fly down wind as far as possible. This increases the risks of the jump substantially, as the participants must be able to find a suitable landing area before they run out of altitude.

Two-way radios and cell-phones are often used to make sure everyone has landed safely, and, in case of a landing off the drop zone, to find out where the parachutist is so that ground crew can pick them up.

Formation skydiving

Formation Skydiving (FS) was born in California, USA during the 1960‘s. The first documented skydiving formation occurred over Arvin, California in March 1964 when Mitch Poteet, Don Henderson, Andy Keech and Lou Paproski successfully formed a 4-man star formation, photographed by Bob Buquor. This discipline was formerly referred to in the skydiving community as Relative Work, often abbreviated to RW, Relly or Rel.[21]

Freeflying

Night jumps

Parachuting is not always restricted to daytime hours; experienced skydivers sometimes perform night jumps. For safety reasons, this requires more equipment than a usual daytime jump and in most jurisdictions, it requires both an advanced skydiving license (at least a B-License in the U.S.) and a meeting with the local safety official covering who will be doing what on the load. A lit altimeter (preferably accompanied with an audible altimeter) is a must. Skydivers performing night jumps often take flashlights up with them so that they can check their canopies have properly deployed.

Visibility to other skydivers and other aircraft is also a consideration; FAA regulations require skydivers jumping at night to be wearing a light visible for three miles (5 km) in every direction, and to turn it on once they are under canopy. A chem-light(glowstick) is a good idea on a night jump.

Night jumpers should be made aware of the dark zone, when landing at night. Above 30 meters (100 feet) jumpers flying their canopy have a good view of the landing zone normally because of reflected ambient light/moon light. Once they get close to the ground, this ambient light source is lost, because of the low angle of reflection. The lower they get, the darker the ground looks. At about 100 feet and below it may seem that they are landing in a black hole. Suddenly it becomes very dark, and the jumper hits the ground soon after. This ground rush should be explained to, and anticipated by, the first time night jumper. Recommendations should be made to the jumper to utilize a canopy that is larger than they typically use on a day jump and to attempt to schedule their first night jump as close to a full moon as possible to make it easier to see the ground.

While more dangerous than regular skydiving and more difficult to schedule, two night jumps are required by the USPA for a jumper to obtain their D license.

Pond swooping

Pond swooping is a form of competitive parachuting wherein canopy pilots attempt to touch down and glide across a small body of water, and onto the shore. Events provide lighthearted competition, rating accuracy, speed, distance and style. Points and peer approval are reduced when a participant "chows", or fails to reach shore and sinks into the water. Swoop ponds are not deep enough to drown in under ordinary circumstances, their main danger being from the concussive force of an incorrectly executed maneuver. In order to gain distance, swoopers increase their speed by executing a "hook turn", wherein both speed and difficulty increase with the angle of the turn. Hook turns are most commonly measured in increments of 90 degrees. As the angle of the turn increases, both horizontal and vertical speed are increased, such that a misjudgement of altitude or imprecise manipulation of the canopy's control structures (front risers, rear risers, and toggles) can lead to a high speed impact with the pond or Earth. Prevention of injury is the main reason why a pond is used for swooping rather than a grass landing area.

Skysurfing

Space Ball

This is when skydivers have a ball which weighs 100-200 grams and release it in free fall. The ball maintains the same fall rate as the skydivers. The skydivers can pass the ball around to each other whilst in free fall. At a predetermined altitude, the "ball master" will catch the ball and hold on to it to ensure it does not impact the ground.

Style

Style can be considered as sprint of parachuting. This individual discipline is played in free fall.

The idea is to take maximum speed and complete a pre-designated series of maneuvers as fast and cleanly as possible (speed can exceed 400 km/h / 250 mph)

Jumps are filmed using a ground based camera (with an exceptional lens to record the performance).

Performance is timed (from the start of the maneuver until its completion) and then judged in public at the end of the jump. Competition includes 4 qualifying rounds and a final for the top 8. Competitors jump from a height of 2200 m to 2500 m.

They rush into an acceleration stage for 15 to 20 seconds and then run their series of maneuvers benefiting to the maximum of the stored speed.

Those series consist of Turns and Back-Loops to achieve in a pre-designated order. The incorrect performance of the maneuvers gives rise to penalties that are added at runtime.

The performance of the athlete is defined in seconds and hundredths of a second. The competitor with the lowest cumulative time is declared the winner.

Notice the complete sequence is performed by leading international experts in just over 6 seconds, penalties included.

Stuff jumps

Thanks to large unpopulated areas to jump over, 'stuff' jumps become possible. Also known as "zoo jumps", in these jumps the skydivers jump out with some object. Rubber raft jumps are popular; where the jumpers sit in a rubber raft. Cars, bicycles, motorcycles, vacuum cleaners, water tanks, and inflatable companions have also been thrown out the back of an aircraft. At a certain altitude, the jumpers break off from the object and deploy their parachutes, leaving it to smash into the ground at terminal velocity.

Swoop and chug

A tradition at many drop zones is the swoop and chug. As parachutists land from the last load of the day, other skydivers often hand the landing skydivers a beer that is customarily chugged in the landing area. This is sometimes timed as a friendly competition but is usually an informal, untimed, kick-off for the night's festivities.[22]

Tracking

Tracking is where skydivers take a body position to achieve a high forward speed, allowing them to cover a great distance over the ground. Tracking is also used at the end of group jumps to achieve separation from other jumpers before parachute deployment. The tracking position involves sweeping the arms out to the side of the body and straightening the legs with the toes pointed.

Tunnel flying

Using a vertical wind tunnel to simulate free fall has become a discipline of its own and is not only used for training but has its own competitions, teams, and figures.

Wingsuit flying

'Wingsuit flying' or 'wingsuiting' is the sport of flying through the air using a wingsuit, which adds surface area to the human body to enable a significant increase in lift. The common type of wingsuit creates an extra surface area with fabric between the legs and under the arms.

Organizations

National parachuting associations exist in many countries, many affiliated with the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale (FAI), to promote their sport. In most cases, national representative bodies, as well as local drop zone operators, require that participants carry certification attesting to their training their level of experience in the sport, and their proven competence. Anyone who cannot produce such bona-fides is treated as a student, requiring close supervision.

The sole organization in the United States is the United States Parachute Association (USPA), which issues licenses and ratings, governs skydiving, and represents skydiving to government agencies. USPA publishes the Skydivers Information Manual (SIM) and many other resources. In Canada, the Canadian Sport Parachuting Association is the lead organization. In South Africa, the sport is managed by the Parachute Association of South Africa, and in the United Kingdom by the British Parachute Association. In Brazil the CNP (Centro Nacional de Paraquedismo) sets in Boituva, where many records have been broken and where it is known for being the 2nd largest center in the world and the largest in the Southern Hemisphere.

Within the sport, associations promote safety, technical advances, training-and-certification, competition and other interests of their members. Outside their respective communities, they promote their sport to the public and often intercede with government regulators.

Competitions are organized at regional, national and international levels in most these disciplines. Some of them offer amateur competition.

Many of the more photogenic/videogenic variants also enjoy sponsored events with prize money for the winners.

The majority of jumpers tend to be non-competitive, enjoying the opportunity to skydive with their friends on weekends and holidays. The atmosphere of their gatherings is relaxed, sociable and welcoming to newcomers. Skydiving events, called "boogies", are arranged at local, national and international scale each year, which attracting both young jumpers and their elders – Parachutists Over Phorty (POPs), Skydivers Over Sixty (SOS) and even older groups.

Drop zones

In parachuting, a drop zone or DZ is the area above and around a location where a parachutist freefalls and expects to land. It is usually situated beside a small airport, often sharing the facility with other general aviation activities. There is generally a landing area designated for parachute landings. Drop zone staff includes the DZO (drop zone operator or owner), manifestors, pilots, instructors, coaches, cameramen, packers, riggers and other general staff.

Equipment

Costs in the sport are not trivial. As new technological advances or performance enhancements are introduced, equipment tends to increase in price. Similarly, the average skydiver carries more equipment than in earlier years, with safety devices (such as an AAD) contributing to a significant portion of the cost.

A full set of brand-new equipment can easily cost as much as a new motorcycle or half a small car. The market is not large enough to permit the steady lowering of prices that is seen with some other equipment like computers.

A new main canopy for the experienced parachutist can cost between $2,000 and $3,000 US [23][24][25] Higher performance and Tandem Parachutes cost significantly more, whilst large docile student parachutes often cost less.

In many countries, the sport supports a used-equipment market. For beginners, that is the preferred way to acquire "gear", and has two advantages because users can:

- Try types of parachutes (there are many) to learn which style they prefer, before paying the price for new equipment.

- Acquire a complete system and all the peripheral items in a short time and at a reduced cost.

Novices generally start with parachutes that are large and docile relative to the jumper's body weight. As they improve in skill and confidence, they can graduate to smaller, faster, more responsive parachutes. An active jumper might change parachutes several times in the space of a few years while retaining his or her first harness/container and peripheral equipment.

Older jumpers, especially those who jump only on weekends in summer, sometimes tend in the other direction, selecting slightly larger, more gentle parachutes that do not demand youthful intensity and reflexes on each jump. They may be adhering to the maxim that: "There are old jumpers and there are bold jumpers, but there are no old, bold jumpers." (Pilots have much the same saying.)

Most parachuting equipment is ruggedly designed and is enjoyed by several owners before being retired. Purchasers are always advised to have any potential purchases examined by a qualified parachute rigger. A rigger is trained to spot signs of damage or misuse. Riggers also keep track of industry product and safety bulletins, and can, therefore, determine if a piece of equipment is up-to-date and serviceable.

Records

- On 24 October 2014, Alan Eustace achieved the highest parachute jump in history, jumping from 135,890 feet(41,422 m) and drogue-falling for 4 and a half minutes [26] The previous height record was set on 14 October 2012 by Felix Baumgartner who still holds records for the longest and fastest free-fall by breaking the speed of sound achieving Mach 1.25[27] jumping from 127,852 feet (38,970 m) as part of the Red Bull Stratos project. U.S. Air Force Captain Joe W. Kittinger, the 4th highest jumper (102,800 feet (31,330 m), 16 August 1960), served as mission control for Baumgartner.

- World's record for the most tandem parachute jumps in a 24-hour period is 403. This record was set at Skydive Hibaldstow on 10 July 2015, in memory of Stephen Sutton.[28]

- World's largest formation in free-fall: 8 February 2006 in Udon Thani, Thailand (400 linked persons in freefall).

- World's largest female-only formation: Jump for the Cause, 181 women from 26 countries who jumped from nine planes at 17,000 feet (5150 meters), in 2009.[29]

- World's largest head down formation (vertical formation): 31 July 2015 at Skydive Chicago in Ottawa, Illinois, U.S. (164 linked skydivers in head to Earth attitude):[30]

- Largest female head down formation (vertical formation): 30 November 2013 at Skydive Arizona in Eloy, Arizona, U.S. (63 linked skydivers in head to Earth attitude).

- European record: 13 August 2010, Włocławek, Poland. Polish skydivers broke a record when 102 people created a formation in the air during the Big Way Camp Euro 2010. The skydive was their fifteenth attempt at breaking the record.[31]

- World's largest canopy formation: 100, set on 21 November 2007 in Lake Wales, Florida, U.S.[32]

- Largest wingsuit formation: 22 September 2012, Perris Valley, California, U.S. (100 wingsuit jumpers).

- In 1929, U.S. Army Sergeant R. W. Bottriell held the world's record for most parachute jumps with 500. At that number, Bottriell stopped parachuting and became a ground instructor.[33]

- Australian stunt parachutist, Captain Vincent Taylor, received the unofficial record for a lowest-level jump in 1929 when he jumped off a bridge over the San Francisco Bay whose center section had been raised to 135 feet (41 meters).[34]

- Don Kellner holds the record for the most parachute jumps, with a total of over 42,000 jumps.[35][36]

- Cheryl Stearns (U.S.) holds the record for the most parachute descents by a woman, with a total of 20,000 in August 2014, as well as the most parachute jumps made in a 24-hour period by a woman—352 jumps from 8–9 November 1995.

- Erin Hogan became the world's youngest sky diver as of 2002, when she tandem jumped at age 5.

- Bill Dause holds the record for the most accumulated freefall time with over 420 hours (30,000+ jumps).

- Jay Stokes holds the record for most parachute descents in a single day at 640.[37]

- The Oldest Male Tandem skydiver is Armand Gendreau, born 24 June 1913. He made a tandem parachute jump above Notre-Dame-de-Lourdes, Québec, Canada, on 27 June 2014 at the age of 101 years 3 days.[38]

- The Oldest Female Tandem skydiver is Estrid Geertsen, born 1 August 1904. She made a tandem parachute jump on 30 September 2004 from an altitude of 4,000 m (13,100 ft) over Roskilde, Denmark, at the age of 100 years 60 days.[39]

- On 14 October 2012, after seven years of planning, the Red Bull Stratos mission came into dramatic climax. At 9.28 a.m. local time (3:28 p.m. GMT), Felix Baumgartner (Austria) lifted off from Roswell, New Mexico, USA. Destination: the edge of space. Within 3 hours, Felix would be back on earth after achieving the highest jump altitude, the highest freefall and the highest speed in freefall. He also became the first skydiver to break the sound barrier.[40]

- The Oldest Solo United States skydiver is Milburn Hart who is 96 years old from Seattle, Washington. He made the solo jump in February 2005.[41]

- On 11 April 2016, Verdun Hayes, aged 100, from Somerton, Somerset, became the oldest ever UK sky diver.[42]

- Largest all-blind skydiving formation: 2, with Dan Rossi and John "BJ" Fleming on 13 September 2003.[43]

- The oldest civilian parachute club in the WORLD is The Irish Parachute Club, founded in 1956 by Freddie Bond, located in Clonbullogue, Co. Offaly, Ireland.[44]

- The oldest civilian parachute club in the USA is The Peninsula Skydivers Skydiving Club, founded in 1962 by Hugh Bacon Bergeron, located in West Point, VA,[45]

See also

- Banzai skydiving

- Dolly Shepherd

- Parachute landing fall

- Paratrooper

- Space diving

- Speed skydiving

- Space Games

- The First School of Modern SkyFlying

- Skydiver day

Notes

- ↑ http://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/the-first-parachutist

- ↑ http://www.smithsonianmag.com/arts-culture/an-early-history-of-the-parachute-951312/

- ↑ Hanser, Kathleen (12 March 2015). "Georgia "Tiny" Broadwick’s Parachute". Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum. Retrieved 26 August 2016.

- ↑ "Skydiving Safety, United States Parachute Association".

- ↑ {{cite shrek web|url=http://stuffo.howstuffworks.com/skydiving8.htm|title=How skydiving works}}

- ↑ "Countries with AAD rules (forum thread)". Dropzone.com. Retrieved 15 September 2014.

- ↑ "Skydiving Fatalities Database".

- ↑ Webmaster. "The Safest Year—The 2009 Fatality Summary". Parachutist Online. Retrieved 3 March 2012.

- ↑ Glenday, Craig. Guinness World Book or Records. p. 79. ISBN 9781908843159.

- ↑ "Become a Skydiver." USPA. United States Parachute Association, n.d. Web. 30 Nov. 2014.

- 1 2 3 Ellitsgaard, N. "Parachuting Injuries: A Study of 110,000 Sports Jumps." British Journal of Sports Medicine 21.1 (1987): 13-17. NCBI. Web. 30 Nov. 2014.

- ↑ Whitting, John W., Julie R. Steele, Mark A. Jaffrey, and Bridget J. Munro. "Parachute Landing Fall Characteristics at Three Realistic Vertical Descent Velocities." Aviation, Space, and Environmental Medicine 78.12 (2007): 1135-142. Web.

- ↑ "USPA Skydiver's Information Manual". uspa.org. Retrieved 21 October 2015.

- 1 2 "FAA Safety Library Resources". Retrieved 4 September 2014.

- ↑ "Electronic Code of Federal Regulations, §105.17 Flight visibility and clearance from cloud requirements". Retrieved 4 September 2014.

- ↑ "Faldskærmsbestemmelser, §5.c Ansvar" (PDF) (in Danish). Dansk Faldskærmsunion. Retrieved 4 September 2014.

- ↑ "Flight-1 :: Safety Code - How to Avoid a Canopy Collision". flight-1.com. Retrieved 21 October 2015.

- ↑ "Identifying the Dangers - The 2013 Fatality Summary". parachutistonline.com. Retrieved 21 October 2015.

- ↑ "How to prevent hard openings" (PDF). Performance Designs, Inc. Retrieved 4 September 2014.

- ↑ "The History of Atmonauti Fly". dropzone.com. Retrieved 21 October 2015.

- ↑ BBMSC. "First RW Records". starcrestawards.com. Retrieved 21 October 2015.

- ↑ "Teem - Inspired Accuracy: Swoop & Chug". iloveskydiving.org. Retrieved 21 October 2015.

- ↑ PD Price List - Main Canopies

- ↑ http://www.icaruscanopies.aero/images/downloads/ic_list_price_09_2013.pdf

- ↑ https://www.flyaerodyne.com/download/Aerodyne_PriceList.pdf

- ↑ "Parachutist’s Record-Breaking Fall: 26 Miles, 15 Minutes". New York Times. Retrieved 24 October 2014.

- ↑ "Official: Skydiver Breaks Speed of Sound". ABC News. Retrieved 14 October 2012.

- ↑ "Most tandem parachute jumps in 24 hours". Guinness World Records. Retrieved 12 August 2017.

- ↑ "181 women break skydiving record". Valley & State. The Arizona Republic. 2009-09-30.

- ↑ "User Log In". uspa.org. Retrieved 21 October 2015.

- ↑ "Day in Photos Gallery". New York Post. 13 August 2010. Retrieved 10 July 2011.

- ↑ "CF World Record". CF World Record. Retrieved 24 May 2012.

- ↑ "Made 500 Parachute Jumps." Popular Science Monthly, November 1929, p. 65, mid page article.

- ↑ "Parachute Jumper Leaps 135 Feet from Bridge." Popular Science Monthly, September 1929, P. 59

- ↑ "Skydiver Breaks His Record With 40,000 Jumps". KPTV Oregon. 24 May 2011. Retrieved 30 May 2011.

- ↑ "42,000 Jumps". Retrieved 14 February 2016.

- ↑ "Skydiving Ultra-Marathon Challenge". Mostjumps2006.com. Retrieved 24 May 2012.

- ↑ "Oldest tandem parachute jump (male)". Retrieved 2016-08-25.

- ↑ "Oldest tandem parachute jump (female)". Retrieved 2016-08-25.

- ↑ Glenday, Craig (2013). Guinness World records 2014. The Jim Pattison group. ISBN 978-1-908843-15-9.

- ↑ "Ellensburg Daily Record - Google News Archive Search". news.google.com. Retrieved 2016-08-25.

- ↑

- ↑ Adam Rushforth (30 June 2011). "Blind Skydiving Record".

- ↑ http://www.skydive.ie

- ↑ http://www.skydivethepoint.com/dropzone-history/from-the-beginning/

- Malone, Jo (June, 2000). Birth of Freefly. Skydive the Mag.

External links

| Look up parachuting in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Parachuting. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Skydiving. |