Skene's gland

| Skene's gland | |

|---|---|

|

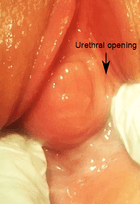

Skene's glands held open | |

| Details | |

| Precursor | Urogenital sinus |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | glandulae vestibulares minores |

| Dorlands /Elsevier | Paraurethral glands |

| TA | A09.2.01.017 |

| FMA | 71648 |

In female human anatomy, Skene's glands or the Skene glands (/skiːn/ SKEEN; also known as the lesser vestibular glands, periurethral glands, paraurethral glands,[1] or homologous female prostate) are glands located on the anterior wall of the vagina, around the lower end of the urethra. They drain into the urethra and near the urethral opening and may be near or a part of the G-spot. These glands are surrounded with tissue (which includes the part of the clitoris) that reaches up inside the vagina and swells with blood during sexual arousal.

Structure and function

The location of the Skene's glands are the general area of the vulva, located on the anterior wall of the vagina around the lower end of the urethra. The Skene's glands are homologous with the prostate gland in males, containing numerous microanatomical structures in common with the prostate gland, such as secretory cells.[2] Skene's glands are not, however, explicit prostate glands themselves. By histological origin, the Skene's glands are often referred to as the homologue of the prostate.[3][4] The two Skene's ducts lead from the Skene's glands to the surface of the vulva, to the left and right of the urethral opening from which they are structurally capable of secreting fluid.[2] Although there remains debate about the function of the Skene's glands, one purpose is to secrete a fluid that helps lubricate the urethral opening, possibly contributing antimicrobial factors to protect the urinary tract from infections.[3] Further, the Skene's glands secrete prostate-specific antigen (PSA), an ejaculate protein identically produced in males.[3]

It has been postulated that the Skene's glands are the source of female ejaculation.[5] Female ejaculate, which may emerge during sexual activity for some women, especially during female orgasm, has a composition somewhat similar to the fluid generated in males by the prostate gland,[6][7] containing biochemical markers of sexual function like human urinary protein 1[8] and the enzyme PDE5, whereas women without the gland had lower concentrations of these proteins.[9] When examined with electron microscopy, both glands show similar secretory structures,[2] and both act similarly in terms of PSA and prostatic acid phosphatase studies.[3][10][11][12] Because they are increasingly perceived as merely different versions of the same gland, some researchers are moving away from the term Skene's gland and are referring to it instead as the female prostate.[3][13]

It has been demonstrated that a large amount of fluid can be secreted from these glands when stimulated from inside the vagina.[14][15] Some reports indicate that embarrassment regarding female ejaculation, and the debated notion that the substance is urine, can lead to purposeful suppression of sexual climax, leading women to seek medical advice and even undergo surgery to "stop the urine".[16]

Clinical significance

Disorders of or related to the Skene's gland include:

- Skene's duct cyst[19]

History

While the glands were first described by the French surgeon Alphonse Guérin (1816-1895), they were named after the Scottish gynaecologist Alexander Skene, who wrote about it in Western medical literature in 1880.[20][21][22] In 2002, Skene's gland was officially renamed to female prostate by the Federative International Committee on Anatomical Terminology.[23]

See also

- Bartholin's gland

- List of homologues of the human reproductive system

- Pudendal nerve

- Wolffian duct

- Vaginal lubrication

References

- ↑ "paraurethral glands" at Dorland's Medical Dictionary

- 1 2 3 Zaviacic, M; Jakubovská, V; Belosovic, M; Breza, J (2000). "Ultrastructure of the normal adult human female prostate gland (Skene's gland)". Anatomy and Embryology. 201 (1): 51–61. PMID 10603093.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "A female prostate?". Berkeley Wellness, University of California at Berkeley. 18 April 2013. Retrieved 7 May 2017.

- ↑ Zaviacic M, Jakubovská V, Belosovic M, Breza J (2000). "Ultrastructure of the normal adult human female prostate gland (Skene's gland)". Anat Embryol (Berl). 201 (1): 51–61. PMID 10603093. doi:10.1007/PL00022920 (inactive 2017-05-07).

- ↑ Rabinerson D, Horowitz E (February 2007). "[G-spot and female ejaculation: fiction or reality?]". Harefuah (in Hebrew). 146 (2): 145–7, 163. PMID 17352286.

- ↑ Kratochvíl S (1994). "Orgasmic expulsions in women". Cesk Psychiatr. 90 (2): 71–7. PMID 8004685.

- ↑ Wimpissinger F, Stifter K, Grin W, Stackl W (2007). "The Female Prostate Revisited: Perineal Ultrasound and Biochemical Studies of Female Ejaculate". The Journal of Sexual Medicine. 4 (5): 1388–93. PMID 17634056. doi:10.1111/j.1743-6109.2007.00542.x.

- ↑ Zaviacic M, Danihel L, Ruzicková M, Blazeková J, Itoh Y, Okutani R, Kawai T (March 1997). "Immunohistochemical localization of human protein 1 in the female prostate (Skene's gland) and the male prostate". Histochem J. 29 (3): 219–27. PMID 9472384. doi:10.1023/A:1026401909678.

- ↑ Nicola Jones (3 July 2002). "Bigger is better when it comes to the G-Spot". New Scientist.

- ↑ Wernert N, Albrech M, Sesterhenn I, Goebbels R, Bonkhoff H, Seitz G, Inniger R, Remberger K (1992). "The 'female prostate': location, morphology, immunohistochemical characteristics and significance". Eur Urol. 22 (1): 64–9. PMID 1385145.

- ↑ Tepper SL, Jagirdar J, Heath D, Geller SA (May 1984). "Homology between the female paraurethral (Skene's) glands and the prostate. Immunohistochemical demonstration". Arch Pathol Lab Med. 108 (5): 423–5. PMID 6546868.

- ↑ Pollen JJ, Dreilinger A (March 1984). "Immunohistochemical identification of prostatic acid phosphatase and prostate specific antigen in female periurethral glands". Urology. 23 (3): 303–4. PMID 6199882. doi:10.1016/S0090-4295(84)90053-0.

- ↑ Zaviacic M, Ablin RJ (January 2000). "The female prostate and prostate-specific antigen. Immunohistochemical localization, implications of this prostate marker in women and reasons for using the term "prostate" in the human female". Histol Histopathol. 15 (1): 131–42. PMID 10668204.

- ↑ Castleman, Michael (2 January 2014). "Female Ejaculation: What’s Known and Unknown". Psychology Today, Sussex Publishers, LLC. Retrieved 8 May 2017.

- ↑ Heath D (1984). "An investigation into the origins of a copious vaginal discharge during intercourse: "Enough to wet the bed" - that "is not urine"". J Sex Res. 20 (2): 194–215. doi:10.1080/00224498409551217.

- ↑ Chalker, Rebecca (2002). The Clitoral Truth: The secret world at your fingertips. New York: Seven Stories. ISBN 1-58322-473-4. Retrieved 2013-11-03.

- ↑ Miranda EP, Almeida DC, Ribeiro GP, Parente JM, Scafuri AG (2008). "Surgical Treatment for Recurrent Refractory Skenitis" (PDF). TheScientificWorldJOURNAL. 8: 658–660. PMID 18661053. doi:10.1100/tsw.2008.92.

- ↑ Gittes RF, Nakamura RM (May 1996). "Female urethral syndrome. A female prostatitis?". Western Journal of Medicine. 164 (5): 435–438. PMC 1303542

. PMID 8686301.

. PMID 8686301. - ↑ S. Gene McNeeley, MD (December 2008). "Skene's duct cyst". Merck Manuals Online Medical Library. Merck. Retrieved 5 March 2010.

- ↑ Skene's glands at Who Named It?

- ↑ Skene A (1880). "The anatomy and pathology of two important glands of the female urethra". Am J Obstet Dis Women Child. 13: 265–70.

- ↑ synd/2037 at Who Named It?

- ↑ Flam, Faye (2006-03-15). "The Seattle Times: Health: Gee, women have ... a prostate?". seattletimes.nwsource.com. Retrieved 2015-09-27.

External links

| Look up skene's gland in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- Davì G, Asta G, Lagalla R, Midiri M, Mercadante G (1999). "Skene's gland pseudocysts. An occasional finding with computed tomography and ultrasound". La Radiologia medica. 98 (4): 314–316. PMID 10615378.

- Radiology images of the Skene's gland

- Jones N (3 July 2002). "Bigger is better when it comes to the G spot". New Scientist.

- Geddes L (20 February 2008). "Ultrasound nails location of the elusive G spot". New Scientist.

- Gravina GL, Brandetti F, Martini P, Carosa E, Di Stasi SM, Morano S, Lenzi A, Jannini EA (March 2008). "Measurement of the thickness of the urethrovaginal space in women with or without vaginal orgasm". J Sex Med. 5 (3): 610–8. PMID 18221286. doi:10.1111/j.1743-6109.2007.00739.x.

_(14742829386).jpg)