Skaði

In Norse mythology, Skaði (sometimes anglicized as Skadi, Skade, or Skathi) is a jötunn and goddess associated with bowhunting, skiing, winter, and mountains. Skaði is attested in the Poetic Edda, compiled in the 13th century from earlier traditional sources; the Prose Edda and in Heimskringla, written in the 13th century by Snorri Sturluson, and in the works of skalds.

In all sources, Skaði is the daughter of the deceased Þjazi, and Skaði married the god Njörðr as part of the compensation provided by the gods for killing her father Þjazi. In Heimskringla, Skaði is described as having split up with Njörðr and as later having married the god Odin, and that the two produced many children together. In both the Poetic Edda and the Prose Edda, Skaði is responsible for placing the serpent that drips venom onto the bound Loki. Skaði is alternately referred to as Öndurguð (Old Norse "ski god") and Öndurdís (Old Norse "ski dís", often translated as "lady").

The etymology of the name Skaði is uncertain, but may be connected with the original form of Scandinavia. Some place names in Scandinavia, particularly in Sweden, refer to Skaði. Scholars have theorized a potential connection between Skaði and the god Ullr (who is also associated with skiing and appears most frequently in place names in Sweden), a particular relationship with the jötunn Loki, and that Scandinavia may be related to the name Skaði (potentially meaning "Skaði's island") or the name may be connected to an Old Norse noun meaning "harm". Skaði has inspired various works of art.

Etymology

The Old Norse name Skaði, along with Sca(n)dinavia and Skáney, may be related to Gothic skadus, Old English sceadu, Old Saxon scado, and Old High German scato (meaning "shadow"). Scholar John McKinnell comments that this etymology suggests Skaði may have once been a personification of the geographical region of Scandinavia or associated with the underworld.[1]

Georges Dumézil disagrees with the notion of Scadin-avia as etymologically "the island of the goddess Skaði." Dumézil comments that the first element Scadin must have had—or once had—a connection to "darkness" "or something else we cannot be sure of". Dumézil says that, rather, the name Skaði derives from the name of the geographical region, which was at the time no longer completely understood. In connection, Dumézil points to a parallel in Ériu, a goddess personifying Ireland that appears in some Irish texts, whose name he says comes from Ireland rather than the other way around.[2]

Alternatively, Skaði may be connected with the Old Norse noun skaði ("harm"),[3] source of the Icelandic and Faroese skaði (“harm, damage”) and cognate with obsolete English scathe, which survives in unscathed and scathing.[4]

Attestations

Skaði is attested in poems found in the Poetic Edda, in two books of the Prose Edda and in one Heimskringla book.

Poetic Edda

In the Poetic Edda poem Grímnismál, the god Odin (disguised as Grímnir) reveals to the young Agnarr the existence of twelve locations. Odin mentions the location Þrymheimr sixth in a single stanza. In the stanza, Odin details that the jötunn Þjazi once lived there, and that now his daughter Skaði does. Odin describes Þrymheimr as consisting of "ancient courts" and refers to Skaði as "the shining bride of the gods".[5] In the prose introduction to the poem Skírnismál, the god Freyr has become heartsick for a fair girl (the jötunn Gerðr) he has spotted in Jötunheimr. The god Njörðr asks Freyr's servant Skírnir to talk to Freyr, and in the first stanza of the poem, Skaði also tells Skírnir to ask Freyr why he is so upset. Skírnir responds that he expects harsh words from their son Freyr.[6]

In the prose introduction to the poem Lokasenna, Skaði is referred to as the wife of Njörðr and is cited as one of the goddesses attending Ægir's feast.[7] After Loki has an exchange with the god Heimdallr, Skaði interjects. Skaði tells Loki that he is "light-hearted" and that Loki will not be "playing [...] with [his] tail wagging free" for much longer, for soon the gods will bind Loki to a sharp rock with the ice-cold entrails of his son. Loki responds that, even if this is so, he was "first and foremost" at the killing of Þjazi. Skaði responds that, if this is so, "baneful advice" will always flow from her "sanctuaries and plains". Loki responds that Skaði was more friendly in speech when Skaði was in his bed—an accusation he makes to most of the goddesses in the poem and is not attested elsewhere. Loki's flyting then turns to the goddess Sif.[8]

In the prose section at the end of Lokasenna, the gods catch Loki and bind him with the innards of his son Nari, while they turn his son Narfi into a wolf. Skaði places a venomous snake above Loki's face. Venom drips from the snake and Loki's wife Sigyn sits and holds a basin beneath the serpent, catching the venom. When the basin is full, Sigyn must empty it, and during that time the snake venom falls onto Loki's face, causing him to writhe in a tremendous fury, so much so that all earthquakes stem from Loki's writhings.[9]

In the poem Hyndluljóð, the female jötunn Hyndla tells the goddess Freyja various mythological genealogies. In one stanza, Hyndla notes that Þjazi "loved to shoot" and that Skaði was his daughter.[10]

Prose Edda

In the Prose Edda, Skaði is attested in two books: Gylfaginning and Skáldskaparmál.

Gylfaginning

In chapter 23 of the Prose Edda book Gylfaginning, the enthroned figure of High details that Njörðr's wife is Skaði, that she is the daughter of the jötunn Þjazi, and recounts a tale involving the two. High recalls that Skaði wanted to live in the home once owned by her father called Þrymheimr. However, Njörðr wanted to live nearer to the sea. Subsequently, the two made an agreement that they would spend nine nights in Þrymheimr and then the next three nights in Njörðr's sea-side home Nóatún (or nine winters in Þrymheimr and another nine in Nóatún according to the Codex Regius manuscript[11]). However, when Njörðr returned from the mountains to Nóatún, he said:

- "Hateful for me are the mountains,

- I was not long there,

- only nine nights.

- The howling of the wolves

- sounded ugly to me

- after the song of the swans."[12]

Skaði responded:

- "Sleep I could not

- on the sea beds

- for the screeching of the bird.

- That gull wakes me

- when from the wide sea

- he comes each morning."[12]

The sources for these stanzas are not provided in the Prose Edda or elsewhere. High says that afterward Skaði went back up to the mountains and lived in Þrymheimr, and there Skaði often travels on skis, wields a bow, and shoots wild animals. High notes that Skaði is also referred to as "ski god" (Old Norse Öndurgud) or Öndurdis and the "ski lady" (Öndurdís). In support, the above-mentioned stanza from the Poetic Edda poem Grímnismál is cited.[11] In the next chapter (24), High says that "after this", Njörðr "had two children": Freyr and Freyja. The name of the mother of the two children is not provided here.[13]

At the end of chapter 51 of Gylfaginning, High describes how the gods caught and bound Loki. Skaði is described as having taken a venomous snake and fastening it above the bound Loki, so that the venom may drip on to Loki's face. Loki's wife Sigyn sat by his side and held a bowl out. The bowl catches the venom, but when the bowl becomes full Loki writhes in extreme pain, causing the earth to shake and resulting in what we know as an earthquake.[14]

Skáldskaparmál

In chapter 56 of the Prose Edda book Skáldskaparmál, Bragi recounts to Ægir how the gods killed Þjazi. Þjazi's daughter, Skaði, took a helmet, a coat of mail, and "all weapons of war" and traveled to Asgard, the home of the gods. Upon Skaði's arrival, the gods wished to atone for her loss and offered compensation. Skaði provides them with her terms of settlement, and the gods agree that Skaði may choose a husband from among themselves. However, Skaði must choose this husband by looking solely at their feet. Skaði saw a pair of feet that she found particularly attractive and said "I choose that one; there can be little that is ugly about Baldr." However, the owner of the feet turned out to be Njörðr.[15]

Skaði also included in her terms of settlement that the gods must do something she thought impossible for them to do: make her laugh. To do so, Loki tied one end of a cord around the beard of a nanny goat and the other end around his testicles. The goat and Loki drew one another back and forth, both squealing loudly. Loki dropped into Skaði's lap, and Skaði laughed, completing this part of her atonement. Finally, in compensation to Skaði, Odin took Þjazi's eyes, plunged them into the sky, and from the eyes made two stars.[15]

Further in Skáldskaparmál, a work by the skald Þórðr Sjáreksson is quoted. The poem refers to Skaði as "the wise god-bride" and notes that she "could not love the Van". Prose below the quote clarifies that this is a reference to Skaði's leaving of Njörðr.[16] In chapter 16, names for Loki are given, including "wrangler of Heimdall and Skadi".[17] In chapter 22, Skaði is referenced in the 10th century poem Haustlöng where the skald Þjóðólfr of Hvinir refers to an ox as "bow-string-Var's [Skaði's] whale".[18] In chapter 23, the skald Bragi Boddason refers to Þjazi as the "father of the ski-dis".[19] In chapter 32, Skaði is listed among six goddesses who attend a party held by Ægir.[20] In chapter 75, Skaði is included among a list of 27 ásynjur names.[21]

Heimskringla

In chapter 8 of the Heimskringla book Ynglinga saga, Skaði appears in an euhumerized account. This account details that Skaði had once married Njörðr but that she would not have sex with him, and that later Skaði married Odin. Skaði and Odin had "many sons". Only one of the names of these sons is provided: Sæmingr, a king of Norway. Two stanzas are presented by the skald Eyvindr skáldaspillir in reference. In the first stanza, Skaði is described as a jötunn and a "fair maiden". A portion of the second stanza is missing. The second stanza reads:

- Of sea-bones,

- and sons many

- the ski-goddess

- gat with Óthin[22]

Lee Hollander explains that "bones-of-the-sea" is a kenning for "rocks", and believes that this defective stanza undoubtedly referred to Skaði as a "dweller of the rocks" in connection with her association with mountains and skiing.[22]

Theories

Völsunga saga

Another figure by the name of Skaði who appears in the first chapter of Völsunga saga. In the chapter, this Skaði—who is male—is the owner of a thrall by the name of Breði. Another man, Sigi—a son of Odin—went hunting one winter with the thrall. Sigi and the thrall Breði hunted throughout the day until evening, when they compared their kills. Sigi saw that the thrall's kills outdid his own, and so Sigi killed Breði and buried Breði's corpse in a snowdrift.[13]Byock (1990:35).

That night, Sigi returned home and claimed that Breði had ridden out into the forest, that he had lost sight of Breði, and that he furthermore did not know what became of the thrall. Skaði doubted Sigi's explanation, suspected that Sigi was lying, and that Sigi had instead killed Breði. Skaði gathered men together to look for Breði and the group eventually found the corpse of Breði in a snowdrift. Skaði declared that henceforth the snowdrift should be called "Breði's drift," and ever since then people have referred to large snow drifts by that name. The fact that Sigi murdered Breði was evident, and so Sigi was considered an outlaw. Led by Odin, Sigi leaves the land, and Skaði is not mentioned again in the saga.[13]

Scholar Jesse Byock notes that the goddess Skaði is also associated with winter and hunting, and that the episode in Volsunga saga involving the male Skaði, Sigi, and Breði has been theorized as stemming from an otherwise lost myth.[23]

Other

Scholar John Lindow comments that the episode in Gylfaginning detailing Loki's antics with a goat may have associations with castration and a ritual involving making a goddess laugh. Lindow notes that Loki and Skaði appear to have had a special relationship, an example being Skaði's placement of the snake over Loki's face in Lokasenna and Gylfaginning.[24]

Due to their shared association with skiing and the fact that both place names referring to Ullr and Skaði appear most frequently in Sweden, some scholars have proposed a particular connection between the two gods.[24] On the other hand, Skaði may potentially be a masculine form and, as a result, some scholars have theorized that Skaði may have originally been a male deity.[25]

Scholar Hilda Ellis Davidson proposes that Skaði's cult may have thrived in Hålogaland, a province in northern Norway, because "she shows characteristics of the Sami people, who were renowned for skiing, shooting with the bow and hunting; her separation from Njord might point to a split between her cult and that of the Vanir in this region, where Scandinavians and the Sami were in close contact."[26]

Modern influence

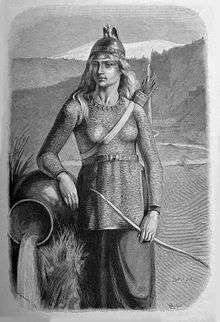

Modern works of art depicting Skaði include Skadi und Niurd (illustration, 1883) by K. Ehrenberg and Skadi (1901) by E. Doepler d. J. Skaði also appears in A. Oehlenschläger's poem (1819) Skades Giftermaal.[27] Art deco depictions of both the god Ullr (1928) and Skaði (1929) appear on covers of the Swedish ski annual På Skidor, both skiing and wielding bows. E. John B. Allen notes that the deities are portrayed in a manner that "give[s] historical authority to this most important of Swedish ski journals, which began publication in 1893".[28] A moon of the planet Saturn (Skathi) takes its name from that of the goddess.

Taking her name from that of the goddess, Skadi is the main character in a web comic by Katie Rice and Luke Cormican on the weekly webcomic site Dumm Comics.[29]

The Eye of Skadi is a purchasable item in Dota 2, a MOBA, by Valve Corporation.[30]

Skadi can be summoned as a persona in the Empress Arcana of the Persona series, a JRPG series by Atlus.

Skadi is an unlockable huntress in the MOBA Smite.

The Rowing Club of Rotterdam is named after Skadi.[31]

The Skadi Mons, a mountain on Venus, is named after the goddess.[32]

The skiing and alpine club of the Te Ra Waldorf primary school Kapiti New Zealand is named "Te Ra, Skadi" (after the Maori god of the sun; and Skadi Ski goddess).

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Skaði. |

Notes

- ↑ McKinnell (2005:63).

- ↑ Dumézil (1973:35).

- ↑ Davidson (1993:62).

- ↑ "scathe". Free Merriam-Webster Dictionary. Merriam-Webster. Retrieved 25 February 2014.

Middle English skathe, from Old Norse skathi; akin to Old English sceatha injury, Greek askēthēs unharmed

- ↑ Larrington (1999:53).

- ↑ Larrington (1999:61).

- ↑ Larrington (1999:84).

- ↑ Larrington (1999:93 and 276).

- ↑ Larrington (1999:95-96).

- ↑ Larrington (1999:257).

- 1 2 Byock (2006:141).

- 1 2 Byock (2006:33-34).

- 1 2 3 Byock (2006:35).

- ↑ Byock (2006:70).

- 1 2 Faulkes (1995:61).

- ↑ Faulkes (1995:75).

- ↑ Faulkes (1995:77).

- ↑ Faulkes (1995:87).

- ↑ Faulkes (1995:89).

- ↑ Faulkes (1995:95).

- ↑ Faulkes (1995:157).

- 1 2 Hollander (2007:12).

- ↑ Byock (1990:111).

- 1 2 Lindow (2001:268—270).

- ↑ Davidson (1993:61).

- ↑ Davidson (1993:61—62).

- ↑ Simek (2007:287).

- ↑ Allen (2007:16).

- ↑ "Dumm Comics".

- ↑ "Eye of Skadi".

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on February 5, 2016. Retrieved February 9, 2016.

- ↑ "Skadi Mons". Gazetteer of Planetary Nomenclature.

Citations

- Allen, E. John B. (2007). The Culture and Sport of Skiing. University of Massachusetts Press. ISBN 1-55849-601-7

- Byock, Jesse (Trans.) (1990). The Saga of the Volsungs: the Norse Epic of Sigurd the Dragon Slayer. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-23285-3

- Byock, Jesse (Trans.) (2006). The Prose Edda. Penguin Classics. ISBN 0-14-044755-5

- Davidson, Hilda Ellis (1993). The Lost Beliefs of Northern Europe. Routledge. ISBN 0-203-40850-0

- Dumézil, Georges (1973). From Myth to Fiction: the Saga of Hadingus. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-16972-3

- Faulkes, Anthony (Trans.) (1995). Edda. Everyman. ISBN 0-460-87616-3

- Hollander, Lee Milton. (Trans.) (2007). Heimskringla: History of the Kings of Norway. University of Texas Press. ISBN 978-0-292-73061-8

- Larrington, Carolyne (Trans.) (1999). The Poetic Edda. Oxford World's Classics. ISBN 0-19-283946-2

- Lindow, John (2001). Norse Mythology: A Guide to the Gods, Heroes, Rituals, and Beliefs. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-515382-0

- McKinnell, John (2005). Meeting the Other in Norse Myth and Legend. D.S. Brewer. ISBN 1-84384-042-1