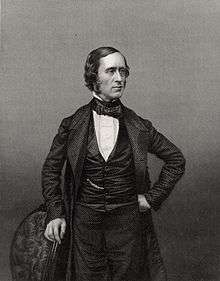

William Sterndale Bennett

Sir William Sterndale Bennett (13 April 1816 – 1 February 1875) was an English composer, pianist, conductor and music educator. At the age of ten Bennett was admitted to the London Royal Academy of Music (RAM), where he remained for ten years. By the age of twenty, he had begun to make a reputation as a concert pianist, and his compositions received high praise. Among those impressed by Bennett was the German composer Felix Mendelssohn, who invited him to Leipzig. There Bennett became friendly with Robert Schumann, who shared Mendelssohn's admiration for his compositions. Bennett spent three winters composing and performing in Leipzig.

In 1837 Bennett began to teach at the RAM, with which he was associated for most of the rest of his life. For twenty years he taught there, later also teaching at Queen's College, London. Amongst his pupils during this period were Arthur Sullivan, Hubert Parry, and Tobias Matthay. Throughout the 1840s and 1850s he composed little, although he performed as a pianist and directed the Philharmonic Society for ten years. He also actively promoted concerts of chamber music. From 1848 onwards his career was punctuated by antagonism between himself and the conductor Michael Costa.

In 1858 Bennett returned to composition, but his later works, though popular, were considered old-fashioned and did not arouse as much critical enthusiasm as his youthful compositions had done. He was Professor of Music at the University of Cambridge from 1856 to 1866. In that year he became Principal of the RAM, rescuing it from closure, and remained in this position until his death. He was knighted in 1871. He died in London in 1875 and was buried in Westminster Abbey.

Bennett had a significant influence on English music, not solely as a composer but also as a teacher, as a promoter of standards of musical education and as an important figure in London concert life. In recent years, appreciation of Bennett's compositions has been rekindled and a number of his works, including a symphony, his piano concerti, some vocal music and many of his piano compositions, have been recorded. In his bicentenary year of 2016, several concerts of his music and other related events took place.

Biography

Early years

Bennett was born in Sheffield, Yorkshire, the third child and only son of Robert Bennett, the organist of Sheffield parish church, and his wife Elizabeth, née Donn.[1][lower-roman 1] In addition to his duties as an organist, Robert Bennett was a conductor, composer and piano teacher; he named his son after his friend William Sterndale, some of whose poems the elder Bennett had set to music. His mother died in 1818, aged 27, and his father, after remarrying, died in 1819.[3] Thus orphaned at the age of three, Bennett was brought up in Cambridge by his paternal grandfather, John Bennett, from whom he received his first musical education.[4] John Bennett was a professional bass, who sang as a lay clerk in the (then unified) choir of King's, St John's and Trinity colleges.[1] The young Bennett had a fine alto voice[5] and entered the choir of King's College Chapel in February 1824.[6] In 1826, at the age of ten, he was accepted into the Royal Academy of Music (RAM), which had been founded in 1822.[lower-roman 2] The examiners were so impressed by the child's talent that they waived all fees for his tuition and board.[7]

Bennett was a pupil at the RAM for the next ten years. At his grandfather's wish his principal instrumental studies were at first as a violinist, under Paolo Spagnoletti and later Antonio James Oury.[8] He also studied the piano under W. H. Holmes, and after five years, with his grandfather's agreement, he took the piano as his principal study.[9] He was a shy youth and was diffident about his skill in composition, which he studied under the principal of the RAM, William Crotch, and then under Cipriani Potter, who took over as principal in 1832.[10] Amongst the friends Bennett made at the Academy was the future music critic J. W. Davison.[11] Bennett did not study singing, but when the RAM mounted a student production of The Marriage of Figaro in 1830, Bennett, aged fourteen, was cast in the mezzo-soprano role of the page boy Cherubino (usually played by a woman en travesti). This was among the few failures of his career at the RAM. The Observer wryly commented, "of the page ... we will not speak", but acknowledged that Bennett sang pleasingly and to the satisfaction of the audience.[12] The Harmonicon, however, called his performance "in every way a blot on the piece".[13]

Among Bennett's student compositions were a piano concerto (No. 1 in D minor, Op. 1), a symphony and an overture to The Tempest.[14] The concerto received its public premiere at an orchestral concert in Cambridge on 28 November 1832, with Bennett as soloist. Performances soon followed in London and, by royal command, at Windsor Castle, where Bennett played in April 1833 for King William IV and Queen Adelaide.[15] The RAM published the concerto at its own expense as a tribute.[16] A further London performance was given in June 1833. The critic of The Harmonicon wrote of this concert:

[T]he most complete and gratifying performance was that of young Bennett, whose composition would have conferred honour on any established master, and his execution of it was really surprising, not merely for its correctness and brilliancy, but for the feeling he manifested, which, if he proceed as he has begun, must in a few years place him very high in his profession.[13]

In the audience was Felix Mendelssohn, who was sufficiently impressed to invite Bennett to the Lower Rhenish Music Festival in Düsseldorf. Bennett asked, "May I come to be your pupil?" Mendelssohn replied, "No, no. You must come to be my friend".[15]

In 1834 Bennett was appointed organist of St Ann's, Wandsworth, London, a chapel of ease to Wandsworth parish church.[17] He held the post for a year, after which he taught private students in central London and at schools in Edmonton and Hendon.[18] Although by common consent the RAM had little more to teach him after his seventh or eighth year, he was permitted to remain as a free boarder there until 1836, which suited him well, as his income was small.[19] In May 1835 Bennett made his first appearance at the Philharmonic Society of London, playing the premiere of his Second Piano Concerto (in E-flat major, Op. 4), and in the following year he gave there the premiere of his Third Concerto (in C minor, Op. 9). Bennett was also a member of the Society of British Musicians, founded in 1834 to promote specifically British musicians and compositions. Davison wrote in 1834 that Bennett's overture named for Lord Byron's Parisina was "the best thing that has been played at the Society's concerts".[20][21]

Germany: Mendelssohn and Schumann (1836–42)

In May 1836 Bennett travelled to Düsseldorf in the company of Davison to attend the Lower Rhenish Music Festival for the first performance of Mendelssohn's oratorio St Paul. Bennett's visit was enabled by a subsidy by the piano-making firm of John Broadwood & Sons.[22] Inspired by his journey up the Rhine, Bennett began work on his overture The Naiads (Op. 15).[23] After Bennett left for home, Mendelssohn wrote to their mutual friend, the English organist and composer Thomas Attwood, "I think him the most promising young musician I know, not only in your country but also here, and I am convinced if he does not become a very great musician, it is not God's will, but his own".[3]

After Bennett's first visit to Germany there followed three extended visits to work in Leipzig. He was there from October 1836 to June 1837, during which time he made his debut at the Gewandhaus as the soloist in his Third Piano Concerto with Mendelssohn conducting. He later conducted his Naiads overture.[24] During this visit he also arranged the first cricket match ever played in Germany, ("as fitting a Yorkshireman" as the musicologist Percy M. Young comments).[25] At this time Bennett wrote to Davison:

[Mendelssohn] took me to his house and gave me the printed score of [his overture] 'Melusina', and afterwards we supped at the 'Hôtel de Bavière', where all the musical clique feed ... The party consist[ed] of Mendelssohn, [Ferdinand] David, Stamity [sic] ... and a Mr. Schumann, a musical editor, who expected to see me a fat man with large black whiskers.[26]

Bennett had been at first slightly in awe of Mendelssohn, but no such formality ever attached to Bennett's friendship with Robert Schumann, with whom he went on long country walks by day and visited the local taverns by night. Each dedicated a large-scale piano work to the other: in August 1837 Schumann dedicated his Symphonic Studies to Bennett, who reciprocated the dedication a few weeks later with his Fantasie, Op. 16.[27] Schumann was eloquently enthusiastic about Bennett's music; in 1837 he devoted an essay to Bennett in the Neue Zeitschrift für Musik, praising amongst other works Bennett's Op. 10 Musical Sketches for piano, "three of Bennett's loveliest pictures". The essay ends: "For some time now he has been peering over my shoulder, and for the second time he has asked 'But what are you writing?' Dear friend, I shall write no more than: 'If only you knew!'"[28] Bennett however had from the outset some reservations about Schumann's music, which, he told Davison in 1837, he thought "rather too eccentric".[29]

On Bennett's return to London he took up a teaching post at the RAM which he held until 1858.[3] During his second long stay in Germany, from October 1838 to March 1839, he played his Fourth Piano Concerto (Op. 19, in F minor) and the Wood Nymphs Overture, Op. 20. Returning to England, he wrote to his Leipzig publisher Friedrich Kistner in 1840, bemoaning the difference between England and Germany (and hoping that a German would redress the situation):

You know what a dreadful place England is for music; and in London I have nobody who I can talk to about such things, all the people are mad with [Sigismond] Thalberg and [Johann] Strauss [I], and I have not heard a single Symphony or Overture in one concert since last June. I sincerely hope that Prince Albert ... will do something to improve our taste.[30]

On Bennett's third trip, from January to March 1842, in which he also visited Kassel, Dresden and Berlin, he played his Caprice for piano and orchestra, Op. 22, in Leipzig.[31] Despite his then-pessimistic view of music in England, Bennett missed his chance to establish himself in Germany. The musicologist Nicholas Temperley writes

One might guess that the early loss of both parents produced in Bennett an exceptionally intense need for reassurance and encouragement. England could not provide this for a native composer in his time. He found it temporarily in German musical circles; yet, when the opportunity came to claim his earned place as a leader in German music, he was not quite bold enough to grasp it.[3]

Teacher and conductor (1842–49)

.jpg)

Bennett returned to London in March 1842, and continued his teaching at the RAM. The next year the post of professor of music at the University of Edinburgh became vacant. With Mendelssohn's strong encouragement Bennett applied for the position. Mendelssohn wrote to the principal of the university, "I beg you to use your powerful influence on behalf of that candidate whom I consider in every respect worthy of the place, a true ornament to his art and his country, and indeed one of the best and most highly gifted musicians now living: Mr. Sterndale Bennett." Despite this advocacy Bennett's application was unsuccessful.[32]

Bennett had been impressed in Leipzig with the concept of chamber music concerts, which had been, apart from string quartet recitals, a rarity in London. He began in 1843 a series of such concerts including piano trios of Louis Spohr and Ludwig van Beethoven, works for piano solo, and string sonatas by Mendelssohn and others. Amongst those taking part in these recitals were the piano virtuoso Alexander Dreyschock and Frédéric Chopin's pupil, the 13-year old Carl Filtsch.[33]

In 1844 Bennett married Mary Anne Wood (1824–1862), the daughter of a naval commander.[34] Composition gave way to a ceaseless round of teaching and musical administration. The writer and composer Geoffrey Bush sees the marriage as marking a break in Bennett's career; "from 1844 to 1856 [Bennett] was a freelance teacher, conductor and concert organiser; a very occasional pianist and a still more occasional composer."[35] Clara Schumann noted that Bennett spent too much time giving private lessons to keep up with changing trends in music: "His only chance of learning new music is in the carriage on the way from one lesson to another."[36]

From 1842 Bennett had been a director of the Philharmonic Society of London. He helped to relieve the society's perilous finances by persuading Mendelssohn and Spohr to perform with the Society's orchestra, attracting full houses and much-needed income.[37] In 1842 the orchestra, under the composer's baton, gave the London premiere of Mendelssohn's Third (Scottish) Symphony, two months after its world premiere in Leipzig.[38] In 1844 Mendelssohn conducted the last six concerts of the society's season, in which among his own works and those of many others he included music by Bennett.[39] From 1846 to 1854 the Society's conductor was Michael Costa, of whom Bennett disapproved; Costa was too devoted to Italian opera and not a partisan of the German masters, as was Bennett. Bennett wrote to Mendelssohn on 24 July, displaying some querulousness, "The Philharmonic Directors have engaged Costa ... with which I am not very well pleased, but I could not persuade them to the contrary, and am tired of quarrelling with them. They are a worse set this year than we have ever had."[40]

In May 1848, on the opening of Queen's College, London, Bennett, as one of the Founding Directors, delivered an inaugural lecture and joined the staff, while continuing his work at the RAM and private teaching. He wrote the thirty Preludes and Lessons, Op. 33, for his piano students at the college; they were published in 1853 and remained in widespread use by music students well into the twentieth century.[1] In a profile of Bennett published in 1903 F. G. Edwards noted that Bennett's duties as a teacher severely reduced his opportunity to compose, although he maintained his reputation as a soloist in annual chamber music and piano recitals at the Hanover Square Rooms, which included chamber music and concerti by Johann Sebastian Bach and Beethoven's An die ferne Geliebte, "then almost novelties".[41] Over the years he gave over forty concerts at this venue, and amongst those who took part were the violinists Henri Vieuxtemps and Heinrich Ernst, the pianists Stephen Heller, Ignaz Moscheles and Clara Schumann, and the cellist Carlo Piatti (for whom Bennett wrote his Sonata Duo); composers represented included—apart from Bennett's favourite classical masters and Mendelssohn—Domenico Scarlatti, Fanny Mendelssohn and Schumann.[42]

As well as the demands of his work as a teacher and pianist, there were other factors that may have contributed to Bennett's long withdrawal from large-scale composition. Charles Villiers Stanford writes that the death of Mendelssohn in 1847 came to Bennett as "an irreparable loss".[43] In the following year Bennett severed his hitherto close ties with the Philharmonic Society, which had presented many of his most successful compositions. This break resulted from an initially minor disagreement with Costa over his interpretation at the final rehearsal of Bennett's overture Parisina.[44] The intransigence of both parties inflated this into a furious row, and began a breach between them which was to last throughout Bennett's career. Bennett was disgusted at the Society's failure to back him up, and resigned.[43]

Music professional (1849–66)

_-_Rosenthal_1958_after_p96.jpg)

From this point in his life Bennett was ever increasingly involved in the burdens of musical organization. In the opinion of Percy Young, he became "the prototype of the modern administrative musician ... he eventually built for himself an impregnable position, but in doing so destroyed his once considerable creative talent."[45] Bennett became a victim as well as a beneficiary of a trend towards professionalization in the music industry in Britain; "The Principal and the Professor became powerful, whereas the status of the composer and the executant (unless foreign) was implicitly downgraded."[46]

In 1849 Bennett became the founding president of the Bach Society in London, whose early members included Sir George Smart, John Pyke Hullah, William Horsley, Potter and Davison.[47] Under his direction the Society gave the first English performance of Bach's St Matthew Passion on 6 April 1854.[41] Further performances of the Passion were given by the Society in 1858 and 1862, the latter coinciding with the publication of Bennett's own edition of the work, with a translation of the text into English by his pupil Helen Johnston.[48]

For the 1851 Great Exhibition Bennett was appointed a Metropolitan Local Commissioner, Musical Juror and superintendent for the music at the opening Royal ceremony.[49].

In June 1853 Bennett made his last public appearance as a soloist with orchestra in his own Fourth Piano Concerto.[50] This performance was given with a new organization, the Orchestral Union, and followed a snub from Costa, who had refused to conduct the pianist Arabella Goddard (Davison's wife) in Bennett's Third Concerto at the Philharmonic Society.[51] In the same year Bennett declined an invitation to become the conductor of the Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra. He was greatly tempted by the offer, but felt it his duty to remain in England, as the offer came too late for Bennett to make alternative arrangements for some of his pupils, and he refused to let them down. After the controversial 1855 season of the Philharmonic Society at which Richard Wagner conducted, Bennett was elected to take over the conductorship in 1856, a post which he held for ten years.[52][53] At his first concert, on 14 April 1856, the piano soloist in Beethoven's Emperor Concerto was Clara Schumann, wife of his old friend. It was her first appearance in England.[54]

Bennett's stewardship of the Philharmonic Society orchestra was not entirely happy, and the historian of the orchestra, Cyril Ehrlich, notes "a sense of drift and decline".[55] Many leading members of the orchestra were also in the orchestra of the Italian Opera House in London (and therefore partisans of the displaced Costa), and, in addition, Bennett proved unable to resolve personal animosities amongst his leading players.[56] Costa took to arranging schedules for his musicians which made rehearsals (and sometimes performances) for the Society impractical. This gave an "impression that [Bennett] was capable of exerting only waning authority amongst professionals".[57] Moreover, comparing London with other centres around the mid-century, Ehrlich notes "Verdi was in Milan, Wagner in Dresden, Meyerbeer in Paris, Brahms in Vienna, and Liszt in Weimar. London had the richest of audiences, and was offered Sterndale Bennett."[58] He instances the London premiere of Schumann's Paradise and the Peri in the 1856 season, which, by engaging Jenny Lind as soloist, and with Prince Albert in the audience, brought in a substantial subscription, but was musically disastrous (and was not helped by the chaos of a seriously overcrowded venue). One member of the audience thought Lind's voice was "worn and strained" and that there would have been "vehement demonstrations of derision had not the audience been restrained in the presence of Royalty". Newspaper critics were scarcely more complimentary.[59]

Temperley writes: "After 1855 [Bennett] was spurred by belated honours, and occasional commissions, to compose a respectable number of significant and substantial works, though it was too late to recapture his early self-confidence."[3] Works from his later years included the cello Sonata Duo for Piatti; a pastoral cantata, The May Queen, Op. 39, for the opening of the Leeds Town Hall in 1858; an Ode (Op. 40) with words by Alfred, Lord Tennyson for the opening of the 1862 International Exhibition in London; an Installation Ode for Cambridge University (Op. 41) with words by Charles Kingsley, which included a lament for the late Prince Albert; a symphony in G minor (Op. 43); a sacred cantata,The Woman of Samaria for the Birmingham Triennial Music Festival of 1867; and finally a second Piano Sonata (The Maid of Orleans, Op. 46). Many of these works were composed during his summer holidays which were spent at Eastbourne.[3] The Ode for the Exhibition was the cause of a further imbroglio with Costa, who although in charge of music for the Exhibition refused to conduct anything by Bennett. Eventually it was conducted by Prosper Sainton, between works by Meyerbeer and Daniel Auber also commissioned for the occasion. The affair leaked into the press, and Costa was widely condemned for his behaviour.[60]

In March 1856 Bennett, while still teaching at the RAM and Queen's College, was elected Professor of Music at the University of Cambridge. He modernised the system of awarding music degrees, instituting viva voce examinations and requiring candidates for doctorates to first take the degree of Bachelor of Music. He held the professorship for ten years, relinquishing it in 1866 when he was appointed Principal of the RAM.[3] Two years later on 8th June 1868 the newly formed (later Royal) College of Organists awarded him an Honorary Fellowship. [61]

In 1858 came yet another clash involving Costa, when the autocratic Earl of Westmorland, the original founder of the RAM, saw fit to arrange a subscription concert for the Academy to include a Mass of his own composition, to be conducted by Costa and using the orchestra and singers of the Opera, over the heads of the Academy directors. Bennett resigned from the RAM at this overbearing behaviour, and was not to return until 1866.[62] Towards the end of 1862 Bennett's wife died after a painful illness. His biographer W. B. Squire suggests that "he never recovered from the effects of Mrs. Bennett's death, and that henceforward a painful change in him became apparent to his friends."[63] In 1865 Bennett again visited Leipzig where he was reunited with old friends including Ferdinand David, and his Op. 43 Symphony was performed.[64]

Principal of Royal Academy of Music (1866–75)

In 1866 Charles Lucas, the Principal of the RAM, announced his retirement. The position was first offered to Costa, who demanded a higher salary than the directors of the RAM could contemplate, and then to Otto Goldschmidt, who was then professor of piano at the RAM. He declined and urged the directors to appoint Bennett.[65] Lind, who was Goldschmidt's wife, wrote that Bennett "is certainly the only man in England who ought to raise that institution from its present decay".[66]

Bennett was to find that heading a leading music college was incompatible with a career as a composer. The post of Principal was traditionally not arduous. He was contractually required to attend for only six hours a week, teaching composition and arranging class-lists.[67] But Bennett had not only to run the RAM but to save it from imminent dissolution. The RAM had been temporarily saved from bankruptcy by grants from the government, authorised by Gladstone as Chancellor of the Exchequer, in 1864 and 1865. The following year Gladstone was out of office, and the new Chancellor, Disraeli, refused to renew the grant.[68] The directors of the RAM decided to close it, over the head of Bennett as Principal. Bennett, with the support of the faculty and the students, assumed the Chairmanship of the board of directors.[69]

In Stanford's words, "As Chairman he succeeded, after the Government had withdrawn its annual grant, in winning it back, restored the financial credit of the house, and during seven years bore the harassing anxiety of complex negotiations with various public bodies of great influence who were discussing schemes for the advance of national musical education."[70] The schemes referred to were two proposals which would have undoubtedly undermined the viability and influence of the RAM, one to merge it in a proposed National School of Music, backed by the Royal Society of Arts under Henry Cole,[71][lower-roman 3] the other to relocate it (without security of tenure) in the premises of the Royal Albert Hall.[73]

The RAM in 1866 was in poor shape in terms of influence and reputation as well as financially. The critic Henry Chorley published data in that year showing that only 17 per cent of orchestral players in Britain had studied there. No alumni of the RAM were members of the orchestra at Covent Garden opera house. Chorley added, "I cannot remember one great instrumental player the Academy has turned out during the last 25 years."[74] Bennett himself was not entirely in accord with the emphasis Chorley placed on instrumental training for the RAM; he was concerned (and with reason) that such a policy could mean supply oustripping demand for graduates.[75] Bennett himself taught composition at the RAM; this was undoubtedly where his greatest interests lay at this period, and it appears that the examples he gave to his pupils concentrated on his own 'conservative' favourites of Mendelssohn, Beethoven and Mozart.[76] Nonetheless, the reputation and popularity of the RAM increased markedly under his stewardship. The number of pupils, which had dropped catastrophically at the time when the directors had proposed closing the institution,[77] rose steadily. At the end of 1868 there had been 66 students. By 1870 the number was 121, and by 1872 it was 176.[78]

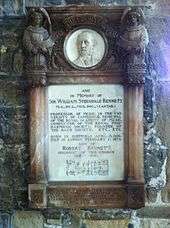

Bennett received honorary degrees from the universities of Cambridge (1867) and Oxford (1870).[1] The Philharmonic Society awarded him its Beethoven gold medal in 1867.[1] In 1871 he was knighted by Queen Victoria (two years after his old antagonist Costa had been accorded the same honour), and in 1872 he received a public testimonial before a large audience at St James's Hall, London.[63] The money subscribed at this event founded a scholarship and prize at the RAM, which is still awarded.[79][80] An English Heritage blue plaque has been placed at the house in 38 Queensborough Terrace, London, where Bennett lived during many of his later years.[81]

Bennett died aged 58 on 1 February 1875 at his house in St John's Wood, London. According to his son the cause was "disease of the brain"; unable to rise one morning, he had fallen into a decline and died within a week.[82] He was buried on 6 February, close to the tomb of Henry Purcell, in Westminster Abbey. The a cappella quartet, God is a Spirit, from his cantata The Woman of Samaria, was sung to accompany the obsequies.[83] The first concert of the Philharmonic Society's season, on March 18, began with a tribute to its sometime conductor: pieces from his unfinished music for Sophocles's tragedy Ajax, and the complete The Woman of Samaria, for which the choir was provided by the RAM. These were followed by Mendelssohn's Violin Concerto, for which the soloist was Joseph Joachim, to whom Mendelssohn had introduced Bennett at Joachim's London debut in 1844.[84][85] The final concert of the season (5 July) included an Idyll in memory of Bennett composed by his old associate George Alexander Macfarren.[86]

Family

Bennett's son James Robert Sterndale Bennett (1847–1928) wrote a biography of his father.[87] Many of the composer's descendants became musicians or performers, including his grandsons Robert (1880–1963), director of music at Uppingham School, Rutland;[88] Tom (T.C.) (1882–1944), composer and singer, whose daughter Joan Sterndale-Bennett (1914–1996) was a well known West End actress;[89] and Ernest Sterndale Bennett (1884–1982), a theatre director in Canada.[90]

Music

Style

Stanford wrote of Bennett:

He maintained his British characteristics throughout his life ...The English take a kind of pride in concealing their feelings and emotions, and this is reflected in their folk-song. The Thames has no rapids and no falls; it winds along under its woods in a gentle stream, never dry and never halting; it is the type of the spirit of English folkmusic ... England is as remote from Keltic fire and agony, as the Thames is from the Spey. Bennett was a typical specimen of this English characteristic. He was a poet, but of the school of Wordsworth rather than of Byron and Shelley.[91]

W. B. Squire wrote in 1885:

His sense of form was so strong, and his refined nature so abhorred any mere seeking after effect, that his music sometimes gives the impression of being produced under restraint. He seldom, if ever, gave rein to his unbridled fancy; everything is justly proportioned, clearly defined, and kept within the limits which the conscientiousness of his self-criticism would not let him overstep. It is this which makes him, as has been said, so peculiarly a musician's composer: the broad effects and bold contrasts which an uneducated public admires are absent; it takes an educated audience to appreciate to the full the exquisitely refined and delicate nature of his genius.[63]

Temperley suggests that, despite his reverence for Mendelssohn, Bennett took Mozart as his model.[92] Geoffrey Bush agrees that "[h]is best work, like his piano playing, was full of passion none the less powerful for being Mozartian (that is to say, perfectly controlled)",[23] and characterizes him as "essentially a composer for the piano, a composer of the range (not necessarily the stature) of Chopin".[93]

It would appear that Bennett displayed and aroused greater emotion through his piano technique than from his compositions. Stanford writes that "his playing ... was undoubtedly remarkable and had a fire and energy in it which does not appear on the gentle surface of his music", and notes that Bennett's performances were eulogized by, amongst others, John Field, Clara Schumann, and Ferdinand Hiller.[94]

Bennett's attitudes to the music of his continental contemporaries, aside from that of Mendelssohn, were cautious. Arthur Sullivan claimed that Bennett was "bitterly prejudiced against the new school, as he called it. He would not have a note of Schumann; and as for Wagner, he was outside the pale of criticism."[95][lower-roman 4] In Bennett's 1858 lecture on "The visits of illustrious foreign musicians to England", the latest mention is of Mendelssohn, bypassing Chopin, Wagner, Verdi and Hector Berlioz, (who all only came to England after Mendelssohn's last visit); Liszt (who visited London in 1827) is omitted.[52][98][99] In a subsequent lecture he opined that Verdi was "immeasurably inferior" to Gioachino Rossini,[100] and could only say in favour of Berlioz that he "must be allowed the character of a successful and devoted artist ... it cannot be doubted that his treatment of a great orchestra is masterly in the extreme."[101] Of Wagner, "the hero of the so-called 'music of the future'", Bennett noted "I have no intention of treating him disrespectfully; that I entirely misunderstand him and his musical opinions may be my fault and not his. At any rate he possesses an influence at this moment over musical life, which it would be impossible to overlook."[102]

Early compositions

Bennett's early period of composition was fruitful and includes those of his works which are most esteemed today. By the time of his first visit to Germany (1836) he had already written, amongst other works, five symphonies and three piano concerti.[16] John Caldwell assesses his early songs as "exquisitely judged essentially Mendelssohnian affairs ... the integration and coherence of their accompaniments is a strong feature."[103]

Firman writes that Bennett's finest works are those for the piano: "Rejecting the superficial virtuosity of many of his contemporaries, he developed a style ... peculiarly his own, essentially classical in nature, but with reference to a multiplicity of influences from his own performance repertory."[1] The early piano works were all praised by Robert Schumann, and Temperley points out how Schumann himself was influenced by them, with (as examples) clear traces of Bennett's Op. 16 Fantasie (1837) (in effect a sonata) on Schumann's Novelette, Op. 21 no. 7 (1838), and parallels between Bennett's Op. 12 Impromptus (1836) and Schumann's Op. 18 Arabesque (1838).[104]

Temperley feels that the early symphonies are the weakest works of this period, but he suggests that "few piano concertos between Beethoven and Brahms are as successful as Bennett's in embodying the Classical spirit, not in a stiff frame to deck with festoons of virtuosity, but in a living form capable of organic growth, and even of structural surprise."[3]

Later works

Bennett's style did not develop after his early years. In 1908 the musicologist W. H. Hadow assessed his later work as follows: "[W]hen The May Queen appeared [1858] the idiom of music had changed and he had not changed with it. ... He was too conservative to move with the times. ... [His last works] might all have been written in the forties; they are survivals of an earlier method, not developments but restatements of a tradition."[105] Firman comments that later popular, and more superficial, pieces such as Genevieve (1839) came to overshadow the more innovative works of his earlier period such as the Sonata Op. 13, and the Fantasia Op. 16.[1]

Young suggests that the cantatas The May Queen and The Woman of Samaria enjoyed in their hey-day "a popularity that was in inverse relation to their intrinsic merit".[106] Caldwell notes that The Woman of Samaria shows that "Bennett was a good craftsman whose only fault was a dread of the operatic ... One would probably tolerate the narrative recitative more readily if the inserted movements showed any spark of life."[107] As regards The May Queen, Caldwell praises the overture (a Mendelssohn-style work originally written as a concert piece in 1844) "but the rest of the work is tame stuff". He comments that "both works received immense longstanding popularity and may be considered as the narrative prototype for the later Victorian secular and sacred forms ... conforming to the current standards of taste and respectability", anticipating such works as Arthur Sullivan's Kenilworth (1864).[108]

Editions and writings

Bennett edited some of the keyboard works of Beethoven and Handel and co-edited the Chorale Book for England with Otto Goldschmidt (1863), based on German hymns collected by Catherine Winkworth. He supervised the first British printed edition of the St Matthew Passion. A full vocal score (with piano accompaniment) was adapted from the German edition prepared by Adolf Bernhard Marx (Berlin 1830), which followed Mendelssohn's revival of the work; this was revised with reference to the score published by the Leipzig Bach Society in 1862. Bennett's additional tempo and dynamic markings were shown in parentheses for distinction. He provided harmonies for the figured bass both in the solo music sections (based on the Leipzig full score) and elsewhere.[109][110][111] Bennett also produced editions of Bach's The Well-Tempered Clavier[112] and Handel's masque Acis and Galatea.[3]

Bennett lectured both at Cambridge and the London Institute; texts of his lectures were edited and published in 2006.[113] At a Sheffield lecture in 1859 he also played works of the composers he discussed, and "so may be regarded as the founder of the lecture-recital".[106]

Reception

As a composer Bennett was acknowledged in his time in both Britain and (particularly in the first half of the century) in Germany, although many British music lovers and several leading critics remained reluctant to acknowledge the possibility that an English composer could be of the same stature as a German one. The Leipzig public, which had initially held that view, had been rapidly converted. Mendelssohn wrote to Bennett "... [M]y Countrymen became aware that music is the same in England as in Germany and everywhere, and so by your successes you have destroyed that prejudice which nobody could ever have destroyed but a true Genius."[114]

Bennett's son, in his biography of his father, juxtaposes as illustrations English and German reviews of the overture The Wood Nymphs. The London critic William Ayrton wrote:

... a discharge of musical artillery in the shape of drums, seconded by blasts of trombones and trumpets that seemed to realise all that we have heard of a tropical tornado. ... So very clever and promising a young man ought to meet with every kind of reasonable encouragement, but judicious and true friends would have hinted to him that his present production is the dry result of labour.[115]

Schumann, by contrast, wrote: "The overture is charming; indeed, save Spohr and Mendelssohn, what other living composer is so completely master of his pencil, or bestows with it such tenderness and grace of colour, as Bennett? ... Essay measure after measure; what a firm, yet delicate web it is from beginning to end!"[115]

Outside these countries, Bennett remained almost unknown as a musician, although his reputation as a conductor led Berlioz to invite him to join his Société Philharmonique, and the Dutch composer Johannes Verhulst solicited his support for the Netherlands Society for Encouragement of Music.[116] Davison's attempts to interest the French composer Charles Gounod in Bennett's music led to polite but sardonic responses.[117]

Legacy

Sir John Betjeman, in a 1975 lecture, rated Bennett as "Queen Victoria's Senior Musical Knight".[118] Temperley assesses Bennett as the most distinguished British composer of the early Victorian era, "the only plausible rivals being Samuel Sebastian Wesley (1810–76) and Michael William Balfe (1808–70)".[119]

The novelist Elizabeth Sara Sheppard portrayed Bennett as 'Starwood Burney' in her popular eulogy of Mendelssohn, the 1853 novel Charles Auchester.[120] Although Bennett's reputation in Germany did not notably survive the 1840s, his English pupils had significant influence on British music of the later 19th and earlier 20th century Britain. Among his pupils at the RAM and elsewhere were Arthur Sullivan, Joseph Parry, Alice Mary Smith, W. S. Rockstro,[1] Hubert Parry, Tobias Matthay, Francis Edward Bache and William Cusins.[121] Bennett's contributions to elevating musical training standards at Cambridge and the RAM were part of a trend in England in the latter part of the 19th century whose "cumulative effect ... prior to World War I was incalculable", according to Caldwell.[122]

Through his concert initiatives at the Hanover Rooms Bennett introduced a variety of chamber music to London audiences. His championship also significantly changed British opinion of the music of JS Bach. His "promotion of Bach was a story of perseverance against a contemporary perception that Bach's music was ... too difficult to listen to."[123] Newspaper reviews of the chamber concerts in which he included the music of Bach would initially describe the music in terms such as "grandeur there is, but no beauty" (1847) or "somewhat antiquated ... [but] extremely interesting" (1854).[124] A significant turning point was the attendance of Prince Albert at Bennett's 1858 performance of the St. Matthew Passion.[109]

Bennett left a substantial music library, a large proportion of which is owned by his great-great-grandson Barry Sterndale Bennett (b. 1939) and is on deposit at the Bodleian Library in Oxford.[125] Of his total of some 130 compositions, about a quarter have been recorded for CD; among these are symphonies, overtures, piano concerti, chamber music, songs and piano solo music.[126] During his bicentenary year of 2016, several concerts and events dedicated to Bennett's works were performed, including concerts and seminars at the RAM.[127][128] From April 11 to April 15 2016 he was featured as 'Composer of the Week' on BBC Radio 3.[129]

Notes and references

Notes

- ↑ Bennett always treated the name "Sterndale" as a given name rather than part of his surname; after he was knighted he was known as "Sir Sterndale Bennett".[2] "Sterndale" was adopted into a double-barrelled surname by his descendants.[3]

- ↑ Although named 'Royal Academy' from the outset, it received its Royal Charter only in 1830. See the "History" page on the RAM website (accessed 23 December 2015).

- ↑ The School eventually emerged as the National Training School for Music (1876) which proved a precursor for the Royal College of Music (1883).[72]

- ↑ However, Bennett's son records that, as well as having given in 1856 the English premiere of Schumann's Paradise and the Peri, his father frequently played Schumann's Symphonic Studies and conducted his Second Symphony at a Philharmonic Society concert in 1864.[96]The Times was unenthusiastic about the work, but allowed that "Professor Bennett took infinite pains with the symphony; it was magnificently played and favourably received."[97]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Firman (2004)

- ↑ "Sir Sterndale Bennett", The Times, 2 February 1875, p. 9.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Temperley and Williamson (n.d.)

- ↑ Bennett (1907), p. 6.

- ↑ Bennett (1907), p. 18.

- ↑ Edwards (1903a), p. 306.

- ↑ Bennett (1907), p. 14.

- ↑ Bennett (1907), p. 15.

- ↑ Bennett (1907), p. 21.

- ↑ Bennett (1907), p. 27.

- ↑ Davison (1912), pp. 24–5.

- ↑ "The Royal Academy of Music", The Observer, 12 December 1830, p. 2.

- 1 2 Edwards (1903a) p. 307.

- ↑ Bennett (1907), pp. 27–28.

- 1 2 Bennett (1907), pp. 28–29.

- 1 2 Young (1967), p. 447.

- ↑ Bennett (1907), p. 35

- ↑ Bennett (1907), p. 36.

- ↑ Bennett (1907), p. 38.

- ↑ Davison (1912), p. 21.

- ↑ Anon, "Society of British Musicians", in Oxford Music Online (subscription required), accessed 21 December 2015

- ↑ Davison (1912), p. 24.

- 1 2 Bush (1986), p. 324.

- ↑ Williamson (1996), p. 30, p. 61.

- ↑ Young (1967), p. 448.

- ↑ Davison (1912), pp. 25–26.

- ↑ Temperley (1989a, p. 209.)

- ↑ Schumann (1988), pp. 116–118.

- ↑ Temperley (1989a), p. 214.

- ↑ Cited in Temperley (1989b), p. 12.

- ↑ Temperley (1989a), p. 208.

- ↑ Anon (1943)

- ↑ Bennett (1907), pp. 148—150.

- ↑ Squire (1885), p. 248.

- ↑ Bush (1965), p. 88.

- ↑ Schumann, p. 132.

- ↑ Bennett (1907), p. 162.

- ↑ "The Philharmonic Society", The Times, 13 June 1842, p. 5

- ↑ "Philharmonic Society", The Times, 11 June 1844, p. 5.

- ↑ Bennett (1907), p. 168.

- 1 2 Edwards (1903b), p. 380.

- ↑ Bennett (1907), pp. 209—214.

- 1 2 Stanford (1916), p. 641.

- ↑ Bennett (1907), pp. 189—192.

- ↑ Young (1967), p. 446.

- ↑ Young (1967), pp. 452—453.

- ↑ Parrott (2006), pp. 34–5.

- ↑ Parrott (2006), p.34, p. 36.

- ↑ The Norwood Review Vol 212 Spring 2016, pp. 12-15.

- ↑ French, Elizabeth (2007), "Bennett & Bache: Piano Concertos" (liner notes to Hyperion Records CD CDA67595), accessed 12 January 2016.

- ↑ Bennett (1907), pp. 224—5.

- 1 2 Edwards (1903b), p. 381.

- ↑ Stanford (1916), p.647.

- ↑ Temperley (1989a, p. 210.)

- ↑ Ehrlich (1995), p. 94.

- ↑ Ehrlich (1995), p. 102.

- ↑ Ehrlich (1995), p. 95.

- ↑ Ehrlich (1995), p. 97.

- ↑ Bennett (1907), p. 454; Ehrlich (1995), p. 105.

- ↑ Bennett (1907), pp. 314—317.

- ↑ Kent, Christopher. Journal of Royal College of Organists Vol 10 (2016) p.51.

- ↑ Bennett (1907), pp. 326—329.

- 1 2 3 Squire (1885)

- ↑ Bennett (1907), pp. 320.

- ↑ Bennett (1907), p. 350.

- ↑ Bennett (1907), p. 354.

- ↑ Stanford (1916), p. 655.

- ↑ Bennett (1907), pp. 369–370.

- ↑ Bennett (1907), pp. 372–375.

- ↑ Stanford (1916), p. 656.

- ↑ Bennett (1907), pp. 386—389.

- ↑ Rainbow (1980), p. 213.

- ↑ Bennett (1907), pp. 419—422.

- ↑ Wright (2005)

- ↑ Bennett (1907), p. 398; Wright (2005), pp. 238—9.

- ↑ Bennett (1907), pp. 399—405.

- ↑ Bennett (1907), p. 384.

- ↑ Bennett (1907), p. 418.

- ↑ "Sterndale Bennett Prize", Royal Academy of Music, accessed 5 March 2015

- ↑ Bennett (1907), p. 415.

- ↑ "Sir William Sterndale Bennett 1816–1875", Open Plaques, accessed 15 May 2012

- ↑ Bennett (1907), pp. 446—447.

- ↑ Edwards (1903c), p. 525.

- ↑ Foster (1913), pp. 347—349.

- ↑ Bennett (1907), p. 156.

- ↑ Foster (1913), p. 352.

- ↑ Bennett (1907)

- ↑ "Mr. R. Sterndale Bennett", The Times, 31 August 1963, p. 8

- ↑ "Joan Sterndale Bennett – Obituary", The Times, 30 April 1996

- ↑ "Sterndale Bennett, Ernest Gaskill", Canadian Theatre Encyclopedia, accessed 15 May 2012

- ↑ Stanford (1916), p. 631.

- ↑ Temperley (2006), p. 22.

- ↑ Bush (1965), p. 89.

- ↑ Stanford (1916), pp. 632–633.

- ↑ Findon (1904), p. 19

- ↑ Bennett (1907), pp. 342–343.

- ↑ "Philharmonic Concerts", The Times, 31 May 1864, p. 14.

- ↑ Temperley (2006), pp. 45—57, and p. 57 n. 1.

- ↑ Conway (2012), p. 102.

- ↑ Temperley (2006), p. 72.

- ↑ Temperley (2006), p. 73.

- ↑ Temperley (2006), p. 77.

- ↑ Caldwell (1999), p. 235.

- ↑ Temperley (1989a), pp. 216–218.

- ↑ Hadow, Henry. "Sterndale Bennett", The Times Literary Supplement, 9 January 1908, p. 13.

- 1 2 Young (1967), p. 451.

- ↑ Caldwell (1999), p. 219.

- ↑ Caldwell (1999), p. 220.

- 1 2 Bach (1862), " Preface" (p.(i))

- ↑ Parrott (2008), pp. 36—37

- ↑ Conway (2012), p. 190.

- ↑ Bach (n.d.)

- ↑ Temperley (2006)

- ↑ Bennett (1907), p. 154. (letter of 17 December 1843).

- 1 2 Bennett (1907), p. 86.

- ↑ Bennett (1907), p. 235.

- ↑ Davison (1912), pp. 305–10.

- ↑ "WSB 200" on David Owen Norris website, accessed 11 January 2016.

- ↑ Temperley (2006), p. 3.

- ↑ Sheppard (1928), p. viii.

- ↑ Dibble, Jeremy. "Parry, Sir Hubert", Dawes, Frank. "Matthay, Tobias", Mackerness, E D. " Cusins, Sir William", Temperley Nicholas. "Bache, Francis Edward", Grove Music Online, Oxford University Press, accessed 5 March 2015 (subscription required)

- ↑ Caldwell (1999), p. 225.

- ↑ Parrott (2008), p. 38.

- ↑ Cited in Parrott (2008), pp. 31—32.

- ↑ Williamson (1996), introduction, p. x.

- ↑ "WSB – Select Discography" on David Owen Norris website, accessed 12 January 2016.

- ↑ "William Sterndale Bennett 2016", on Olivia Sham website, accessed 11 January 2016.

- ↑ "Sterndale Bennett Performances" on David Owen Norris website, accessed 30 July 2017.

- ↑ "William Sterndale Bennett, BBC Radio 3 website, accessed 30 July 2017.

Sources

- Anon (1943). "Mendelssohn, Sterndale Bennett and the Reid Professorship: An Unpublished Letter". The Musical Times. 84 (1209): 351. JSTOR 920807. (subscription required)

- Bach, J S (n.d.). Bennett, William Sterndale, ed. Forty Eight Preludes & Fugues. Lamborne Cock, Hutchings. OCLC 500720012.

- Bach, J S (1862). Bennett, William Sterndale, ed. Grosse Passions-Musik. Helen Johnston (trans). London: Lamborne Cock, Hutchings. OCLC 181892334.

- Bennett, J R Sterndale (1907). The Life of William Sterndale Bennett. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. OCLC 63021710.

- Bush, Geoffrey (1965). "Sterndale Bennett: The Solo Piano Works". Proceedings of the Royal Musical Association. 91: 85–97. JSTOR 765967. doi:10.1093/jrma/91.1.85. (subscription required)

- Bush, Geoffrey (1986). "Sterndale Bennett and the Orchestra". The Musical Times. 127 (1719): 322–324. JSTOR 965069. doi:10.2307/965069. (subscription required)

- Caldwell, John (1999). The Oxford History of English Music. Volume II – From c. 1815 to the Present Day. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-816288-X.

- Conway, David (2012). Jewry in Music: Entry to the Profession from the Enlightenment to Richard Wagner. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-01538-8.

- Davison, Henry (1912). Music in the Victorian Era from Mendelssohn to Wagner: Being the memoirs of J. W. Davison, Forty Years Music Critic of "The Times". London: Wm. Reeves. OCLC 671571687.

- Edwards, Frederic George (1903a). "William Sterndale Bennett (1816–1875), Part 1 of 3". The Musical Times. 44 (723): 306–309. JSTOR 903335. (subscription required)

- Edwards, Frederic George (1903b). "William Sterndale Bennett (1816–1875), Part 2 of 3". The Musical Times. 44 (724): 379–381. JSTOR 903249. (subscription required)

- Edwards, Frederic George (1903c). "William Sterndale Bennett (1816–1875), Part 3 of 3". The Musical Times. 44 (726): 923–927. JSTOR 903956. (subscription required)

- Ehrlich, Cyril (1995). First Philharmonic. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 0-19-816232-4.

- Findon, B W (1904). Sir Arthur Sullivan – His Life and Music. London: J Nisbot. OCLC 669931942.

- Firman, Rosemary (2004). "Bennett, Sir William Sterndale (1816–1875)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/2131. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Foster, Myles Birket (1913). The Philharmonic Society of London 1813–1912. London: John Lane, The Bodley Head. OCLC 592671127.

- Parrott, Isabel (2008). "William Sterndale Bennett and the Bach Revival in Nineteenth-Century England". In Cowgill, Rachel; Rushton, Julian. Europe, Empire, and Spectacle in Nineteenth-Century British Music. Aldershot: Ashgate Publishing. pp. 29–44. ISBN 978-0-7546-5208-3.

- Rainbow, Bernarr (1980). "London, §7, 4 (v): Royal College of Music (RCM)". The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians. 11. London: Macmillan. pp. 213–214. ISBN 0-333-23111-2.

- Schumann, Clara (2013) [1913]. Litzmann, Berthold, ed. Clara Schumann – An Artist's Life, Based on Material Found in Diaries and Letters – Volume 2. Grace Hadow (trans). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-108-06415-6.

- Schumann, Robert (1988). Pleasants, Henry, ed. Schumann in music – a Selection from the Writings. New York: Dover Publications. ISBN 978-0-486-25748-8.

- Sheppard, Elizabeth (1928). Middleton, Jessie A., ed. Charles Auchester. London: J. M. Dent. OCLC 504071713.

-

Squire, William Barclay (1885). "Bennett, William Sterndale". In Stephen, Leslie. Dictionary of National Biography. 4. London: Smith, Elder & Co. pp. 247–251.

Squire, William Barclay (1885). "Bennett, William Sterndale". In Stephen, Leslie. Dictionary of National Biography. 4. London: Smith, Elder & Co. pp. 247–251. - Stanford, Charles Villiers (1916). "William Sterndale Bennett: 1816–1875". The Musical Quarterly. 2 (4): 628–657. JSTOR 737945. doi:10.1093/mq/ii.4.628. (free access)

- Temperley, Nicholas (1989a). "Schumann and Sterndale Bennett". 19th-Century Music. 12 (3 (Spring 1989)): 207–220. JSTOR 746502. (subscription required)

- Temperley, Nicholas (ed) (1989b). The Lost Chord. Bloomington, Indianapolis: Indiana University Press. ISBN 0-253-33518-3.

- Temperley, Nicholas (ed) (2006). Lectures on Musical Life – William Sterndale Bennett. Woodbridge: Boydell Press. ISBN 978-1-84383-272-0.

- Temperley, Nicholas; Williamson, Rosemary (n.d.). "Bennett, Sir William Sterndale". Grove Music Online. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Retrieved 26 December 2015.(subscription required)

- Williamson, Rosemary (1996). Sterndale Bennett – A Descriptive Thematic Catalogue. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0-19-816438-8.

- Wright, David (2005). "The South Kensington Music Schools and the Development of the British Conservatoire in the Late Nineteenth Century". Journal of the Royal Musical Association. 130 (2): 236–282. JSTOR 3557473. doi:10.1093/jrma/fki012. (subscription required)

- Young, Percy M. (1967). A History of British Music. London: Ernest Benn. OCLC 654617477.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to William Sterndale Bennett. |

- Free scores by William Sterndale Bennett at the International Music Score Library Project (IMSLP)

- Selected pieces for pianoforte (From the Sibley Music Library Digital Score Collection)

- "WSB 200", celebrating Bennett's bicentenary, includes details of events.

- Free scores by William Sterndale Bennett in the Choral Public Domain Library (ChoralWiki)