George Gilbert Scott

| Sir George Gilbert Scott | |

|---|---|

Sir George Gilbert Scott | |

| Born |

13 July 1811 Parsonage, Gawcott, Buckinghamshire |

| Died |

27 March 1878 (aged 66) 39 Courtfield Gardens, South Kensington, London |

| Occupation | Architect |

| Awards | Royal Gold Medal (1859) |

| Buildings |

Wakefield Cathedral Albert Memorial Foreign and Commonwealth Office Midland Grand Hotel, St Pancras railway station Main building of the University of Glasgow St Mary's Cathedral, Glasgow St Mary's Cathedral, Edinburgh (Episcopal) King's College London Chapel |

Sir George Gilbert Scott RA (13 July 1811 – 27 March 1878), styled Sir Gilbert Scott, was a prolific English Gothic revival architect, chiefly associated with the design, building and renovation of churches and cathedrals, although he started his career as a leading designer of workhouses. Over 800 buildings were designed or altered by him.[1]

Scott was the architect of many iconic buildings, including the Midland Grand Hotel at St Pancras Station, the Albert Memorial, and the Foreign and Commonwealth Office, all in London, St Mary's Cathedral, Glasgow, the main building of the University of Glasgow, St Mary's Cathedral in Edinburgh and King's College London Chapel.

Life and career

Born in Gawcott, Buckingham, Buckinghamshire, Scott was the son of a cleric and grandson of the biblical commentator Thomas Scott. He studied architecture as a pupil of James Edmeston and, from 1832 to 1834, worked as an assistant to Henry Roberts. He also worked as an assistant for his friend, Sampson Kempthorne, who specialised in the design of workhouses,[2] a field in which Scott was to begin his independent career.[3]

Early work

Scott's first work was built in 1833. It was a vicarage for his father, a clergyman, in the village of Wappenham, Northamptonshire. It replaced the previous vicarage occupied by other relatives of Scott. Scott went on to design several other buildings in the village.

In about 1835, Scott took on William Bonython Moffatt as his assistant and later (1838–1845) as his partner. Over ten years or so, Scott and Moffatt designed more than forty workhouses, during the boom in building such institutions brought about by the Poor Law of 1834.[3] In 1837 they built the Parish Church of St John in Wall, Staffordshire. At Reading, they built the prison (1841–42) in a picturesque, castellated style.[4] Scott's first church, St Nicholas', was built at Lincoln, after winning a competition in 1838.[3] With Moffat he built the Neo-Norman church of St Peter at Norbiton, Surrey (1841).[5]

Gothic Revival

Meanwhile, he was inspired by Augustus Pugin to participate in the Gothic revival.[3] While still in partnership with Moffat.[6] he designed the Martyrs' Memorial on St Giles', Oxford (1841),[7] and St Giles' Church, Camberwell (1844), both of which helped establish his reputation within the movement.

Commemorating three Protestants burnt during the reign of Queen Mary, the Martyrs' Memorial was intended as a rebuke to those very high church tendencies which had been instrumental in promoting the new authentic approach to Gothic architecture.[8] St Giles', was in plan, with its long chancel, of the type advocated by the Ecclesiological Society: Charles Locke Eastlake said that "in the neighbourhood of London no church of its time was considered in purer style or more orthodox in its arrangement".[9] It did, however, like many churches of the time, incorporate wooden galleries, not used in medieval churches[10] and highly disapproved of by the high church ecclesiological movement.

In 1844 he received the commission to rebuild the Nikolaikirche in Hamburg (completed 1863), following an international competition.[11] Scott's design had originally been placed third in the competition, the winner being one in a Florentine inspired style by Gottfried Semper, but the decision was overturned by a faction who favoured a Gothic design.[12] Scott's entry had been the only design in the Gothic style.[3]

In 1854 he remodelled the Camden Chapel in Camberwell, a project in which the critic John Ruskin took a close interest and made many suggestions. He added an apse, in a Byzantine style, integrating it to the existing plain structure by substituting a waggon roof for the existing flat ceiling.[13]

Scott was appointed architect to Westminster Abbey in 1849. In 1853 he built a Gothic terraced block adjoining the abbey in Broad Sanctuary. In 1858 he designed Christchurch Cathedral, Christchurch, New Zealand which now lies partly ruined following the earthquake in 2011 and subsequent attempts to demolish the cathedral by the Anglican Church authorities. Demolition was blocked after appeals by the population of Christchurch but the future of this historic building is still in dispute [14][11]

The choir stalls at Lancing College in Sussex, which Scott designed with Walter Tower, were among many examples of his work that incorporated green men.[15]

Later, Scott went beyond copying mediaeval English gothic for his Victorian Gothic or Gothic Revival buildings, and began to introduce features from other styles and European countries as evidenced in his Midland red-brick construction, the Midland Grand Hotel at London's St Pancras Station, from which approach Scott believed a new style might emerge.

Between 1864 and 1876, the Albert Memorial, designed by Scott, was constructed in Hyde Park. It was a commission on behalf of Queen Victoria in memory of her husband, Prince Albert.

Scott advocated the use of Gothic architecture for secular buildings, rejecting what he called "the absurd supposition that Gothic architecture is exclusively and intrinsically ecclesiastical."[10] He was the winner of a competition to design new buildings in Whitehall to house the Foreign Office and War Office. Before work began, however, the administration which had approved his plans went out of office. Palmerston, the new Prime Minister, objected to Scott's use of the Gothic, and the architect, after some resistance drew up new plans in a more acceptable style.[16]

Honours

Scott was awarded the RIBA's Royal Gold Medal in 1859. He was appointed an Honorary Liveryman of the Turners' Company and in 1872, he was knighted. He died in 1878 and is buried in Westminster Abbey.

A London County Council blue plaque marks Scott's residence at the Admiral's House on Admiral's Walk in Hampstead.[17][18]

Family

Scott married Caroline Oldrid of Boston in 1838. Two of his sons George Gilbert Scott, Jr. and John Oldrid Scott, and his grandson Giles Gilbert Scott, were also prominent architects.[19] His third son, photographer, Albert Henry Scott (1844–65) died at the age of twenty-one. George Gilbert designed his funerary monument in St Peter's Church, Petersham.[20] His fifth and youngest son was the botanist Dukinfield Henry Scott.[21] He was also great-uncle of the architect Elisabeth Scott.[22]

Pupils

Scott's success attracted a large number of pupils, many would go on to have successful careers of their own, not always as architects. In the following list, the year next to the pupil's name denotes their time in Scott's office, some of the more famous were: Hubert Austin (1868), Joseph Maltby Bignell (1859–78), George Frederick Bodley (1845–56), Charles Buckeridge (1856–57), Somers Clarke (1865), William Henry Crossland (dates uncertain), C. Hodgson Fowler (1856–60), Thomas Gardner (1856–61), Thomas Graham Jackson (1858–61), John T. Micklethwaite (1862–69), Benjamin Mountfort (1841–46), John Norton (1870–78), George Gilbert Scott, Jr. (1856–63), John Oldrid Scott (1858–78), J. J. Stevenson (1858–60), George Henry Stokes (1843–47), George Edmund Street (1844–49), William White (1845–47).

Books

- Remarks on secular & domestic architecture, present & future. London: John Murray. 1857.

- A Plea for the Faithful Restoration of our Ancient Churches. Oxford: James Parker. 1859.

- Gleanings from Westminster Abbey / by George Gilbert Scott, with Appendices Supplying Further Particulars, and Completing the History of the Abbey Buildings, by W. Burges (2nd enlarged ed.). Oxford: John Henry and James Parker. 1863 [1861].

- Personal and Professional Recollections. London: Sampson Low & Co. 1879.

- Lectures on the Rise and Development of Medieval Architecture. I. London: John Murray. 1879.

- Lectures on the Rise and Development of Medieval Architecture. II. London: John Murray. 1879. online texts for vols. I & II

Additionally he wrote over forty pamphlets and reports. As well as publishing articles, letters, lectures and reports in The Builder, The Ecclesiologist, The Building News, The British Architect, The Civil Engineer's and Architect's Journal, The Illustrated London News, The Times and Transactions of the Royal Institute of British Architects.

Architectural work

His projects include:

Public buildings

- Workhouse in Winslow, Buckinghamshire (1835)

- Workhouses (1836) in: Amesbury, Wiltshire; Buckingham, Buckinghamshire; Kettering, Northamptonshire; Northampton, Northamptonshire; Oundle, Northamptonshire; Tiverton, Devon; Totnes, Devon; Towcester, Northamptonshire

- Workhouse in Guildford, Surrey (1836–38)

- Workhouses (1837) in: Bideford, Devon; Boston, Lincolnshire; Clutton, Somerset; Flax Bourton, Somerset; Gloucester, Gloucestershire; Liskeard, Cornwall; Newton Abbot, Devon; Hundleby, Lincolnshire; Tavistock, Devon

- The workhouse in Loughborough, Leicestershire (1837–38)

- Workhouses (1838) in: Amersham, Buckinghamshire;[23] Belper, Derbyshire; Great Dunmow, Essex; Lichfield, Staffordshire; Mere, Wiltshire; Penzance, Cornwall; Redruth, Cornwall

- Workhouse (1838) ; Williton, Somerset[24] and 'sister design' Witham, Essex

- Workhouses (1839) in: Billericay, Essex; Bedworth, Warwickshire; Edmonton, London; Louth, Lincolnshire; Newcastle-under-Lyme, Staffordshire; Old Windsor, Berkshire; St Austell, Cornwall; Uttoxeter, Staffordshire

- Buckingham Gaol extension and alterations (1839) in: Buckingham, Buckinghamshire

- The workhouse in Lutterworth, Leicestershire (1839–40)

- School and Master's House, Hartshill, Stoke on Trent (1840)

- Infant Orphan Asylum, Wanstead, Essex (1841–43)

- Martyrs' Memorial, Oxford (1841–43)

- Reading Gaol, Berkshire (1842–44)

- Lunatic Asylum, Shelton, Shropshire (1843)

- The workhouse, Macclesfield, Cheshire (1843)

- Lunatic Asylum, Clifton, York (1845)

- Lunatic Asylum, Wells, Somerset (1845)

- Astbury School and Masters House Congleton (1848)

- Christ Church School, Alsager, Cheshire (1848)[25]

- Brighton College, Sussex (1848–1866)

- Sandbach School, Sandbach, Cheshire (1849)

- School, Trefnant, Denbighshire (c. 1855)

- School, Tysoe, Warwickshire (1856)

- Literary Institution, Sandbach (1857)[26]

- Crimea War Memorial, Westminster School, Broad Sanctuary, Westminster (1858)

- School, Ashley, Northamptonshire (1858)

- The Vaughan Library, Harrow School, Middlesex (1861–63)

- Foreign and Commonwealth Office, Whitehall, London (1861–1868)

- Preston Town Hall, Lancashire (1862–67), destroyed by fire in 1947

- Old Schools, Cambridge (1864–67)

- Leeds General Infirmary (1864–67)

- the Albert Memorial, London (1864–72); in the podium frieze, one of the images of architects, sculpted by John Birnie Philip shows Scott himself.

- Midland Grand Hotel, St Pancras Station, London (1865)

- McManus Galleries – formerly the Albert Institute, Dundee (1865–69)

- The School, Great Dunmow, Essex (1866)

- Brill Swimming Baths, Brighton (1866–69) demolished 1929

Panoramic view of Brill's swimming bath, Brighton. Lithograph by J. Drayton Wyatt

Panoramic view of Brill's swimming bath, Brighton. Lithograph by J. Drayton Wyatt - Clifton Hampden Bridge, Oxfordshire (1867)

- Hall Cross School's library in Doncaster (1868)

- Market Cross, Helmsley, Yorkshire (1869)

- School Nocton, Lincolnshire (1869)

- Extension Radcliffe Infirmary, Oxford (1869–71)

- Cemetery Chapel, Ramsgate, Kent (1869–1872)[27]

- Lincoln's Inn, London, Library extension (1870–72), New Chambers Block A (1873) and New Chambers Block B (1876–78)

- the main building of the new campus of the University of Glasgow (1870), often called the "Gilbert Scott Building"

- Savernake Hospital, Wiltshire (1871–72)

- Gatehouse to Ramsgate Cemetery, Kent (1872)[28]

- The University Senate Hall, Bombay University (1869–74)

- The University Library and Rajabai Clock Tower, Bombay University (1869–78)

- The Clarkson Memorial in Wisbech. Scott first put forward designs in 1875, but work did not start until 1880. The eventual design was a slightly altered version of Scott's original design.

Domestic buildings

- Vicarage, Wappenham, Northamptonshire (1833)

- 16 High Street, Chesham, Buckinghamshire (1835)

- Vicarage, Dinton, Buckinghamshire (1836)

- Rectory, Weston Turville, Buckinghamshire (1838)

- Parsonage, Blakesley, Northamptonshire (1839)

- Parsonage, Hartshill, Stoke on Trent (1840)

- Seaman's Houses, Whitby, Yorkshire (1842)

- Rectory, Teffont Evias, Wiltshire (1842)

- Workers Houses, Hartshill, Stoke on Trent (1842–48)

- Parsonage, Clifton Hampden, Oxfordshire (1843–46)

- Parsonage, Barnet, Hertford (1845)

- Parsonage, St. Mark's, Swindon (c. 1846)

- Parsonage, Wembley, Middlesex (1846)

- Parsonage, Weeton, North Yorkshire (c. 1852)

- Houses Broad Sanctuary, Westminster (1852–54)

- Parsonage, Trefnant, Denbighshire (c. 1855)

- Parsonage, St. Mary's, Stoke Newington, London (c. 1855)

- All Souls' Vicarage, Halifax, Yorkshire (c. 1856)

- Cottages, Ilam, Staffordshire (c. 1857)

- Almshouses, Hartshill, Stoke on Trent (1857)

- Lanhydrock House, near Bodmin, Cornwall (1857) an Elizabethan mansion rebuilt after a fire, formal gardens assisted by Richard Coad

- Parsonage, Kilkhampton, Cornwall (c. 1858)

- Walton Hall, Warwickshire (1858)

- Treverbyn Vean, St Neot, Cornwall (1858–62)

- Parsonage, Ashley, Northamptonshire (1858)

- Parsonage, Bridge, Kent (c. 1859)

- Vicarage, Ranmore Common, Surrey (c. 1859)

- Kelham Hall, Nottinghamshire (1859–62)

- Workers' housing at Akroydon, Halifax (1859)

- Almshouses, Sandbach (1860)[29]

- Lee Priory, Littlebourne, Kent, alterations and additions (1860–63) demolished

- Rectory, Higham, Forest Heath, Suffolk (c. 1861)

- Kingston Grange, Kingston St Mary, Somerset for Mr Perkins (c. 1861)

- Parsonage, St. Andrew's, Leicester (c. 1861)

- Hartland Abbey (c.1851) supervised by Richard Coad, built by Pulsman of Barnstaple

- Hafodunos, Llangernyw, North Wales (1861–1866)

- Vicarage, Jarrom Street, Leicester (1862)[30]

- Nos 1,3 & 3a Dean's Yard, Westminster (1862)

- Parsonage, Leith, Midlothian (1862)

- Brownsover Hall, Warwickshire, date uncertain (c. 1860)

- Two lodge houses at Great Barr Hall, near Birmingham (pre-1863)

- The Master's House, St John's College, Cambridge (1863)

- Parsonage, Christ Church, Ottershaw, Surrey (c. 1864)

- Parsonage, St. Luke's, Weaste, Lancashire (c. 1865)

- Schools Master's House, Ashley, Northamptonshire (1865)

- Almshouses, Winchcombe, Gloucestershire (1865)

- Rectory, Tydd St Giles, Cambridgeshire (1868)

- Vicarage, Higham Green, Suffolk

- Parsonage, Mirfield, Yorkshire (1869)

- Polwhele House, Truro, Cornwall, additions (c. 1870)

- Vicarage, Hillesden, Buckinghamshire (1871)

- St Mary's Homes, Godstone (1872)

- Scott's Building, King's College, Cambridge (1873)

- Parsonage, St. Michael's, New Southgate, Middlesex (c. 1874)

- Parsonage, St. Saviour's, Leicester (1875)

- Parsonage, Fulney, Lincolnshire (1877–80)

- New Court, Pembroke College, Cambridge (1881)

- Wanstead Infant Orphanage Asylum, London Borough of Redbridge (1841)

Church buildings

- St Mark's Church, Ladywood (1840–41) (demolished 1947)

- St Giles' Church, Camberwell, London (1841–44)

- Christ Church, Bridlington (1840–41)

- St Mary's Church, Hanwell, Middlesex (1841)[31]

- Holy Trinity, Hulme (1841)

- St Mary's Church, Mirfield (1841)

- Holy Trinity Church, Hartshill, Stoke on Trent (1842)

- St John the Baptist's Church, St John's, Woking, Surrey (1842)

- St. John the Baptist Church, Beeston, Nottinghamshire (1842)

- St Peter's Church, Norbiton, Surrey (1842)

- St. John the Baptist's Church, Leenside, Nottingham (1843–44)

- Holy Trinity Church, Halstead, Essex (1843–44)

- St John the Evangelist, West Meon, Hampshire (1843–46), squared knapped flint work

- St Mark's Church, Worsley, Greater Manchester (1844–46)

- St Matthias, Malvern Link, Worcestershire (1844–46) [32]

- St Mark's Church, Swindon, (1845)

- St Nikolai, Hamburg (1845–80), the tallest building in the world from 1874 to 1876.

- The Cathedral of St John the Baptist in St John's, Newfoundland (1847, construction overseen by apprentice William Hay)

- St. Mary the Virgin, Aylesbury (1848)

- St Gregory's Church, Canterbury (1848)

- St Paul's Church, Canterbury (1848)

- St Cwyfan, Tudweiliog, Gwynedd (1849)

- St Peter's Church, South Croydon (1851)

- Emmanuel Church, Forest Gate, London (1852)

- St John's Church, Eastnor, Herefordshire Church (1852) and Monument (1855)[33]

- All Saints Church, Watford, Hertfordshire (1853)

- St Paul's Episcopal Cathedral, Dundee (1853)(Cathedral since 1905)

- All Saints Church, Sherbourne, Warwick (1854)[34]

- Christ Church, Lee Park, Kent (1854) (bombed 1941, demolished 1944)

- St John the Evangelist, Shirley, Surrey (1854)

- Holy Trinity Church, Coventry (1854)

- Chapel of Exeter College, Oxford (1854–60)

- St John's Church, Bilton, Harrogate (1855)

- St Mary, Hayes, Kent (alterations) (1856–62)

- St Peter, Bushley, Worcestershire. Roof (1856)[35]

- St Mary, Tedstone Delamere, Herefordshire Chancel (1856–57)[36]

- St George's Minster, Doncaster (1858)

- St Mary New Church, Stoke Newington (1858)[37]

- St Matthias Church, Richmond, London (1858)

- All Souls Church, Halifax (1859)

- St. Thomas's Church, Huddersfield (1859)

- St Michael and All Angels Church, Leafield, Oxfordshire (1859–60)[38]

- St Matthew's Church, Stretton, Cheshire (1859 and 1867)

- St Matthew's Church. Yiewsley, Hillingdon (1859)

- St Mary, Edvin Loach, Herefordshire (?1860)[39]

- Christ Church, Wanstead, Essex (1861)

- St Stephen's Church, Higham Green, Suffolk (1861)

- St. John the Evangelist, Sandbach Heath (1861)[40]

- St Andrews, Jarrom Street, Leicester (1862)[41][42][43]

- The Hereford Screen (1862), choir screen from Hereford Cathedral, now restored and in the Victoria and Albert Museum, London

- Chapel of Wellington College, Berkshire (1861-3)[44]

- All Saints Church, Langton Green, Kent (1862–63)[45]

- St Andrew's Hospital Chapel, Northampton (1863)

- St Andrew's Church, Derby (1864-67)[46]

- St Andrew's Church, Uxbridge (1865)

- St John the Baptist, Penshurst (1865)

- St Luke's Church, Pendleton (1865)[47]

- St Stephen & St Mark, Lewisham (1865) [48]

- St Mary's Church, Shackleford, Surrey (1865)

- St Denys Church, Southampton (1868)

- St Stephen's Church, Higham Green, Suffolk (1868)

- St James' Church, Cradley, Herefordshire Chancel (1868)[49]

- St Peter's Church, Edensor, Derbyshire (1867–70)

- All Saints church, Ryde, Isle of Wight (1872)

- St. Thomas of Canterbury Church, Chester (1872)[50]

- St Peter and St Paul, Priory Church Leominster, Herefordshire Quatrefoil piers (1872–79).[51]

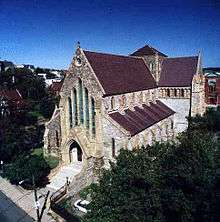

- The Cathedral Church of St Mary the Virgin, Glasgow (1873)[52]

- Christ Church, Bradford-on-Avon (additions) (1875)

- St Saviour's Church, Leicester (1875–77)

- All Souls, Blackman Lane, Leeds (1879) – his last work, a large lancet-style church

- St Mary The Virgin, Speldhurst Kent (1879)

- St. Michael and St. George Cathedral, Grahamstown (tower and spire completed in 1879)

- St Paul's Church, Low Fulney, Spalding, Lincolnshire (completed 1880)[53]

- ChristChurch Cathedral, Christchurch, New Zealand

- St John The Baptist Church, Busbridge, Godalming, Surrey

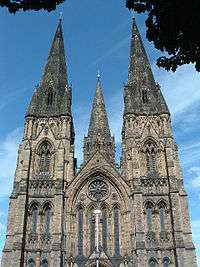

- St Mary's Cathedral, Edinburgh (Episcopal)

- St Mary's Church, Mirfield, West Yorkshire

- St Mary, Timsbury, Somerset[54]

- St Michael, Stourport-on-Severn, Worcestershire designed (1875) started (1881) by son John Oldrid Scott, never finished and partly demolished.[55]

- St Nicholas's, Newport, Lincoln, Lincolnshire.

- St Peter's Church, Elworth, Cheshire.

- Christ The Saviour, Ealing, London

- Christ Church, Ramsgate, Kent

- Christ Church, Swindon, Wiltshire

- Ramsgate Cemetery Chapel, Kent (1869)[56]

Restorations

Churches

Scott was involved in major restorations of medieval church architecture, all across England.

- Chantry Chapel of St Mary the Virgin, Wakefield, West Yorkshire (1842)

- Church of St Mary and All Saints, Chesterfield, Derbyshire (1843)

- St Mary's Church, Sandbach (1847)[57]

- St. Mary's Church, Temple Balsall, Solihull, West Midlands (1849)

- St. John the Baptist Church, Glastonbury, Somerset (1850s)

- St. Mary's Church, Nottingham, Nottinghamshire (1850s)

- Church of St Editha, Tamworth, Staffordshire (1850s)

- Church of St. Mary Magdalene, Newark-on-Trent, Nottinghamshire (1850s)

- All Saints' Church, Oakham (1857–1858)

- St John the Baptist Church, Aconbury, Herefordshire (1863)[58]

- St Paul (Without the Walls) Church, Canterbury, Kent (1860s)

- Church of St John the Baptist, Bromsgrove, Worcestershire (1858)[59]

- St Many Magdelene, Duns Tew, Oxfordshire (1861–62)

- St Helen's Church, Welton, East Riding of Yorkshire (1862–63)

- St Peter and St Paul, Buckingham Church Buckingham, (1862–1878), additions to the original 1780 church including chancel, buttresses, porch, roof and nave alterations. Work continued over the years by his second son John Oldrid Scott and grandson Charles Marriott Oldrid Scott.[60]

- St John the Baptist Church, Upton Bishop, Herefordshire (1862)[61]

- St Leonard, Yarpole, Herefordshire, restoration of chancel(1864)[62]

- St Wulfram's Church, Grantham, Lincolnshire (1866–75)

- St Mary Abbots, Kensington, London (1872)

- All Saints' Church, Hillesden Buckinghamshire (1874–75)

- St. Margaret's Church, King's Lynn (1875)

- St. Margaret's, Westminster, London (1877–78)

- St Mary's Island church on the Orchardleigh Estate, Somerset (1878)[63]

- St Peter's Church, Prestbury, Cheshire (1879–1881)

- St Barnabas' Church, Bromborough, Merseyside (1862-1864)

- St Andrews Parish Church, Spratton, Northamptonshire

- Church of St Mary the Less, Cambridge, Cambridgeshire

Cathedrals

- Ely Cathedral (1847–78)

- Gloucester Cathedral (1854–76)

- Peterborough Cathedral (1855–60)

- Coventry Cathedral (1855–57)

- Hereford Cathedral east side (1855–63)

- Lichfield Cathedral (1855–61 & 1877–81)

- Wakefield Cathedral (1858–60, 1865–69 and 1872–74)

- Durham Cathedral (1859 and 1874–76)

- Brecon Cathedral (1860–62 & 1872–75)

- Canterbury Cathedral (1860 & 1877–80)

- Chichester Cathedral (1861–67 & 1872)

- Ripon Cathedral (1862–72)

- St Edmundsbury Cathedral (1863–64 & 1867–69)

- Worcester Cathedral (1863–64, 1868 & 1874)

- St David's Cathedral, St Davids, Wales (1864–76)

- Salisbury Cathedral (1865–71)

- St Asaph Cathedral (1866–69 & 1871)

- Newcastle Cathedral (1867–71 & 1872–76)

- Chester Cathedral (1868–75)

- Exeter Cathedral (1869–70)

- Christ Church, Oxford east wall of choir (1870–72 & 1874–76)

- Rochester Cathedral (1871–74)

- St Albans Cathedral (1871–80)

- Manchester Cathedral (c. 1872)

- Winchester Cathedral (1875)

Additionally Scott designed the Mason and Dixon monument in York Minster (1860), prepared plans for the restoration of Bristol Cathedral in 1859 and Norwich Cathedral in 1860 neither of which resulted in a commission, and designed a pulpit for Lincoln Cathedral in 1863.

Abbeys, priories and collegiate churches

- St Mary's Church, Stafford, 1842–45

- Beverley Minster 1844, 1866–68, 1877

- Westminster Abbey, 1848–78

- Dorchester Abbey, 1858, 1862, 1874

- King's College, Cambridge, 1859–63, 1875

- Bath Abbey, 1860–77

- Pershore Abbey, 1861–64, 1867

- St. George's Chapel, Windsor Castle, 1863

- Great Malvern Priory, c. 1864

- Boxgrove Priory, 1864–67

- Priory Church, Leominster, 1864–66, 1876–78

- Monkwearmouth-Jarrow Abbey, 1865–66

- Selby Abbey, 1872–74

- Tewkesbury Abbey, 1874–79

- Bridlington Priory, 1875–80

Other restoration work

Scott restored the Inner Gateway (also known as the Abbey Gateway) of Reading Abbey in 1860 – 1861 after its partial collapse.[64] St Mary's of Charity in Faversham, which was restored (and transformed, with an unusual spire and unexpected interior) by Scott in 1874, and Dundee Parish Church, and designed the chapels of Exeter College, Oxford, St John's College, Cambridge and King's College London. He also designed St Paul's Cathedral, Dundee.

Lichfield Cathedral's ornate West Front was extensively renovated by Scott from 1855 to 1878. He restored the cathedral to the form he believed it took in the Middle Ages, working with original materials where possible and creating imitations when the originals were not available. It is recognised as some of his finest work.

Gallery of architectural work

Work house, Louth Lincolnshire (1839)

Work house, Louth Lincolnshire (1839) St. Mary's Hanwell, Middlesex (1841)

St. Mary's Hanwell, Middlesex (1841) East end, St. Mary's Hanwell, Middlesex (1841)

East end, St. Mary's Hanwell, Middlesex (1841) Martyrs' Memorial, Oxford (1841–43)

Martyrs' Memorial, Oxford (1841–43)- St. Giles Church, Camberwell (1842–44)

- Reading Gaol, Berkshire (1842–44)

Holy Trinity Church, Halstead, Essex (1843–44)

Holy Trinity Church, Halstead, Essex (1843–44) St Martin's Zeal, Wiltshire (1845–46)

St Martin's Zeal, Wiltshire (1845–46) Nikolaikirche, Hamburg, Germany (1845–80), bombed during World War II and now a ruin

Nikolaikirche, Hamburg, Germany (1845–80), bombed during World War II and now a ruin Cathedral of St.John's, Newfoundland, Canada (1847-1905)

Cathedral of St.John's, Newfoundland, Canada (1847-1905) Cathedral of St.John's, Newfoundland, Canada (1847-1905)

Cathedral of St.John's, Newfoundland, Canada (1847-1905) St. Peter's Church, Croydon (1849–51)

St. Peter's Church, Croydon (1849–51) St. Anne's Alderney (c.1850)

St. Anne's Alderney (c.1850) St. Barnabas's Church, Weeton, North Yorkshire (1852)

St. Barnabas's Church, Weeton, North Yorkshire (1852)- St. George's Church, Doncaster, Yorkshire (1853–58)

St. George's Church, Doncaster, Yorkshire (1853–58)

St. George's Church, Doncaster, Yorkshire (1853–58) Lichfield Cathedral, as restored and with fittings by Scott (1855–61) & (1877–81)

Lichfield Cathedral, as restored and with fittings by Scott (1855–61) & (1877–81)- All Souls', Haley Hill, Halifax (1856–59)

Interior looking east, All Souls', Haley Hill, Halifax, Yorkshire (1856–59)

Interior looking east, All Souls', Haley Hill, Halifax, Yorkshire (1856–59) Cottages, Ilam, Staffordshire (c.1871)

Cottages, Ilam, Staffordshire (c.1871) Chapel door, Exeter College, Oxford (1857–59)

Chapel door, Exeter College, Oxford (1857–59) East end, Chapel, Exeter College, Oxford (1857–59)

East end, Chapel, Exeter College, Oxford (1857–59) Kelham Hall, Nottinghamshire (1858–62)

Kelham Hall, Nottinghamshire (1858–62) Crimea War Memorial, Westminster School, Broad Sanctuary, Westminster (1858)

Crimea War Memorial, Westminster School, Broad Sanctuary, Westminster (1858) Walton Hall, Warwickshire (c.1858-62)

Walton Hall, Warwickshire (c.1858-62) St. Mary's, Edwin Loach, Herefordshire (c.1859)

St. Mary's, Edwin Loach, Herefordshire (c.1859) The Chapel, Brighton College (1859)

The Chapel, Brighton College (1859) All Saints, Nocton (1860–63)

All Saints, Nocton (1860–63)- SS. Peter and Paul Church, Buckingham, heavily restored (1860–67)

Nave Vault, Bath Abbey (1860–77) (copy of the medieval vault in the chancel)

Nave Vault, Bath Abbey (1860–77) (copy of the medieval vault in the chancel) The Chapel, King's College London (1861–62)

The Chapel, King's College London (1861–62) Christ Church, Southgate, London (1861–62)

Christ Church, Southgate, London (1861–62) Vaughan Library, Harrow School, London (1861–63)

Vaughan Library, Harrow School, London (1861–63) Screen from Hereford Cathedral (1862) now in the Victoria and Albert Museum

Screen from Hereford Cathedral (1862) now in the Victoria and Albert Museum All Saints' Church, Sherbourne, Warwickshire (1862–64)

All Saints' Church, Sherbourne, Warwickshire (1862–64) Foreign and Commonwealth Office, London (1862–75)

Foreign and Commonwealth Office, London (1862–75) Foreign and Commonwealth Office, London (1862–75)

Foreign and Commonwealth Office, London (1862–75) Grand Staircase, Foreign and Commonwealth Office, London (1862–75)

Grand Staircase, Foreign and Commonwealth Office, London (1862–75) Ceiling, Grand Staircase, Foreign and Commonwealth Office, London (1862–75)

Ceiling, Grand Staircase, Foreign and Commonwealth Office, London (1862–75) Looking east, St. John's College Chapel, Cambridge (1863–69)

Looking east, St. John's College Chapel, Cambridge (1863–69)- Clifton Hampden Bridge, Oxfordshire (1864)

Leeds General Infirmary (1864–70)

Leeds General Infirmary (1864–70)- St. David's Cathedral, Pembrokeshire, showing Scott's west front (1864–76)

Albert Memorial, London (1864–76)

Albert Memorial, London (1864–76) Central ciborium, Albert Memorial, London (1864–76)

Central ciborium, Albert Memorial, London (1864–76) Christchurch Cathedral, Christchurch, New Zealand (1864-1904)

Christchurch Cathedral, Christchurch, New Zealand (1864-1904) St. Mary's Church, Norney, Shackleford, Surrey (1865)

St. Mary's Church, Norney, Shackleford, Surrey (1865) Former Albert Institute Dundee (1865–69)

Former Albert Institute Dundee (1865–69)- St Luke's church, Salford (1865)

Former Midland Grand Hotel, St. Pancras Station (1866–76)

Former Midland Grand Hotel, St. Pancras Station (1866–76) Roof scape, Former Midland Grand Hotel, St. Pancras Station (1866–76)

Roof scape, Former Midland Grand Hotel, St. Pancras Station (1866–76) Former Midland Grand Hotel, St. Pancras Station (1866–76)

Former Midland Grand Hotel, St. Pancras Station (1866–76)- Detail of decoration in the Train Shed, St. Pancras Station (1866–76)

Clock Tower, Former Midland Grand Hotel, St. Pancras Station (1866–76)

Clock Tower, Former Midland Grand Hotel, St. Pancras Station (1866–76)- Reredos high altar, Worcester Cathedral (1867–68)

University of Glasgow (1867–70), the spire was added after Scott's death by his son John Oldrid Scott

University of Glasgow (1867–70), the spire was added after Scott's death by his son John Oldrid Scott Highclere Church, Hampshire (1869–70)

Highclere Church, Hampshire (1869–70) Brownsover Hall, Warwickshire (c.1870)

Brownsover Hall, Warwickshire (c.1870) St Mary Abbots Church, Kensington (1870–72)

St Mary Abbots Church, Kensington (1870–72) Design for Reichstag, Berlin, not executed (1872)

Design for Reichstag, Berlin, not executed (1872)- Pulpit, Worcester Cathedral (1873–74)

West front, St. Mary's Cathedral, Edinburgh (1874–80)

West front, St. Mary's Cathedral, Edinburgh (1874–80) East front, St. Mary's Cathedral, Edinburgh (1874–80)

East front, St. Mary's Cathedral, Edinburgh (1874–80)- Grahamstown Cathedral, South Africa (1874–78) & finished (1893)

- Hall, Bombay University, India (1876)

- Clarkson Memorial, Wisbech, (1880–82)

New Court, Pembroke College, Cambridge (1881)

New Court, Pembroke College, Cambridge (1881) St Barnabas' Church, Bromborough, Merseyside (1862–64)

St Barnabas' Church, Bromborough, Merseyside (1862–64)

See also

References

- ↑ Cole, 1980, p. 1.

- ↑ "George Gilbert Scott (1811–1878) and William Bonython Moffatt (−1887)". The Workhouse. 23 April 2007. Archived from the original on 8 October 2007. Retrieved 29 April 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Bayley 1983, p.43

- ↑ Hitchcock 1977, p.146

- ↑ Cherry and Pevsner 1990, p.313

- ↑ Hitchcock 1977, p.152

- ↑ Eastlake 1872, p.219

- ↑ Whiting, R. C. (1993). Oxford Studies in the History of a University Town Since 1800. Manchester University Press. p. 56. ISBN 9780719030574. The terms of the commission had stipulated that it should be based on the Eleanor Cross at Waltham

- ↑ Eastlake 1872, p.220

- 1 2 Eastlake 1872, p.221

- 1 2 Hitchcock 1977, p.153

- ↑ Mallgrave, Harry Francis (2005). Modern Architectural Theory: A Historical Survey, 1673–1968. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521793063.

- ↑ Blanch, William Harnett (1875). Y parish of Camberwell. A brief account of the parish of Camberwell, its history and antiquities. G.W. Allen.

- ↑ http://restorechristchurchcathedral.co.nz/?p=515

- ↑ Hayman, Richard (April 2010). "Ballad of the Green Man". History Today. 60 (4).

- ↑ Eastlake 1872, pp.311– 2

- ↑ "SCOTT, SIR GEORGE GILBERT (1811–1878)". English Heritage. Retrieved 9 January 2012.

- ↑ "Sir George Gilbert Scott". Flickr.

- ↑ Allinson, Kenneth (24 September 2008). Architects and Architecture of London. Routledge. p. 164. ISBN 9781136429644.

- ↑ Historic England. "Tomb of Albert Henry Scott in the Churchyard of St Peter's Church (1380183)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 22 January 2016.

- ↑ Arber, Agnes; Goldbloom, Alexander. "Scott, Dukinfield Henry". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/35984. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ↑ Stamp, Gavin (2004). "Scott, Elisabeth Whitworth (1898–1972), architect". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/24869. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ↑

- ↑

- ↑ Sutton, James C, ed. (1999). Alsager the Place and its People. Alsager: Alsager History Research Group. p. not cited. ISBN 0-9536363-0-5.

- ↑ John Parsons Earwaker, "The History of the Ancient Parish of Sandbach", 1890, (page 86)

- ↑ "Cemetery Chapels, Ramsgate". www.britishlistedbuildings.co.uk. Retrieved 21 February 2014.

- ↑ "Gate House to Cemetery About 50 Metres South of Cemetery Chapel, with Side Walls, Ramsgate". www.britishlistedbuildings.co.uk. Retrieved 21 February 2014.

- ↑ "Sandbach Almshouses Foundation Plaque", Wikipedia Commons

- ↑ "Vicarage, Jarrom Street". Flickr.

- ↑ Reynolds, Susan, ed. (1962). A History of the County of Middlesex: Volume 3: Shepperton, Staines, Stanwell, Sunbury, Teddington, Heston and Isleworth, Twickenham, Cowley, Cranford, West Drayton, Greenford, Hanwell, Harefield and Harlington. Victoria County History. pp. 230–33. Retrieved 21 July 2007.

- ↑ Bridges, Tim (2005). Churches of Worcestershire (2nd ed.). Logaston Press. p. 157. ISBN 1-904396-39-9.

- ↑ Pevsner, 1963, pages 122–123

- ↑ "Sherbourne Park -". sherbournepark.com.

- ↑ Pevsner, 1968, page 113

- ↑ Pevsner, 1963, page 299

- ↑ Weinreb, Ben, and Hibbert, Christopher (1992). The London Encyclopaedia (reprint ed.). Macmillan. p. 610.

- ↑ Sherwood & Pevsner, 1974, page 682

- ↑ Pevsner, 1963, page 126

- ↑ John Parsons Earwaker, "The History of the Ancient Parish of Sandbach", 1890, (page 87)

- ↑ "Leicester St Andrew - Learn - FamilySearch.org". familysearch.org.

- ↑ "Error". leicester.gov.uk.

- ↑ http://www.kairos-press.co.uk/html/a_church_on_jarrom_street__st_.html

- ↑ "Chapel At Wellington College With Porch Colonnade And Gateway Adjoining West End". Historic England. Retrieved 24 April 2017.

- ↑ Historic England. "Details from listed building database (1240546)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 23 March 2012.

- ↑ "St Andrew’s Church, London Road, Litchurch". Derby Mercury. England. 30 March 1864. Retrieved 4 June 2017 – via British Newspaper Archive. (Subscription required (help)).

- ↑ Historic England. "Details from listed building database (1386145)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 3 September 2014.

- ↑ "Lewisham, St Stephen with St Mark - East Lewisham Deanery - The Diocese of Southwark". anglican.org.

- ↑ Pevsner, 1963, page 106

- ↑ A short history of our church building by Ian Thomas (Parish Magazine September 2010)

- ↑ Pevsner, 1963, page 226

- ↑ "St Mary's Episcopal Cathedral Glasgow". Glasgow Architecture. Retrieved 31 August 2012.

- ↑ visit Ayscoughfee Hall Museum, Spalding for further information

- ↑ "Church of St. Mary the Virgin". Images of England. Retrieved 29 September 2007.

- ↑ Pevsner, 1968, page 271

- ↑ "Cemetery Chapels, Ramsgate". www.britishlistedbuildings.co.uk. Retrieved 15 April 2013.

- ↑ John Parsons Earwaker, "The History of the Ancient Parish of Sandbach", 1890, (page 28)

- ↑ Pevsner, 1963, page 63

- ↑ Pevsner, 1968, page 109

- ↑ Clarke, John (1984). The Book of Buckingham. Buckingham: Barracuda Books. p. 145. ISBN 0-86023-072-4.

- ↑ Pevsner, 1963, page 304

- ↑ Pevsner, 1963, page 327

- ↑ "Church of St. Mary, causeway bridge, and gates". Images of England. Retrieved 20 November 2007.

- ↑ Tyack, Bradley and Pevsner, Geoffrey, Simon and Nikolaus (2010). The Buildings of England: Berkshire. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. p. 443. ISBN 978-0-300-12662-4.

Sources

- Bayley, Stephen (1983). The Albert Memorial (paperback ed.). London: Scolar Press.

- Cole, David (1980). The Work of Gilbert Scott. London: Architectural Press. ISBN 0-85139-723-9.

- Eastlake, Charles Locke (1872). A History of the Gothic Revival. London: Longmans, Green & Co.

- Hitchcock, Henry-Russell (1977). Architecture:Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries. The Pelican History of Art. Harmonsworth: Penguin Books.

- Pevsner, Nikolaus (1963). Herefordshire. The Buildings of England. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-071025-6.

- Pevsner, Nikolaus (1968). Worcestershire. The Buildings of England. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books.

- Sherwood, Jennifer; Pevsner, Nikolaus (1974). Oxfordshire. The Buildings of England. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-071045-0.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to George Gilbert Scott. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Scott, Sir George Gilbert. |

-

"Scott, George Gilbert". Dictionary of National Biography. London: Smith, Elder & Co. 1885–1900.

"Scott, George Gilbert". Dictionary of National Biography. London: Smith, Elder & Co. 1885–1900. - "Sir George Gilbert Scott". Metalwork. Victoria and Albert Museum. Retrieved 18 August 2007.

- "George Gilbert Scott's workhouse designs". The Workhouse. The Workhouse. Retrieved 9 September 2008.

- St Johns Church Bromsgrove

- Sir George Gilbert Scott, the unsung hero of British architecture

- Profile on Royal Academy of Arts Collections