Sino-Tibetan languages

| Sino-Tibetan | |||

|---|---|---|---|

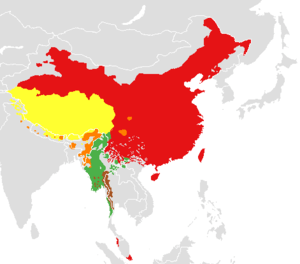

| Geographic distribution | East Asia, Southeast Asia, South Asia | ||

| Linguistic classification | One of the world's primary language families | ||

| Subdivisions | Some 40 well-established low-level groups, but no agreement on higher-level groupings | ||

| ISO 639-2 / 5 | sit | ||

| Linguasphere | 79- (phylozone) | ||

| Glottolog | sino1245 | ||

|

Major branches of Sino-Tibetan:

| |||

The Sino-Tibetan languages, in a few sources also known as Tibeto-Burman or Trans-Himalayan, are a family of more than 400 languages spoken in East Asia, Southeast Asia and South Asia. The family is second only to Indo-European in terms of the number of native speakers. The Sino-Tibetan languages with the most native speakers are the varieties of Chinese (1.3 billion speakers, the most of any language on Earth if counted as a single language), Burmese (33 million), and the Tibetic languages (8 million); but many Sino-Tibetan languages are spoken by small communities in remote mountain areas and as such are poorly documented.

Several low-level groupings are well established, but the higher-level structure of the family remains unclear. Although the family is often presented as divided into Sinitic and Tibeto-Burman branches, a common origin of the non-Sinitic languages has never been demonstrated and is rejected by an increasing number of researchers .

History

A genetic relationship between Chinese, Tibetan, Burmese and other languages was first proposed in the early 19th century and is now broadly accepted. The initial focus on languages of civilizations with long literary traditions has been broadened to include less widely spoken languages, some of which have only recently, or never, been written. However, the reconstruction of the family is much less developed than for families such as Indo-European or Austroasiatic. Difficulties have included the great diversity of the languages, the lack of inflexion in many of them, and the effects of language contact. In addition, many of the smaller languages are spoken in mountainous areas that are difficult to access, and are often also sensitive border zones.[1]

Early work

During the 18th century, several scholars had noticed parallels between Tibetan and Burmese, both languages with extensive literary traditions. Early in the following century, Brian Houghton Hodgson and others noted that many non-literary languages of the highlands of northeast India and Southeast Asia were also related to these. The name "Tibeto-Burman" was first applied to this group in 1856 by James Richardson Logan, who added Karen in 1858.[2][3] The third volume of the Linguistic Survey of India, edited by Sten Konow, was devoted to the Tibeto-Burman languages of British India.[4]

Studies of the "Indo-Chinese" languages of Southeast Asia from the mid-19th century by Logan and others revealed that they comprised four families: Tibeto-Burman, Tai, Mon–Khmer and Malayo-Polynesian. Julius Klaproth had noted in 1823 that Burmese, Tibetan and Chinese all shared common basic vocabulary but that Thai, Mon, and Vietnamese were quite different.[5][6] Ernst Kuhn envisaged a group with two branches, Chinese-Siamese and Tibeto-Burman.[lower-alpha 1] August Conrady called this group Indo-Chinese in his influential 1896 classification, though he had doubts about Karen. Conrady's terminology was widely used, but there was uncertainty regarding his exclusion of Vietnamese. Franz Nikolaus Finck in 1909 placed Karen as a third branch of Chinese-Siamese.[7]

Jean Przyluski introduced the term sino-tibétain as the title of his chapter on the group in Meillet and Cohen's Les langues du monde in 1924.[8] He retained Conrady's two branches of Tibeto-Burman and "Sino-Daic", with Miao–Yao included within Daic (Tai–Kadai). The English translation "Sino-Tibetan" first appeared in a short note by Przyluski and Luce in 1931.[9]

Shafer and Benedict

In 1935, the anthropologist Alfred Kroeber started the Sino-Tibetan Philology Project, funded by the Works Project Administration and based at the University of California, Berkeley. The project was supervised by Robert Shafer until late 1938, and then by Paul K. Benedict. Under their direction, the staff of 30 non-linguists collated all the available documentation of Sino-Tibetan languages. The result was eight copies of a 15-volume typescript entitled Sino-Tibetan Linguistics.[4][lower-alpha 2] This work was never published, but furnished the data for a series of papers by Shafer, as well as Shafer's five-volume Introduction to Sino-Tibetan and Benedict's Sino-Tibetan, a Conspectus.[11]

Benedict completed the manuscript of his work in 1941, but it was not published until 1972.[12] Instead of building the entire family tree, he set out to reconstruct a Proto-Tibeto-Burman language by comparing five major languages, with occasional comparisons with other languages.[13] He reconstructed a two-way distinction on initial consonants based on voicing, with aspiration conditioned by pre-initial consonants that had been retained in Tibetic but lost in many other languages.[14] Thus, Benedict reconstructed the following initials:[15]

| TB | Tibetan | Jingpho | Burmese | Garo | Mizo | S'gaw Karen | Old Chinese[lower-alpha 3] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| *k | k(h) | k(h) ~ g | k(h) | k(h) ~ g | k(h) | k(h) ~ h | *k(h) |

| *g | g | g ~ k(h) | k | g ~ k(h) | k | k(h) ~ h | *gh |

| *ŋ | ŋ | ŋ | ŋ | ŋ | ŋ | y | *ŋ |

| *t | t(h) | t(h) ~ d | t(h) | t(h) ~ d | t(h) | t(h) | *t(h) |

| *d | d | d ~ t(h) | t | d ~ t(h) | t | d | *dh |

| *n | n | n | n | n | n | n | *n ~ *ń |

| *p | p(h) | p(h) ~ b | p(h) | p(h) ~ b | p(h) | p(h) | *p(h) |

| *b | b | b ~ p(h) | p | b ~ p(h) | p | b | *bh |

| *m | m | m | m | m | m | m | *m |

| *ts | ts(h) | ts ~ dz | ts(h) | s ~ tś(h) | s | s(h) | *ts(h) |

| *dz | dz | dz ~ ts ~ ś | ts | tś(h) | f | s(h) | ? |

| *s | s | s | s | th | th | θ | *s |

| *z | z | z ~ ś | s | s | f | θ | ? |

| *r | r | r | r | r | r | γ | *l |

| *l | l | l | l | l | l | l | *l |

| *h | h | ∅ | h | ∅ | h | h | *x |

| *w | ∅ | w | w | w | w | w | *gjw |

| *y | y | y | y | tś ~ dź | z | y | *dj ~ *zj |

Although the initial consonants of cognates tend to have the same place and manner of articulation, voicing and aspiration is often unpredictable.[16] This irregularity was attacked by Roy Andrew Miller,[17] though Benedict's supporters attribute it to the effects of prefixes that have been lost and are often unrecoverable.[18] The issue remains unsolved today.[16] It was cited together with the lack of reconstructable shared morphology, and evidence that much shared lexical material has been borrowed from Chinese into Tibeto-Burman, by Christopher Beckwith, one of the few scholars still arguing that Chinese is not related to Tibeto-Burman.[19][20]

Study of literary languages

Old Chinese is by far the oldest recorded Sino-Tibetan language, with inscriptions dating from 1200 BC and a huge body of literature from the first millennium BC, but the Chinese script is not alphabetic. Scholars have sought to reconstruct the phonology of Old Chinese by comparing the obscure descriptions of the sounds of Middle Chinese in medieval dictionaries with phonetic elements in Chinese characters and the rhyming patterns of early poetry. The first complete reconstruction, the Grammata Serica Recensa of Bernard Karlgren, was used by Benedict and Shafer. It was somewhat unwieldy, with many sounds with a highly non-uniform distribution.[21] Later scholars have refined Karlgren's work by drawing on a range of other sources. Some proposals were based on cognates in other Sino-Tibetan languages, though workers have also found solely Chinese evidence for them.[22] For example, recent reconstructions of Old Chinese have reduced Karlgren's 15 vowels to a six-vowel system originally suggested by Nicholas Bodman on the basis of comparisons with Tibetic.[23] Similarly, Karlgren's *l has been recast as *r, with a different initial interpreted as *l, matching Tibeto-Burman cognates, but also supported by Chinese transcriptions of foreign names.[24] A growing number of scholars believe that Old Chinese did not use tones, and that the tones of Middle Chinese developed from final consonants. One of these, *-s, is believed to be a suffix, with cognates in other Sino-Tibetan languages.[25]

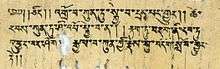

Tibetic has extensive written records from the adoption of writing by the Tibetan Empire in the mid-7th century. The earliest records of Burmese (such as the 12th-century Myazedi inscription) are more limited, but later an extensive literature developed. Both languages are recorded in alphabetic scripts ultimately derived from the Brahmi script of Ancient India. Most comparative work has used the conservative written forms of these languages, following the dictionaries of Jäschke (Tibetan) and Judson (Burmese), though both contain entries from a wide range of periods.[26]

There are also extensive records in Tangut, the language of the Western Xia (1038–1227). Tangut is recorded in a Chinese-inspired logographic script, whose interpretation presents many difficulties, even though multilingual dictionaries have been found.[27]

Gong Hwang-cherng has compared Old Chinese, Tibetic, Burmese and Tangut in an effort to establish sound correspondences between those languages.[13][28] He found that Tibetic and Burmese /a/ correspond to two vowels, *a and *ə, in Old Chinese.[29] While this has been considered evidence for a separate Tibeto-Burman subgroup, Hill (2014) finds that Burmese still distinguishes the specific rhymes *-aj (> -ay) and *-əj (> -i), and hence the development *ə > *a should be considered to have occurred independently in Tibetan and Burmese. [30]

Fieldwork

The descriptions of non-literary languages used by Shafer and Benedict were often produced by missionaries and colonial administrators of varying linguistic skill.[31][32] Most of the smaller Sino-Tibetan languages are spoken in inaccessible mountainous areas, many of which are politically or militarily sensitive and thus closed to investigators. Until the 1980s, the best-studied areas were Nepal and northern Thailand.[33] In the 1980s and 1990s, new surveys were published from the Himalayas and southwestern China. Of particular interest was the discovery of a new branch of the family, the Qiangic languages of western Sichuan and adjacent areas.[34][35]

Classification

Several low-level branches of the family, particularly Lolo-Burmese, have been securely reconstructed, but in the absence of a secure reconstruction of a Sino-Tibetan proto-language, the higher-level structure of the family remains unclear.[36][37] Thus, a conservative classification of Sino-Tibetan/Tibeto-Burman would posit several dozen small coordinate families and isolates; attempts at subgrouping are either geographic conveniences or hypotheses for further research.

Li (1937)

In a survey in the 1937 Chinese Yearbook, Li Fang-Kuei described the family as consisting of four branches:[38][39]

- Indo-Chinese (Sino-Tibetan)

- Chinese

- Tai (later expanded to Kam–Tai)

- Miao–Yao (Hmong–Mien)

- Tibeto-Burman

Tai and Miao–Yao were included because they shared isolating typology, tone systems and some vocabulary with Chinese. At the time, tone was considered so fundamental to language that tonal typology could be used as the basis for classification. In the Western scholarly community, these languages are no longer included in Sino-Tibetan, with the similarities attributed to diffusion across the Mainland Southeast Asia linguistic area, especially since Benedict (1942).[39] The exclusions of Vietnamese by Kuhn and of Tai and Miao–Yao by Benedict were vindicated in 1954 when André-Georges Haudricourt demonstrated that the tones of Vietnamese were reflexes of final consonants from Proto-Mon–Khmer.[40]

Many Chinese linguists continue to follow Li's classification.[lower-alpha 4][39] However, this arrangement remains problematic. For example, there is disagreement over whether to include the entire Tai–Kadai family or just Kam–Tai (Zhuang–Dong excludes the Kra languages), because the Chinese cognates that form the basis of the putative relationship are not found in all branches of the family and have not been reconstructed for the family as a whole. In addition, Kam–Tai itself no longer appears to be a valid node within Tai–Kadai.

Benedict (1942)

Benedict overtly excluded Vietnamese (placing it in Mon–Khmer) as well as Hmong–Mien and Tai–Kadai (placing them in Austro-Tai). He otherwise retained the outlines of Conrady's Indo-Chinese classification, though putting Karen in an intermediate position:[41][42]

- Sino-Tibetan

- Chinese

- Tibeto-Karen

- Karen

- Tibeto-Burman

Shafer (1955)

Shafer criticized the division of the family into Tibeto-Burman and Sino-Daic branches, which he attributed to the different groups of languages studied by Konow and other scholars in British India on the one hand and by Henri Maspero and other French linguists on the other.[43] He proposed a detailed classification, with six top-level divisions:[44][45][lower-alpha 5]

- Sino-Tibetan

- Sinitic

- Daic

- Bodic

- Burmic

- Baric

- Karenic

Shafer was sceptical of the inclusion of Daic, but after meeting Maspero in Paris decided to retain it pending a definitive resolution of the question.[46][47]

Matisoff (1978)

James Matisoff abandoned Benedict's Tibeto-Karen hypothesis:

- Sino-Tibetan

- Chinese

- Tibeto-Burman

Some more-recent Western scholars, such as Bradley (1997) and La Polla (2003), have retained Matisoff's two primary branches, though differing in the details of Tibeto-Burman. However, Jacques (2006) notes, "comparative work has never been able to put forth evidence for common innovations to all the Tibeto-Burman languages (the Sino-Tibetan languages to the exclusion of Chinese)"[lower-alpha 6] and that "it no longer seems justified to treat Chinese as the first branching of the Sino-Tibetan family,"[lower-alpha 7] because the morphological divide between Chinese and Tibeto-Burman has been bridged by recent reconstructions of Old Chinese.

Starostin (1996)

Sergei Starostin proposed that both the Kiranti languages and Chinese are divergent from a "core" Tibeto-Burman of at least Bodish, Lolo-Burmese, Tamangic, Jinghpaw, Kukish, and Karen (other families were not analysed) in a hypothesis called Sino-Kiranti. The proposal takes two forms: that Sinitic and Kiranti are themselves a valid node or that the two are not demonstrably close, so that Sino-Tibetan has three primary branches:

- Sino-Tibetan (version 1)

- Sino-Kiranti

- Tibeto-Burman

- Sino-Tibetan (version 2)

- Chinese

- Kiranti

- Tibeto-Burman

Van Driem (1997, 2001)

Van Driem, like Shafer, rejects a primary split between Chinese and the rest, suggesting that Chinese owes its traditional privileged place in Sino-Tibetan to historical, typological, and cultural, rather than linguistic, criteria. He calls the entire family "Tibeto-Burman", a name he says has historical primacy,[48] but other linguists who reject a privileged position for Chinese continue to call the resulting family "Sino-Tibetan".

Like Matisoff, van Driem acknowledges that the relationships of the "Kuki–Naga" languages (Kuki, Mizo, Meitei, etc.), both amongst each other and to the other languages of the family, remain unclear. However, rather than placing them in a geographic grouping, as Matisoff does, van Driem leaves them unclassified. He has proposed several hypotheses, including the reclassification of Chinese to a Sino-Bodic subgroup:

- Tibeto-Burman

- Western (Baric, Brahmaputran, or Sal)

- Eastern

- Northern (Sino-Bodic)

- Northwestern (Bodic): Bodish, Kirantic, West Himalayish, Tamangic and several isolates

- Northeastern (Sinitic)

- Southern

- Southwestern: Lolo-Burmese, Karenic

- Southeastern: Qiangic, Jiarongic

- Northern (Sino-Bodic)

- a number of other small families and isolates as primary branches (Newar, Nungish, Magaric, etc.)

Van Driem points to two main pieces of evidence establishing a special relationship between Sinitic and Bodic and thus placing Chinese within the Tibeto-Burman family. First, there are a number of parallels between the morphology of Old Chinese and the modern Bodic languages. Second, there is an impressive body of lexical cognates between the Chinese and Bodic languages, represented by the Kirantic language Limbu.[49]

In response, Matisoff notes that the existence of shared lexical material only serves to establish an absolute relationship between two language families, not their relative relationship to one another. Although some cognate sets presented by van Driem are confined to Chinese and Bodic, many others are found in Sino-Tibetan languages generally and thus do not serve as evidence for a special relationship between Chinese and Bodic.[50]

Van Driem (2001)

Van Driem has also proposed a "fallen leaves" model that lists dozens of well-established low-level groups while remaining agnostic about intermediate groupings of these.[51] In the most recent version, 42 groups are identified:[52]

- Bodish

- Tshangla

- West Himalayish

- Tamangic

- Newar

- Kiranti

- Lepcha

- Magaric

- Chepangic

- Raji–Raute

- Dura

- 'Ole

- Gongduk

- Lhokpu

- Siangic

- Kho-Bwa

- Hruso

- Digaro

- Midzu

- Tani

- Dhimal

- Bodo–Koch + Konyak

- Ao

- Angami–Pochuri

- Tangkhul

- Zeme

- Meitei

- Karbi

- Sinitic

- Bai

- Tujia

- Lolo-Burmese

- Qiangic

- Ersuish

- Naic

- rGyalrongic

- Kachin–Luic

- Nungish

- Karenic

- Pyu

- Mru

- Kukish

Van Driem also suggested that the Sino-Tibetan language family be renamed "Trans-Himalayan", which he considers to be more neutral.[53]

Blench and Post (2013)

Roger Blench and Mark W. Post have criticized the applicability of conventional Sino-Tibetan classification schemes to minor languages lacking an extensive written history (unlike Chinese, Tibetic, and Burmese). They find that the evidence for the subclassification or even ST affiliation at all of several minor languages of northeastern India, in particular, is either poor or absent altogether.

While relatively little has been known about the languages of this region up to and including the present time, this has not stopped scholars from proposing that these languages either constitute or fall within some other Tibeto-Burman subgroup. However, in absence of any sort of systematic comparison – whether the data are thought reliable or not – such "subgroupings" are essentially vacuous. The use of pseudo-genetic labels such as "Himalayish" and "Kamarupan" inevitably give an impression of coherence which is at best misleading.— Blench & Post (2013), p. 3

In their view, many such languages would for now be best considered unclassified, or "internal isolates" within the family. They propose a provisional classification of the remaining languages:

- Sino-Tibetan

- Karbi (Mikir)

- Mruish

- (unnamed group)

- (unnamed group)

- (unnamed group)

- Western: Gongduk, 'Ole, Mahakiranti, Lepcha, Kham–Magaric–Chepang, Tamangic, and Lhokpu

- Karenic

- Jingpho–Konyak–Bodo

- Eastern

- Tujia

- Bai

- Northern Qiangic

- Southern Qiangic

- (unnamed group)

- Chinese (Sinitic)

- Lolo-Burmese–Naic

- Bodish

- Nungish

However, because they propose that the three best-known branches may actually be much closer related to each other than they are to "minor" Sino-Tibetan languages, Blench and Post argue that "Sino-Tibetan" or "Tibeto-Burman" are inappropriate names for a family whose earliest divergences led to different languages altogether. They support the proposed name "Trans-Himalayan".

Development of Dialects and Languages

Change in Word Structure

The concept of drift, proposed by American linguist Edward Sapir, occur in many languages and dialects in the Sino-Tibetan language group. Proto-Chinese language and Proto-Tibeto-Burman language are both agglutinative language. The change in Proto-Chinese language to Old Chinese around the Shang Dynasty could be found in the Book of songs when the classifications of the noun, verbs, and modifier were all depended on prefixes such as *s-, *p-, *-k.[54] After the Warring State Period in China, Old Chinese was developed and started to use tones as the classification of words.[55] The suffix *-s also presented in the new classification system. The characteristics of Old Chinese were maintained in most dialects of southern China.[56]

Chinese dialect of Min and Wu that mainly spoke in southern part of China had similarities of the pronunciation of reptiles and birds compare with Old Tai-Kadai language according to You Rujie's research. The prefix uses for differentiating reptiles and birds in the Chinese dialects shown similar feature with the Old Tai-Kadai language.[57] The old Tai-Kadai language was mainly employed in Xiangxi and Guizhou area of China, You believed that this unique prefixes maintained by both the local dialects and the old Tai-Kadai language could be a product of the local environmental influence.[58]

Dialects in the Tibeto-Burman language developed more conservatively; they keep the rules for pronunciation and word structure the same compared to the Proto-Tibeto-Burman language. The Tibetic languages are classified between fusional language and analytic language; the Lolo-Burmese languages are mostly analytic language, and the Jingpho languages are a mix of agglutinative language and fusional language.[59]The Bodo–Koch languages and the Kuki-Chin–Naga languages kept some particular characteristic of the Proto-Tibeto-Burman language such as agglutination and vowel prefixes. This phenomenon could be that the two language group were separated early from the Proto-Tibeto-Burman language therefore did not undergoes much development. Same thing happens to the Sino-Tibetan language, where its agglutination property was kept even when it developed into an analytic language. Old Tibetan and the Qiangic language both have the structure of consonant cluster caused by the dropping of vowel prefixes, which is believed to be the same structure Proto-Sino-Tibetan language owned.[60]

Old Burmese and Old Tibetan dropped the vowel prefixes during the dialect acquisition, leaving only the Tibeto-Burmese language, the Jingpho language, the Bodo–Koch languages and the Kuki-Chin–Naga languages that kept the vowel form of prefixes. The Lolo-Burmese languages and other languages from the Bodish-Himalayish language group preferred suffixes structure which they inherited from the Tibetan-Qiangic-Lolo-Burmese languages group. Their similarities could be proven by example like the phonetics of the Tibetic language for “sun”: ŋi ma; the Achang language for 'sun': ni31 mɔ31; the Hakun language for “sun”: nɔ55 ma33; and the Naxi language for “sun”: ŋi33 me33. These inherited suffixes were later chosen to keep in the languages and became widespread in dialects of Old Tibetan, which caused the usage of the prefix in the modern language to decrease.[61]

According to Dai Qingxia, half of the vocabulary in the Jingpho language are disyllabic as well as most of the noun of Jingpho. This significant amount of disyllabic words came from the consonant cluster in monosyllabic words and compound words mainly found in the Proto-Tibeto-Burman language.[62] The development of the Sino-Tibetan language had been focused on solving the problem of phoneme rhyme, as well as coordinate the crucial point between monosyllabic morpheme and disyllabic word. Because the Sino-Tibetan language consists of a monosyllabic root, prefix and suffix are in need for classifying word sense and point of view. The prefix *a- appeared in many Sino-Tibetan dialects to coordinate different morpheme structures. The repetition of a syllable has the same coordination effect.[63]

Change in Tone

Chinese language, Hmong-Mien languages, and Tai–Kadai languages are analytic languages that have similar grammar, pronunciation, and syllable structure.They all started with four tones, soon afterward developed into different phonological tones such as checked tone because of the voiced and voiceless properties of the initial. The aspiration of the initial and the length of the vowel in checked tone led to further tone development of dialects in these languages. Cantonese in Jiangyang area for the Chinese language developed eight different tones because of the length of the vowel. The aspiration property also determined the tone development of Tai-Kadai language, of which the tone eventually developed into sixteen types of tone.[64] Zongdi dialect of Hmong-Mien language had also experienced the change in tone because of the aspiration property.[65]

Typology

Word order

Except for the Chinese, Karen, and Bai languages, the usual word order in Sino-Tibetan languages is object–verb. Most scholars believe this to be the original order, with Chinese, Karen and Bai having acquired subject–verb–object order due to the influence of neighbouring languages in the Mainland Southeast Asia linguistic area.[66] However, Chinese and Bai differ from almost all other VO languages in the world in placing relative clauses before the nouns they modify.[67]

Morphology

Hodgson had in 1849 noted a dichotomy between "pronominalized" (inflecting) languages, stretching across the Himalayas from Himachal Pradesh to eastern Nepal, and "non-pronominalized" (isolating) languages. Konow (1909) explained the pronominalized languages as due to a Munda substratum, with the idea that Indo-Chinese languages were essentially isolating as well as tonal. Maspero later attributed the putative substratum to Indo-Aryan. It was not until Benedict that the inflectional systems of these languages were recognized as (partially) native to the family. Scholars disagree over the extent to which the agreement system in the various languages can be reconstructed for the proto-language.[68][69]

In morphosyntactic alignment, many Tibeto-Burman languages have ergative and/or anti-ergative (an argument that is not an actor) case marking. However, the anti-ergative case markings can not be reconstructed at higher levels in the family and are thought to be innovations.[70]

Classifiers and Definite Marking

There is no language originally in the Proto-Sino-Tibetan language group that had classifiers, but some sub-language group did develop some properties of classifier,[71][72] such as the Lolo-Burmese language which had cognate nouns as classifiers.[73] Tibetan-Burman languages and Sinitic languages also developed classifiers that are used more commonly in South East Asia and are mainly use without numerals. Such as in the Rawang language lègā tiq bok [book one classifier] meaning ‘one book', lègā bok meaning ‘the book’; in Cantonese yat55 ga33 che55 [one classifier vehicle] meaning ‘one car’, ga33 che55 meaning ‘the car’ (verbally).[74] Some other classifiers in Tibetan-Burman languages and Sinitic languages developed the same use as definite or specific marking. Definite marking did not appear in the Proto-Sino-Tibetan language either, but there is some use of it in the Qiangic language of the Tibetan-Burmese languages,[75] where the markings seem to evolve from demonstratives.[76]

Vocabulary

| gloss | Old Chinese[77] | Old Tibetan[78] | Old Burmese[78] | Jingpho[79] | Garo[79] | Limbu[80] | Kanauri[81] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| "one" | 一 *ʔjit | – | ac | – | – | – | id |

| 隻 *tjek "single" | gcig | tac | – | – | thik | – | |

| "two" | 二 *njijs | gnyis | nhac | – | gin-i | nɛtchi | niš |

| "three" | 三 *sum | gsum | sumḥ | mə̀sūm | git-tam | sumsi | sum |

| "four" | 四 *sjijs | bzhi | liy | mə̀lī | bri | lisi | pə: |

| "five" | 五 *ŋaʔ | lnga | ṅāḥ | mə̀ŋā | boŋ-a | nasi | ṅa |

| "six" | 六 *C-rjuk | drug | khrok | krúʔ | dok | tuksi | țuk |

| "seven" | 七 *tsʰjit | – | khu-nac | sə̀nìt | sin-i | nusi | štiš |

| "eight" | 八 *pret | brgyad | rhac | mə̀tshát | cet | yɛtchi | rəy |

| "nine" | 九 *kjuʔ | dgu | kuiḥ | cə̀khù | sku | – | sgui |

| "ten" | 十 *gjəp | – | kip[82] | – | – | gip | – |

| – | bcu | chay | shī | ci-kuŋ | – | səy |

External classification

Beyond the traditionally recognized families of Southeast Asia, a number of possible broader relationships have been suggested. One of these is the "Sino-Caucasian" hypothesis of Sergei Starostin, which posits that the Yeniseian languages and North Caucasian languages form a clade with Sino-Tibetan. The Sino-Caucasian hypothesis has been expanded by others to "Dené–Caucasian" to include the Na-Dené languages of North America, Burushaski, Basque and, occasionally, Etruscan. Edward Sapir had commented on a connection between Na-Dené and Sino-Tibetan.[83] A narrower binary Dené–Yeniseian family has recently been well-received, though not conclusively demonstrated. In contrast, Laurent Sagart proposes a Sino-Austronesian family relating Sino-Tibetan to the Austronesian and Tai–Kadai languages.[84]

Peoples and languages

Proportion of first-language speakers of larger branches of Sino-Tibetan[85]

There is no ethnic unity among the many peoples who speak Sino-Tibetan languages. The most numerous are the Han Chinese, numbering 1.4+ billion(in China alone). The Hui (10 million) also speak Chinese but are officially classified as ethnically distinct by the Chinese government. The more numerous peoples speaking other Sino-Tibetan languages are the Burmese (42 million), Yi (Lolo) (7 million), Tibetans (6 million), Karen (5 million), Tripuri (1.3 million), Meiteis (1.5 million), Gurung (1 million), Naga (1.2 million), Limbu (4.3 million), Tamang (1.1 million), Chin (1.1 million), Newar (1 million), Bodo (2.2 million), and Kachin (1 million). The Burmese live in Burma (Myanmar). Kachin, Karen, Red Karen, and Chin peoples live in the Rakhine, Kachin, Kayin, Kayah, and Chin states of Burma. Tibetans live in the Tibet Autonomous Region, Qinghai, western Sichuan, Gansu, and northern Yunnan provinces in China and in Ladakh in the Kashmir region ofIndwheren ofIndwhereas Maniereas Manipuris, Mizo, Naga, Tripuri and Garo live in Manipur, Mizoram, Nagaland, Tripura, and Meghalaya states of India. Bodo and Karbi live in Assam, India, whereas Tagin, Adi, Nishi, Apa Tani, Galo, and Idu Mishmis live in Arunachal Pradesh, India. The Newar and Tamang live in Nepal and Sikkim, India.

J. A. Matisoff proposed that the Urheimat of the Sino-Tibetan languages was around the upper reaches of the Yangtze, Brahmaputra, Salween, and Mekong. This view is in accordance with the hypothesis that bubonic plague, cholera, and other diseases made the easternmost foothills of the Himalayas between China and India difficult for people outside to migrate in but relatively easily for the indigenous people, who had been adapted to the environment, to migrate out.[86]

Notes

- ↑ Kuhn (1889), p. 189: "wir das Tibetisch-Barmanische einerseits, das Chinesisch-Siamesische anderseits als deutlich geschiedene und doch wieder verwandte Gruppen einer einheitlichen Sprachfamilie anzuerkennen haben." (also quoted in van Driem (2001), p. 264.)

- ↑ The volumes were: 1. Introduction and bibliography, 2. Bhotish, 3. West Himalayish, 4. West central Himalayish, 5. East Himalayish, 6–7. Digarish–Nungish, 8. Dzorgaish, 9. Hruso, 10. Dhimalish, 11. Baric, 12. Burmish–Lolish, 13. Kachinish, 14. Kukish, 15. Mruish.[10]

- ↑ Karlgren's reconstruction, with aspiration as 'h' and 'i̯' as 'j' to aid comparison.

- ↑ See, for example, the "Sino-Tibetan" (汉藏语系 Hàn-Zàng yǔxì) entry in the "languages" (語言文字, Yǔyán-Wénzì) volume of the Encyclopedia of China (1988).

- ↑ For Shafer, the suffix "-ic" denoted a primary division of the family, whereas the suffix "-ish" denoted a sub-division of one of those.

- ↑ les travaux de comparatisme n’ont jamais pu mettre en évidence l’existence d’innovations communes à toutes les langues « tibéto-birmanes » (les langues sino-tibétaines à l’exclusion du chinois)

- ↑ il ne semble plus justifié de traiter le chinois comme le premier embranchement primaire de la famille sino-tibétaine

References

- ↑ Handel (2008), pp. 422, 434–436.

- ↑ Logan (1856), p. 31.

- ↑ Logan (1858).

- 1 2 Hale (1982), p. 4.

- ↑ van Driem (2001), p. 334.

- ↑ Klaproth (1823), pp. 346, 363–365.

- ↑ van Driem (2001), p. 344.

- ↑ Sapir (1925), p. 373.

- ↑ Przyluski & Luce (1931).

- ↑ Miller (1974), p. 195.

- ↑ Miller (1974), pp. 195–196.

- ↑ Matisoff (1991), p. 473.

- 1 2 Handel (2008), p. 434.

- ↑ Benedict (1972), pp. 20–21.

- ↑ Benedict (1972), pp. 17–18, 133–139, 164–171.

- 1 2 Handel (2008), pp. 425–426.

- ↑ Miller (1974), p. 197.

- ↑ Matisoff (2003), p. 16.

- ↑ Beckwith (1996).

- ↑ Beckwith (2002b).

- ↑ Matisoff (1991), pp. 471–472.

- ↑ Baxter (1992), pp. 25–26.

- ↑ Bodman (1980), p. 47.

- ↑ Baxter (1992), pp. 197, 199–202.

- ↑ Baxter (1992), pp. 315–317.

- ↑ Beckwith (2002a), pp. xiii–xiv.

- ↑ Thurgood (2003), p. 17.

- ↑ Gong (1980).

- ↑ Handel (2008), p. 431.

- ↑ Hill (2014), pp. 97–104.

- ↑ Matisoff (1991), pp. 472–473.

- ↑ Hale (1982), pp. 4–5.

- ↑ Matisoff (1991), pp. 470, 476–478.

- ↑ Handel (2008), p. 435.

- ↑ Matisoff (1991), p. 482.

- ↑ Handel (2008), p. 426.

- ↑ DeLancey (2009), p. 695.

- ↑ Li (1937), pp. 60–63.

- 1 2 3 Handel (2008), p. 424.

- ↑ Matisoff (1991), p. 487.

- ↑ Benedict (1942), p. 600.

- ↑ Benedict (1972), pp. 2–4.

- ↑ Shafer (1955), pp. 94–96.

- ↑ Shafer (1955), pp. 99–108.

- ↑ Shafer (1966), p. 1.

- ↑ Shafer (1955), pp. 97–99.

- ↑ van Driem (2001), pp. 343–344.

- ↑ van Driem (2001), p. 383.

- ↑ van Driem (1997).

- ↑ Matisoff (2000).

- ↑ van Driem (2001), p. 403.

- ↑ van Driem (2014), p. 19.

- ↑ van Driem (2007), p. 226.

- ↑ Wu (1987).

- ↑ Wang (1980), p. 221.

- ↑ Wu (2002), pp. 9-10.

- ↑ You (1982).

- ↑ Wu (2002), p. 12.

- ↑ Sun (1996).

- ↑ Wu (2002), pp. 10,12.

- ↑ Wu (2002), p. 10.

- ↑ Dai (1997).

- ↑ Wu (2002), p. 11.

- ↑ Shi (1991).

- ↑ Wu (2002).

- ↑ Dryer (2003), pp. 43–45.

- ↑ Dryer (2003), pp. 50.

- ↑ Handel (2008), p. 430.

- ↑ LaPolla (2003), pp. 29–32.

- ↑ LaPolla (2003), pp. 34–35.

- ↑ Xu (1989), pp. 15-23.

- ↑ Dai (1994), pp. 166-181.

- ↑ Bradley (2012), pp. 171-192.

- ↑ Baron (1973).

- ↑ LaPolla & Huang (2003).

- ↑ Thurgood & LaPolla (2017), p. 46.

- ↑ Baxter (1992).

- 1 2 Hill (2012).

- 1 2 Burling (1983), p. 28.

- ↑ van Driem (1987), pp. 32–33.

- ↑ Sharma (1988), p. 116.

- ↑ Yanson (2006), p. 106.

- ↑ Shafer (1952).

- ↑ Sagart (2005).

- ↑ Lewis, Simons & Fennig (2015).

- ↑ "LANGUAGE CHANGE, CONJUGATIONAL MORPHOLOGY AND THE SINO-TIBETAN URHEIMAT" by G. van Driem

Works cited

- Baxter, William H. (1992), A Handbook of Old Chinese Phonology, Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, ISBN 978-3-11-012324-1.

- Beckwith, Christopher I. (1996), "The Morphological Argument for the Existence of Sino-Tibetan", Pan-Asiatic Linguistics: Proceedings of the Fourth International Symposium on Languages and Linguistics, January 8–10, 1996, Bangkok: Mahidol University at Salaya, pp. 812–826.

- —— (2002a), "Introduction", in Beckwith, Christopher, Medieval Tibeto-Burman languages, Brill, pp. xiii–xix, ISBN 978-90-04-12424-0.

- —— (2002b), "The Sino-Tibetan problem", in Beckwith, Christopher, Medieval Tibeto-Burman languages, Brill, pp. 113–158, ISBN 978-90-04-12424-0.

- Benedict, Paul K. (1942), "Thai, Kadai, and Indonesian: A New Alignment in Southeastern Asia", American Anthropologist, 44 (4): 576–601, JSTOR 663309, doi:10.1525/aa.1942.44.4.02a00040.

- —— (1972), Sino-Tibetan: A Conspectus (PDF), Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-08175-7.

- Blench, Roger; Post, Mark (2013), "Rethinking Sino-Tibetan phylogeny from the perspective of North East Indian languages", in Hill, Nathan W.; Owen-Smith, Thomas, Trans-Himalayan Linguistics, Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, pp. 71–104, ISBN 978-3-11-031083-2.

- Bodman, Nicholas C. (1980), "Proto-Chinese and Sino-Tibetan: data towards establishing the nature of the relationship", in van Coetsem, Frans; Waugh, Linda R., Contributions to historical linguistics: issues and materials, Leiden: E. J. Brill, pp. 34–199, ISBN 978-90-04-06130-9.

- Burling, Robbins (1983), "The Sal Languages" (PDF), Linguistics of the Tibeto-Burman Area, 7 (2): 1–32.

- DeLancey, Scott (2009), "Sino-Tibetan languages", in Comrie, Bernard, The World's Major Languages (2nd ed.), Routledge, pp. 693–702, ISBN 978-1-134-26156-7.

- van Driem, George (1987), A grammar of Limbu, Mouton grammar library, 4, Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, ISBN 978-3-11-011282-5.

- —— (1997), "Sino-Bodic", Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, 60 (3): 455–488, doi:10.1017/S0041977X0003250X.

- —— (2001), Languages of the Himalayas: An Ethnolinguistic Handbook of the Greater Himalayan Region, Brill, ISBN 978-90-04-12062-4.

- —— (2007), "The diversity of the Tibeto-Burman language family and the linguistic ancestry of Chinese" (PDF), Bulletin of Chinese Linguistics, 1 (2): 211–270.

- —— (2014), "Trans-Himalayan" (PDF), in Owen-Smith, Thomas; Hill, Nathan W., Trans-Himalayan Linguistics: Historical and Descriptive Linguistics of the Himalayan Area, Berlin: de Gruyter, pp. 11–40, ISBN 978-3-11-031083-2.

- Dryer, Matthew S. (2003), "Word order in Sino-Tibetan languages from a typological and geographical perspective", in Thurgood, Graham; LaPolla, Randy J., The Sino-Tibetan languages, London: Routledge, pp. 43–55, ISBN 978-0-7007-1129-1.

- Gong, Hwang-cherng (1980), "A Comparative Study of the Chinese, Tibetan, and Burmese Vowel Systems", Bulletin of the Institute of History and Philology, Academia Sinica, 51: 455–489.

- Hale, Austin (1982), Research on Tibeto-Burman Languages, State-of-the-art report, Trends in linguistics, 14, Walter de Gruyter, ISBN 978-90-279-3379-9.

- Handel, Zev (2008), "What is Sino-Tibetan? Snapshot of a Field and a Language Family in Flux", Language and Linguistics Compass, 2 (3): 422–441, doi:10.1111/j.1749-818X.2008.00061.x.

- Hill, Nathan W. (2012), "The six vowel hypothesis of Old Chinese in comparative context", Bulletin of Chinese Linguistics, 6 (2): 1–69, doi:10.1163/2405478x-90000100.

- —— (2014), "Cognates of Old Chinese *-n, *-r, and *-j in Tibetan and Burmese", Cahiers de Linguistique Asie Orientale, 43 (2): 91–109, doi:10.1163/19606028-00432p02

- Klaproth, Julius (1823), Asia Polyglotta, Paris: B.A. Shubart.

- Kuhn, Ernst (1889), "Beiträge zur Sprachenkunde Hinterindiens" (PDF), Sitzungsberichte der Königlichen Bayerischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, Philosophisch-Philologische und Historische Klasse, Sitzung vom 2 März 1889, pp. 189–236.

- LaPolla, Randy J. (2003), "Overview of Sino-Tibetan morphosyntax", in Thurgood, Graham; LaPolla, Randy J., The Sino-Tibetan languages, London: Routledge, pp. 22–42, ISBN 978-0-7007-1129-1.

- Lewis, M. Paul; Simons, Gary F.; Fennig, Charles D., eds. (2015), Ethnologue: Languages of the World (Eighteenth ed.), Dallas, Texas: SIL International.

- Li, Fang-Kuei (1937), "Languages and Dialects", in Shih, Ch'ao-ying; Chang, Ch'i-hsien, The Chinese Year Book, Commercial Press, pp. 59–65, reprinted as Li, Fang-Kuei (1973), "Languages and Dialects of China", Journal of Chinese Linguistics, 1 (1): 1–13, JSTOR 23749774.

- Logan, James R. (1856), "The Maruwi of the Baniak Islands", Journal of the Indian Archipelago and Eastern Asia, 1 (1): 1–42.

- —— (1858), "The West-Himalaic or Tibetan tribes of Asam, Burma and Pegu", Journal of the Indian Archipelago and Eastern Asia, 2 (1): 68–114.

- Matisoff, James A. (1991), "Sino-Tibetan Linguistics: Present State and Future Prospects", Annual Review of Anthropology, 20: 469–504, JSTOR 2155809, doi:10.1146/annurev.anthro.20.1.469.

- —— (2000), "On 'Sino-Bodic' and Other Symptoms of Neosubgroupitis", Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, 63 (3): 356–369, JSTOR 1559492, doi:10.1017/s0041977x00008442.

- —— (2003), Handbook of Proto-Tibeto-Burman: System and Philosophy of Sino-Tibetan Reconstruction, Berkeley: University of California Press, ISBN 978-0-520-09843-5.

- Miller, Roy Andrew (1974), "Sino-Tibetan: Inspection of a Conspectus", Journal of the American Oriental Society, 94 (2): 195–209, JSTOR 600891, doi:10.2307/600891.

- Przyluski, J.; Luce, G. H. (1931), "The Number 'A Hundred' in Sino-Tibetan", Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, 6 (3): 667–668, doi:10.1017/S0041977X00093150.

- Sagart, Laurent (2005), "Sino-Tibetan–Austronesian: an updated and improved argument", in Sagart, Laurent; Blench, Roger; Sanchez-Mazas, Alicia, The Peopling of East Asia: Putting Together Archaeology, Linguistics and Genetics, London: Routledge Curzon, pp. 161–176, ISBN 978-0-415-32242-3.

- Sapir, Edward (1925), "Review: Les Langues du Monde", Modern Language Notes, 40 (6): 373–375, JSTOR 2914102.

- Shafer, Robert (1952), "Athapaskan and Sino-Tibetan", International Journal of American Linguistics, 18 (1): 12–19, JSTOR 1263121, doi:10.1086/464142.

- —— (1955), "Classification of the Sino-Tibetan languages", Word (Journal of the Linguistic Circle of New York), 11 (1): 94–111, doi:10.1080/00437956.1955.11659552.

- —— (1966), Introduction to Sino-Tibetan, 1, Wiesbaden: Otto Harrassowitz, ISBN 978-3-447-01559-2.

- Sharma, Devidatta (1988), A Descriptive Grammar of Kinnauri, Mittal Publications, ISBN 978-81-7099-049-9.

- Thurgood, Graham (2003), "A subgrouping of the Sino-Tibetan languages", in Thurgood, Graham; LaPolla, Randy J., The Sino-Tibetan languages, London: Routledge, pp. 3–21, ISBN 978-0-7007-1129-1.

- Yanson, Rudolf A. (2006), "Notes on the evolution of the Burmese phonological system", in Beckwith, Christopher I., Medieval Tibeto-Burman Languages II, Leiden: Brill, pp. 103–120, ISBN 978-90-04-15014-0.

- Wu, Anqi (1987), Han Zang yu shi dong he wan cheng ti qian zhui de can cui he tong yuan de dong ci ci gen

- Wang, Li (1980), Han Yu shi gao (zhong), Zhong hua shu ju, p. 221

- Wu, Anqi (2002), Han Zang yu tong yuan yan jiu, Beijing: Zhong yang min zu da xue chu ban she, pp. 9–12, ISBN 7810566113

- You, Rujie (1982), Lun Tai yu liang ci zai Han yu nan fang fang yan zhong de di ceng yi cui

- Sun, Hongkai (1996), Lun Zang Mian yu de yu fa xing shi

- Dai, Qingxia (1997), Jing Po yu ci de shuang yin jie hua dui yu fa de ying xiang

- Shi, Lin (1991), Tong yu sheng diao de gong shi biao xian he li shi yan bian

- Xu, Xijian (1987), On the origin and development of noun classifiers in JingPo (PDF), translated by LaPolla, Randy J., Minzu Yuwen, pp. 27–35

- Dai, Qingzia (1994), Zangmian yu geti liangci yanjiu [A study on numeral classifiers in Tibeto-Burman], Beijing: Zhongyang MInzu Xueyuan Chubanshe, pp. 166–181

- Bradley, David (2012), The characteristics of the Burmic family of Tibeto-Burman (PDF), pp. 171–192

- Baron, Stephen P. (1973), The classifier-alone-plus-noun construction: a study in areal diffusion, University of California, San Diego

- LaPolla, Randy J.; Huang, Chenglong (2003), A Grammar of Qiang, with Annotated Texts and Glossary, Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, ISBN 9783110197273

- Thurgood, Graham; LaPolla, Randy J. (2017), The Sino-Tibetan languages, New York: Routledge, p. 46, ISBN 978-1-138-78332-4

- General

- Bauman, James (1974), "Pronominal Verb Morphology in Tibeto-Burman" (PDF), Linguistics of the Tibeto-Burman Area, 1 (1): 108–155.

- Baxter, William H. (1995), "'A Stronger Affinity ... Than Could Have Been Produced by Accident': A Probabilistic Comparison of Old Chinese and Tibeto-Burman", in Wang, William S.-Y., The Ancestry of the Chinese Language, Journal of Chinese Linguistics Monographs, 8, Berkeley: Project on Linguistic Analysis, pp. 1–39, JSTOR 23826142.

- Benedict, Paul K. (1976), "Sino-Tibetan: Another Look", Journal of the American Oriental Society, 96 (2): 167–197, JSTOR 599822, doi:10.2307/599822.

- Blench, Roger; Post, Mark (2011), (De)classifying Arunachal languages: Reconstructing the evidence (PDF).

- Coblin, W. South (1986), A Sinologist's Handlist of Sino-Tibetan Lexical Comparisons, Monumenta Serica monograph series, 18, Nettetal: Steyler Verlag, ISBN 978-3-87787-208-6.

- van Driem, George (1995), "Black Mountain Conjugational Morphology, Proto-Tibeto-Burman Morphosyntax, and the Linguistic Position of Chinese" (PDF), Senri Ethnological Studies, 41: 229–259.

- —— (2003), "Tibeto-Burman vs. Sino-Tibetan", in Winter, Werner; Bauer, Brigitte L. M.; Pinault, Georges-Jean, Language in time and space: a Festschrift for Werner Winter on the occasion of his 80th birthday, Walter de Gruyter, pp. 101–119, ISBN 978-3-11-017648-3.

- Gong, Hwang-cherng (2002), Hàn Zàng yǔ yánjiū lùnwén jí 漢藏語硏究論文集 [Collected papers on Sino-Tibetan linguistics], Taipei: Academia Sinica, ISBN 957-671-872-4.

- Jacques, Guillaume (2006), "La morphologie du sino-tibétain", La linguistique comparative en France aujourd'hui.

- Kuhn, Ernst (1883), Über Herkunft und Sprache der transgangetischen Völker, Munich: Verlag d. k. b. Akademie.

- Starostin, Sergei; Peiros, Ilia (1996), A Comparative Vocabulary of Five Sino-Tibetan Languages, Melbourne University Press, OCLC 53387435.

External links

- James Matisoff, Tibeto-Burman languages and their subgrouping

- The Genetic Position of Chinese, by Guillaume Jacques

- Sino-Tibetan at the Linguist List MultiTree Project (not functional as of 2014): Genealogical trees attributed to Conrady 1896, Benedict 1942, Shafer 1955, Benedict 1972, Egerod 1991, Matisoff & Namkung 1996, Peiros 1998, Thurgood & LaPolla 2003, and Matisoff 2006. (Caution: The tree attributed to Bradley 2007 does not actually correspond to that article.)