Singer Motors

|

| |

| Private | |

| Industry |

Automobile industry Motorcycle until 1915 Bicycle industry until 1915 |

| Fate | Taken over |

| Successor | Rootes Group |

| Founded | 1875 |

| Founder | George Singer |

| Defunct | 1970 |

| Headquarters | Coventry, United Kingdom |

Area served |

United Kingdom Commonwealth of Nations |

| Products |

Automobiles Motorcycles until 1915 Bicycles until 1915 |

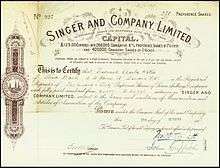

Singer Motors Limited was a British motor vehicle manufacturing business, originally a bicycle manufacturer founded as Singer & Co by George Singer, in 1874 in Coventry, England. Singer & Co's bicycle manufacture continued. From 1901 George Singer's Singer Motor Co made cars and commercial vehicles.

Singer Motor Co was the first motor manufacturer to make a small economy car that was a replica of a large car, showing a small car was a practical proposition.[1] It was much more sturdily built than otherwise similar cyclecars. With its four-cylinder ten horsepower engine the Singer Ten was launched at the 1912 Cycle and Motor Cycle Show at Olympia. William Rootes, Singer apprentice at the time of its development and consummate car-salesman, contracted to buy 50, the entire first year's supply.[1] It became a best-seller.[1] Ultimately Singer's business was acquired by his Rootes Group in 1956, which continued the brand until 1970, a few years following Rootes' acquisition by the American Chrysler corporation.

History

Bicycles

George Singer (1847–1909) began his bicycle-making business in Coventry in 1874.[2]

Engines, three-wheelers and motorcycles

George Singer began manufacturing motorised three-wheelers in 1901, followed by motorwheels which were fitted to bicycles.[3] Singer developed a 222 cc four-stroke single using an engine design bought from former Beeston employees Edwin Perks and Frank Birch.

A unique feature of the Perks-Birch design was that the engine, fuel tank, carburettor and low-tension magneto were all housed in a two-sided cast alloy spoked wheel. It was probably the first motor bicycle to be provided with magneto ignition. The design was used by Singer & Co in the rear wheel and then the front wheel of a trike.

In 1904 he developed a range of more conventional motorcycles which included 346 cc two strokes and, from 1911, side-valve models of 299 cc and 535 cc. In 1913 Singer & Co offered an open-frame ladies model.[4]

Singer & Co stopped building motorcycles at the outbreak of the First World War.[5]

- Motorcycle racing

In 1909 Singer & Co built a series of racers and roadsters and entered several bikes in races, including the Isle of Man Senior TT in 1914.[4] George E. Stanley broke the one-hour record at Brooklands race track on a Singer motorcycle in 1912, becoming the first ever rider of a 350 cc motorcycle to cover over 60 miles (97 km) in an hour.[3]

Motor cars

Singer made their first four-wheel car in 1905. It was designed by Scottish engineer Alexander Craig and was a variant of a design he had done for Lea-Francis having a 2-cylinder 1853 or 2471 cc engine.[6]

The first Singer-designed car was the 4-cylinder 2.4-litre 12/14 of 1906. The engine was bought in from Aster. For 1907 the Lea-Francis design was dropped and a range of two-, three- and four-cylinder models using White and Poppe engines launched. The Aster engined models were dropped in 1909 and a new range of larger cars introduced. All cars were now White and Poppe powered. In 1911 the first big seller appeared with the four-cylinder 1100 cc Ten with Singer's own engine. The use of their own power plants spread through the range until by the outbreak of the First World War all models except the low-volume 3.3-litre 20 hp were so equipped.

Lionel Martin made his first ascent of Aston Hill in that hill-climbing competition in a tuned Singer 10 car, 4 April 1914. He repeated his success a month later, and when he first registered his own car the following year he called it an Aston Martin.

The Ten continued after the war, with a redesign in 1923 including a new overhead-valve engine. Six-cylinder models were introduced in 1922. In 1921 Singer took over another Coventry car maker Coventry Premier and continued to sell a range of cars under that name until 1924.[6] Calcott Brothers was purchased in 1926.[6] For 1927 the Ten engine grew to 1300 cc and a new light car with 850 cc overhead cam (ohc) engine, the big selling Junior was announced and at the same time the Ten became the Senior. By 1928 Singer was Britain's third largest car maker after Austin and Morris.[7]

During the 1920s Singer, restricted by a built-in site acquired other companies for factory space. In 1926 they made 9,000 cars. In 1929 with seven factories and 8,000 employees they produced 28,000 cars though having just 15% they trailed far behind Austin and Morris which shared 60% of the market. Hampered by their new acquisitions, the cost of new machinery and a moving assembly line in their latest acquisition Singer's offerings were eclipsed by new models from their rivals; Austin, Morris and Hillman and then from 1932 the new Ford Model Y.[1]

The range continued in a very complex manner using developments of the ohc Junior engine first with the Nine (two bearing crank), the 14/6 and the sporty 1½-litre in 1933. The Nine became the Bantam in 1935. Externally the Bantam was very similar to the Morris Eight, had a three-bearing crankshaft and it was the first Singer to be fitted with a synchromesh gearbox, albeit with only three forward gears.[8] The first Bantams had two-bearing crankshafts & 972cc. In 1938 the three-bearing O.H.C. engine of 1074cc [9HP] was introduced, the three speed gearbox only had synchro between 2nd and top. [9]

The 1935 Tourist Trophy race in the Isle of Man was a disaster, three of the four team Singer 9 cars crashed because of steering failures before the fourth was withdrawn. In May 1936 W E Bullock who had been managing director from 1919 together with his son, general manager from 1931, resigned following criticism from the shareholders at their annual general meeting. No longer viable Singer & Co Limited was dissolved in December 1936 and what had been its business was transferred to a new company – Singer Motors Limited.[10]

_(15476334908).jpg) Ten

Ten

1919- Junior 8

1927  Senior 10/26 1308 cc

Senior 10/26 1308 cc

tourer 1927- Senior-Six 1792 cc

1930  Silent-Six 2160 cc

Silent-Six 2160 cc

Continental sports saloon, 1933 Nine Sports 972 c.c.

Nine Sports 972 c.c.

helmet wings, 1933- Eleven saloon 1384 cc 1934

1½-Litre

1½-Litre

Le Mans 2-Seater Sports 1934

Singer Motors Limited

Bantam Nine 4-door

Bantam Nine 4-door

972 c.c.

1936 Bantam Nine tourer

Bantam Nine tourer

972 c.c.

1936_(15476914220).jpg) Bantam Nine saloon

Bantam Nine saloon

1074 c.c.

1939.jpg) Bantam Nine van

Bantam Nine van

1074 c.c.

1939 (Bantam) Nine Roadster

(Bantam) Nine Roadster

1074 c.c.

1939

From 1938 to 1955 Singer Motors Ltd supplied new engines and gearboxes for fitment to HRG Engineering Company's sports cars at Tolworth,Surrey.

After the Second World War the new Roadster and the Ten and Twelve saloons all returned to production with little change. In 1948 the SM1500 with independent front suspension and a separate chassis was announced, still using the SOHC 1500cc engine. It was, however, expensive at £799, and failed to sell well as Singer's rivals also got back into full production. The SM1500 was given a traditional radiator grille and renamed the Hunter in 1954. The Hunter was briefly available with an HRG-designed twin overhead-cam version of the engine but few were made. In the December, 2011 edition of Automobile Magazine a 1954 Singer SM1500 was compared to an MG-TD, finding the Singer the superior roadster.[11]

- Nine Roadster

(North America) 1948  Super Ten

Super Ten

1946 Super Twelve

Super Twelve

1949- SM1500

1948–54  Hunter

Hunter

1954–56

Rootes Group

By 1955 the business was in financial difficulties and the Rootes Brothers bought it the following year. They had first handled Singer sales just before the First World War. The Singer brand was absorbed into their Rootes Group which had been an enthusiastic exponent of Badge engineering since the early 1930s. The next Singer car, the Gazelle, was a Hillman Minx variant that retained the pre-war designed Singer ohc engine for the I and II versions but this too went in 1958 when the IIA was given the Hillman Minx push-rod engine. The Vogue, which ran alongside the Minx/Gazelle from 1961, was based on the Hillman Super Minx with differing front end styling and more luxurious trim.

.jpg) Gazelle Mark V

Gazelle Mark V Gazelle Convertible 1960

Gazelle Convertible 1960 Vogue 1962

Vogue 1962 Chamois 1965–70

Chamois 1965–70 Vogue 1968

Vogue 1968

By 1970, Rootes were beginning to struggle financially. They had been acquired by the American Chrysler corporation, and founder Sir William had died in 1964. In April 1970, as part of a rationalisation process, the last Singer rolled off the assembly line, almost 100 years after George Singer built the first cycle.[12] The last car to carry the Singer name was an upmarket version of the rear engined Hillman Imp called the Chamois. With the take over of Rootes by Chrysler begun in 1964 and completed in 1967, many of the brands were to vanish and the Singer name disappeared forever in 1970. The site of the Singer factory in Coventry is now occupied by Singer Hall, a hall of residence for Coventry University.

Models

The main models produced[13] were:

e. & o.e.

| |

cylinders | cubic

capacity |

bore and

stroke |

tax

horsepower |

power output | years in

production |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

- World War I

| |

cylinders | cubic

capacity |

bore and

stroke |

tax

horsepower |

power output | years in

production |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

——————————————————————————————————————————————

——————————————————————————————————————————————

| |

cylinders | cubic

capacity |

bore and

stroke |

tax

horsepower |

power output | years in

production |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

1946–49 |

- World War II

| |

cylinders | cubic

capacity |

bore and

stroke |

tax

horsepower |

power output | years in

production |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

——————————————————————————————————————————————

- December 1955: Singer Motors joins Rootes Group[16]

——————————————————————————————————————————————

| |

cylinders | cubic

capacity |

bore and

stroke |

tax

horsepower |

power output | years in

production |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

1,494 cc (91 cu in) |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

74 bhp (55 kW; 75 PS) @ 5,000 rpm |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

See also

References

_Ltd.%2C_Coventry._Directors'_Report%2C_31_July%2C_1910.jpg)

- Kevin Atkinson The Singer Story, Cars, Commercial Vehicles, Bicycles, Motorcycles; Veloce Publishing ISBN 9781874105527

- 1 2 3 4 Anne Pimlott Baker, Bullock, William Edward (1877–1968), Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004

- ↑ "Advertisement for Singer bicycles and motor cycles, 1901.". Science & Society Picture Library. Retrieved 2011-06-06.

- 1 2 De Cet, Mirco (2005). Quentin Daniel, ed. The Complete Encyclopedia of Classic Motorcycles. Rebo International. ISBN 978-90-366-1497-9.

- 1 2 "Singer". Retrieved 2009-01-03.

- ↑ "Brief History of the Marque: Singer". Retrieved 2009-01-03.

- 1 2 3 Georgano, N. (2000). Beaulieu Encyclopedia of the Automobile. London: HMSO. ISBN 1-57958-293-1.

- ↑ Baldwin, N. (1994). A–Z of Cars of the 1920s. Devon, UK: Bay View Books. ISBN 1-870979-53-2.

- ↑ History of Singer Cars – Classic Motor History Classic Motor History

- ↑ Andreassen, David (2013). Book of the Bantam.

- 1 2 Scheme of Arrangement, The Times, Thursday, 10 December 1936; pg. 21; Issue 47554; col G

- ↑ David Zenlea (December 16, 2011). "Collectible Classic: 1939-1956 Singer Roadster". Automobile Magazine.

- ↑ History of Singer Cars Classic Motor History

- ↑ Kevin Atkinson, The Singer Story, Cars, Commercial Vehicles, Bicycles, Motorcycles; Veloce Publishing ISBN 9781874105527

- ↑ High Court of Justice, Chancery Division, The Times, Friday, 11 December 1936; pg. 31; Issue 47555; col D

- ↑ Dominion Motors advertisement for Singer Cars and Utilities, Sydney Morning Herald, Tuesday, 1 April 1952, page 8 Retrieved from trove.nla.gov.au on 19 July 2012

- ↑ Rootes To Take Over Singers Improved Offer Accepted, Vote After Warning On Bank Account The Times, Friday, 30 December 1955; pg. 8; Issue 53415; col B

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Singer vehicles. |

- Singer Owners' Club

- North American Singer Owners Club

- Singer Motors at DMOZ

- Automobilemag.com; Singer Motors

- Singer Senior 1927

- Singer Six 1929

- Singer Super Six 1931

- Youtube.com: "O'Toole and the blue Singer."