Wels catfish

| Wels catfish | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Actinopterygii |

| Order: | Siluriformes |

| Family: | Siluridae |

| Genus: | Silurus |

| Species: | S. glanis |

| Binomial name | |

| Silurus glanis Linnaeus, 1758 | |

| |

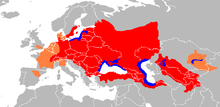

| Range of the wels catfish. Red: native occurrence. Blue: occurrence in coastal waters. Orange: introduced | |

The wels catfish (/ˈwɛls/ or /ˈvɛls/; Silurus glanis), also called sheatfish, is a large species of catfish native to wide areas of central, southern, and eastern Europe, in the basins of the Baltic, Black, and Caspian Seas. It has been introduced to Western Europe as a sport fish and is now found from the United Kingdom all the way east to Kazakhstan and China and south to Greece and Turkey. It is a scaleless freshwater fish recognizable by its broad, flat head and wide mouth. Wels catfish can live for at least fifty years.

Habitat

The wels catfish lives in large, warm lakes and deep, slow-flowing rivers. It prefers to remain in sheltered locations such as holes in the riverbed, sunken trees, etc. It consumes its food in the open water or in the deep, where it can be recognized by its large mouth. Wels catfish are kept in fish ponds as food fish.

Diet

Like most freshwater bottom feeders, the wels catfish lives on annelid worms, gastropods, insects, crustaceans, and fish. Larger specimens have been observed to eat frogs, mice, rats, aquatic birds such as ducks and can also be cannibalistic. According to a study published by researchers at the University of Toulouse, France in 2012,[1] individuals of this species in environments outside of their normal habitats have been observed lunging out of the water to feed on pigeons on land.[2] Out of all beaching behaviors observed and filmed in this study, 28% of them were successful in bird capture. Stable isotope analyses of catfish stomach contents using carbon 13 and nitrogen 15 revealed a highly variable dietary composition of terrestrial birds. This is likely the result of adapting their behavior to forage on novel prey in response to new environments upon its introduction to the Tarn River in 1983[3] since this type of behavior has not been reported before within the native range of this species.

_(13532570755).jpg)

Physical characteristics

The wels catfish's mouth contains lines of numerous small teeth, two long barbels on the upper jaw and four shorter barbels on the lower jaw. It has a long anal fin that extends to the caudal fin, and a small sharp dorsal fin relatively far forward. It relies largely on hearing and smell for hunting prey, but its eyes have a tapetum lucidum, providing the advantage of night vision, contrary to popular belief that the wels has poor eyesight. With its sharp pectoral fins, it creates an eddy to disorient its victim, which the predator sucks into its mouth and swallows whole. The skin is very slimy. Skin colour varies with environment. Clear water will give the fish a black color, while muddy water will often tend to produce green-brown specimens. The underside is always pale yellow to white in colour. Albinistic specimens are known to exist and are caught occasionally. The wels swims by undulating its long, muscular tail in a wave-like action, similar to crocodilians. They can also swim backwards.

%2C_%D0%A1%D1%8B%D1%80%D0%B4%D0%B0%D1%80%D0%B8%D1%8F%2C_%D0%91%D0%B0%D0%B9%D2%9B%D0%BE%D2%A3%D1%8B%D1%80.jpg)

Size

With a possible total length up to 5 m (16 ft) and a maximum weight of over 300 kg (660 lb),[4] the wels catfish is the largest true freshwater fish (as opposed to anadromous or catadromous) in its region (Europe and parts of Asia). However, such lengths are rare and were hard to prove during the last century, but there is a somewhat credible report from the 19th century of a wels catfish of this size. Brehms Tierleben cites Heckl's and Kner's old reports from Danube about specimens 3 m (9.8 ft) long and 200–250 kg (440–550 lb) in weight, and Vogt's 1894 report of a specimen caught in Lake Biel which was 2.2 m (7 ft 3 in) long and weighed 68 kg (150 lb).[5] In 1856, K. T. Kessler wrote about specimens from the Dnieper River which were over 5 m (16 ft) long and weighed up to 400 kg (880 lb).[6]

Most wels catfish are mainly about 1.3–1.6 m (4 ft 3 in–5 ft 3 in) long; fish longer than 2 m (6 ft 7 in) are normally a rarity. At 1.5 m (4 ft 11 in) they can weigh 15–20 kg (33–44 lb) and at 2.2 m (7 ft 3 in) they can weigh 65 kg (143 lb).

Only under exceptionally good living circumstances can the wels catfish reach lengths of more than 2 m (6 ft 7 in), as with the record wels catfish of Kiebingen (near Rottenburg, Germany), which was 2.49 m (8 ft 2 in) long and weighed 89 kg (196 lb). This giant was surpassed by some even larger specimens from Poland (2,61 m. 109 kg.), the former Soviet states (the Dnieper River in Ukraine, the Volga River in Russia and the Ili River in Kazakhstan), France, Spain (in the Ebro), Italy (in the Po and Arno), and Greece, where this fish was released a few decades ago. Greek wels grow well thanks to the mild climate, lack of competition, and good food supply. The largest accurate weight was 144 kg (317 lb) for a 2.78 m (9 ft 1 in) long specimen from the Po Delta in Italy.[7]

Exceptionally large specimens are rumored to attack humans in rare instances, a claim investigated by extreme angler Jeremy Wade in an episode of the Animal Planet television series River Monsters following his capture of three fish, two of about 66 kg (145 lb) and one of about 73 kg (160 lb), of which two attempted to attack him following their release. A report in the Austrian newspaper Der Standard on 5 August 2009, mentions a wels catfish dragging a fisherman near Győr, Hungary, under water by his right leg after the man attempted to grab the fish in a hold. The man barely escaped with his life from the fish, which must have weighed over 100 kg (220 lb), according to the fisherman.[8]

Ecology

There are concerns about the ecological impact of introducing the wels catfish to non-native regions. These concerns take into account the situation in Lake Victoria in Africa, where Nile perch were introduced and rapidly caused the extinction of numerous indigenous species. This severely impacted the entire lake, destroying much of the original ecosystem. The introduction of foreign species is almost always a burden on the affected ecosystem. Following the introduction of wels catfish, some fishes' numbers are in clear and rapid decline. Since its introduction in the Mequinenza Reservoir in 1974, it has spread to other parts of the Ebro basin, including its tributaries, especially the Segre River. Some endemic species of Iberian barbels, genus Barbus in the Cyprinidae, were once abundant especially in the Ebro river but due to competition from and predation by wels catfish have since disappeared in the middle channel Ebro. The ecology of the river has also changed, as there is now a major growth in aquatic vegetation such as algae. Barbel species from mountain stream tributaries of the Ebro that wels catfish have not colonized are not affected.

Breeding

The female produces up to 30,000 eggs per kilogram of body weight. The male guards the nest until the brood hatches, which, depending on water temperature, can take from three to ten days. If the water level decreases too much or too fast the male has been observed to splash the eggs with its tail in order to keep them wet.

As a food fish

Only the flesh of young Silurus glanis specimens is valued as food. It is palatable when the catfish weighs less than 15 kg (33 lb). Larger than this size, the fish is highly fatty and not recommended for consumption.

Related species

- Aristotle's catfish (Silurus aristotelis) from Greece, the only other native European catfish species beside Silurus glanis.

- Amur catfish (Silurus asotus), introduced to European rivers

- Giant lake biwa catfish (Silurus biwaensis) from Japan endemic to Lake Biwa.

- Silurus soldatovi from Russia

References

- ↑ Sieczkowski, Cavan. "Catfish Hunt Pigeons: Fish Catch Birds On Land In Display Of Adaptive Behavior (VIDEO)". The Huffington post. Retrieved 16 March 2017.

- ↑ Cucherousset, J.; Boulêtreau, S. P.; Azémar, F. D. R.; Compin, A.; Guillaume, M.; Santoul, F. D. R. (2012). Steinke, Dirk, ed. ""Freshwater Killer Whales": Beaching Behavior of an Alien Fish to Hunt Land Birds". PLoS ONE. 7 (12): e50840. PMC 3515492

. PMID 23227213. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0050840.

. PMID 23227213. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0050840. - ↑ Yong, Ed. "The catfish that strands itself to kill pigeons". Discover Magazine. Retrieved 16 March 2017.

- ↑ Froese, Rainer and Pauly, Daniel, eds. (2016). "Silurus glanis" in FishBase. February 2016 version.

- ↑ Brehm, Alfred; Brehms Tierleben II - Fish, Amphibians, Reptiles 1

- ↑ Mareš, Jaroslav; Legendární příšery a skutečná zvířata, Prague, 1993

- ↑ Wood, Gerald C. (1982). The Guinness book of animal facts and feats. Enfield, Middlesex: Guinness Superlatives. ISBN 0-85112-235-3.

- ↑ Der Standard, 2009-08-05. Waller-Wrestling im ungarischen Fischerteich. Retrieved 2009-08-06. (in German)

Additional reading

- World Conservation Monitoring Centre (1996). "Silurus glanis". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2006. International Union for Conservation of Nature. Retrieved 9 May 2006.

- "Silurus glanis". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved 19 March 2006.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Silurus glanis. |

| Wikispecies has information related to: Silurus glanis |

- This article includes information translated out of the German and French Wikipedias.