Silkville, Kansas

|

Silkville | |

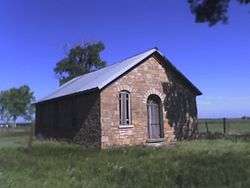

Silkville's school house | |

| |

| Location | Williamsburg Township, Franklin County, Kansas |

|---|---|

| Nearest city | Williamsburg, Kansas |

| Coordinates | 38°27′00″N 95°29′21″W / 38.45000°N 95.48917°WCoordinates: 38°27′00″N 95°29′21″W / 38.45000°N 95.48917°W |

| Area | 6 acres (2.4 ha) |

| Built | 1870 |

| NRHP Reference # | 72000504 |

| Added to NRHP | December 15, 1972 |

Silkville is a ghost town in Williamsburg Township, Franklin County, Kansas, United States. Its elevation is 1,161 feet (354 m), and it is located at 38°27′0″N 95°29′21″W / 38.45000°N 95.48917°W (38.4500149, -95.4891477),[1] along U.S. Route 50 southwest of Williamsburg.[2]

The settlement was founded in the late 1800s by a Frenchman named Ernest de Boissière, who was a believer in Charles Fourier's idea of a utopian socialism. Silkville was a sericulture-based settlement, and remuneration was based on the proportion of production for each settler. Silkville's silk was praised at the Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia in 1876, but loss of settlers and difficulty in selling the silk resulted in the settlements collapse. Today, only a few buildings remain.

History

The settlement was established in 1870 by Frenchman Ernest de Boissière. Because Boissière had been born into a noble family and had political inclinations—which were heavily inspired by the specific socialist philosophy of Charles Fourier—opposed by France's then-ruler Napoleon III, he was forced to flee.[3][4] Boissière first settled in New Orleans, but soon received heavy criticism for his decision to financially support orphaned black children.[4] He then decided to move to Kansas; he concluded that the state afforded him both the potential to practice his political ideas and create the type of community he desired. Boissière then purchased between 3000 and 3500 acres of land in the county from the Kansas Educational Association of the Methodist Episcopal Church in 1869 and went about setting up his intentional settlement.[3][4]

Silkville—which went under myriad different names, including Kansas Cooperative Farm, Prairie Home, and Valeton—was intended to be a Fourierian utopian commune that survived via silk production, and Boissière planted thousands of mulberry trees so that his silkworms could survive.[3][5] Boissière initially structured the system so that remuneration was based on the proportion of production for each settler, and, upon its founding, 40 French emigrants settled at the colony, each paying 100 dollars to be a part of the commune.[3][4] In 1875, Charles Sears, a friend of Boissière's, moved to Silkville, and his arrival was a boon for the settlement's sericulture. The following year, Boissière's silk was lauded at the Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia. Despite this critical reception, Silkville struggled to make money, largely because it was competing with comparatively cheaper fabrics imported from Asia, and because Boissière refused to use cost-effective American dyes.[6]

Although the community initially prospered, many members left.[3] Most, when they had arrived, spoke only French, but soon they learned English and began to assimilate into mainstream society. Many immigrants also learned that for 100 dollars—the amount that they had pledged to live in the settlement—they could buy their own land.[7] To compensate Boissière, shifted production towards butter and cheese, and later stock raising. And while this was fairly successful for a while, the community eventually collapsed and dispersed. The property was given to the Independent Order of Odd Fellows for use as an orphanage. Financial reasons compelled the Order to give up the property, and after a long court battle, it passed into the hands of lawyers from Topeka.[8]

Remains

Today, little remains of Silkville. Many of the original buildings were destroyed by a 1916 fire, and only three stone structures survive: the settlement's school house, and two barns.[3] The original chateau that Boissiere constructed—which, at the time of its construction cost US$10,000—was destroyed in the aforementioned fire, and a modern home was built over the west end of the ruin, utilizing some of the stone from the original.[9] One of the modern day barns was once the settlement's cocoonery, although it was reduced to a one-level building after a tornado damaged the top floor.[7] In 1972, these buildings were added to the National Register of Historic Places because of their significance in the history of Kansas.[10] The aspects of the community seen as most significant historically were its nature as an intentional community and its practice of sericulture.[11]

References

- ↑ U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Silkville, Kansas United States Geological Survey. Retrieved September 28, 2015.

- ↑ DeLorme 2009, p. 52.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Pankratz 1972, p. 2.

- 1 2 3 4 Tollefson 2015, p. 80.

- ↑ Richards, Catherine Jane; Barker, Deborah. "Southwest Franklin County". Franklin County Historical Society. Retrieved March 22, 2015.

- ↑ Tollefson 2015, p. 83.

- 1 2 Tollefson 2015, p. 84.

- ↑ Pankratz 1972, pp. 3, 5.

- ↑ Pankratz 1972, pp. 2–3.

- ↑ "Silkville". National Park Service. Retrieved September 28, 2015.

- ↑ Pankratz 1972, p. 5.

Bibliography

- Kansas Atlas & Gazetteer. Yarmouth: DeLorme. 2009. ISBN 9780899333427.

- Pankratz, Richard (May 15, 1972). "National Register of Historic Places Inventory/Nomination: Silkville" (PDF). National Park Service. Retrieved September 28, 2015.

- Tollefson, Julie (Spring 2015). "The Failed Silk Revolution". Lawrence Magazine. Sunflower Publishing. Retrieved September 28, 2015.

Further reading

- Fitzgerald, Daniel (1988). "Silkville". Ghost Towns of Kansas. University Press of Kansas. ISBN 9780700603688.

- "Mons. E.V. Boissiere's Silk Factory — A Magnificent Enterprise". Ottawa Journal. June 1, 1871.

- Nordhoff, Charles (1875). The Communistic Societies of the United States. New York City: Harper. pp. 375–382. ISBN 9781406550412.