Siege of Málaga (1487)

Coordinates: 36°43′08″N 4°25′12″W / 36.719°N 4.42°W

| Siege of Málaga (1487) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Reconquista | |||||||

Alcazaba of Málaga, built by the Hammudid dynasty in the 11th century | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

and | ||||||

Málaga Location in Spain | |||||||

The Siege of Málaga (1487) was an action during the Reconquest of Spain in which the Catholic Monarchs conquered the city of Málaga from the Muslims. The siege lasted about four months.[1] It was the first conflict in which ambulances, or dedicated vehicles for the purpose of carrying injured persons, were used.[2][lower-alpha 1]

Background

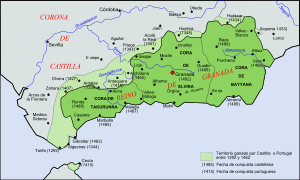

Málaga was the main objective of the 1487 campaign by the Catholic Monarchs against the Emirate of Granada, which had been steadily losing territory to the Christian forces.[3] King Ferdinand II of Aragon left Córdoba with an army of 20,000 horsemen, 50,000 laborers and 8,000 support troops. This contingent joined the artillery commanded by Francisco Ramírez de Madrid that left Écija. The army decided to first attack Vélez-Málaga, and then continue west to Malaga.[1] Nasrid spies gave word of the movements of the Christians, and the inhabitants of Vélez fled to the mountains and the Bentomiz castle.

The Spanish reached Vélez-Málaga on 17 April 1487 after a slow advance through difficult country. A few days later the lighter siege engines arrived. It had proved impossible to move the heavier ones along the poor roads.[4] Muhammed XIII, Sultan of Granada (El Zagal) made an attempt to relieve Vélez, but was forced to retreat to Granada by the superior forces of the marquis of Cadiz. On his arrival there he found that he had been overthrown in favor of his nephew Abdallah Muhammad XII. Seeing no hope of relief, Vélez capitulated on 27 April 1487 on condition that the lives of the people would be spared, and they would keep their property and religion. Smaller places also surrendered along the road to Málaga, the next objective.[5]

City of Malaga

The Moorish city of Mālaqa was the second city in the emirate after Granada itself, a major trading port on the Mediterranean.[5] The city was prosperous, with elegant architecture, gardens and fountains. The city was surrounded by fortifications, which were in good condition. Above it was the citadel, the Alcazaba of Málaga, connected via a covered way with the impregnable fortress of Gibralfaro. A land-side suburb was also ringed by a strong wall. Towards the sea were orchards of olives, oranges and pomegranates, and vineyards from whose grapes the sweet fortified Malaga wine, an important export, was made.[6]

The city was well-supplied with artillery and ammunition. In addition to the normal garrison it contained volunteers from other towns in the regions and a corps of Gomeres, experienced and disciplined African mercenaries. Hamet el Zegrí, the former defender of Ronda, was in command of the defense.[6][lower-alpha 2]

Siege (7 May – 13 August 1487)

While still at Vélez, Ferdinand attempted to negotiate a surrender on good terms, but his offers were refused by Hamet el Zegrí. Ferdinand left Velez on 7 May 1487 and advanced along the coast to Bezmiliana, about six miles from Málaga, where the road led between two heights defended by the Muslims.[6] A fight ensued that continued until evening, when the Christians managed to turn the position and the Muslims retreated to the Gibralfaro fortress. The landward height was converted into a Christian strong point, and they began construction of works encircling the city. These were either a trench and palisade, or an earth embankment where the ground was too rocky for excavation. A fleet of armed ships, galleys and caravels placed in the harbor cut off all access to the city from the sea.[7]

The first Christian attack was against the landward suburb. They breached the wall, and after strong resistance the Muslims were driven back into the city.[8] King Ferdinand II sent an expedition to the ruins of Algeciras to retrieve stone balls used in the Siege of Algeciras (1342–44) so they could be used against Málaga.[9][10] Queen Isabella joined her husband, accompanied by her court and by various high clergymen and nobles, a move that helped to boost morale.[8]

The Muslims kept up fire from the city on the Christian lines, and made repeated sallies, sometimes in strength. There were also attempts to relieve the city. In one case El Zagal sent a body of cavalry from Guadix, but a stronger force sent by Abdallah intercepted and defeated it. Abdallah followed up by sending costly gifts to the Catholic monarchs and assuring them of his friendly disposition. In return, the monarchs agreed to leave his subjects in peace and to allow non-military trade between Granada and Spain.[11] Málaga began to run short of food supplies. The Christians received two Flemish transports with military supplies sent by Maximilian I, Holy Roman Emperor.[12]

Ferdinand had intended to starve the city out, but became impatient with the delays and began construction of mobile siege towers that could be used to bridge the walls, and mines to enter the city from below or to undermine the walls. The Muslims attacked and destroyed the towers, counter-mined and drove out the Christians, and sent out armed vessels against the Christian fleet.[13]

However, after three months the Christians managed to take possession of an outlying tower attached with a bridge of four arches to the city wall, a key point from which to advance into the city. By this time the Malagans had run out of stores of food and had been reduced to the extremes of eating dogs and cats, eating the leaves of vines and palms and chewing hides. Seeing their extreme suffering, Hamet el Zegrí eventually agreed to withdraw with his forces to the Gibralfaro, and let the population make terms with the Christians.[14]

Capitulation (13–19 August 1487)

After unsuccessful attempts to negotiate terms, the representatives of the city eventually capitulated without conditions, throwing themselves on Ferdinand's mercy.[14] The city surrendered on 13 August 1487. The citadel held out until 18 August 1487 when its leader, the merchant Ali Dordux, surrendered on the basis that his group of twenty-five families would be allowed to stay as Mudéjars. The monarchs entered triumphantly on 18 August 1487.[15] The fortress of the Gibralfaro, under the command of Hamet el Zegrí, surrendered the next day.[16]

Aftermath

The conquest of Málaga was a harsh blow to the Nasrid kingdom of Granada, which lost its principal seaport. King Ferdinand II of Aragon decided to apply an exceptional punishment for the prolonged resistance. The whole population was condemned to slavery or death, other than the group led by Ali Dordux. Hamet el Zegrí was executed.[17] The survivors, numbering from 11,000 to 15,000 excluding the foreign mercenaries, were enslaved and their property confiscated. Some were sent to Morocco in exchange for Christian captives, some were sold to defray the costs of the campaign, and some were distributed as gifts.[18]

The task of reorganizing the territory was given to García Fernández Manrique, who had captured the fortress, and to Juan de la Fuente, two experienced administrators. Manrique made use of the help of Ali Dordux.[19] Land was given in payment to the troops that accompanied the conquistadors. Between 5,000 and 6,000 Christians from Extremadura, León, Castile, Galicia and the Levant repopulated the province, of whom about a thousand settled in the capital.

Notes

- ↑ The ambulances arranged by Queen Isabella of Castile were large bedded wagons that were used to carry wounded soldiers to tent hospitals far from the lines. The care that could be provided was limited, but the attempt at care would have been good for morale.[2]

- ↑ The army had taken the city of Ronda by storm on 22 May 1485. The city's commander (arraez), the Moorish chieftain Hamet el Zegrí (Hamad al-Tagri), had refused Ferdinand and Isabella's offer to accept his vassalage, and had moved to Mālaqa, where he led the Muslim resistance.

References

- 1 2 Bernáldez & Gabriel y Ruíz de Apodaca 1870, p. 224.

- 1 2 Kuehl 2002, p. 81.

- ↑ Prescott 1854, p. 205.

- ↑ Prescott 1854, p. 211.

- 1 2 Prescott 1854, p. 212.

- 1 2 3 Prescott 1854, p. 213.

- ↑ Prescott 1854, p. 214.

- 1 2 Prescott 1854, p. 215.

- ↑ Del Pulgar 1780, p. 304.

- ↑ Torremocha Silva 2004, p. s1.3.

- ↑ Prescott 1854, p. 216.

- ↑ Prescott 1854, pp. 217–218.

- ↑ Prescott 1854, p. 218.

- 1 2 Prescott 1854, p. 219.

- ↑ Martínez de la Rosa 1834, p. 115.

- ↑ Prescott 1854, p. 221.

- ↑ Mata Carriazo y Arroquia 1971, p. 346.

- ↑ Prescott 1854, pp. 222–223.

- ↑ Lunenfeld 1987, p. 142.

Sources

- Bernáldez, Andrés; Gabriel y Ruíz de Apodaca, Fernando (1870). Historia de los reyes católicos C. Fernando y Doña Isabel. Impr. que fué de J. M. Geofrin. Retrieved 2013-02-21.

- Del Pulgar, Hernando (1780). Crónica de los Señores Reyes Católicos Don Fernando y Doña Isabel de Castilla y de Aragón. Imprenta de Benito Monfort.

- Kuehl, Alexander E. (2002-09-01). Prehospital Systems and Medical Oversight. Kendall Hunt. p. 81. ISBN 978-0-7872-7071-1. Retrieved 2013-02-22.

- Lunenfeld, Marvin (1987). Keepers of the City: The Corregidores of Isabella of Castile, 1474–1504. Cambridge University Press. p. 142. ISBN 978-0-521-32930-9. Retrieved 2013-02-22.

- Martínez de la Rosa, Francisco (1834). Hernan Perez del Pulgar, el de las hazañas: bosquejo histórico. Tomas Jordan. p. 115. Retrieved 2013-02-21.

- Mata Carriazo y Arroquia, Juan (1971). En la frontera de Granada. Universidad de Sevilla. p. 346. ISBN 978-84-338-2842-2. Retrieved 2013-02-21.

- Prescott, William Hickling (1854). History of the reign of Ferdinand and Isabella, the Catholic, of Spain. p. 211. Retrieved 2013-02-22.

- Torremocha Silva, Antonio (2004). "Cerco y defensa de Algeciras: el uso de la pólvor". Centro de estudios moriscos de Andalucía.