Siege of Cuzco

| Siege of Cuzco | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Spanish conquest of Peru | ||||||||

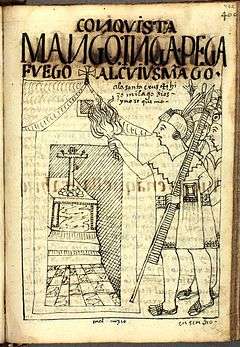

The siege of Cuzco according to Felipe Guaman Poma de Ayala | ||||||||

| ||||||||

| Belligerents | ||||||||

|

| Remnants of the Inca Empire | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | ||||||||

|

Hernando Pizarro (POW) Gonzalo Pizarro (POW) Juan Pizarro II † Francisco Pizarro |

Diego de Almagro Rodrigo Orgóñez |

Manco Inca Yupanqui Cahuide† | ||||||

| Strength | ||||||||

|

30,000 Indios auxiliares 190 Spaniards Later +300 Spaniards under F. Pizarro[1] | 700 Spaniards (as for early 1537) | 100,000 to 200,000 Inca warriors | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | ||||||||

| Unknown | Unknown, but low | Unknown | ||||||

The Siege of Cuzco (May 6, 1536 – March 1537) was the siege of the city of Cusco by the army of Sapa Inca Manco Inca Yupanqui against a garrison of Spanish conquistadors and Indian auxiliaries led by Hernando Pizarro in the hope to restore the Inca Empire (1438-1533). The siege lasted ten months and was ultimately unsuccessful.

Background

A Spanish expedition led by Francisco Pizarro had captured the Inca capital of Cusco on November 15, 1533 after defeating an Inca army headed by general Quisquis.[2] The following month, the conquistadors supported the coronation of Manco Inca as Inca emperor to facilitate their control over the empire.[3] Real power rested with the Spaniards who frequently humiliated Manco Inca and imprisoned him after an attempted escape in November 1535.[4] After his release in January 1536, Manco Inca left Cusco on April 18 promising the Spanish commander, Hernando Pizarro, to bring back a large gold statue when in fact he was already preparing a rebellion.[5]

Siege

Having realized their mistake, Hernando Pizarro led an expedition against Manco Inca's troops, which had gathered in the nearby Yucay Valley; the attack failed as the Spaniards had severely underestimated the size of the Inca army.[6] The Inca emperor did not attack Cusco at once, instead he waited to assemble his full army estimated at between 100,000 and 200,000 men strong around the city (some sources suggest numbers as low as 40,000); against them there were 190 Spaniards, 80 of them horsemen, and several thousand Indian auxiliaries.[7] The siege started on May 6, 1536 with a full-scale attack towards the main square of the city; the Inca army succeeded in capturing most of the city while the Spaniards took refuge in two large buildings near the main plaza.[8] The conquistadors fended off Inca attacks from these constructions and mounted frequent raids against their besiegers.[9]

To relieve their position, the Spaniards decided to assault the walled complex of Saksaywaman which served as the main base of operations for the Inca army. Fifty horsemen, led by Juan Pizarro, and accompanied by Indian auxiliaries broke through the Inca army files, turned around and attacked Sacsayhuamán from outside the city. During the frontal assault against the building's large walls, a stone struck Juan Pizarro in the head; he died days later from the injury sustained. The following day, the Spaniards resisted several Inca counterattacks and mounted a renewed assault at night using scaling ladders. In this way, they captured the terrace walls of Sacsayhuamán while the Inca army held on to the two tall towers of the complex. The Inca commanders, Paucar Huaman and the high priest or Willaq Umu, decided to leave the confinement of the towers and fight their way towards Calca, the site of Manco Inca's headquarters, to bring back reinforcements. The attempt was successful and the towers were left under the command of Titu Cusi Gualpa, an Inca nobleman. Despite Titu's fierce resistance, the Spaniards and their auxiliaries stormed the towers so that when the Inca commanders returned, Saksaywaman was firmly under their control.[10]

The capture of Saksaywaman eased the pressure on the Spanish garrison at Cusco; the fighting now turned in a series of daily skirmishes interrupted only by the Inca religious tradition of halting attacks during the new moon.[11] During this period, the Spaniards successfully implemented terror tactics to demoralize the Inca army, which included an order to kill any woman caught and cutting off the hands of captured men.[12] Encouraged by their successes, Hernando Pizarro led an attack against Manco Inca's headquarters which were now at Ollantaytambo, further away from Cusco. Manco Inca defeated the Spanish expedition at the Battle of Ollantaytambo by taking advantage of the fortifications and the difficult terrain around the site.[13] The Spanish garrison had more success with several raids to gather food from regions near Cusco; these incursions allowed them to replenish their almost exhausted provisions.[14] Meanwhile, Manco Inca tried to capitalize on his success at Ollantaytambo with a renewed assault on Cusco, but a Spanish cavalry party had a chance encounter with the Inca army thus ruining any hope of surprise. That same night the Spaniards mounted a full-scale attack which achieved complete surprise and inflicted severe casualties on Manco Inca's troops.[15]

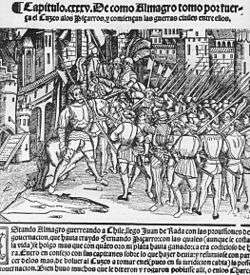

After 10 months of vicious fighting in Cusco, with low morale playing a factor, Manco Inca decided to raise the siege at Cusco and withdraw to Ollantaytambo and then Vilcabamba, where he established the small Neo-Inca State. It is suggested by some that by this action he threw away his only real chance to rebuff the Spaniards from the lands of the Inca Empire, but it was probably the only realistic choice he had considering the arrival of Spanish reinforcements from Chile led by Diego de Almagro. Upon facing victory and the availability of expanding his own reign into Peru, Almagro seized the city once having achieved victory for Spain and had Hernando and Gonzalo imprisoned. Gonzalo escaped, to later face Almagro in a personal triumph at the Battle of Las Salinas.[16]:246–249,256–260

Notes

- ↑ Jay O. Sanders. "The Great Inca Rebellion". Retrieved 18 July 2010.

- ↑ Hemming, The conquest, pp. 115.

- ↑ Hemming, The conquest, pp. 123–125.

- ↑ Hemming, The conquest, pp. 178–180.

- ↑ Hemming, The conquest, pp. 181–182.

- ↑ Hemming, The conquest, pp. 184–185.

- ↑ Hemming, The conquest, pp. 185–186.

- ↑ Hemming, The conquest, pp. 187–188.

- ↑ Hemming, The conquest, pp. 189–190.

- ↑ Hemming, The conquest, pp. 192–196.

- ↑ Hemming, The conquest, p. 197.

- ↑ Hemming, The conquest, pp. 198–199.

- ↑ Hemming, The conquest, pp. 207–209.

- ↑ Hemming, The conquest, pp. 210–211.

- ↑ Hemming, The conquest, pp. 211–212.

- ↑ Prescott, W.H., 2011, The History of the Conquest of Peru, Digireads.com Publishing, ISBN 9781420941142