Sidney Mintz

| Sidney Mintz | |

|---|---|

| Born |

November 16, 1922 Dover, New Jersey |

| Died |

December 27, 2015 (aged 93)[1] Plainsboro, New Jersey |

| Residence | Cockeysville, Maryland |

| Citizenship | United States |

| Fields | Economic anthropology, Food history |

| Institutions |

Yale University Johns Hopkins University |

| Alma mater |

Brooklyn College (B.A.) Columbia University (Ph.D.) |

| Thesis | Cañamelar: The Contemporary Culture of a Rural Puerto Rican Proletariat (1951) |

| Doctoral advisors | Ruth Benedict • Julian Steward |

| Influences | Ruth Benedict • Alexander Lesser • Eric Wolf • Eric Williams |

| Notable awards |

Huxley Memorial Medal (1994) AAA Distinguished Lecturer (1996) Franz Boas Award for Exemplary Service to Anthropology (2012) |

| Spouse | Jacqueline Wei Mintz |

|

Website sidneymintz | |

| Anthropology |

|---|

|

Key theories |

|

Lists

|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Economic, applied, and development anthropology |

|---|

|

Provisioning systems |

|

Case studies

|

| Social and cultural anthropology |

Sidney Wilfred Mintz (November 16, 1922 – December 27, 2015) was an anthropologist best known for his studies of the Caribbean, creolization, and the anthropology of food. Mintz received his PhD at Columbia University in 1951 and conducted his primary fieldwork among sugar-cane workers in Puerto Rico. Later expanding his ethnographic research to Haiti and Jamaica, he produced historical and ethnographic studies of slavery and global capitalism, cultural hybridity, Caribbean peasants, and the political economy of food commodities. He taught for two decades at Yale University before helping to found the Anthropology Department at Johns Hopkins University, where he remained for the duration of his career. Mintz' history of sugar, Sweetness and Power, is considered one of the most influential publications in cultural anthropology and food studies.[2][3]

Early life and education

Mintz was born in Dover, New Jersey,[4] to Fanny and Soloman Mintz. His father was a New York tradesman, and his mother was a garment-trade organizer for the Industrial Workers of the World.[5] Mintz studied at Brooklyn College, earning his B.A in psychology in 1943.[5] After enlisting in the US Army Air Corps for the remainder of World War II, he enrolled in the doctoral program in anthropology at Columbia University and completed a dissertation on sugar-cane plantation workers in Santa Isabel, Puerto Rico under the supervision of Julian Steward and Ruth Benedict.[2] While at Columbia, Mintz was one of a group of students who developed around Steward and Benedict known as the Mundial Upheaval Society.[2][5] Many prominent anthropologists such as Marvin Harris, Eric Wolf, Morton Fried, Stanley Diamond, Robert Manners, and Robert F. Murphy were among this group.

Career

Mintz had a long academic career at Yale University (1951–74) before helping to found the Anthropology Department at Johns Hopkins University. He has been a visiting lecturer at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, the École Pratique des Hautes Études and the Collège de France (Paris) and elsewhere. His work has been the subject of several studies.,[6][7][8][9] in addition to his reflections on his own ideas and fieldwork.[10][11] He was honored by the establishment of the annual Sidney W. Mintz Lecture in 1992.[12]

Mintz was a member of the American Ethnological Society and was President of that body from 1968 to 1969, a fellow of the American Anthropological Association and the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland. Mintz taught as a lecturer at City College (now City College of the City University of New York), New York City, in 1950, at Columbia University, New York City, in 1951, and at Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut between 1951 and 1974. At Yale, Mintz started as an instructor, but was Professor of Anthropology from 1963 to 1974. He also served as Professor of Anthropology at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, Maryland since 1974. Mintz was also a Visiting Professor at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in the 1964-65 academic year, a Directeur d'Etudes at the Ecole Pratique des Hautes Etudes in Paris in 1970-1971. He was a Lewis Henry Morgan Lecturer at the University of Rochester in 1972, a Visiting Professor at Princeton University in 1975-1976, a Christian Gauss Lecturer, 1978-1979, Guggenheim Fellow in 1957, a Social Science Research Council faculty research fellow, 1958-59. He was awarded a master's degree from Yale University in 1963, a Fulbright senior research award in 1966-67 and in 1970-71, a William Clyde DeVane Medal from Yale University in 1972 and was a National Endowment for the Humanities fellow, 1978-79. He died on December 26, 2015 at the age of 94, following severe head trauma resulting from a fall.[13]

Additional work and awards

Mintz has served as a consultant to various institutions including the Overseas Development Program, he has conducted field work in several countries, and he has been recognized with many awards including: Social Science Research Council Faculty Research Fellow, 1958–59; M.A., Yale University, 1963; Ford Foundation, 1957-62, and United States-Puerto Rico Commission on the Status of Puerto Rico, 1964–65; directeur d'etudes, Ecole Pratique des Hautes Etudes (Paris), 1970-71. He received the Franz Boas Award at the 2012 American Anthropological Association.

Training and influences

In his training Mintz was particularly influenced by Steward, Ruth Benedict (Mintz 1981a), and Alexander Lesser,[14] and by his classmate and co-author, Eric Wolf (1923-1999). Combining a Marxist and historical materialist approach with U.S. cultural anthropology, Mintz’s focus has been those large processes, starting in the fifteenth century, that marked the advent of capitalism and European expansion in the Caribbean, and the myriad institutional and political forms which buttressed that growth, on the one hand; and on the other, the local cultural responses to such processes. His ethnography centered on how these responses are manifested in the lives of Caribbean people. For Mintz, history did not erode differences to create homogeneity among regions, even while a capitalist world-system was emerging. Larger forces were always confronted by local responses that affected the cultural outcomes. Considering this relationship Mintz wrote:

It must be stressed that the integration of varied forms of labor-extraction within any component region addresses the way that region, as a totality, fits within the so-called world-system. There was give-and-take between the demands and initiatives originating with the metropolitan centers of the world-system, and the ensemble of labor forms typical of the local zones with which they were enmeshed....The postulation of a world-system forces us frequently to lift our eyes from the particulars of local history, which I would consider salutary. But equally salutary is the constant revisiting of events “on the ground,” so that the architecture of the world-system can be laid bare."[15]

This orientation found varied expressions in Mintz’s works, from his life history of “Taso” (Anastacio Zayas Alvarado), a Puerto Rican sugar worker,[16] to debating whether the Caribbean slave could be considered a proletarian.[17] He reasoned that, because slavery in the Caribbean was implicated in capitalism, slavery there was unlike Old World slavery; but also that because slave status meant unfree labor, Caribbean slavery was not a fully capitalistic labor-form for the extraction of surplus value. There were other contradictions: Caribbean slaves were legally defined as property, but often owned property; though slaves produced wealth for their owners, they also reproduced their labor through “proto-peasant” agriculture and market activities, reducing long-term supply costs for the owners. The slave was a capital good, hence not commoditized labor; but some skilled slaves hired out to others produced income for their masters and could keep a share for themselves. In his book Caribbean Transformations[18] and elsewhere, Mintz claimed that modernity originated in the Caribbean—Europe’s first factories were embodied in a plantation complex devoted to the cultivation of sugar cane and a few other agricultural commodities. The advent of this system certainly had profound effects on Caribbean “plantation society” (Mintz 1959a), but the commercialization of sugar’s products had lasting effects in Europe as well, from providing the wherewithal for the industrial revolution to transforming whole foodways and creating a revolution in European tastes and consumer behavior.[14][19] Mintz repeatedly insisted on the Caribbean region’s particularities[20][21] to contest pop notions of “globalization” and “diaspora,” that would make of the region a mere metaphor without acknowledging its historical distinctiveness.

Research

Caribbean anthropology

Mintz carried out his first fieldwork in the Caribbean in 1948 as part of Julian Steward’s application of anthropological methods to the study of a complex society. This fieldwork was eventually published as The People of Puerto Rico ?[22] Since then, Mintz has authored several books and nearly 300 scientific articles on varied themes, including slavery, labor, Caribbean peasantries, and the anthropology of food in the context of globalizing capitalism. In a field where insularity is common, and anthropologists usually chose one language area and one colonial power for study, Mintz has done fieldwork in three different Caribbean societies: Puerto Rico (1948-1949, 1953, 1956), Jamaica (1952, 1954), and Haiti (1958-1959, 1961), as well as later working in Iran (1966-1967) and Hong Kong (1996, 1999). Mintz has always taken a historical approach and used historical materials in studying Caribbean cultures.[7][9]

Peasantry

One of Mintz’s main contributions to Caribbean anthropology[23] has been his analysis of the origins and establishment of the peasantry. Mintz argued that Caribbean peasantries emerged alongside of and after industrialization, probably like nowhere else in the world.[17][24] Defining these as “reconstituted” because they began as something other than peasants, Mintz offered a tentative group typology. Such groups varied from the “squatters” who settled on the land in the early days after the Columbian conquest, through the “early yeomen,” European indentured plantation workers who finished the terms of their contracts; to the “proto-peasantry,” honing farming and marketing skills while still enslaved; and the “runaway peasantries” or maroons, who formed communities outside colonial authority, based on subsistence farming in mountainous or interior forest regions. For Mintz, these adaptations were a “mode of response” to the plantation system and a “mode of resistance” to superior power.[25] Acknowledging the difficulties in defining “peasantry,” Mintz pointed to the Caribbean experience, stressing internal peasant diversity in any given Caribbean society, as well as their relationships to landless wage-earning agricultural workers or “rural proletarians,” and how the experience of any individual might span or combine these categories.[26][27] Mintz was also interested in gender relations and the domestic economy, and especially in women’s roles in marketing.[28][29][30]

Sociocultural analysis

Anxious to illustrate complexity and diversity within the Caribbean, as well as the commonalities bridging cultural, linguistic, and political frontiers, Mintz argued in The Caribbean as a Socio-Cultural Area that

The very diverse origins of Caribbean populations; the complicated history of European cultural impositions; and the absence in most such societies of any firm continuity of the culture of the colonial power have resulted in a very heterogeneous cultural picture” when considering the region as a whole historically. “And yet the societies of the Caribbean — taking the word ‘society’ to refer here to forms of social structure and social organization — exhibit similarities that cannot possibly be attributed to mere coincidence” so that any “pan-Caribbean uniformities turn out to consist largely of parallels of economic and social structure and organization, the consequence of lengthy and rather rigid colonial rule,” such that many Caribbean societies “also share similar or historically related cultures.[31]

Mintz took a dialectical approach that highlighted contradictory forces. Thus, Caribbean slaves were individualized through the process of slavery and the relationship with modernity, “but not dehumanized by it.” Once free, they exhibited “quite sophisticated ideas of collective activity or cooperative unity. The push in Guyana to purchase plantations collectively; the use of cooperative work groups for house building, harvesting, and planting; the growth of credit institutions; and the links between kinship and coordinated work all suggest the powerful individualism that slavery helped to create did not wholly obviate group activity.”[32]

Slavery

Mintz has compared slavery and forced labor across islands, time and colonial structures, as in Jamaica and Puerto Rico (Mintz 1959b); and addressed the question of differing colonial systems engendering differing degrees of cruelty, exploitation, and racism. The view of some historians and political leaders in the Caribbean and Latin America was that the Iberian colonies, with their tradition of Catholicism and sense of aesthetics, meant a more humane slavery; while north European colonies, with their individualizing Protestant religions, found it easier to exploit the slaves and to draw hard and fast social categories. But Mintz argued that the treatment of slaves had to do instead with the integration of the colony into the world economic system, the degree of control of the metropolis over the colony, and the intensity of exploitation of labor and land.'[33] In collaboration with anthropologist Richard Price, Mintz considered the question of creolization (a sort of blending of multiple cultural traditions to create a new one) in African American culture in the book The Birth of African-American Culture: An Anthropological Approach (Mintz and Price 1992, first published in 1976 and first delivered as a conference paper in1973). There, the authors qualify anthropologist Melville J. Herskovits’s view that Afro-American culture was mainly African cultural survivals. But they also oppose those who claimed African culture was stripped from the slaves through enslavement, such that nothing “African” remains in Afro-American cultures today. Combining Herskovits’s cultural anthropological approach and the structuralism of anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss, Mintz and Price argued that Afro-Americana is characterized by deep-level “grammatical principles” of various African cultures, and that these principles extend to motor behaviors, kinship practices, gender relations, and religious cosmologies. This has been an influential model in the ongoing anthropology of the African diaspora.[23]

Recent work

More recent work by Mintz has focused on the history and meaning of food (e.g., Mintz 1985b, 1996b; Mintz and Du Bois 2002), including ongoing work on the consumption of soy foods.[34]

References

- General

- Baca, George. 2016 "Sidney W. Mintz: from the Mundial Upheaval Society to a dialectical anthropology," Dialectical Anthropology, 40: 1-11.

- Brandel, Andrew and Sidney W. Mintz. 2013. "Preface: Levi-Strauss and the True Sciences." Special Issue of "Hau: A Journal of Ethnographic Theory" 3(1).

- Duncan, Ronald J., ed. 1978 "Antropología Social en Puerto Rico/Social Anthropology in Puerto Rico." Special Section of Revista/Review Interamericana 8(1).

- Ghani, Ashraf, 1998 "Routes to the Caribbean: An Interview with Sidney W. Mintz". Plantation Society in the Americas 5(1):103-134.

- Lauria-Perriceli, Antonio, 1989 A Study in Historical and Critical Anthropology: The Making of The People of Puerto Rico. Unpublished Ph.D. dissertation, New School for Social Research.

- Mintz, Sidney W. 1959a "The Plantation as a Socio-Cultural Type". In Plantation Systems of the New World. Vera Rubin, ed. Pp. 42–53. Washington, DC: Pan-American Union.

- Mintz, Sydney W. 1959b "Labor and Sugar in Puerto Rico and in Jamaica, 1800-1850". In Comparative Studies in Society and History 1(3): 273-281.

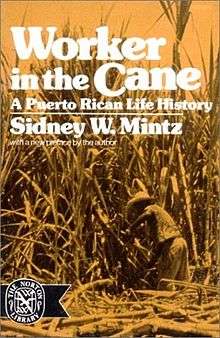

- Mintz, Sidney W. 1960 Worker in the Cane: A Puerto Rican Life History. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Mintz, Sidney W. 1966 "The Caribbean as a Socio-Cultural Area". In Cahiers d’Histoire Mondiale 9: 912-937.

- Mintz, Sidney W. 1971 "Men, Women and Trade". In Comparative Studies in Society and History 13(3): 247-269.

- Mintz, Sidney W. 1973 "A Note on the Definition of Peasantries". In Journal of Peasant Studies 1(1): 91-106.

- Mintz, Sidney W. 1974a Caribbean Transformations. Chicago: Aldine.

- Mintz, Sidney W. 1974b "The Rural Proletariat and the Problem of Rural Proletarian Consciousness". In Journal of Peasant Studies 1(3): 291-325.

- Mintz, Sidney W. 1977 "The So-Called World-System: Local Initiative and Local Response". In Dialectical Anthropology 2(2):253-270.

- Mintz, Sidney W. 1978 "Was the Plantation Slave a Proletarian?" In Review 2(1):81-98.

- Mintz, Sidney W. 1981a "Ruth Benedict". In Totems and Teachers: Perspectives on the History of Anthropology. Sydel Silverman, ed. Pp. 141–168. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Mintz, Sidney W. 1981b "Economic Role and Cultural Tradition". In The Black Woman Cross-Culturally. Filomina Chioma Steady, ed. Pp. 513–534. Cambridge, MA: Schenkman.

- Mintz, Sidney W. ed., 1985a History, Evolution, and the Concept of Culture: Selected Papers by Alexander Lesser. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Mintz, Sidney Wilfred (1985b). Sweetness and Power: The Place of Sugar in Modern History. New York: Viking. ISBN 0-670-68702-2.

- Mintz, Sidney W. 1985c "From Plantations to Peasantries in the Caribbean". In Caribbean Contours. Sidney W. Mintz and Sally Price, eds. Pp. 127–153. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Mintz, Sidney W. 1989 "The Sensation of Moving While Standing Still". In American Ethnologist 17(4):786-796.

- Mintz, Sidney W. 1992 "Panglosses and Pollyannas; or Whose Reality Are We Talking About?" In The Meaning of Freedom: Economics, Politics, and Culture after Slavery. Frank McGlynn and Seymour Drescher, eds. Pp. 245–256. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press.

- Mintz, Sidney W. 1996a Tasting Food, Tasting Freedom: Excursions into Eating, Culture, and the Past. Boston: Beacon Press.

- Mintz, Sidney W. 1996b "Enduring Substances, Trying Theories: The Caribbean Region as OikoumenL". In Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute (N.S.) 2(2):289-311.

- Mintz, Sidney W. 1998 "The Localization of Anthropological Practice: From Area Studies to Transnationalism". In Critique of Anthropology 18(2):117-133.

- Mintz, Sidney W. 2002 "People of Puerto Rico Half a Century Later: One Author’s Recollections". In Journal of Latin American Anthropology 6(2):74-83.

- Mintz, Sidney W. and Christine M. Du Bois, 2002, "The Anthropology of Food and Eating". In Annual Review of Anthropology 31: 99-119.

- Mintz, Sidney W. and Chee Beng Tan 2001 "Bean-Curd Consumption in Hong Kong". Ethnology 40(2): 113-128.

- Mintz, Sidney W. and Richard Price 1992 The Birth of African-American Culture: An Anthropological Approach. Boston: Beacon Press.

- Scott, David 2004 "Modernity that Predated the Modern: Sidney Mintz’s Caribbean". In History Workshop Journal 58:191-210.

- Steward, Julian H. Steward, Robert A. Manners, Eric R. Wolf, Elena Padilla Seda, Sidney W. Mintz, and Raymond L. Scheele 1956 The People of Puerto Rico: A Study in Social Anthropology. Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

- Yelvington, Kevin A. 1996 "Caribbean". In Encyclopedia of Social and Cultural Anthropology. Alan Barnard and Jonathan Spencer, eds. Pp. 86–90. London: Routledge.

- Yelvington, Kevin A. 2001 "The Anthropology of Afro-Latin America and the Caribbean: Diasporic Dimensions". Annual Review of Anthropology 30: 227-260.

- Specific

- ↑ https://www.nytimes.com/2015/12/30/us/sidney-mintz-father-of-food-anthropology-dies-at-93.html

- 1 2 3 Kuever, Erika (May 2006). "Sidney Mintz". Sociocultural Theory in Anthropology. Indiana University. Retrieved 28 February 2015.

- ↑ Bentley, Amy (2012). "Sustenance, Abundance, and The Place of Food In United States History". In Claflin, Kyri W.; Scholliers, Peter. Writing Food History: A Global Perspective. Blomsbury. ISBN 9781847888082.

- ↑ "Mintz, Sidney Wilfred 74-75 Soc, Anthropology, History Born 1922 Dover, NJ." Woolf, Harry, ed. (1980), A Community of Scholars: The Institute for Advanced Study Faculty and Members 1930-1980 (PDF), Princeton, New Jersey: Institute for Advanced Study, p. 293, archived (PDF) from the original on November 24, 2011

- 1 2 3 Yelvington, Kevin A.; Bentley, Amy (2013). "Mintz, Sidney" (PDF). In McGee, Jon; Warms, Richard L. Theory in Social and Cultural Anthropology: An Encyclopedia. Los Angeles: Sage Reference. pp. 548–552. ISBN 9781412999632. Retrieved 28 February 2015.

- ↑ Duncan, Ronald J. (1978). "Antropología Social en Puerto Rico/Social Anthropology in Puerto Rico". Revista/Review Interamericana. 8 (1).

- 1 2 Ghani, Ashram (1998). "Routes to the Caribbean: An Interview with Sidney W. Mintz". Plantation Society in the Americas. 5 (1): 103–134.

- ↑ Lauria-Perriceli, Antonio (1989). A Study in Historical and Critical Anthropology: The Making of The People of Puerto Rico. New York: Unpublished PhD New School of Social Research.

- 1 2 Scott, David (2004). "Modernity that Predated the Modern: Sidney Mintz’s Caribbean". History Workshop Journal. 58: 191–210. doi:10.1093/hwj/58.1.191.

- ↑ Mintz, Sidney W. (1989). "The Sensation of Moving While Standing Still". American Ethnologist. 17 (4): 786–796. doi:10.1525/ae.1989.16.4.02a00100.

- ↑ MintzSidney, Sidney W. (2002). "People of Puerto Rico Half a Century Later: One Author’s Recollections". Journal of Latin American Anthropology'. 6 (2): 74–83.

- ↑ http://www.jhu.edu/registrar/catalog.pdf

- ↑ https://www.nytimes.com/2015/12/30/us/sidney-mintz-father-of-food-anthropology-dies-at-93.html?_r=0

- 1 2 Mintz, Sidney W. (1985). History, Evolution, and the Concept of Culture: Selected Papers by Alexander Lesser. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- ↑ Mintz, Sidney W. (1977). "The So-Called World-System: Local Initiative and Local Response". Dialectical Anthropology. 2 (2): 254–255. doi:10.1007/bf00249489.

- ↑ Mintz, Sidney (1960). Worker in the Cane: A Puerto Rican Life History. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- 1 2 Mintz, Sidney W. (1978). "Was the Plantation Slave a Proletarian?". Review. 2 (1): 81–98.

- ↑ Mintz, Sidney W. (1974). Caribbean Transformations. Chicago: Aldine.

- ↑ Mintz, Sidney W. (1996). Tasting Food, Tasting Freedom: Excursions into Eating, Culture, and the Past. New York: Basic Books.

- ↑ Mintz, Sidney W. (1996). "Enduring Substances, Trying Theories: The Caribbean Region as OikoumenL". Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute. N.s. 2 (2): 289–311.

- ↑ Mintz, Sidney W. (1998). "The Localization of Anthropological Practice: From Area Studies to Transnationalism". Critique of Anthropology. 18 (2): 117–133. doi:10.1177/0308275x9801800201.

- ↑ Steward, Julian; et al. The People of Puerto Rico: A Study in Social Anthropology'. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press.

- 1 2 Yelvington, Kevin A. (2001). "The Anthropology of Afro-Latin America and the Caribbean: Diasporic Dimensions". Annual Review of Anthropology. 30: 227–260. doi:10.1146/annurev.anthro.30.1.227.

- ↑ Mintz, Sidney (1985). Caribbean Contours. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 127–153.

- ↑ Mintz, Sidney W. (1974). Caribbean Transformations. Chicago: Aldine. pp. 131–156.

- ↑ Mintz, Sindey W. (1973). "A Note on the Definition of Peasantries". Journal of Peasant Studies. 1 (1): 96–106. doi:10.1080/03066157308437874.

- ↑ Mintz, Sidney W. (1974b). "The Rural Proletariat and the Problem of Rural Proletarian Consciousness". Journal of Peasant Studies. 1 (3): 291–325. doi:10.1080/03066157408437893.

- ↑ Mintz, Sidney W. (1971). "Men, Women and Trade". Comparative Studies in Society and History. 13 (3): 247–269. doi:10.1017/s0010417500006277.

- ↑ Mintz, Sidney (1981). "Ruth Benedict". In Silverman, Sydel. Totems and Teachers: Perspectives on the History of Anthropology. New York: Columbia University Press. pp. 103–124. ISBN 978-0-231-05086-9.

- ↑ Mintz, Sidney W. (1981). "Economic Role and Cultural Tradition". In Steady, Filomina Chioma. The Black Woman Cross-culturally. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Schenkman. pp. 515–534. ISBN 978-0-87073-345-1.

- ↑ Mintz, Sidney W. (1966). "The Caribbean as a Socio-Cultural Area". Cahiers d’Histoire Mondiale. 9: 912–37.

- ↑ Mintz, Sidney W. (1992). "Panglosses and Pollyannas; or Whose Reality Are We Talking About?". In McGlynn, Frank; Drescher, Seymour. The Meaning of Freedom: Economics, Politics, and Culture after Slavery. Pitt Latin American series. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press. pp. 252–253. ISBN 978-0-8229-3695-4.

- ↑ Mintz, Sidney W. (1974). Caribbean Transformations. Chicago: Aldine. pp. 59–81.

- ↑ Mintz, Sidney W.; Tan, Chee Beng (2001). "Bean-Curd Consumption in Hong Kong". Ethnology. 40 (2): 113–128. JSTOR 3773926. doi:10.2307/3773926.

External links

- sidneymintz.net - Official website

- Sidney Mintz at the Johns Hopkins University Department of Anthropology

- Film of Sidney Mintz speaking on 'creolization' at LACNET, University of St Andrews.

- Sidney Mintz in conversation with Sonia Ryang 7th April 2007 (film)

- The New York Times obituary