Western bluebird

| Western bluebird | |

|---|---|

| |

| Adult male | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Passeriformes |

| Family: | Turdidae |

| Genus: | Sialia |

| Species: | S. mexicana |

| Binomial name | |

| Sialia mexicana Swainson, 1832 | |

| |

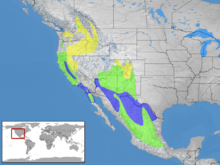

| Range of S. mexicana Breeding range Year-round range Wintering range | |

The western bluebird (Sialia mexicana) is a small thrush, about 15 to 18 cm (5.9 to 7.1 in) in length. Adult males are bright blue on top and on the throat with an orange breast and sides, a brownish patch on back, and a gray belly and undertail coverts. Adult females have a duller blue body, wings, and tail than the male, a gray throat, a dull orange breast, and a gray belly and undertail coverts. Immature western bluebirds have duller colors than the adults, they also have spots on their chest and back. These color patterns help play a part in the mating ritual, when males compete for breeding rights to females.[2]

They are sometimes confused with other bluebirds, but they can be distinguished without difficulty. The western bluebird has a blue (male) or gray (female) throat, the eastern bluebird has an orange throat, and the mountain bluebird lacks orange color anywhere on its body. It has a stocky build, and a thin straight beak with a fairly short tail.

Its posture consists of perching upright on wire fences and high perches. The western bluebird pounces on the ground when looking for food, such as worms and berries. It also flies to catch aerial prey, like insects, when available. The western bluebird consumes water from nearby streams and commonly used bird baths.[3]

Nesting

Nesting habitat

The western bluebird has been chased out of its natural habitat due to the cutting down of trees; however the western bluebird has adapted to coniferous forests, farmlands, semi-open terrain, and desert to survive. The year-round range includes California, the southern Rocky Mountains, Arizona, and New Mexico in the United States, and as far south as the states of Oaxaca and Veracruz in Mexico. The summer breeding range extends as far north as the Pacific Northwest, British Columbia, and Montana. Northern birds can migrate to the southern parts of the range; southern birds are often permanent residents.

They nest in cavities or in nest boxes, competing with tree swallows, house sparrows, and European starlings for natural nesting locations. Because of the high level of competition, house sparrows often attack western bluebirds for their nests. The attacks are made both in groups or alone. Attacks by starlings can be reduced if the nesting box opening is kept to 1.5 in (38 mm) diameter to avoid takeover. Nest boxes come into effect when the species is limited and dying out due to the following predators: cats, raccoons, possums, and select birds of prey such as the Cooper’s hawk. Ants, bees, earwigs, and wasps can crawl into the nesting boxes and damage the newborns.[4] Western bluebirds are among the birds that nest in [cavities], or holes in trees, or nest boxes. Their [beak]s are too weak and small to dig out their own holes, so they rely on [woodpecker]s to make their nest sites for them.[5]

Nest type and habitat comparison

_eggs.jpg)

In restored forests, western bluebirds have a higher probability of successfully fledging young than in untreated forests, but they are at greater risk of parasitic infestations. The effects on post-fledging survival are unknown.[6] They have been found to enjoy more success with nest boxes than in natural cavities. They started egg-laying earlier, had higher nesting success and lower predation rates, and fledged more young in boxes than in cavities, but they did not have larger clutches of eggs.

The eggs are commonly two to eight per clutch, with average size 20.8 mm × 16.2 mm (0.82 in × 0.64 in). Eggs are oval in shape with a smooth and glossy shell. They are pale blue to bluish-white and sometimes white in color. Nestlings remain in a nest about 19 to 22 days before fledging.

Rearing of young

In a good year, the parents can rear two broods, with four to six eggs per clutch. According to genetic studies, 45% of western bluebirds' nests carried young that were not offspring of the male partner. In addition, they help their parents raise a new brood after their own nest fails.

These birds wait on a perch and fly down to catch insects, sometimes catching them in midair. They mainly eat insects and berries. During the breeding season, bluebirds are very helpful with pest control in the territory surrounding the nest.

Calls and songs

Their calling consists of the mating songs which sound like “cheer,” “chur-chur,” and “chup.” This helps male western bluebirds find the females easily in condensed f “chweer” or “che-cheek,” to tell [competing] males that the [territory] belongs to them.[7]

Similar species

- Eastern bluebird (Sialia sialis)

- Mountain bluebird (Sialia currucoides)

References

.jpg)

- ↑ BirdLife International (2012). "Sialia mexicana". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2013.2. International Union for Conservation of Nature. Retrieved 26 November 2013.

- ↑ Powell, Hugh; Barry, Jessie; Haber, Scott; Parke-Houben, Annetta (2011). "Western Bluebird" (Web Article). The Cornell Lab of Ornithology. Retrieved October 5, 2011.

- ↑ Powell, Hugh; Barry, Jessie; Haber, Scott; Parke-Houben, Annetta (2011). "Western Bluebird" (Web Article). The Cornell Lab of Ornithology. Retrieved October 10, 2014.

- ↑ Powell, Hugh; Barry, Jessie; Haber, Scott; Parke-Houben, Annetta (2011). "Western Bluebird" (Web Article). The Cornell Lab of Ornithology. Retrieved October 10, 2014.

- ↑ Powell, Hugh; Barry, Jessie; Haber, Scott; Parke-Houben, Annetta (2011). "Western Bluebird" (Web Article). The Cornell Lab of Ornithology. Retrieved October 10, 2014.

- ↑ Germaine, H., Germaine, S. (2002) Restoration Ecology; Restoration Ecology 10(2), 362–367

- ↑ Powell, Hugh; Barry, Jessie; Haber, Scott; Parke-Houben, Annetta (2011). "Western Bluebird" (Web Article). The Cornell Lab of Ornithology. Retrieved October 10, 2014.

- Sibley, D. A. 2003. The Sibley Field Guide to Birds of North America. Chanticleer Press, New York.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sialia mexicana. |

| Wikispecies has information related to: Sialia mexicana |

- Western Bluebird Species Account – Cornell Lab of Ornithology

- Western Bluebird Species Information from Bluebird Information and Awareness

- "Western bluebird media". Internet Bird Collection.

- Western Bluebird - Sialia mexicana - USGS Patuxent Bird Identification InfoCenter

- Western Bluebird slow motion hovering video on YouTube

- Western bluebird photo gallery at VIREO (Drexel University)