The Shadow

| The Shadow | |

|---|---|

|

Art by John Cassaday | |

| Publication information | |

| Publisher |

Street & Smith Condé Nast |

| First appearance |

Detective Story Hour (July 31, 1930)[1] (radio) "The Living Shadow" (April 1, 1931)[1] (print) |

| Created by | Walter B. Gibson |

| In-story information | |

| Alter ego |

Kent Allard (print) Lamont Cranston (radio, film and television) |

| Notable aliases |

Lamont Cranston (print) Henry Arnaud (print) Isaac Twambley (print) Fritz the Janitor (print) |

| Abilities |

In print, radio, and film: In radio and film only:

|

The Shadow is the name of a collection of serialized dramas, originally in 1930s pulp novels, and then in a wide variety of media, and it is also used to refer to the character featured in The Shadow media.[2] One of the most famous adventure heroes of the 20th century United States, the Shadow has been featured on the radio, in a long-running pulp magazine series, in comic books, comic strips, television, serials, video games, and at least five films. The radio drama included episodes voiced by Orson Welles.

Originally simply a mysterious radio narrator who hosted a program designed to promote magazine sales for Street and Smith Publications, The Shadow was developed into a distinctive literary character, later to become a pop culture icon, by writer Walter B. Gibson in 1931. The character has been cited as a major influence on the subsequent evolution of comic book superheroes, particularly Batman.[3]

The Shadow debuted on July 31, 1930, as the mysterious narrator of the Street and Smith radio program Detective Story Hour, which was developed in an effort to boost sales of Detective Story Magazine.[4] When listeners of the program began asking at newsstands for copies of "That Shadow detective magazine," Street & Smith decided to create a magazine based around The Shadow and hired Gibson to create a character concept to fit the name and voice and write a story featuring him. The first issue of The Shadow Magazine went on sale on April 1, 1931, a pulp series.

On September 26, 1937, The Shadow radio drama, a new radio series based on the character as created by Gibson for the pulp magazine, premiered with the story "The Death House Rescue," in which The Shadow was characterized as having "the power to cloud men's minds so they cannot see him." As in the magazine stories, The Shadow was not given the literal ability to become invisible.

The introduction from The Shadow radio program "Who knows what evil lurks in the hearts of men? The Shadow knows!", spoken by actor Frank Readick Jr, has earned a place in the American idiom. These words were accompanied by an ominous laugh and a musical theme, Camille Saint-Saëns' Le Rouet d'Omphale ("Omphale's Spinning Wheel", composed in 1872). At the end of each episode The Shadow reminded listeners that, "The weed of crime bears bitter fruit. Crime does not pay...The Shadow knows!" (Some early episodes, however, used the alternate statement, "As you sow evil, so shall you reap evil. Crime does not pay...The Shadow knows!")

Publication history

Origin of the character's name

In order to boost the sales of their Detective Story Magazine, Street and Smith Publications hired David Chrisman of the Ruthrauff & Ryan advertising agency and writer-director William Sweets to adapt the magazine's stories into a radio series. Chrisman and Sweets felt the upcoming series should be narrated by a mysterious storyteller with a sinister voice, and began searching for a suitable name. One of their scriptwriters, Harry Engman Charlot, suggested various possibilities, such as "The Inspector" or "The Sleuth."[5] Charlot then proposed the ideal name for the phantom announcer: "... The Shadow."[5]

Thus, beginning on July 31, 1930,[1][6] "The Shadow" was the name given to the mysterious narrator of the Detective Story Hour. The narrator was initially voiced by James LaCurto,[6] who was replaced after four months by prolific character actor Frank Readick Jnr. The episodes were drawn from the Detective Story Magazine issued by Street and Smith, "the nation's oldest and largest publisher of pulp magazines."[6] Although the latter company had hoped the radio broadcasts would boost the declining sales of Detective Story Magazine, the result was quite different. Listeners found the sinister announcer much more compelling than the unrelated stories. They soon began asking newsdealers for copies of "that Shadow detective magazine," even though it did not exist.[6]

Creation as a distinctive literary character

Recognizing the demand and responding promptly, circulation manager Henry William Ralston of Street & Smith commissioned Walter B. Gibson to begin writing stories about "The Shadow." Using the pen name of Maxwell Grant and claiming the stories were "from The Shadow's private annals as told to" him, Gibson wrote 282 out of 325 tales over the next 20 years: a novel-length story twice a month (1st and 15th). The first story produced was The Living Shadow, published April 1, 1931.[6]

Gibson's characterization of The Shadow laid the foundations for the archetype of the superhero, including stylized imagery and title, sidekicks, supervillains, and a secret identity. Clad in black, The Shadow operated mainly after dark as a vigilante in the name of justice, and terrifying criminals into vulnerability. Gibson himself claimed the literary inspirations upon which he had drawn were Bram Stoker's Dracula and Edward Bulwer-Lytton's "The House and the Brain."[5] Another possible inspiration for The Shadow is the French character Judex; the first episode of the original Judex film serial was released in the United States as The Mysterious Shadow, and Judex's costume is rather similar to The Shadow's. French comics historian Xavier Fournier notes other similarities with another silent serial, The Shielding Shadow, whose protagonist had a power of invisibility, and considers The Shadow to be a mix between the two characters. In the 1940s, some Shadow comic strips were translated in France as adventures of Judex.[7]

Because of the great effort involved in writing two full-length novels every month, several guest writers were hired to write occasional installments in order to lighten Gibson's workload. These guest writers included Lester Dent, who also wrote the Doc Savage stories, and Theodore Tinsley. In the late 1940s, mystery novelist Bruce Elliott (also a magician) would temporarily replace Gibson as the primary author of the pulp series.[8] Richard Wormser, a reader for Street & Smith, wrote two Shadow stories.[9]

The Shadow Magazine ceased publication with the Summer 1949 issue, but Walter B. Gibson wrote three new "official" stories between 1963 and 1980. The first of these began a new series of nine updated Shadow novels from Belmont Books, starting with Return of The Shadow under his own by-line. But the remaining eight--The Shadow Strikes, Beware Shadow, Cry Shadow, The Shadow's Revenge, Mark of The Shadow, Shadow Go Mad, Night of The Shadow, and The Shadow, Destination: Moon--were written, not by Gibson, but instead by Dennis Lynds under the "Maxwell Grant" byline. In these last eight novels, The Shadow was given psychic powers, including the radio character's ability "to cloud men's minds" so that he effectively became invisible, and was more of a spymaster than crime fighter.

The Shadow returned in 2015 in the authorized novel The Sinister Shadow, which was an entry in the Wild Adventures of Doc Savage series from Altus Press. The novel was written by Will Murray, who used unpublished material originally written in 1932 by Doc Savage originator Lester Dent and published under the pen name of Kenneth Robeson. Set in 1933, the story details the conflict between the two pulp magazine icons.

A sequel appeared in 2016. Empire of Doom takes place several years later in 1940. Here, The Shadow's old enemy, Shiwan Khan, attacks his hated adversary, and Doc Savage joins forces with The Shadow to vanquish him in a Doc Savage novel written by Will Murray from a concept by Lester Dent.

Publications

See List of The Shadow stories

Character development

The character and look of The Shadow gradually evolved over his lengthy fictional existence:

As depicted in the pulps, The Shadow wore a wide-brimmed black hat and a black, crimson-lined cloak with an upturned collar over a standard black business suit. In the 1940s comic books, the later comic book series, and the 1994 film starring Alec Baldwin, he wore either the black hat or a wide-brimmed, black fedora and a crimson scarf just below his nose and across his mouth and chin. Both the cloak and scarf covered either a black double-breasted trench coat or a regular black suit. As seen in some of the later comics series, The Shadow would also wear his hat and scarf with either a black Inverness coat or Inverness cape.

In the radio drama, which debuted in 1937, The Shadow was an invisible avenger who had learned, while "traveling through East Asia," "the mysterious power to cloud men's minds, so they could not see him." This feature of the character was born out of necessity: time constraints of 1930s radio made it difficult to explain to listeners where The Shadow was hiding and how he was remaining concealed. Thus, the character was given the power to escape human sight. Voice effects were added to suggest The Shadow's seeming omnipresence. To explain this power, The Shadow was described as a master of hypnotism, as explicitly stated in several radio episodes.

Background

In print, The Shadow's real name is Kent Allard, and he was a famed aviator who fought for the French during World War I. He became known by the alias the Black Eagle, according to The Shadow's Shadow (1933), although later stories revised this alias as the Dark Eagle, beginning with The Shadow Unmasks (1937). After the war, Allard finds a new challenge in waging war on criminals. Allard falsifies his death in the South American jungles, then returns to the United States. Arriving in New York City, he adopts numerous identities to conceal his existence.

One of the identities Allard assumes--indeed, the best known--is that of Lamont Cranston, a "wealthy young man-about-town." In the pulps, Cranston is a separate character; Allard frequently disguises himself as Cranston and adopts his identity (The Shadow Laughs, 1931). While Cranston travels the world, Allard assumes his identity in New York. In their first meeting, Allard, as The Shadow, threatens Cranston, saying he has arranged to switch signatures on various documents and other means that will allow him to take over the Lamont Cranston identity entirely unless Cranston agrees to allow Allard to impersonate him when he is abroad. Although alarmed at first, Cranston is amused by the irony of the situation and agrees. The two men sometimes meet in order to impersonate each other (Crime over Miami, 1940). The disguise works well because Allard and Cranston resemble each other (Dictator of Crime, 1941).

His other disguises include businessman Henry Arnaud, who first appeared in The Black Master (March 1, 1932), which revealed that like Cranston, there is a real Henry Arnaud; elderly Isaac Twambley, who first appeared in No Time For Murder; and Fritz, who first appeared in The Living Shadow (April 1931); in this last disguise, he pretends to be a doddering old slow-witted, uncommunicative janitor who works at Police Headquarters in order to listen in on conversations.

For the first half of The Shadow's tenure in the pulps, his past and identity are ambiguous, supposedly an intentional decision on Gibson's part. In The Living Shadow, a thug claims to have seen the Shadow's face, and thought he saw "a piece of white that looked like a bandage." In The Black Master and The Shadow's Shadow, the villains both see The Shadow's true face and remark that The Shadow is a man of many faces with no face of his own. It was not until the August 1937 issue, The Shadow Unmasks, that The Shadow's real name is revealed.

In the radio drama, the Allard secret identity was dropped for simplicity's sake. On the radio, The Shadow was only Lamont Cranston; he had no other aliases or disguises.

Supporting characters

The Shadow has a network of agents who assist him in his war on crime. These include:

- Harry Vincent, an operative whose life he saved when Vincent tried to commit suicide in the first Shadow story.

- Moses "Moe" Shrevnitz, aka "Shrevvy," a cab driver who doubles as his chauffeur. (Peter Boyle performed the role in the 1994 film.)

- Margo Lane, a socialite created for the radio drama and later introduced into the pulps. (Penelope Ann Miller performed the role in the 1994 film, in which Margo was granted the power of telepathy, and hence the ability to pierce The Shadow's hypnotic mental-clouding abilities.)

- Clyde Burke, a newspaper reporter who also is paid to collect news clippings for The Shadow.

- Burbank, a radio operator who maintains contact between The Shadow and his agents. (He was portrayed by Andre Gregory in the 1994 film.)

- Clifford "Cliff" Marsland. He first appeared in the ninth novel (Mobsmen on the Spot). He is a man with a checkered past (known to The Shadow) who changed his name to Clifford Marsland. He spent years in Sing Sing (jail) for a crime he did not commit and is wrongly believed to have murdered one or more people by the Underworld. He infiltrates gangs using his crooked reputation. (The Green Hornet is often described as having a similar modus operandi to that of Marsland.)

- Dr. Rupert Sayre, The Shadow's personal physician.

- Jericho Druke, a giant, immensely strong black man.

- Slade Farrow, who works with The Shadow to rehabilitate criminals.

- Miles Crofton, who sometimes pilots The Shadow's autogyro.

- Claude Fellows, the only agent of The Shadow ever to be killed, in Gangdom's Doom (1931).

- Rutledge Mann, a stockbroker who collects information; he took over from Claude Fellows. First appeared in Double Z (June 1, 1932). Known to Cranston, his business had failed and he was heavily in debt and ready to commit suicide before The Shadow recruited him.

- Hawkeye, a reformed underworld snoop who trails gangsters and other criminals.

- Myra Reldon, a female operative who uses the alias of Ming Dwan when in Chinatown.

- Dr. Roy Tam, The Shadow's contact man in New York's Chinatown. (Sab Shimono portrayed him in the 1994 film, in which he provided valuable information to Lamont Cranston, believing the latter to be an agent of The Shadow.)

Though initially wanted by the police, The Shadow also works with and through them, notably gleaning information from his many chats with Police Commissioners Ralph Weston and Wainwright Barth while at the Cobalt Club; the latter is also Cranston's uncle. (Jonathan Winters portrayed him in the 1994 film.) Weston believes that Cranston is merely a rich playboy who dabbles in detective work. Another police contact is Detective (later Inspector) Joseph Cardona, a key character in many Shadow novels.

In contrast to the pulps, The Shadow radio drama limited the cast of major characters to The Shadow, Commissioner Weston, and Margo Lane, the last of whom was created specifically for the radio series, as it was believed the abundance of agents would make it difficult to distinguish between characters.[10] Harry Vincent appeared as an agent of The Shadow in the first episode, "The Death House Rescue." Clyde Burke and Moe Shrevnitz (identified only as "Shrevvy") made occasional appearances, but not as agents of The Shadow. Lt. Cardona was a minor character in several episodes. Shrevvy was merely an acquaintance of Cranston and Lane, and occasionally Cranston's chauffeur.

Enemies

The Shadow also faces a wide variety of enemies, ranging from kingpins and mad scientists to international spies and "supervillains," many of whom were predecessors to the rogues galleries of comic super-heroes. Among The Shadow's recurring foes are Shiwan Khan, seen in The Golden Master, Shiwan Khan Returns, Invincible Shiwan Khan, and Masters of Death (in the 1994 film, John Lone portrayed the character); Dr. Rodil Moquino, the Voodoo Master (The Voodoo Master, The City of Doom, and Voodoo Trail); Bernard Stark, the Prince of Evil (The Prince of Evil, The Murder Genius, The Man Who Died Twice, and The Devil's Paymaster, all written by Theodore Tinsley); and The Wasp (The Wasp and The Wasp Returns). The only recurring criminal organization he fought was The Hand (The Hand, Murder for Sale, Chicago Crime, Crime Rides the Sea, and Real of Doom), where he defeated one Finger of the organization in each book. In addition, the supervillain King Kauger from the Shadow story Wizard of Crime is also the unseen mastermind behind the events of Intimidation, Inc.

The series also featured a myriad of one-shot villains, including The Red Envoy, The Death Giver, Gray Fist, The Black Dragon, Silver Skull, The Red Blot, The Black Falcon, The Cobra, Gaspard Zemba, The Black Master, Five-Face, The Gray Ghost, and Dr. Z.

The Shadow also battles collectives of criminals, such as The Silent Seven (his targets in an adventure all their own), The Hand, The Salamanders, and The Hydra.

Radio program

In early 1930, Street & Smith hired David Chrisman and Bill Sweets to adapt the Detective Story Magazine to radio format. Chrisman and Sweets felt the program should be introduced by a mysterious storyteller. A young scriptwriter, Harry Charlot, suggested the name of "The Shadow."[5] Thus, "The Shadow" premiered over CBS airwaves on July 31, 1930,[1] as the host of the Detective Story Hour,[6] narrating "tales of mystery and suspense from the pages of the premier detective fiction magazine."[6] The bulk of the radio show was written primarily by Sidney Slon. The narrator was first voiced by James La Curto,[6] but became a national sensation when radio veteran Frank Readick, Jr. assumed the role and gave it "a hauntingly sibilant quality that thrilled radio listeners."[6]

Early years

Following a brief tenure as narrator of Street & Smith's Detective Story Hour, "The Shadow" character was used to host segments of The Blue Coal Radio Revue, playing on Sundays at 5:30 p.m. Eastern Standard Time. This marked the beginning of a long association between the radio persona and sponsor Blue Coal.

While functioning as a narrator of The Blue Coal Radio Revue, the character was recycled by Street & Smith in October 1931, for their newly created Love Story Hour. Contrary to dozens of encyclopedias, published reference guides, and even Walter Gibson himself, The Shadow never served as narrator of Love Story Hour. He appeared only in advertisements for The Shadow Magazine at the end of each episode.[11]

In October 1932, the radio persona temporarily moved to NBC. Frank Readick again played the role of the sinister-voiced host on Mondays and Wednesdays, both at 6:30 p.m., with La Curto taking occasional turns as the title character.

Readick returned as The Shadow to host a final CBS mystery anthology that fall. The series disappeared from CBS airwaves on March 27, 1935, due to Street & Smith's insistence that the radio storyteller be completely replaced by the master crime-fighter described in Walter B. Gibson's ongoing pulps.

Radio drama

Street & Smith entered into a new broadcasting agreement with Blue Coal in 1937, and that summer Gibson teamed with scriptwriter Edward Hale Bierstadt to develop the new series. The Shadow returned to network airwaves on September 26, 1937,[12] over the new Mutual Broadcasting System. Thus began the "official" radio drama, with 22-year-old Orson Welles starring as Lamont Cranston, a "wealthy young man about town." Once The Shadow joined Mutual as a half-hour series on Sunday evenings, the program did not leave the air until December 26, 1954.

Welles did not speak the signature line, "Who knows what evil lurks in the hearts of men?" Instead, Readick did, using a water glass next to his mouth for the echo effect. The famous catch phrase was accompanied by the strains of an excerpt from Opus 31 of the Camille Saint-Saëns classical composition, Le Rouet d'Omphale.

After Welles departed the show in 1938, Bill Johnstone was chosen to replace him and voiced the character for five seasons. Following Johnstone's departure, The Shadow was portrayed by such actors as Bret Morrison (the longest tenure, with 10 years in two separate runs), John Archer, and Steve Courtleigh. (The actors were rarely credited.)

The Shadow also inspired another radio hit, The Whistler, with a similarly mysterious narrator.

Margo Lane

The radio drama also introduced female characters into The Shadow's realm, most notably Margo Lane (played by Agnes Moorehead, among others) as Cranston's love interest, crime-solving partner and the only person who knows his identity as The Shadow.[13] Four years later, the character was introduced into the pulp novels. Her sudden, unexplained appearance in the pulps annoyed readers and generated a flurry of hate mail printed in The Shadow Magazine's letters page.[13]

Lane was described as Cranston's "friend and companion" in later episodes, although the exact nature of their relationship was unclear. In the early scripts of the radio drama the character's name was spelled "Margot." The name itself was originally inspired by Margot Stevenson,[13] the Broadway ingénue who would later be chosen to voice Lane opposite Welles' The Shadow during "the 1938 Goodrich summer season of the radio drama."[14] In the 1994 film in which Penelope Ann Miller acted out the character, she is described as being telepathic and hence aware of, but specifically immune to, The Shadow's abilities.

Radio drama LPs

In 1968 Metro Record's "Leo the Lion" label released an LP titled The Official Adventures of The Shadow (CH-1048) with two original fifteen-minute radio-style productions written by John Fleming: "The Computer Calculates, but The Shadow Knows" and "Air Freight Fracas". Bret Morrison, Grace Matthews and Santos Ortega reprised their roles as "Lamont Cranston/The Shadow", "Margo Lane" and "Commissioner Weston". Ken Roberts also returned as the announcer.

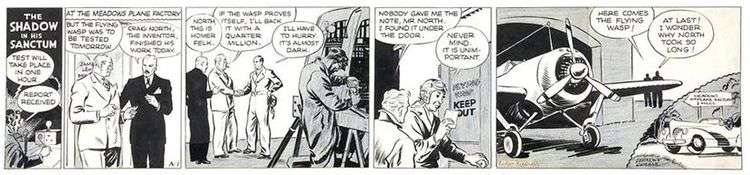

Comic strips, comic books, graphic novels

The Shadow has been adapted for the comics several times during his long history; his first comics appearance was on June 17, 1940 as a syndicated daily newspaper comic strip offered through the Ledger Syndicate. The strip's story continuity was written by Walter B. Gibson, with plot lines adapted from the Shadow pulps, and the strip was illustrated by Vernon Greene. Due to pulp paper shortages during World War II and the growing amount of space required for war news from both the European and Pacific fronts, the strip was canceled on June 13, 1942, after two years and nine adventures had been published. The Shadow daily was collected decades later in two comic book series from two different publishers (see below), first in 1988 and then in 1999.

To both cross-promote The Shadow and attract a younger audience to their other pulp magazines, Street & Smith published 101 issues of the comic book Shadow Comics from Vol. 1, #1 - Vol. 9, #5 (March 1940 - Sept. 1949).[15] A Shadow story led off each issue, with the remainder of the stories being strips based on other Street & Smith pulp heroes.

In Mad #4 (April–May 1953), The Shadow was spoofed by Harvey Kurtzman and Will Elder. Their character was called "The Shadow'" (with an apostrophe), which is short for "Lamont Shadowskeedeeboomboom". The Shadow' is invisible as in the radio series; when he makes himself visible, he is attired like the pulp character but is very short and ugly; his companion, "Margo Pain", begs him to cloud her mind again. Throughout the story, someone is trying to kill Margo, getting "Shad", as she calls him, into various predicaments: he is beaten up by gangsters and has a piano dropped on him. He tricks Margo into an outhouse (the interior of which is an impossibly huge mansion) which he demolishes with dynamite. As The Shadow' gleefully presses the detonator, he says, "NOBODY knows to whom the voice of the invisible Shadow belongs!" This story was reprinted in The Brothers Mad (ibooks, New York, 2002, ISBN 0-7434-4482-5).

Lamont Shadowskeedeeboomboom returned in Mad #14 (August 1954) to guest-star in "Manduck the Magician", a spoof by Harvey Kurtzman and Will Elder of the Mandrake the Magician comic strip. In this story, Lamont Shadowskeedeeboomboom lures Manduck and Loathar to his home on the pretense of wanting to buy 100 cases of Manduck's snake oil; in reality, he has learned that Manduck also has "the secret power to cloud men's minds, and so in order to keep [his] secret exclusive", he intends to destroy Manduck. A battle of hypnotic gesturing ensues, during which Loathar somehow also has the power. Each character turns himself or one or two of the others into one of the other characters, culminating in three Manducks who all gesture hypnotically, causing a massive explosion that leaves only one Manduck who may or may not be the real one. Manduck's girlfriend, Narda, declares that whomever he really is, "Only one of you is dear to my heart and that one is... the one with the most loot!" This story was reprinted in Mad Strikes Back! (ibooks, New York, 2002, ISBN 0-7434-4478-7).

During the superhero revival of the 1960s, Archie Comics published an eight-issue series, The Shadow (Aug. 1964 - Sept. 1965), under the company's Mighty Comics imprint. In the first issue, The Shadow was loosely based on the radio version, but with blond hair. In issue #2 (Sept. 1964), the character was transformed into a campy, heavily muscled superhero in a green and blue costume by writer Robert Bernstein and artist John Rosenberger. Later issues of this eight-issue series were written by Superman co-creator Jerry Siegel.[16]

During the mid-1970s, DC Comics published an "atmospheric interpretation" of the character by writer Dennis O'Neil and artist Michael Kaluta[17] in a 12-issue series (Nov. 1973 - Sept. 1975). Kaluta drew issues 1-4 and 6 and was followed by Frank Robbins and then E. R. Cruz. Attempting to be faithful to both the pulp-magazine and radio-drama character, the series guest-starred fellow pulp fiction hero the Avenger in issue #11.[18] The Shadow also appeared in DC's Batman #253 (Nov. 1973), in which Batman teams with an aging Shadow and calls the famous crime fighter his "greatest inspiration". In Batman #259 (Dec. 1974), Batman again meets The Shadow, and we learn The Shadow saved Bruce Wayne's life when the future Batman was a boy.

The Shadow is also referenced in DC's Detective Comics #446 (1975), page 4, panel 2: Batman, out of costume and in disguise as an older night janitor, makes a crime fighting acknowledgement, in a thought balloon, to the Shadow.

In 1986, another DC adaptation was developed by Howard Chaykin. This four issue mini-series, The Shadow: Blood and Judgement, brought The Shadow to modern-day New York. While initially successful,[19] this version proved unpopular with traditional Shadow fans[20] because it depicted The Shadow using Uzi submachine guns and rocket launchers, as well as featuring a strong strain of black comedy and extreme violence throughout.[21]

The Shadow, set in our modern era, was continued in 1987 as a monthly DC comics series by writer Andy Helfer (editor of the mini-series); it was drawn primarily by artists Bill Sienkiewicz (issues 1-6) and Kyle Baker (issues 8-19 and two Shadow Annuals).

In 1988 O'Neil and Kaluta, with inker Russ Heath, returned to The Shadow with the Marvel Comics graphic novel The Shadow: Hitler's Astrologer, set during World War II. This one-shot appeared in both hardcover and trade paperback editions.

The Vernon Greene/Walter Gibson Shadow newspaper comic strip from the early 1940s was collected by Malibu Graphics (Malibu Comics) under their Eternity Comics imprint, beginning with the first issue of Crime Classics dated July 1988. Each cover was illustrated by Greene and colored by one of Eternity's colorists. A total of 13 issues appeared featuring just the black-and-white daily until the final issue, dated November, 1989. Some of the Shadow story lines were contained in one issue, while others were continued over into the next. When a Shadow story ended, another tale would begin in the same issue. This back-to-back format continued until the final 13th issue, when the strip story lines ended.

Dave Stevens' nostalgic comics series Rocketeer contains a great number of pop culture references to the 1930s. Various characters from the Shadow pulps make appearances in the storyline published in the Rocketeer Adventure Magazine, including The Shadow's famous alter ego Lamont Cranston. Two issues were published by Comico in 1988 and 1989, but the third and final instalment did not appear until years later, finally appearing in 1995 from Dark Horse Comics. All three issues were then collected by Dark Horse into a slick trade paperback titled The Rocketeer: Cliff's New York Adventure (ISBN 1-56971-092-9).

In 1989, DC released in graphic novel hardcover reprinting five issues (#1-4 and 6 by Dennis O'Neil and Michael Kaluta) of their 1970s series as The Private Files of The Shadow. The volume also featured a new Shadow adventure drawn by Kaluta.

From 1989 to 1992, DC published a new Shadow series, The Shadow Strikes, written by Gerard Jones and Eduardo Barreto. This series was set in the 1930s and returned The Shadow to his pulp origins. During its run, it featured The Shadow's first team-up with Doc Savage, another popular hero of the pulp magazine era. Both characters appeared together in a four-issue story that crossed back and forth between each character's DC comic series. The Shadow Strikes often led The Shadow into encounters with well-known celebrities of the 1930s, such as Albert Einstein, Amelia Earhart, Charles Lindbergh, union organizer John L. Lewis, and Chicago gangsters Frank Nitti and Jake Guzik. In issue #7, The Shadow meets a radio announcer named Grover Mills, a character based on the young Orson Welles, who has been impersonating The Shadow on the radio. The character's name is taken from Grover's Mill, New Jersey, the name of the small town where the Martians land in Welles' 1938 radio broadcast of The War of the Worlds. When Shadow rights holder Condé Nast increased its licensing fee, DC concluded the series after 31 issues and one annual; it became the longest running Shadow comic series since Street and Smith's original 1940s series.

During the early-to-mid-1990s, Dark Horse Comics acquired the rights to the Shadow from Condé Nast. It published the Shadow miniseries The Shadow: In the Coils of Leviathan (four issues) in 1993, and The Shadow: Hell's Heat Wave (three issues) in 1995. In the Coils of Leviathan was later collected by Dark Horse in 1994 as a trade paperback. Both series were written by Joel Goss and Michael Kaluta, and drawn by Gary Gianni. A one-shot Shadow issue The Shadow and the Mysterious Three was also published by Dark Horse in 1994, again written by Joel Goss and Michael Kaluta, with Stan Manoukian and Vince Roucher taking over the illustration duties but working from Kaluta's layouts. A comics adaptation of the 1994 film The Shadow was published in two issues by Dark Horse as part of the movie's merchandising campaign. The script was by Goss and Kaluta and drawn by Kaluta. It was collected and published in England by Boxtree as a graphic novel tie-in for the film's British release. Emulating DC's earlier team-up, Dark Horse also published a two-issue mini-series in 1995 called The Shadow and Doc Savage: The Case of the Shrieking Skeletons. It was written by Steve Vance, and illustrated by Manoukian and Roucher. Both issues' covers were drawn by Rocketeer creator Dave Stevens. A final Dark Horse Shadow team-up was published in 1995: the single issue Ghost and the Shadow, written by Doug Moench, pencilled by H. M. Baker, and inked by Bernard Kolle.

The Shadow made an uncredited cameo appearance in issue #2 of DC's 1996 four issue mini-series Kingdom Come, re-released as a trade paperback in 1997. The Shadow appears in the nightclub scene standing in the background next to The Question and Rorschach.

The early 1940s Shadow newspaper daily strip was reprinted by Avalon Communications under their ACG Classix imprint. The Shadow daily began appearing in the first issue of Pulp Action comics. It carried no monthly date or issue number on the cover, only a 1999 copyright and a Pulp Action #1 notation at the bottom of the inside cover. Each issue's cover is a colorized panel blow-up, taken from one of the reprinted strips. The eighth issue uses for its cover a Shadow serial black-and-white film still, with several hand-drawn alterations. The first issue of Pulp Action is devoted entirely to reprinting the Shadow daily, but subsequent issues began offering back-up stories not involving The Shadow in every issue. These Shadow strip reprints stopped with Pulp Action's eighth issue, before the story was complete; the last issue carries a 2000 copyright date.

In August 2011, Dynamite licensed The Shadow from Condé Nast for on-going comic book series and several limited run miniseries.[22] Their first on-going series was written by Garth Ennis and illustrated by Aaron Campbell; it debuted on April 19, 2012. This series ran for 26 issues; the regular series ended in May 2014, but a prologue issue #0 was published in July 2014. Dynamite followed with the release of an eight-issue miniseries, Masks, teaming the 1930s Shadow with Dynamite's other pulp hero comic book adaptations, the Spider, The Green Hornet and Kato, and a 1930s Zorro, plus four other heroes of the pulp era from Dynamite's comics line-up. Dynamite offered a second eight-issue Shadow miniseries, The Shadow Year One, followed by the team-up miniseries The Shadow/Green Hornet: Dark Nights, and a Shadow miniseries set in the modern era, The Shadow Now. In August 2015, Dynamite Entertainment launched volume 2 of The Shadow, a new ongoing series is written by Cullen Bunn and drawn by Giovanni Timpano. Additional Dynamite Entertainment Shadow comics adaptations and team-ups continue.

Films

The Shadow character has been adapted for film shorts and films.

Shadow film shorts (1931–1932)

In 1931 Universal Pictures created a series of six film shorts based on the popular Detective Story Hour radio program, narrated by The Shadow. The first short, A Burglar to the Rescue, was filmed in New York City and features the voice of The Shadow on radio, Frank Readick. Beginning with the second short, The House of Mystery, the series was produced in Hollywood without the voice of Readick as The Shadow; it was followed by The Circus Show-Up and three additional shorts the following year with other voice actors portraying The Shadow.

The Shadow Strikes (1937)

The film The Shadow Strikes was released in 1937, starring Rod La Rocque in the title role. Lamont Cranston assumes the secret identity of "The Shadow" in order to thwart an attempted robbery at an attorney's office. Both The Shadow Strikes (1937) and its sequel, International Crime (1938), were released by Grand National Pictures.

International Crime (1938)

La Rocque returned the following year in International Crime. In this version, reporter Lamont Cranston is an amateur criminologist and detective who uses the name of "The Shadow" as a radio gimmick. Thomas Jackson portrayed Police Commissioner Weston, and Astrid Allwyn was cast as Phoebe Lane, Cranston's assistant.

The Shadow (1940)

The Shadow, a 15-chapter movie serial produced by Columbia Pictures and starring Victor Jory, premiered in theaters in 1940. The serial's villain, The Black Tiger, is a criminal mastermind who sabotages rail lines and factories across the United States. Lamont Cranston must become his shadowy alter ego in order to unmask the criminal and halt his fiendish crime spree. As The Shadow, Jory wears an all-black suit and cape, as well as a black bandana that helps conceal his facial features.

The Shadow Returns, etc. (1946)

Low-budget motion picture studio Monogram Pictures produced a trio of quickie Shadow B-movie features in 1946 starring Kane Richmond: The Shadow Returns, Behind the Mask and The Missing Lady. Richmond's Shadow wore all black, including a trench coat, a wide-brimmed fedora, and a full face-mask similar to the type worn by movie serial hero The Masked Marvel, instead of the character's signature black cape with red lining and red scarf.

Invisible Avenger (1958)

Episodes of a television pilot shot in 1957 were edited into the 1958 theatrical feature Invisible Avenger, rereleased in 1962 as Bourbon Street Shadows.[23][24]

The Shadow (1994)

.jpg)

In 1994 the character was adapted once again into a feature film, The Shadow, starring Alec Baldwin as Lamont Cranston and Penelope Ann Miller as Margo Lane. As the film opens, Cranston has become the evil and corrupt Yin-Ko (literally "Dark Eagle"), a brutal warlord and opium smuggler in early 1930s Mongolia. Yin-Ko is kidnapped by agents of the mysterious Tulku, who begins to reform the warlord using the psychic power of his evolved mind to restore Cranston's humanity. The Tulku also teaches him the ability to "cloud men's minds" using psychic power in order to fight evil in the world. Cranston eventually returns to his native New York City and takes up the guise of the mysterious crime fighter "The Shadow", in payment to humanity for his past evil misdeeds: "Who knows what evil lurks in the hearts of men? The Shadow knows..."

His nemesis in the film is adapted from the pulp series' long-running Asian villain (and for the film, a fellow telepath), the evil Shiwan Khan (John Lone), a descendant of Genghis Khan. He seeks to finish his ancestor's legacy of conquering the world by first destroying New York City, using a newly developed atomic bomb, in a show of his power. Khan nearly succeeds in this, but he is thwarted by The Shadow in a final psychic duel of death: Cranston, as The Shadow, imposes his will on, and defeats, Khan during a psychokinetically enhanced battle in a mirrored room, which has exploded into thousands of flying mirror shards. Focusing his mind's psychokinetic power, The Shadow flips a flying piece of jagged mirror in mid-air and then hurls it directly at a spot on Khan's forehead; this does not kill him, it only renders him unconscious. To save both the warlord and the world, The Shadow secretly arranges with one of his agents, an administrative doctor at an unidentified New York asylum for the criminally insane, to have Khan locked away permanently in a padded cell; Khan's badly-injured frontal lobe, which controlled his psychic powers, having been surgically removed.

The film combines elements from The Shadow pulp novels and comic books with the aforementioned ability to cloud minds described only on the radio show. In the film Alec Baldwin, as The Shadow, wears a red-lined black cloak and a long red scarf that covers his mouth and chin; he also wears a black, double-breasted trench coat and a wide-brimmed, black slouch hat; as in the pulp novels, he is armed with a pair of Browning .45-caliber semi-automatic pistols that for the film have longer barrels, are nickel-plated, and have ivory handles. The film also displays a first: Cranston's ability to conjure a false face whenever he is in his guise as The Shadow, in keeping with his physical portrayal in the pulps and the comics.

The film was financially and critically unsuccessful.[25][26]

Sam Raimi Shadow feature film

On December 11, 2006, the website SuperHero Hype reported that director Sam Raimi and Michael Uslan would co-produce a new Shadow film for Columbia Pictures.[27]

On October 16, 2007, Raimi stated, "I don't have any news on The Shadow at this time, except that the company that I have with Josh Donen, my producing partner, we've got the rights to The Shadow. I love the character very much and we're trying to work on a story that'll do justice to the character."[28]

On August 23, 2012, the website ShadowFan reported that during a Q&A session at San Diego's 2012 Comic-Con, director Sam Raimi, when asked about the status of his Shadow film project, stated they had not been able to develop a good script and the film would not be produced as planned.

Television

Two attempts were made to adapt the character to television. The first, in 1954, was titled The Shadow, and starred Tom Helmore as Lamont Cranston.

The second attempt in 1958 was titled The Invisible Avenger; it never aired. The two episodes produced were compiled into a theatrical film and released with the same title. It was re-released with additional footage in 1962 as Bourbon Street Shadows. Starring Richard Derr as The Shadow, the film depicts Lamont Cranston investigating the murder of a New Orleans bandleader. The film is notable as the second directorial effort of James Wong Howe, who directed only one of the two unaired episodes.

Influence on superheroes and other media

When Bob Kane and Bill Finger first developed Kane's "Bat-Man", Finger suggested they pattern the character after pulp mystery men such as The Shadow.[3] Finger then used "Partners of Peril"[29]—a Shadow pulp written by Theodore Tinsley—as the basis for Batman's debut story, "The Case of the Chemical Syndicate."[30] Finger later publicly acknowledged that "my first Batman script was a take-off on a Shadow story"[31] and that "Batman was originally written in the style of the pulps."[32] This influence was further evident with Batman showing little remorse over killing or maiming criminals and not being above using firearms.[32] Decades later, noted comic book writer Dennis O'Neil would have Batman and The Shadow meet in Batman #253 (November 1973) and Batman #259 (December 1974) to solve crimes.[33] In the former, Batman acknowledged that The Shadow was his biggest influence[34] and in the latter, The Shadow reveals to Batman that he knows his true identity of Bruce Wayne, but assures him that his secret is safe with him.

Additionally, characters such as Batman resemble Lamont Cranston's alter ego.[35]

The Shadow is also mentioned by science fiction author Philip José Farmer as being a member of his widespread and hero-filled Wold Newton family.

Welles's sinister laughter and Shadow opening dialog line is parodied in the January 1946 Heckle and Jeckle debut cartoon, The Talking Magpies.

Alan Moore has credited The Shadow as one of the key influences for the creation of V, the title character in his DC Comics miniseries V for Vendetta,[36][37] that later became a Warner Bros. feature film released in 2006.

See also

- Condé Nast, owner of The Shadow intellectual property

- Doctor Sax

- List of The Shadow episodes

References

Notes

- 1 2 3 4 "History of The Shadow". Retrieved 2008-01-11.

- ↑ Stedman, Raymond William (1977). Serials: Suspense and Drama By Installment. University of Oklahoma Press. p. 154. ISBN 978-0806116952.

The definite article in The Shadow's name was always capitalized in the pulp adventures

- 1 2 Secret Origins of Batman (Part 1 of 3) - Retrieved on January 13, 2008.

- ↑ "The Shadow: A Short Radio History". Retrieved 2008-03-23.

- 1 2 3 4 Anthony Tollin. "Foreshadowings," The Shadow #5: The Salamanders and The Black Falcon; February 2007, Nostalgia Ventures.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Tollin, Anthony (June 2006). "Spotlight on The Shadow". The Shadow #1: the Golden Vulture and Crime Insured. Nostalgia Ventures: 4–5.

- ↑ Xavier Fournier, Super-héros : une histoire française, Huginn Muninn, 2014, p. 70-73

- ↑ "The Shadow in Review". Retrieved 2008-02-02.

- ↑ p.28 Wormser, Richard & Skutch, Ira How to Become a Complete Non-Entity: A Memoir 2006 iUniverse

- ↑ Tollin, Anthony (February 2007). "The Shadow on the Radio". The Shadow. Nostalgia Ventures (#5: The Salamanders and The Black Falcon).

- ↑ Grams, Jr., Martin (2011). The Shadow: The History and Mystery of the Radio Program, 1930-1954. OTR Publishing, LLC. pp. 55–57. ISBN 978-0-9825311-1-2.

- ↑ "The Shadow's return to network airwaves began with the first episode, Deathhouse Rescue". Retrieved 2014-04-11.

- 1 2 3 Will Murray. "Introducing Margo Lane", p. 127, The Shadow #4: Murder Master and The Hydra; January 2007, Nostalgia Ventures.

- ↑ Anthony Tollin. "Voices from the Shadows," p. 120, The Shadow #5: The Salamanders and The Black Falcon; February 2007, Nostalgia Ventures.

- ↑ Grand Comics Database: Shadow Comics

- ↑ Grand Comics Database: The Shadow (1964 series)

- ↑ McAvennie, Michael; Dolan, Hannah, ed. (2010). "1970s". DC Comics Year By Year A Visual Chronicle. Dorling Kindersley. p. 157. ISBN 978-0-7566-6742-9.

Writer Denny O'Neil and artist Mike Kaluta presented their interpretation of writer Walter B. Gibson's pulp-fiction mystery man of the 1930s

- ↑ Grand Comics Database: The Shadow (1973 series)

- ↑ "the series sold well -- earning an early graphic novel treatment and leading to an ongoing series by Andy Helfer, Bill Sienkiewicz and Kyle Baker". Kiel Phegley, Howard Chaykin: The Art of The Shadow. In Comic Book Resources, Feb. 28, 2012, page found 2012-03-30.

- ↑ "... Simply for bucks because he has confessed in interviews that he never cared a gram about the character, auteur Howard Chaykin has taken The Shadow and turned him, in a four-issue mini-series, into a sexist, calloused, clearly psychopathic obscenity. Rather than simply ignoring characters from the Shadow's past, Chaykin has murdered them in full view... And when Mr. Chaykin was asked why he had this penchant for drawing pictures of thugs jamming .45's into the mouths of terrified women, Mr. Chaykin responded that the only readers who might object to this bastardization of a much-beloved fictional character were 'forty-year-old boys'. These comics bear the legend FOR MATURE READERS. For MATURE read DERANGED." Harlan Ellison, essay titled "In Which Youth Goeth Before A Fall", in The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction, August 1986.

- ↑ Chaykin, in an interview after the book came out, had this to say: "I thought the book was well received by the people I cared about. Comic book fandom is evenly divided between people who like comics in a general way and are fans of comics in general, and then there's an entire spate of juvenilists who attach themselves to the old joke about the Golden Age of comics. 'What's the Golden Age of comics? 12!' There's this tremendous idea that their tastes were formed and refined at 12, and frankly, I'm not interested in supporting that sensibility. By the same token, if I'm going to be doing a mature readers product, I don't feel the need to stand by the standards of a 12-year-old sensibility. I certainly feel the pain of the people who were offended by the material, but fuck 'em. Life is hard all over. I was hired to do a job, and I feel I did a pretty damn good job with the material I had to work with. I'm happy with the work. I know that I antagonize and piss people off, but it's fine. Who cares?" Kiel Phegley, Howard Chaykin: The Art of The Shadow. In Comic Book Resources, Feb. 28, 2012, page found 2012-03-30.

- ↑ Siegel, Lucas (August 17, 2011). "Dynamite Returns THE SHADOW to Comics After 16-Year Hiatus" Newsarama.

- ↑ p. 128 Radio Daily-Television Daily Volume 78

- ↑ Shimeld, Thomas J. (2003). Walter B. Gibson and the Shadow. McFarland & Co. p. 86.

- ↑ "The Shadow (1994)." Rotten Tomatoes.

- ↑ "20 Worst Comic-Book Movies Ever. The Shadow, Alec Baldwin." Entertainment Weekly

- ↑ "Columbia & Raimi Team on The Shadow". SuperHeroHype.

- ↑ Rotten, Ryan (2007-10-16). "Sam Raimi on Spider-Man 4 and The Shadow". Superherohype.com. Coming Soon Media, ltd. Retrieved 2008-07-28.

- ↑ The Shadow Vol. 9 - "Foreshadowing The Batman" - Retrieved on January 13, 2008.

- ↑ Secret Origins of Batman (Part 2 of 3) - Retrieved on January 13, 2008.

- ↑ Steranko, James (1972). The Steranko History of Comics. Crown Publishing Group. ISBN 0-7851-2116-1.

- 1 2 Daniels, Les (1999). Batman: The Complete History. Chronicle Books. p. 25. ISBN 0-8118-4232-0.

- ↑ "The Shadow Comic Cover Gallery: Comic Crossover".

- ↑ http://www.shadowsanctum.net/comic/comic_images/batman-253_p20.jpg

- ↑ Boichel, Bill (1991). "Batman: Commodity as Myth." The Many Lives of the Batman: Critical Approaches to a Superhero and His Media. London: Routledge. pp. 6–7. ISBN 0-85170-276-7.

- ↑ Moore, Alan (1990). V for Vendetta: Behind the Painted Smile. DC Comics.

- ↑ Boudreaux, Madelyn (2006-10-17). "Annotation of References in Alan Moore's V For Vendetta". Retrieved 2008-07-28.

Bibliography

- Cox, J. Randolph. Man of Magic & Mystery, A Guide to the Work of Walter B. Gibson, Scarecrow Press, 1998. ISBN 0-8108-2192-3. (Comprehensive history and career bibliography of Gibson's works.)

- Eisgruber, Jr., Frank. Gangland's Doom, The Shadow of the Pulps, Starmont House, 1985. ISBN 0-930261-74-7.

- Gibson, Walter B., Tollin, Anthony. The Shadow Scrapbook, Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1979. ISBN 0-15-681475-7. (Comprehensive history of The Shadow in all media forms up through the late 1970s.)

- Goulart, Ron. Cheap Thrills: An Informal History of the Pulp Magazine, Arlington House, 1972. ISBN 0870001728

- Murray, Will. Duende History of the Shadow Magazine, Odyssey Publications, 1980. ISBN 0-933752-21-0.

- Overstreet, Robert. The Official Overstreet Comic Book Price Guide, 35th Edition., House of Collectibles, 2005. ISBN 0-375-72107-X. (Lists all Shadow comics published to date.)

- Sampson, Robert. The Night Master, Pulp Press, 1982. ISBN 0-934498-08-3.

- Shimfield, Thomas J. Walter B. Gibson and The Shadow. McFarland & Company, 2003. ISBN 0-7864-1466-9. (Comprehensive Walter Gibson biography with an emphasis on The Shadow.)

- Steranko, James. Steranko's History of the Comics, Vol. 1, Supergraphics, 1970. No ISBN.

- Steranko, James, (1972), Steranko's History of the Comics, Vol. 2, Supergraphics, 1972. No ISBN.

- Steranko, James. Unseen Shadows, Supergraphics, 1978. No ISBN. (Collection of Steranko's detailed black-and-white cover roughs, including alternate/unused versions, done for the Shadow novel reprints from Pyramid Books and Jove/HBJ.)

- Van Hise, James. The Serial Adventures of the Shadow, Pioneer Books, 1989. No ISBN.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: The Shadow |

- The Shadow: Master of Darkness

- ThePulp.Net: The Shadow

- The Shadow on IMDb

- The Shadow at the Comic Book DB

- The Shadow on Way Back When

- The Shadow on Outlaws Old Time Radio Corner

.jpg)