Shilha literature

Shilha or Tashelhiyt is a Berber language spoken in southwestern Morocco.

Oral literature

Shilha, like other varieties of Berber, has an extensive body of oral literature in a wide variety of genres. Fables and animal stories often revolve around the character of the jackal (uššn); other genres include legends, imam/taleb stories, riddles, and tongue-twisters. A large number of oral texts, as well as ethnographic texts on the customs and traditions of the Išlḥiyn have been recorded and published since the end of the 19th century, mainly by European linguists.

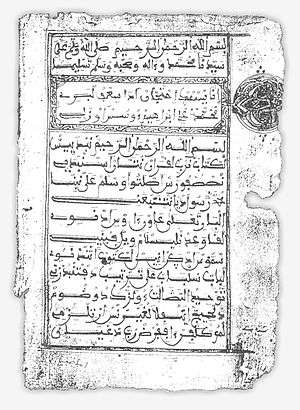

Traditional manuscript literature

Shilha is one of only a handful of living African languages which possesses a literary tradition which can be traced back to the pre-colonial era.[1] Numerous texts, written in Arabic script, are preserved in manuscripts, dating from the past four centuries. The earliest datable text is a sizeable compendium of lectures on the “religious sciences” (lɛulum n ddin) composed in metrical verses by Ibrāhīm al-Ṣanhājī, a.k.a. Brahim Aẓnag (d. 1597 CE). The most well-known writer of this tradition is Muḥammad al-Hawzālī, a.k.a. Mḥmmd Awzal (ca. 1680-1749 CE). The longest extant text in Shilha is a commentary (sharḥ) on al-Ḥawḍ, Awzal's manual of Mālikī law; the commentary, entitled al-Manjaʽ “the Pasture” is from the hand of al-Ḥasan ibn Mubārak al-Tamuddiztī, a.k.a. Lḥsn u Mbark u Tmuddizt (d. 1899 CE). Important collections of Shilha manuscripts are preserved in Aix-en-Provence (the fonds Arsène Roux) and Leiden. Virtually all manuscripts are religious in content, and their main purpose was to provide instruction to the illiterate common people (of course, with literate scholars serving as teachers). Many of the texts are in versified form in order to facilitate memorisation and recitation. Apart from purely religious texts (almost all of them in versified form), there are also narratives in verse (e.g. Lqist n Yusf “the story of Joseph”, Lɣazawat n Susata “the Conquest of Sousse”), odes on the pleasures of drinking tea, collections of medicinal recipes (in prose), bilingual glossaries, etc.

The premodern written language differs in some aspects from normal spoken Shilha. For example, it is common for the manuscript texts to contain a mix of dialectal features not found in any single modern dialect. The language of the manuscripts also contains a higher number of Arabic words than the modern spoken form, a phenomenon that has been called arabisme poétique.[2] Other characteristics of manuscript verse text, which are probably adopted from oral conventions, are the use of plural verb forms instead of singular forms, uncommon plural nouns formed with the prefix ida, use of stopgaps such as daɣ “again”, hann and hatinn “lo!”, etc. These conventions can be linked to the need to make the text conform to fixed metrical formulae.

Modern literature

A modern, printed literature in Tashelhiyt has sprung up since the 1970s.

See also

References

- ↑ Classical Ethiopian (Ge'ez) has a large and old literary heritage. There are some Malagasy manuscripts that date from the 17th century, and a few Swahili manuscripts that may date from the 17th or 18th centuiry. Hausamanuscripts probably all date from the 19th century and after.

- ↑ Term introduced by Galand-Pernet (1972:137).

Bibliography

- Boogert, N. van den (1997). The Berber Literary Tradition of the Sous. With an edition and translation of "The Ocean of Tears" by Muḥammad Awzal (d. 1749). De Goeje Fund, Vol. XXVII. Leiden: NINO. ISBN 90-6258-971-5.

- Galand-Pernet, P. (1972). Recueil de poèmes chleuhs. Paris: Klincksieck. ISBN 2-252-01415-6.