Sheberghan

| Sheberghan شبرغان | |

|---|---|

| City | |

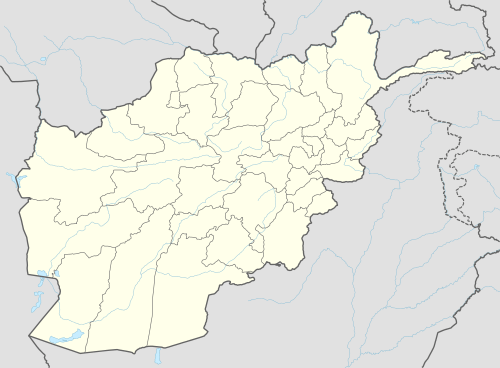

Sheberghan Location in Afghanistan | |

| Coordinates: 36°39′54″N 65°45′07.2″E / 36.66500°N 65.752000°ECoordinates: 36°39′54″N 65°45′07.2″E / 36.66500°N 65.752000°E | |

| Country |

|

| Province | Jowzjan Province |

| Elevation | 250 m (820 ft) |

| Population (2006) | |

| • City | 148,329 |

| • Urban | 175,599 [1] |

| [2] | |

| Time zone | Afghanistan Standard Time (UTC+4:30) |

Sheberghān or Shaburghān (Pastho, Persian: شبرغان), also spelled Shebirghan and Shibarghan, is the capital city of the Jowzjan Province in northern Afghanistan.

The city of Sheberghan has a population of 175,599.[3] It has 4 districts and a total land area of 7,335 Hectar.[4] The total number of dwellings in Sheberghan are 19,511.[5]

Location

Sheberghan is located along the Safid River banks, about 130 km (81 mi) west of Mazari Sharif on the national primary ring road Herat-Kandahar-Kabul-Mazari Sharif-Sheberghan-Maymana-Herat. Sheberghan airport is situated between Sheberghan and Aqchah.

Etymology

City's name is corruption of the classical name, Shaporgân, "[king] Shapur town." The king is Shapur II or Saporis II, the Sassanian king of Persia. The city's name is similar to Peshawar, Beh Shapor, "the good deed of Shapor."

Ethnography

The city is the single most important Uzbek-dominated city in all of Afghanistan. But, although Uzbek is the mother language of a majority of the inhabitants, the city is multi-lingual. Large numbers of Tajiks, Hazaras, Pashtuns, and Arabs live in the city per se.

The Sheberghan "Arabs," however, are all Persian-speaking and have been so since time immemorial. However, they claim an Arab identity. There are other such Persian-speaking "Arabs" to the east, between Shebergan, Mazar-i Sharif, Kholm and Kunduz living in pockets. Their self-identification as Arabs is largely based on their tribal identity and may in fact point to the 7th and 8th centuries migration to this and other Central Asian locales of many Arab tribes from Arabia in the wake of the Islamic conquests of the region.[6]

In 1856, J. P. Ferrier wrote:

"Shibberghan is a town containing 12,000 souls. Uzbeks the former being in a great majority."

History

Sheberghan was once a flourishing settlement along the Silk Road. In 1978, Soviet archaeologists discovered the famed Bactrian Gold in the village of Tillia Tepe outside Sheberghan. In the 13th century Marco Polo visited the city and later wrote about its honey sweet melons. Sheberghan became the capital of an independent Uzbek khanate that was allotted to Afghanistan by the 1873 Anglo-Russian border agreement.

Sheberghan has for millennia been the focal point of power in the northeast corner of Bactria. It still sits astride the main route between Balkh and Herat, and controls the direct route north to the Oxus/Amu Darya, about 90 km away, as well as the important branch route south to Sar-e Pol.

In 1856, J. P. Ferrier reports:

The town has a citadel, in which the governor Rustem Khan resides, but there are no other fortifications. It is surrounded by good gardens and excellent cultivation. The population of Shibberghan has a high character for bravery, and I may safely say it is one of the finest towns in Turkistan on this side of the Oxus, enjoying, besides its other advantages, an excellent climate. It is, however, subject to one very serious inconvenience: the supply of water, on which all this prosperity depends, comes from the mountains in the Khanat of Sirpool; and as there are frequent disputes between the tribes inhabiting it and those living in the town, a complete interruption of the supply is often threatened, and a war follows, to the very great injury of the place. Shibberghan maintains permanently a force of 2000 horse and 500-foot, but, in case of necessity, the town can arm 6000 men.[7]

The heavily fortified town of Yemshi-tepe, just five kilometres to the northeast of modern Sheberghan, on the road to Akcha, is only about 500 metres (550 yards) from the famous necropolis of Tillya-tepe, where an immense treasure was excavated from the graves of the local royal family by a joint Soviet-Afghan archaeological effort from 1969 to 1979.

In 1977 a Soviet-Afghan archaeological team began serious excavations 5 km north of the town for relics. They had uncovered mud-brick columns and a cross-shaped altar of an ancient temple dating back to at least 1000 BC.

Six royal tombs were excavated at Tillia Tepe revealing a vast amount of gold and other treasures. Several coins dated up to the early 1st century CE, with none dated later.

Sheberghan has been proposed as the site of ancient Xidun, one of the five xihou, or divisions, of the early Kushan Empire.[8]

Sheberghan was the site of the Dasht-i-Leili massacre in December 2001 during the U.S. invasion of Afghanistan where between 250 and 3,000 (depending on sources) Taliban prisoners were shot and/or suffocated to death in metal truck containers, while being transferred by American and Northern Alliance soldiers from Kunduz to Sheberghan prison.

Sheberghan was the stronghold of Uzbek warlord General Abdul Rashid Dostum, who had been vying with his Tajik rival General Mohammed Atta for control of northern Afghanistan.

The name of the city might be a derivative of Shaporgan, meaning "City of Shapor." Shapur, was the name of two Sasanian kings, both of whom built a great number of cities. However, Shapur I was the governor of the eastern provinces of the empire, and it is more likely that he is the builder of a roadway between a few important cities. These include, in possible addition to Sheberghan, Nishapur ("Good deed of Shapor") and Bishapur in Iran and Peshawar in Pakistan

Land Use

Sheberghan is a Trading and Transit Hub in northern Afghanistan.[9] Agriculture accounts for 50% of the 7,335 hectares within the municipal boundaries.[10] Residential land is 23% and largely clustered in the central area, but well distributed through the four districts.[11]

Climate

Sheberghan has a hot semi-arid climate (Köppen climate classification: BSh)[12] with hot summers and cool winters. There is moderate rainfall from January to March, but the rest of the year is dry, especially the summer.

| Climate data for Sheberghan | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 22.4 (72.3) |

24.2 (75.6) |

30.9 (87.6) |

35.4 (95.7) |

41.5 (106.7) |

46.0 (114.8) |

47.5 (117.5) |

44.3 (111.7) |

40.6 (105.1) |

36.4 (97.5) |

30.6 (87.1) |

25.6 (78.1) |

47.5 (117.5) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 6.8 (44.2) |

9.3 (48.7) |

15.8 (60.4) |

23.7 (74.7) |

31.1 (88) |

36.9 (98.4) |

38.9 (102) |

37.2 (99) |

32.0 (89.6) |

24.0 (75.2) |

16.7 (62.1) |

10.6 (51.1) |

23.58 (74.45) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 2.0 (35.6) |

4.9 (40.8) |

10.5 (50.9) |

17.3 (63.1) |

23.2 (73.8) |

28.8 (83.8) |

31.0 (87.8) |

28.6 (83.5) |

23.1 (73.6) |

16.4 (61.5) |

10.0 (50) |

5.4 (41.7) |

16.77 (62.18) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −1.3 (29.7) |

1.3 (34.3) |

5.7 (42.3) |

11.5 (52.7) |

15.1 (59.2) |

19.4 (66.9) |

22.2 (72) |

20.0 (68) |

15.1 (59.2) |

9.8 (49.6) |

4.6 (40.3) |

1.5 (34.7) |

10.41 (50.74) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −20.5 (−4.9) |

−25.7 (−14.3) |

−9.4 (15.1) |

−7.5 (18.5) |

5.3 (41.5) |

8.5 (47.3) |

12.9 (55.2) |

11.6 (52.9) |

4.3 (39.7) |

−2.4 (27.7) |

−8.5 (16.7) |

−15 (5) |

−25.7 (−14.3) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 42.3 (1.665) |

44.3 (1.744) |

56.4 (2.22) |

25.9 (1.02) |

11.2 (0.441) |

0.2 (0.008) |

0.0 (0) |

0.0 (0) |

0.2 (0.008) |

6.6 (0.26) |

13.6 (0.535) |

29.8 (1.173) |

230.5 (9.074) |

| Average rainy days | 5 | 6 | 9 | 6 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 38 |

| Average snowy days | 5 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 12 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 78 | 76 | 71 | 65 | 47 | 34 | 31 | 32 | 35 | 46 | 61 | 74 | 54.2 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 115.3 | 124.1 | 162.3 | 198.2 | 297.9 | 364.3 | 365.9 | 346.1 | 304.6 | 242.9 | 175.8 | 125.7 | 2,823.1 |

| Source: NOAA (1964-1983) [13] | |||||||||||||

Economy

Sheberghan is surrounded by irrigated agricultural land.

With Soviet assistance, exploitation of Afghanistan's natural gas reserves began in 1967 at the Khowaja Gogerak field, 15 kilometers east of Sheberghan in Jowzjan Province. The field's reserves were thought to be 67 billion cubic meters. In 1967, the Soviets also completed a 100-kilometer gas pipeline linking Keleft in the Soviet Union with Sheberghan.

To demonstrate how natural gas reserves could be used as an alternative to expensive petroleum imports, the United States Department of Defense spent $43m on a natural gas filling station.[14]

Sheberghan is important in the energy infrastructure of Afghanistan:

- The Zomrad Sai Oilfield is situated near Sheberghan

- The Sheberghan Topping Plant processes crude oil for consumption in heating boilers in Kabul, Mazari Sharif and Sheberghan

- The Jorqaduk, Khowaja Gogerak, and Yatimtaq gas fields are all located within 20 miles (32 km) of Sheberghan.

See also

Footnotes

- ↑ "The State of Afghan Cities report2015". Archived from the original on 2015-10-31.

- ↑ "Jawzjan" (PDF).

- ↑ "The State of Afghan Cities report2015". Archived from the original on 2015-10-31.

- ↑ "The State of Afghan Cities report 2015".

- ↑ "The State of Afghan Cities report 2015".

- ↑ Barfield (1982), p. ?

- ↑ Ferrier (1856), p. 202.

- ↑ Hill (2009), pp. 29, 332-341.

- ↑ "The State of Afghan Cities report 2015".

- ↑ "The State of Afghan Cities report 2015".

- ↑ "The State of Afghan Cities report 2015".

- ↑ "Climate: شبرغان - Climate graph, Temperature graph, Climate table". Climate-Data.org. Retrieved 3 September. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ "Sheberghan Climate Normals 1964-1983". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved December 25, 2012.

- ↑ "Afghan fuel station cost $43m, US military report says". BBC News. Retrieved 3 November 2015.

References

- Barfield, Thomas J. (1982). The Central Asian Arabs of Afghanistan: Pastoral Nomadism in Transition.

- Dupree, Nancy Hatch. (1977). An Historical Guide to Afghanistan. 1st Edition: 1970. 2nd Edition (1977). Revised and Enlarged. Afghan Tourist Organization, 1977. Chapter 21 "Maimana to Mazar-i-Sharif."

- Ferrier, J. P. (1856), Caravan Journeys and Wanderings in Persia, Afghanistan, Turkistan and Beloochistan. John Murray, London.

- Hill, John E. (2009). Through the Jade Gate to Rome: A Study of the Silk Routes during the Later Han Dynasty, 1st to 2nd Centuries CE. BookSurge, Charleston, South Carolina. ISBN 978-1-4392-2134-1.

- Leriche, Pierre. (2007). "Bactria: Land of a Thousand Cities." In: After Alexander: Central Asia before Islam. Eds. Georgina Hermann and Joe Cribb. (2007). Proceedings of the British Academy 133. Oxford University Press.

- Sarianidi, Victor. (1985). The Golden Hoard of Bactria: From the Tillya-tepe Excavations in Northern Afghanistan. Harry N. Abrams, New York.