Shepard tone

A Shepard tone, named after Roger Shepard, is a sound consisting of a superposition of sine waves separated by octaves. When played with the bass pitch of the tone moving upward or downward, it is referred to as the Shepard scale. This creates the auditory illusion of a tone that continually ascends or descends in pitch, yet which ultimately seems to get no higher or lower.[1]

Construction

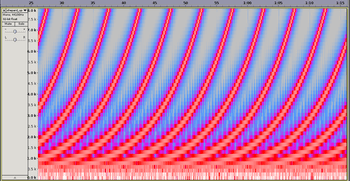

Each square in the figure indicates a tone, with any set of squares in vertical alignment together making one Shepard tone. The color of each square indicates the loudness of the note, with purple being the quietest and green the loudest. Overlapping notes that play at the same time are exactly one octave apart, and each scale fades in and fades out so that hearing the beginning or end of any given scale is impossible. As a conceptual example of an ascending Shepard scale, the first tone could be an almost inaudible C4 (middle C) and a loud C5 (an octave higher). The next would be a slightly louder C♯4 and a slightly quieter C♯5; the next would be a still louder D4 and a still quieter D5. The two frequencies would be equally loud at the middle of the octave (F♯4 and F♯5), and the eleventh tone would be a loud B4 and an almost inaudible B5 with the addition of an almost inaudible B3. The twelfth tone would then be the same as the first, and the cycle could continue indefinitely. (In other words, each tone consists of two sine waves with frequencies separated by octaves; the intensity of each is e.g. a gaussian function of its separation in semitones from a peak frequency, which in the above example would be B4. According to Shepard, "(...) almost any smooth distribution that tapers off to subthreshold levels at low and high frequencies would have done as well as the cosine [gaussian] curve actually employed."[1])

|

A descending Shepard–Risset glissando

|

| Problems playing this file? See media help. | |

The acoustical illusion can be constructed by creating a series of overlapping ascending or descending scales. Similar to a barber's pole, the basic concept is shown in Figure 1.

The scale as described, with discrete steps between each tone, is known as the discrete Shepard scale. The illusion is more convincing if there is a short time between successive notes (staccato or marcato instead of legato or portamento).

Jean-Claude Risset subsequently created a version of the scale where the tones glide continuously, and it is appropriately called the continuous Risset scale or Shepard–Risset glissando. When done correctly, the tone appears to rise (or fall) continuously in pitch, yet return to its starting note. Risset has also created a similar effect with rhythm in which tempo seems to increase or decrease endlessly.[2]

Tritone paradox

A sequentially played pair of Shepard tones separated by an interval of a tritone (half an octave) produces the tritone paradox. In this auditory illusion, first reported by Diana Deutsch in 1986, the scales may be heard as either descending or ascending.[3] Shepard had predicted that the two tones would constitute a bistable figure, the auditory equivalent of the Necker cube, that could be heard ascending or descending, but never both at the same time.[1] Deutsch later found that perception of which tone was higher depended on the absolute frequencies involved, and that different listeners may perceive the same pattern as being either ascending or descending.[4]

Examples

- In a film by Shepard and E. E. Zajac, a Shepard tone accompanies the ascent of an analogous Penrose stair.[5]

- In his book Gödel, Escher, Bach: An Eternal Golden Braid, Douglas Hofstadter explains how Shepard scales can be used on the Canon a 2, per tonos in Bach's Musical Offering (called the Endlessly Rising Canon by Hofstadter[6]:10) for making the modulation end in the same pitch instead of an octave higher.[6]:717–719

- In Super Mario 64, a modified Shepard tone is incorporated into the music of the endless staircase, the staircase to the penultimate room in the castle.[7] Much like a real Shepard tone, the staircase itself gives players the impression that they are constantly running upwards, when in reality the game has simply locked them in place, and turning around reveals that they were actually running in place halfway up the stairs.

- In the film The Dark Knight and its follow-up The Dark Knight Rises, a Shepard tone was used to create the sound of the Batpod, a motorcycle that the filmmakers didn't want to change gear and tone abruptly but to constantly accelerate.[8]

- Used as a compositional technique for digital orchestral music on a piece by composer Renaldo Ramai entitled "The Journey".[9]

- The Shepard tone was a key aspect in Stephin Merritt's song "A Million Faces", composed for NPR's "Project Song".[10]

- The ending of the song "Echoes" from the album Meddle by Pink Floyd features a Shepard tone that fades out to a wind sound (actually a white noise processed through a tape echo unit).

- The Austrian composer Georg Friedrich Haas uses Shepard tone effect towards the end of his orchestral piece In Vain.

- The song "Slow Moving Trains" from Godspeed You! Black Emperor's album F♯ A♯ ∞ begins with the sound of a Shepard tone.

- In the film Dunkirk, a Shepard tone created the illusion of an ever increasing moment of intensity across intertwined storylines.[11]

- The Shepard Tone is sometimes used to build tension in electronic dance music. As the so called 'build-up' in progressive dance music is a very important aspect of the musical structure, the Shepard Tone can be used as an effect to raise the song's energy to a certain level. Examples of modern day dance music (progressive house) where a Shepard Tone has been used as rising effect are 'Leave The World Behind',[12] (produced by the Swedish House Mafia and Laidback Luke) and 'Born To Rage'[13] (produced by Dada Life)

- The track "Endlessly Downwards" by Beatsystem from the 1995 album em:t 2295 uses a descending Shepard tone throughout its 3'25" running time.[14]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 Shepard, Roger N. (December 1964). "Circularity in Judgements of Relative Pitch". Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 36 (12): 2346–53. doi:10.1121/1.1919362.

- ↑ Risset rhythm

- ↑ Deutsch, Diana (1986). "A musical paradox" (PDF). Music Perception. 3: 275–280. doi:10.2307/40285337. Retrieved 26 May 2012.

- ↑ Deutsch, D. (1992). "Some New Pitch Paradoxes and their Implications". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 336 (1278): 391–397. PMID 1354379. doi:10.1098/rstb.1992.0073.

- ↑ Shepard, Roger N.; Zajac, Edward E. (1967). A Pair of Paradoxes. AT&T Bell Laboratories.

- 1 2 Hofstadter, Douglas (1980). Gödel, Escher, Bach: An Eternal Golden Braid (1st ed.). Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-005579-7.

- ↑ "Shepard Tones". Get High Now. 2009. Retrieved 18 March 2013.

- ↑ King, Richard (4 February 2009). "'The Dark Knight' sound effects". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 12 September 2012.

- ↑ Ramai, Renaldo. The Journey.

- ↑ Stephin Merritt: Two Days, 'A Million Faces' (video). NPR. 4 November 2007. Retrieved 9 October 2015.

It turns out I was thinking about a Shepard tone, the illusion of ever-ascending pitches.

- ↑ Haubursin, Christopher (26 July 2017). "The sound illusion that makes Dunkirk so intense". Vox.com. Retrieved 27 July 2017.

- ↑ Axwell, Ingrosso, Angello, Laidback Luke ft. Deborah Cox - Leave The World Behind (Original).

- ↑ Dada Life - Born To Rage (USA Version).

- ↑ "Endlessly Downward, by Beatsystem". Em:t records. Retrieved 2017-07-27.

External links

- Yadegari, Shahrokh D. (25 August 1992). "The Shepard Tone (The partials of a Shepard tone)". Self-similar Synthesis: On the Border Between Sound and Music (Master thesis). Archived from the original on 2013-02-08.

- BBC science show, Bang Goes the Theory, explains the Shepard Tone

- Demonstration of discrete Shepard tone (requires Macromedia Shockwave)

- Visualization of the Shepard Effect using Java

- A demonstration of a rising Shepard Scale as a ball bounces endlessly up a Penrose staircase (and down)

- Shepard tone Keyboard on CodePen