Saka

| Part of a series on |

| Indo-European topics |

|---|

|

|

|

Origins |

|

Archaeology Pontic Steppe Caucasus East-Asia Eastern Europe Northern Europe Pontic Steppe Northern/Eastern Steppe Europe

South-Asia Steppe Europe Caucasus India |

|

Peoples and societies Indo-Aryans Iranians Europe East-Asia Europe Indo-Aryan Iranian |

|

|

The Saka or Saca (Persian: old Sakā, mod. ساکا; Sanskrit: Śaka; Ancient Greek: Σάκαι, Sákai; Latin: Sacae; Chinese: 塞, old *Sək, mod. Sāi)[lower-alpha 1] was the term used in Persian and Sanskrit sources for the Scythians, a large group of Eastern Iranian nomadic tribes on the Eurasian Steppe.[2][3][4] Modern scholars usually use the term Saka to refer to Iranians of the Eastern Steppe and the Tarim Basin.[5] René Grousset wrote that they formed a particular branch of the "Scytho-Sarmatian family" originating from nomadic Iranian peoples of the northwestern steppe in Eurasia.[6] They migrated into Sogdiana and Bactria in Central Asia and then to the northwest of the Indian subcontinent where they were known as the Indo-Scythians. In the Tarim Basin and Taklamakan desert region of Northwest China, they settled in Khotan and Kashgar which were at various times vassals to greater powers, such as the Han and Tang dynasties of Imperial China.

Usage of name

Modern debate about the identity of the "Saka" is partly from ambiguous usage of the word by ancient, non-Saka authorities. According to Herodotus, the Persians gave the name "Saka" to all Scythians.[7] However, Pliny the Elder (Gaius Plinius Secundus, AD 23–79) claims that the Persians gave the name Sakai only to the Scythian tribes "nearest to them".[8] The Scythians to the far north of Assyria were also called the Saka suni (Saka or Scythian sons) by the Persians. The Assyrians, of the time of Esarhaddon, record campaigning against a people they called in the Akkadian the Ashkuza or Ishhuza.[9] However, modern scholarly consensus is that the Saka language, ancestor to the Pamir languages in northern India and Khotanese in Xinjiang, China belongs to the Scythian languages.[10]

Another people, the Gimirrai,[9] who were known to the ancient Greeks as the Cimmerians, were closely associated with the Sakas. In ancient Hebrew texts, the Ashkuz (Ashkenaz) are considered to be a direct offshoot from the Gimirri (Gomer).[11]

The Saka were regarded by the Babylonians as synonymous with the Gimirrai; both names are used on the trilingual Behistun inscription, carved in 515 BC on the order of Darius the Great.[12] (These people were reported to be mainly interested in settling in the kingdom of Urartu, later part of Armenia, and Shacusen in Uti Province derives its name from them.[13]) The Behistun inscription initially only gave one entry for saka, they were however further differentiated later into three groups:[14][15][16]

- the Sakā tigraxaudā – "Saka with pointy hats/caps",

- the Sakā haumavargā – interpreted as "haoma-drinking saka" but there are other suggestions,[14][17][18]

- the Sakā paradraya – "Saka beyond the sea", a name added after Darius' campaign into Western Scythia north of the Danube.[14]

An additional term is found in two inscriptions elsewhere:[19]

- the Sakā para Sugdam – "Saka beyond Sugda (Sogdiana)", a term was used by Darius for the people who formed the limits of his empire at the opposite end to Kush (the Ethiopians), therefore should be located at the eastern edge of his empire.[14][20]

The Sakā paradraya were the western Scythians (European Scythians) or Sarmatians. Both the Sakā tigraxaudā and Sakā haumavargā are thought to be located in Central Asia east of the Caspian Sea.[14] Sakā haumavargā is considered to be the same as Amyrgians, the Saka tribe in closest proximity to Bactria and Sogdiana. It has been suggested that the Sakā haumavargā may be the Sakā para Sugdam, therefore Sakā haumavargā is argued by some to be located further east than the Sakā tigraxaudā, perhaps at the Pamirs or Xinjiang, although Jaxartes is considered to be their more likely location given that the name says "beyond Sogdiana" rather than Bactria.[14]

In the modern era, the archaeologist Hugo Winckler (1863–1913) was the first to associate the Sakas with the Scyths. J. M. Cook, in The Cambridge History of Iran, states: "The Persians gave the single name Sakā both to the nomads whom they encountered between the Hunger steppe and the Caspian, and equally to those north of the Danube and Black Sea against whom Darius later campaigned; and the Greeks and Assyrians called all those who were known to them by the name Skuthai (Iškuzai). Sakā and Skuthai evidently constituted a generic name for the nomads on the northern frontiers."[14] Persian sources often treat them as a single tribe called the Saka (Sakai or Sakas), but Greek and Latin texts suggest that the Scythians were composed of many sub-groups.[21][22] Modern scholars usually use the term Saka to refer to Iranian-speaking tribes who inhabited the Eastern Steppe and the Tarim Basin.[5][23]

History

The Saka people were an Iranian people who spoke a language belonging to the Iranian branch of the Indo-European languages. They are known to the ancient Greeks as Scythians and are attested in historical and archaeological records dating to around the 8th century BC.[24] In the Achaemenid-era Old Persian inscriptions found at Persepolis, dated to the reign of Darius I (r. 522-486 BC), the Saka are said to have lived just beyond the borders of Sogdiana.[25] Likewise an inscription dated to the reign of Xerxes I (r. 486-465 BC) has them coupled with the Dahae people of Central Asia.[25] The contemporary Greek historian Herodotus noted that the Achaemenid Persians called all of the Iranian Scythian peoples as the Saka.[25]

Greek historians wrote of the wars between the Saka and the Medes, as well as their wars against Cyrus the Great of the Persian Achaemenid Empire where Saka women were said to fight alongside their men.[26] According to Herodotus, Cyrus the Great confronted the Massagetae, a people related to the Saka,[27] while campaigning to the east of the Caspian Sea and was killed in the battle in 530 BC.[28] Darius the Great also waged wars against the eastern Sakas, who fought him with three armies led by three kings according to Polyaenus.[29] In 520–519 BC, Darius I defeated the Sakā tigraxaudā tribe and captured their king Skunkha (depicted as wearing a pointed hat in Behistun).[5] The territories of Saka were absorbed into the Achaemenid Empire as part of Chorasmia that included much of Amu Darya (Oxus) and Syr Darya (Jaxartes),[30] and the Saka then supplied the Persian army with large number of mounted bowmen in the Achaemenid wars.[16] They were also mentioned as among those who resisted Alexander the Great's incursions into Central Asia.[26]

The Shakya clan of India, to which Siddhārtha Gautama Śākyamuni Buddha belonged, has been identified as Sakas by Michael Witzel[31] and Christopher I. Beckwith.[32]

The Saka were known as the Sak (塞) in ancient Chinese records.[33][34] These records indicate that they originally inhabited the Ili and Chu River valleys of modern Kyrgyzstan and Kazakhstan. In the Chinese Book of Han, the area was called the "land of the Sak", i.e. the Saka.[35] The exact date of the Saka's arrival in the valleys of the rivers Ili and Chu in Central Asia is unclear, perhaps it was just before the reign of Darius I.[35] Around 30 Saka tombs in the form of kurgans (burial mounds) have also been found in the Tian Shan area dated to between 550–250 BC. Indications of Saka presence have also been found in the Tarim Basin region, possibly as early as the 7th century BC.[24]

The Saka were pushed out of the Ili and Chu River valleys by the Indo-European Yuezhi, thought by some to be Tocharians. An account of the movement of these people is given in Sima Qian's Shiji. The Yuezhi, who originally lived between Tängri Tagh (Tian Shan) and Dunhuang of Gansu, China,[36] were assaulted and forced to flee from the Hexi Corridor of Gansu by the Mongolic forces of the Xiongnu ruler Modu Chanyu, who conquered the area in 177-176 BC.[37][38][39][40] In turn the Yuezhi were responsible for attacking and pushing the Sai (i.e. Saka) west into Sogdiana, where around 140 and 130 BC the latter crossed the Syr Darya into Bactria. The Saka also moved southwards towards to the Pamirs and northern India where they settled in Kashmir, and eastwards to settle in some of the oasis city-states of Tarim Basin sites like Yanqi (焉耆, Karasahr) and Qiuci (龜茲, Kucha).[41][42] The Yuezhi, themselves under attacks from another nomadic tribe the Wusun in 133-132 BC, moved again from the Ili River and Chu River valleys and occupied the country of "Daxia" (大夏) or Bactria.[35][43]

The ancient Greco-Roman geographer Strabo noted that the four tribes that took down the Bactrians in the Greek and Roman account – the Asioi, Pasianoi, Tokharoi and Sakaraulai – came from land north of Syr Darya where the Ili and Chu valleys are located.[6][35] Identification of these four tribes varies, but Sakaraulai may indicate an ancient Saka tribe, the Tokharoi is possibly the Yuezhi, and while the Asioi had been proposed to be groups such as the Wusun or Alans.[6][44]

Grousset wrote of the migration of the Saka: "the Saka, under pressure from the Yueh-chih [Yuezhi], overran Sogdiana and then Bactria, there taking the place of the Greeks." Then, "Thrust back in the south by the Yueh-chih," the Saka occupied "the Saka country, Sakastana, whence the modern Persian Seistan."[6] According to Harold W. Bailey, the territory of Drangiana (in modern Afghanistan and Pakistan) became known as "Land of the Sakas", and was called Sakastāna in the Persian language of contemporary Iran, in Armenian as Sakastan, with similar equivalents in Pahlavi, Greek, Sogdian, Syriac, Arabic, and the Middle Persian tongue used in Turfan, Xinjiang, China.[25] This is attested in a contemporary Kharosthi inscription found on the Mathura lion capital belonging to the Saka kingdom of the Indo-Scythians (200 BC - 400 AD) in northern India,[25] roughly the same time the Chinese record that the Saka had invaded and settled the country of Jibin 罽賓 (i.e. Kashmir, of modern-day India and Pakistan).[45]

Migrations of the 2nd and 1st century BC have left traces in Sogdia and Bactria, but they cannot firmly be attributed to the Saka, similarly with the sites of Sirkap and ancient Taxila in ancient India. The rich graves at Tillya Tepe in Afghanistan are seen as part of a population affected by the Saka.[46]

Indo-Scythians

The region in modern Afghanistan and Pakistan where the Saka moved to become known as "land of the Saka" or Sakastan.[25] The Sakas also captured Gandhara and Taxila, and migrated to North India.[47] An Indo-Scythians kingdom was established in Mathura (200 BC - 400 AD).[25] Weer Rajendra Rishi, an Indian linguist, identified linguistic affinities between Indian and Central Asian languages, which further lends credence to the possibility of historical Sakan influence in North India.[47][48] According to historian Michael Mitchiner, the Abhira tribe were a Saka people cited in the Gunda inscription of the Western Satrap Rudrasimha I dated to 181 CE.[49]

Kingdom of Khotan

Obv: Kharosthi legend, "Of the great king of kings, king of Khotan, Gurgamoya.

Rev: Chinese legend: "Twenty-four grain copper coin". British Museum

The Kingdom of Khotan was a Saka city state in on the southern edge of the Tarim Basin. As a consequence of the Han–Xiongnu War spanning from 133 BC to 89 AD, the Tarim Basin region of Xinjiang in Northwest China, including Khotan and Kashgar, fell under Han Chinese influence, beginning with the reign of Emperor Wu (r. 141-87 BC) of the Han Dynasty.[50][51] During the later Tang dynasty, the region once again came under Chinese suzerainty with the campaigns of conquest by Emperor Taizong of Tang (r. 626-649).[52] From the late 8th to 9th centuries, the region changed hands between the Chinese Tang Empire and the rival Tibetan Empire.[53][54] However, by the early 11th century the region fell to the Muslim Turkic peoples of the Kara-Khanid Khanate, which led to both the Turkification of the region as well as its conversion from Buddhism to Islam.

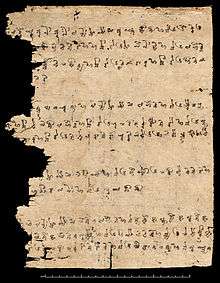

Archaeological evidence and documents from Khotan and other sites in the Tarim Basin provided information on the language spoken by the Saka.[25][55] The official language of Khotan was initially Gandhari Prakrit written in the Kharosthi script, and coins from Khotan dated to the 1st century bear dual inscriptions in Chinese and Gandhari Prakrit, indicating links of Khotan to both India and China.[56] Surviving documents however suggest that an Iranian language was used by the people of the kingdom for a long time Third-century AD documents in Prakrit from nearby Shanshan record the title for the king of Khotan as hinajha (i.e. "generalissimo"), a distinctively Iranian-based word equivalent to the Sanskrit title senapati, yet nearly identical to the Khotanese Saka hīnāysa attested in later Khotanese documents.[56] This, along with the fact that the king's recorded regnal periods were given as the Khotanese kṣuṇa, "implies an established connection between the Iranian inhabitants and the royal power," according to the Professor of Iranian Studies Ronald E. Emmerick.[56] He contended that Khotanese-Saka-language royal rescripts of Khotan dated to the 10th century "makes it likely that the ruler of Khotan was a speaker of Iranian."[56] Furthermore, he argued that the early form of the name of Khotan, hvatana, is connected semantically with the name Saka.[56]

Later Khotanese-Saka-language documents, ranging from medical texts to Buddhist literature, have been found in Khotan and Tumshuq (northeast of Kashgar).[57] Similar documents in the Khotanese-Saka language dating mostly to the 10th century have been found in Dunhuang.[58]

Although the ancient Chinese had called Khotan Yutian (于闐), another more native Iranian name occasionally used was Jusadanna (瞿薩旦那), derived from Indo-Iranian Gostan and Gostana, the names of the town and region around it, respectively.[59]

Shule Kingdom

Much like the neighboring people of the Kingdom of Khotan, people of Kashgar, the capital of Shule, spoke Saka, one of the Eastern Iranian languages.[60] According to the Book of Han, the Saka split and formed several states in the region. These Saka states may include two states to the northwest of Kashgar, and Tumshuq to its northeast, and Tushkurgan south in the Pamirs.[61] Kashgar also conquered other states such as Yarkand and Kucha during the Han dynasty, but in its later history, Kashgar was controlled by various empires, including Tang China,[62][63] before it became part of the Turkic Kara-Khanid Khanate in the 10th century. In the 11th century, according to Mahmud al-Kashgari, some non-Turkic languages like the Kanchaki and Sogdian were still used in some areas in the vicinity of Kashgar,[64] and Kanchaki is thought to belong to the Saka language group.[61] It is believed that the Tarim Basin was linguistically Turkified before the 11th century ended.[65]

Language

Attestations of Saka show that it was an Eastern Iranian language. Both dialects contain many borrowings from the Middle Indo-Aryan Prakrit, but also share features with modern Wakhi and Pashto.[66] The Issyk inscription, a short fragment on a silver cup found in the Issyk kurgan (modern Kazakhstan) is believed to be an early example of Saka, constituting one of very few autochthonous epigraphic traces of that language. The inscription is in a variant of the Kharoṣṭhī script. Harmatta identifies the dialect as Khotanese Saka, tentatively translating its as: "The vessel should hold wine of grapes, added cooked food, so much, to the mortal, then added cooked fresh butter on".[67]

The linguistic heartland of the Saka language was the Kingdom of Khotan, which had two dialects, corresponding to the major settlements at Khotan (modern Hotan) and Tumshuq (Tumxuk).[68][69] The Saka heartland was gradually conquered during the Turkic expansion, beginning in the 4th century and the area was gradually "Turkified" linguistically (under the Uighurs).

See also

Notes

References

Citations

- ↑ 1.

- ↑ West 2009, pp. 713–717

- ↑ "Scythian". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Retrieved January 18, 2015.

- ↑ P. Lurje, “Yārkand”, Encyclopædia Iranica, online edition

- 1 2 3 Beckwith, Christopher (8 May 2011). Empires of the Silk Road (PDF). Princeton University Press. p. 68. ISBN 978-0691150345.

- 1 2 3 4 Grousset, Rene (1970). The Empire of the Steppes. Rutgers University Press. pp. 29–31. ISBN 0-8135-1304-9.

- ↑ Herodotus Book VII, 64

- ↑ Naturalis Historia, VI, 19, 50

- 1 2 Westermann, Claus (1984). : A Continental Commentary. John J. Scullion (trans.). Minneapolis. p. 506. ISBN 0800695003.

- ↑ Kuz'mina, Elena E. (2007). The Origin of the Indo Iranians. Edited by J.P. Mallory. Leiden, Boston: Brill, pp 381-382. ISBN 978-90-04-16054-5.

- ↑ "The sons of Gomer were Ashkenaz, Riphath,[a] and Togarmah." See also the entry for Ashkenaz in Young, Robert. Analytical Concordance to the Bible. McLean, Virginia: Mac Donald Publishing Company. ISBN 0-917006-29-1.

- ↑ George Rawlinson, noted in his translation of History of Herodotus, Book VII, p. 378

- ↑ Kurkjian, Vahan M. (1964). A History of Armenia. New York: Armenian General Benevolent Union of America. p. 23.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 J. M. Cook (6 June 1985). "The Rise of the Achaemenids and Establishment of Their Empire". In Ilya Gershevitch. The Cambridge History of Iran, Volume 2. Cambridge University Press; Reissue edition. pp. 253–255. ISBN 978-0521200912.

- ↑ Briant, Pierre (29 July 2006). From Cyrus to Alexander: A History of the Persian Empire. Eisenbrauns. p. 173. ISBN 978-1575061207.

- 1 2 M. A. Dandamayev. History of Civilizations of Central Asia Volume II: The development of sedentary and nomadic civilizations: 700 BC to AD 250. UNESCO. pp. 44–46. ISBN 978-8120815407.

- ↑ Muhammad A. Dandamaev, Vladimir G. Lukonin (21 August 2008). The Culture and Social Institutions of Ancient Iran. Cambridge University Press. p. 334. ISBN 978-0521611916.

- ↑ "Haumavargā". Encyclopedia Iranica.

- ↑ The Cambridge Ancient History, Volume IV. Cambridge University Press. 24 November 1988. p. 173. ISBN 978-0521228046.

- ↑ Briant, Pierre (29 July 2006). From Cyrus to Alexander: A History of the Persian Empire. Eisenbrauns. p. 178. ISBN 978-1575061207.

This is Kingdom which I hold, from the Scythians [Saka] who are beyond Sogdiana, thence unto Ethiopia [Cush]; from Sind, thence unto Sardis.

- ↑ Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society ... – Google Books. 2007-04-06. Retrieved 2010-12-30.

- ↑ Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain & Ireland By Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland-page-323

- ↑ L. T. Yablonsky. "The Archaeology of Eurasian Nomads". In Donald L. Hardesty. ARCHAEOLOGY – Volume I. EOLSS. p. 383. ISBN 9781848260023.

- 1 2 J. P. mallory. "Bronze Age Languages of the Tarim Basin" (PDF). Penn Museum.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Bailey, H.W. (1996) [14 April 1983]. "Chapter 34: Khotanese Saka Literature". In Ehsan Yarshater. The Cambridge History of Iran, Vol III: The Seleucid, Parthian, and Sasanian Periods, Part 2 (reprint ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 1230–1231. ISBN 978-0521246934.

- 1 2 L. T. Yablonsky. "The Archaeology of Eurasian Nomads". In Donald L. Hardesty. ARCHAEOLOGY – Volume I. EOLSS. p. 383. ISBN 9781848260023.

- ↑ Barbara A. West. Encyclopedia of the Peoples of Asia and Oceania. p. 516.

- ↑ Cunliffe, Barry (24 September 2015). By Steppe, Desert, and Ocean: The Birth of Eurasia. Oxford University Press. p. 206. ISBN 978-0199689170.

- ↑ A. Sh. Shahbazi,. "Amorges". Encyclopaedia Iranica.

- ↑ Cunliffe, Barry (24 September 2015). By Steppe, Desert, and Ocean: The Birth of Eurasia. Oxford University Press. p. 235. ISBN 978-0199689170.

- ↑ Jayarava Attwood, Possible Iranian Origins for the Śākyas and Aspects of Buddhism. Journal of the Oxford Centre for Buddhist Studies 2012 (3): 47-69 https://www.academia.edu/25950011/Possible_Iranian_Origins_for_the_%C5%9A%C4%81kyas_and_Aspects_of_Buddhism

- ↑ Christopher I. Beckwith, "Greek Buddha: Pyrrho's Encounter with Early Buddhism in Central Asia", 2016, pp 1-21

- ↑ Zhang Guang-da. History of Civilizations of Central Asia Volume III: The crossroads of civilizations: AD 250 to 750. UNESCO. p. 283. ISBN 978-8120815407.

- ↑ H. W. Bailey. Indo-Scythian Studies: Being Khotanese Texts. Cambridge University Press. p. 67. ISBN 978-0521118736.

- 1 2 3 4 Yu Taishan (June 2010), "The Earliest Tocharians in China" in Victor H. Mair (ed), Sino-Platonic Papers, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, University of Pennsylvania Department of East Asian Languages and Civilizations, p. 13.

- ↑ Mallory, J. P. & Mair, Victor H. (2000). The Tarim Mummies: Ancient China and the Mystery of the Earliest Peoples from the West. Thames & Hudson. London. p. 58. ISBN 0-500-05101-1.

- ↑ Torday, Laszlo. (1997). Mounted Archers: The Beginnings of Central Asian History. Durham: The Durham Academic Press, pp 80-81, ISBN 978-1-900838-03-0.

- ↑ Yü, Ying-shih. (1986). "Han Foreign Relations," in The Cambridge History of China: Volume I: the Ch'in and Han Empires, 221 B.C. – A.D. 220, 377-462. Edited by Denis Twitchett and Michael Loewe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp 377-388, 391, ISBN 978-0-521-24327-8.

- ↑ Chang, Chun-shu. (2007). The Rise of the Chinese Empire: Volume II; Frontier, Immigration, & Empire in Han China, 130 B.C. – A.D. 157. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, pp 5-8 ISBN 978-0-472-11534-1.

- ↑ Di Cosmo, Nicola. (2002). Ancient China and Its Enemies: The Rise of Nomadic Power in East Asian History. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 174-189, 196-198, 241-242 ISBN 978-0-521-77064-4.

- ↑ Yu Taishan (June 2010), "The Earliest Tocharians in China" in Victor H. Mair (ed), Sino-Platonic Papers, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, University of Pennsylvania Department of East Asian Languages and Civilizations, pp. 13-14, 21-22.

- ↑ Benjamin, Craig. "The Yuezhi Migration and Sogdia".

- ↑ Bernard, P. (1994). "The Greek Kingdoms of Central Asia". In Harmatta, János. History of civilizations of Central Asia, Volume II. The development of sedentary and nomadic civilizations: 700 B.C. to A.D. 250. Paris: UNESCO. pp. 96–126. ISBN 92-3-102846-4.

- ↑ Baumer, Christoph (30 November 2012). The History of Central Asia: The Age of the Steppe Warriors. I.B.Tauris. p. 296. ISBN 978-1780760605.

- ↑ Ulrich Theobald. (26 November 2011). "Chinese History - Sai 塞 The Saka People or Soghdians." ChinaKnowledge.de. Accessed 2 September 2016.

- ↑ Yaroslav Lebedynsky, P. 84

- 1 2 Sulimirski, Tadeusz (1970). The Sarmatians. Volume 73 of Ancient peoples and places. New York: Praeger. pp. 113–114.

The evidence of both the ancient authors and the archaeological remains point to a massive migration of Sacian (Sakas)/Massagetan tribes from the Syr Daria Delta (Central Asia) by the middle of the second century B.C. Some of the Syr Darian tribes; they also invaded North India.

- ↑ Rishi, Weer Rajendra (1982). India & Russia: linguistic & cultural affinity. Roma. p. 95.

- ↑ Mitchiner, Michael (1978). The ancient & classical world, 600 B.C.-A.D. 650. Hawkins Publications ; distributed by B. A. Seaby. p. 634. ISBN 978-0-904173-16-1.

- ↑ Loewe, Michael. (1986). "The Former Han Dynasty," in The Cambridge History of China: Volume I: the Ch'in and Han Empires, 221 B.C. – A.D. 220, 103–222. Edited by Denis Twitchett and Michael Loewe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp 197-198. ISBN 978-0-521-24327-8.

- ↑ Yü, Ying-shih. (1986). "Han Foreign Relations," in The Cambridge History of China: Volume I: the Ch'in and Han Empires, 221 B.C. – A.D. 220, 377-462. Edited by Denis Twitchett and Michael Loewe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp 410-411. ISBN 978-0-521-24327-8.

- ↑ Xue, Zongzheng (薛宗正). (1992). History of the Turks (突厥史). Beijing: Zhongguo shehui kexue chubanshe, p. 596-598. ISBN 978-7-5004-0432-3; OCLC 28622013

- ↑ Beckwith, Christopher. (1987). The Tibetan Empire in Central Asia. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, pp 36, 146. ISBN 0-691-05494-0.

- ↑ Wechsler, Howard J.; Twitchett, Dennis C. (1979). Denis C. Twitchett; John K. Fairbank, eds. The Cambridge History of China, Volume 3: Sui and T'ang China, 589–906, Part I. Cambridge University Press. pp. 225–227. ISBN 978-0-521-21446-9.

- ↑ Ronald E. Emmerick. "Khotanese and Tumshuqese". In Gernot Windfuhr. Iranian Languages. Routledge. p. 377.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Emmerick, R. E. (14 April 1983). "Chapter 7: Iranian Settlement East of the Pamirs". In Ehsan Yarshater. The Cambridge History of Iran, Vol III: The Seleucid, Parthian, and Sasanian Periods, Part 1. Cambridge University Press; Reissue edition. pp. 265–266. ISBN 978-0521200929.

- ↑ Bailey, H.W. (1996). "Khotanese Saka Literature". In Ehsan Yarshater. The Cambridge History of Iran, Vol III: The Seleucid, Parthian, and Sasanian Periods, Part 2 (reprint ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 1231–1235.

- ↑ Hansen, Valerie (2005). "The Tribute Trade with Khotan in Light of Materials Found at the Dunhuang Library Cave" (PDF). Bulletin of the Asia Institute. 19: 37–46.

- ↑ Ulrich Theobald. (16 October 2011). "City-states Along the Silk Road." ChinaKnowledge.de. Accessed 2 September 2016.

- ↑ Xavier Tremblay, "The Spread of Buddhism in Serindia: Buddhism Among Iranians, Tocharians and Turks before the 13th Century", in The Spread of Buddhism, eds Ann Heirman and Stephan Peter Bumbacker, Leiden: Koninklijke Brill, 2007, p. 77.

- 1 2 Ahmad Hasan Dani; B. A. Litvinsky; Unesco (1 January 1996). History of Civilizations of Central Asia: The crossroads of civilizations, A.D. 250 to 750. UNESCO. pp. 283–. ISBN 978-92-3-103211-0.

- ↑ Whitfield 2004, p. 47.

- ↑ Wechsler, Howard J.; Twitchett, Dennis C. (1979). Denis C. Twitchett; John K. Fairbank, eds. The Cambridge History of China, Volume 3: Sui and T'ang China, 589–906, Part I. Cambridge University Press. pp. 225–228. ISBN 978-0-521-21446-9.

- ↑ Scott Cameron Levi; Ron Sela (2010). Islamic Central Asia: An Anthology of Historical Sources. Indiana University Press. pp. 72–. ISBN 0-253-35385-8.

- ↑ Akiner (28 October 2013). Cultural Change & Continuity In. Routledge. pp. 71–. ISBN 978-1-136-15034-0.

- ↑ Litvinsky, Boris Abramovich; Vorobyova-Desyatovskaya, M.I (1999). "Religions and religious movements". History of civilizations of Central Asia. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 421–448. ISBN 8120815408.

- ↑ Harmatta, János (20 August 1994). History of Civilizations of Central Asia: The Development of Sedentary and Nomadic Civilizations. UNESCO. pp. 420–421. ISBN 978-9231028465.

- ↑ Sarah Iles Johnston, Religions of the Ancient World: A Guide, Harvard University Press, 2004. pg 197

- ↑ Edward A Allworth,Central Asia: A Historical Overview,Duke University Press, 1994. pp 86.

Bibliography

- Akiner (28 October 2013). Cultural Change & Continuity In Central Asia. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-136-15034-0.

- Bailey, H. W. 1958. "Languages of the Saka." Handbuch der Orientalistik, I. Abt., 4. Bd., I. Absch., Leiden-Köln. 1958.

- Bailey, H. W. (1979). Dictionary of Khotan Saka. Cambridge University Press. 1979. 1st Paperback edition 2010. ISBN 978-0-521-14250-2.

- Beckwith, Christopher. (1987). The Tibetan Empire in Central Asia. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-05494-0.

- Bernard, P. (1994). "The Greek Kingdoms of Central Asia". In Harmatta, János. History of civilizations of Central Asia, Volume II. The development of sedentary and nomadic civilizations: 700 B.C. to A.D. 250. Paris: UNESCO. pp. 96–126. ISBN 92-3-102846-4.

- Bailey, H.W. (1996) "Khotanese Saka Literature", in Ehsan Yarshater (ed), The Cambridge History of Iran, Vol III: The Seleucid, Parthian, and Sasanian Periods, Part 2 (reprint edition), Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Chang, Chun-shu. (2007). The Rise of the Chinese Empire: Volume II; Frontier, Immigration, & Empire in Han China, 130 B.C. – A.D. 157. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, ISBN 978-0-472-11534-1.

- Davis-Kimball, Jeannine. 2002. Warrior Women: An Archaeologist's Search for History's Hidden Heroines. Warner Books, New York. 1st Trade printing, 2003. ISBN 0-446-67983-6 (pbk).

- Di Cosmo, Nicola. (2002). Ancient China and Its Enemies: The Rise of Nomadic Power in East Asian History. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-77064-4.

- Bulletin of the Asia Institute: The Archaeology and Art of Central Asia. Studies From the Former Soviet Union. New Series. Edited by B. A. Litvinskii and Carol Altman Bromberg. Translation directed by Mary Fleming Zirin. Vol. 8, (1994), pp. 37–46.

- Emmerick, R. E. (2003) "Iranian Settlement East of the Pamirs", in Ehsan Yarshater (ed), The Cambridge History of Iran, Vol III: The Seleucid, Parthian, and Sasanian Periods, Part 1 (reprint edition) Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp 265–266.

- Hill, John E. (2009) Through the Jade Gate to Rome: A Study of the Silk Routes during the Later Han Dynasty, 1st to 2nd Centuries CE. John E. Hill. BookSurge, Charleston, South Carolina. ISBN 978-1-4392-2134-1.

- Hill, John E. 2004. The Peoples of the West from the Weilue 魏略 by Yu Huan 魚豢: A Third Century Chinese Account Composed between 239 and 265 CE. Draft annotated English translation.

- Kuz'mina, Elena E. (2007). The Origin of the Indo Iranians. Edited by J.P. Mallory. Leiden, Boston: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-16054-5.

- Lebedynsky, Iaroslav. (2006). Les Saces: Les <<Scythes>> d'Asie, VIIIe av. J.-C.-IVe siècle apr. J.-C. Editions Errance, Paris. ISBN 2-87772-337-2 (in French).

- Loewe, Michael. (1986). "The Former Han Dynasty," in The Cambridge History of China: Volume I: the Ch'in and Han Empires, 221 B.C. – A.D. 220, 103–222. Edited by Denis Twitchett and Michael Loewe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-24327-8.

- Millward, James A. (2007). Eurasian Crossroads: A History of Xinjiang (illustrated ed.). Columbia University Press. ISBN 0231139241.

- Pulleyblank, Edwin G. 1970. "The Wu-sun and Sakas and the Yüeh-chih Migration." Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies 33 (1970), pp. 154–160.

- Puri, B. N. 1994. "The Sakas and Indo-Parthians." In: History of civilizations of Central Asia, Volume II. The development of sedentary and nomadic civilizations: 700 B.C. to A.D. 250. Harmatta, János, ed., 1994. Paris: UNESCO Publishing, pp. 191–207.

- Sulimirski, Tadeusz (1970). The Sarmatians. Volume 73 of Ancient peoples and places. New York: Praeger. pp. 113–114. "The evidence of both the ancient authors and the archaeological remains point to a massive migration of Sacian (Sakas)/Massagetan tribes from the Syr Daria Delta (Central Asia) by the middle of the second century B.C. Some of the Syr Darian tribes; they also invaded North India."

- Theobald, Ulrich. (26 November 2011). "Chinese History - Sai 塞 The Saka People or Soghdians." ChinaKnowledge.de. Accessed 2 September 2016.

- Thomas, F. W. 1906. "Sakastana." Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society (1906), pp. 181–216.

- Torday, Laszlo. (1997). Mounted Archers: The Beginnings of Central Asian History. Durham: The Durham Academic Press, ISBN 978-1-900838-03-0.

- Tremblay, Xavier (2007), "The Spread of Buddhism in Serindia: Buddhism Among Iranians, Tocharians and Turks before the 13th Century", in The Spread of Buddhism, eds Ann Heirman and Stephan Peter Bumbacker, Leiden: Koninklijke Brill.

- Xue, Zongzheng (薛宗正). (1992). History of the Turks (突厥史). Beijing: Zhongguo shehui kexue chubanshe. ISBN 978-7-5004-0432-3; OCLC 28622013.

- Yu, Taishan. 1998. A Study of Saka History. Sino-Platonic Papers No. 80. July, 1998. Dept. of Asian and Middle Eastern Studies, University of Pennsylvania.

- Yu, Taishan. 2000. A Hypothesis about the Source of the Sai Tribes. Sino-Platonic Papers No. 106. September, 2000. Dept. of Asian and Middle Eastern Studies, University of Pennsylvania.

- Yu, Taishan (June 2010), "The Earliest Tocharians in China" in Victor H. Mair (ed), Sino-Platonic Papers, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, University of Pennsylvania Department of East Asian Languages and Civilizations.

- Yü, Ying-shih. (1986). "Han Foreign Relations," in The Cambridge History of China: Volume I: the Ch'in and Han Empires, 221 B.C. – A.D. 220, 377-462. Edited by Denis Twitchett and Michael Loewe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-24327-8.

- Wechsler, Howard J.; Twitchett, Dennis C. (1979). Denis C. Twitchett; John K. Fairbank, eds. The Cambridge History of China, Volume 3: Sui and T'ang China, 589–906, Part I. Cambridge University Press. pp. 225–227. ISBN 978-0-521-21446-9.

- West, Barbara A. (January 1, 2009). Encyclopedia of the Peoples of Asia and Oceania. Infobase Publishing. ISBN 1438119135. Retrieved January 18, 2015.

External links

- Scythians/Sacae by Jona Lendering

- Article by Kivisild et al. on genetic heritage of early Indian settlers

- Indian, Japanese and Chinese Emperors