Settle–Carlisle line

| Settle–Carlisle line | |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Overview | |

| Type | Main line |

| System | National Rail |

| Status | Operational |

| Locale |

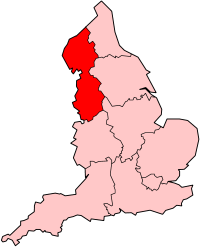

North West England Yorkshire and the Humber |

| Termini |

Settle 54°04′01″N 2°16′51″W / 54.0669°N 2.2807°W Carlisle 54°53′28″N 2°56′01″W / 54.8911°N 2.9335°W |

| Stations | 10 |

| Services | 1 |

| Operation | |

| Opened | 1875 (goods) and 1876 (passengers) |

| Owner | Network Rail |

| Operator(s) | Northern Rail |

| Depot(s) | Neville Hill, Leeds |

| Rolling stock | Primarily Class 158 |

| Technical | |

| Line length | 71.75 mi (115.47 km) |

| Number of tracks | Double |

| Track gauge | Standard gauge 4 ft 8 1⁄2 in (1,435 mm) |

| Operating speed | 60 mph |

| Highest elevation | Ais Gill (1,169 feet (356 m)) |

| Settle–Carlisle line | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Settle–Carlisle line (also known as the Settle and Carlisle (S&C)) is a 73-mile-long (117 km) main railway line in northern England. The route, which crosses the remote, scenic regions of the Yorkshire Dales and the North Pennines, runs between Settle Junction on the Leeds to Morecambe line and Carlisle near the English-Scottish borders. The historic line was constructed in the 1870s and has several notable tunnels and viaducts such as the imposing Ribblehead.

The line is a part of the National Rail network that is managed by Network Rail. All passenger services are operated by Northern apart from those temporary diverted services (due to closures of the West Coast Main Line). Stations serve towns such as Settle in North Yorkshire and Appleby-in-Westmorland in Cumbria as well as small rural communities along its route.

In the 1980s, the Settle-Carlisle was scheduled for closure by British Rail. This prompted rail groups, enthusiasts, local authorities and residents along the route to fight a successful campaign to save the railway. In 1989 the UK government announced it had declined to close the line. Since then passenger numbers have grown steadily to 1.2 million in 2012. Eight formerly closed stations have also been reopened. Several quarries have also been reconnected to the line. It remains one of the most popular railway routes in the UK for charter trains and specials. After damage by a landslip, part of the line was closed from February 2016 to March 2017. To celebrate the reopening, the first regular mainline scheduled service in England for more than half a century ran with a steam engine.

History

Background

The S&C had its origins in railway politics; the expansion-minded Midland Railway company was locked in dispute with the rival London and North Western Railway over access rights to the latter’s tracks to Scotland.

The Midland's access to Scotland was via the "Little North Western" route to Ingleton. The Ingleton branch line from Ingleton to Low Gill, where it joined the Lancaster and Carlisle Railway, was under the control of the rival LNWR. Initially the routes, although physically connected at Ingleton, were not logically connected, as the LNWR and Midland could not agree on sharing the use of Ingleton station. Instead the LNWR terminated its trains at its own station at the end of Ingleton Viaduct, and Midland Railway passengers had to change into LNWR trains by means of a walk of about a mile over steep gradients between the two stations.[5]

An agreement was reached over station access, enabling the Midland to attach through carriages to LNWR trains at Ingleton. Passengers could continue their journey north without leaving the train. The situation was not ideal, as the LNWR handled the through carriages of its rival with deliberate obstructiveness, for example attaching the coaches to slow goods trains instead of fast passenger workings.[6][7]

The route through Ingleton is closed, but the major structures, Low Gill and Ingleton viaducts, remain. It was a well-engineered line suitable for express passenger running, however its potential was never realised due to the rivalry between the companies. The Midland board decided that the only solution was a separate route to Scotland. Surveying began in 1865, and in June 1866, Parliamentary approval was given to the Midland’s plan. Soon after, the Overend-Gurney banking failure sparked a financial crisis in the UK. Interest rates rose sharply, several railways went bankrupt and the Midland's board, prompted by a shareholders' revolt, began to have second thoughts about a venture where the estimated cost was £2.3 million (equivalent to £190 million in 2015).[8] As a result, in April 1869, with no work started, the company petitioned Parliament to abandon the scheme it had earlier fought for. However Parliament, under pressure from other railways which would benefit from the scheme that would cost them nothing, refused, and construction commenced in November that year.

As this date falls between the publication of the 1st Edition 1:2500 Ordnance Survey map and its 1st Revision, the impact of construction can be observed by studying those maps.

Construction

The line was built by over 6,000 navvies,[9] who worked in remote locations, enduring harsh weather conditions. Large camps were established to house the navvies, most of them Irish, with many becoming complete townships with post offices and schools. They were named Inkerman, Sebastapol and Jericho. The remains of one camp—Batty Green—where over 2,000 navvies lived and worked, can be seen near Ribblehead. The Midland Railway helped pay for scripture readers to counteract the effect of drunken violence in these isolated communities.

A plaque in the church at Chapel-le-Dale records the workers who died—both from disease and accidents—building the railway. The death toll is unknown but 80 people died at Batty Green alone following a smallpox epidemic.[9]

A memorial stone was laid in 1997 in the churchyard of St Mary's Church, Mallerstang to commemorate the 25 railway builders and their families who died during the construction of this section of the line, and who were buried there in unmarked graves.

The engineer for the project was John Crossley from Leicestershire, a veteran of other Midland schemes. The terrain traversed is among the bleakest and wildest in England, and construction was halted for months at a time due to frozen ground, snowdrifts and flooding. One contractor had to give up as a result of underestimating the terrain and the weather—Dent Head has almost four times the rainfall of London. Another long-established partnership dissolved under the strain; that of Eckersley and Bayliss. They were contracted to construct the 23 mi (37 km) section from Kirkby Thore to Petteril Bridge in Carlisle.[10]

The line was engineered to express standards throughout—local traffic was secondary and many stations were miles from the villages they purported to serve. The railway's summit at 1,169 feet (356 m) is at Ais Gill, north of Garsdale. To keep the gradients to less than 1 in 100 (1%), a requirement for fast running using steam traction, huge engineering works were required. Even so, the terrain imposed a 16-mile (26 km) climb from Settle to Blea Moor, almost all of it at 1 in 100, and known to enginemen as ‘the long drag’.

The line required 14 tunnels and 22 viaducts, the most notable is the 24 arch Ribblehead Viaduct which is 104 ft (32 m) high and 440 yards (402 m) long. The swampy ground meant that the piers had to be sunk 25 ft (8 m) below the peat and set in concrete in order to provide a suitable foundation. Soon after crossing the viaduct, the line enters Blea Moor tunnel, 2,629 yd (2,404 m) long and 500 ft (152 m) below the moor, before emerging onto Dent Head Viaduct. The summit at Aisgill is the highest point reached by main line trains in England. The tunnel at Lazonby was constructed at the request of a local vicar as he did not want the railway to run past the vicarage.[11]

Water troughs were laid between the tracks at Garsdale enabling steam engines to take water without losing speed.

The remains of the navvies' camp at Rise Hill tunnel were investigated by Channel 4's Time Team in 2008, for a programme that was broadcast on 1 February 2009.

Operation

The line opened for goods traffic in August 1875 with the first passenger trains starting in April 1876. The cost of the line was £3.6 million (equivalent to £310 million in 2015)[8] – 50 per cent above the estimate and a colossal sum for the time.

For some time the Midland dominated the market for London-Glasgow traffic, providing more daytime trains than its rival. In 1923 The Midland was merged into the London Midland & Scottish Railway, with the LNWR also forming part of the new company. In the new company, the disadvantages of the Midland’s route were clear – its steeper gradients and greater length meant it could not compete on speed from London to Glasgow, especially as Midland route trains had to make more stops to serve major cities in the Midlands and Yorkshire. The Midland had long competed on the extra comfort it provided for its passengers but this advantage was lost in the merged company.

After nationalisation in 1948, the pace of rundown quickened. It was regarded as a duplicate line, and control over the through London-Glasgow route was split over several regions which made it hard to plan popular through services. Mining subsidence affected speeds through the East Midlands and Yorkshire. In 1962, the Thames–Clyde Express travelling via the S&C took almost nine hours from London to Glasgow – over the West Coast Main Line the journey length was 7 hours 20 minutes.

In the 1963, Beeching Report into the restructuring of British Rail recommended the withdrawal of all passenger services from the line. Some smaller stations had closed in the 1950s. Although the Beeching recommendations were shelved, it is clear that closure of the line was planned as early as the late 1960s. Such closure is referred to in paragraph 40 of the official report into the accident involving two Northbound class 40 hauled goods trains, between Horton In Ribblesdale and Selside on 30 October 1968, by Lt. Colonel I.K.A. McNaughton:

"... Even if the Settle and Carlisle line were planned to form part of the long term railway network of the country, it would still come fairly low in the priority list for installation of AWS; this route, however, is planned for closure within the next few years ..."

In May 1970 all stations except for Settle and Appleby West were closed, and its passenger service cut to two trains a day in each direction, leaving mostly freight.

Few express passenger services continued to operate, The Waverley from London St Pancras to Edinburgh Waverley via Nottingham ended in 1968, while the Thames–Clyde Express from London to Glasgow Central via Leicester, lasted until 1975. Night sleepers from London to Glasgow continued until 1976. After that a residual service from Glasgow – cut back at Nottingham (three trains each way) – survived until May 1982.

Threat of closure

During the 1970s, the S&C suffered from a lack of investment, and most freight traffic was diverted onto the electrified West Coast Main Line. The condition of many viaducts and tunnels deteriorated due to lack of investment. Dalesrail began operating services to closed stations on summer weekends in 1974. These were promoted by the Yorkshire Dales National Park Authority to encourage ramblers.

In the early 1980s, the S&C was carrying only a handful of trains per day, and British Rail decided the cost of renewing the viaducts and tunnels would be prohibitively expensive, given the small amount of traffic carried on the line. In 1981 a protest group, the Friends of the Settle–Carlisle Line (FoSCL), was established, and campaigned against the line's closure even before it was officially announced.

In 1984, closure notices were posted at the S&C's remaining stations. However, local authorities and rail enthusiasts joined together and campaigned to save the S&C, pointing out that British Rail was ignoring the S&C's potential for tourism, ignoring the need for a diversionary route to the West Coast main line, and failing to promote through traffic from the Midlands and Yorkshire to Scotland.

There was outrage over the closure plan: critics pointed out that this was a main line, not a small branch railway. The campaign uncovered evidence that British Rail had mounted a dirty tricks campaign against the line,[12] exaggerating the cost of repairs (£6 million for Ribblehead Viaduct alone)[13] and diverting traffic away from the line in order to justify its closure plans, a process referred to as closure by stealth.[14]

Publicity over British Rail's tactics succeeded in a huge increase in traffic. Journeys per year were 93,000 in 1983 when the campaign began, 450,000 by 1989. As late as August 1988, the British Rail Board posted adverts stating they had appointed Lazard Brothers to 'advise on the sale of the Settle–Carlisle line'.[15] As a result of the successful campaign, the government finally refused consent to close the line in 1989, and British Rail started to repair the deteriorating tunnels and viaducts.[16]

Statue of Ruswarp

In 2009 a statue of the border collie Ruswarp (pronounced Russup), was sited on the platform of the refurbished Garsdale railway station.[17] The commemorative sculpture, funded by public subscription, was made by sculptor Joel Walker and cast in bronze. It celebrates the saving of the railway line which was coordinated by the Friends of the Settle to Carlisle Line, whose first secretary, Graham Nuttall, was a keen hillwalker; his dog Ruswarp signed the petition to save the line with his paw print.[18] On 20 January 1990 Graham Nuttall went missing. He and Ruswarp had bought day return tickets from Burnley to Llandrindod Wells to go walking in the Welsh Mountains, but they never returned. Searches in the Elan Valley and Rhayader found nothing until on 7 April 1990, a lone walker found Nuttall's body beside a stream. The 14-year-old Ruswarp was nearby, having stayed by his master's body for 11 weeks in winter weather; he was so weak that he had to be carried down the mountain. His veterinary fees were paid by the RSPCA, who awarded him their Animal Medallion and collar for 'vigilance' and Animal Plaque for 'intelligence and courage'. He died shortly after Nuttall's funeral.[17]

Current situation

In recent years, due to congestion on the West Coast Main Line, much rail-freight traffic is using the S&C once again. Coal from the Hunterston coal terminal in Scotland is carried to power stations in Yorkshire, and Gypsum is transported from Drax Power Station to Kirkby Thore. Major engineering work was needed to upgrade the line to the standards required for such heavy freight traffic and additional investment made to reduce the length of signal sections. In July 2009 work to stabilise a length of embankment near Kirkby Thore and remove a long-standing permanent speed restriction was undertaken.[19] More recently the line has experienced an upturn in fortunes. Eight formerly closed stations have reopened and passenger levels have increased significantly since the 1980s, with 1.2 million passengers recorded in 2012.[20] Ribblehead station features a special visitor centre. The line is an important diversionary route from the electrified West Coast Main Line during engineering works. However, as the line is not electrified, electric trains such as Pendolinos need to be hauled by diesel locomotives (typically a Class 57 Thunderbird) along the diversion section.

Anglo-Scottish expresses have not been fully restored. The former regional franchisee Arriva Trains Northern initiated a twice daily Leeds–Glasgow Central service in 1999 (calling at Settle, Appleby, Carlisle, Lockerbie and Motherwell). The service was withdrawn at the behest of the Strategic Rail Authority in 2003,[21] and there remains no link from Yorkshire or the East Midlands to Glasgow over the line. The link from Lancashire operates on Sundays during the summer months for the benefit of ramblers under the DalesRail brand.[22]

In April 2014, the 25th anniversary of the line's reprieve was celebrated by the running of a special train from Leeds to Carlisle over the route. This conveyed many of the campaigners who fought to save the line and called at Settle station, where a ceremony was held to commemorate the announcement made on 11 April 1989 that the line would be kept open. Michael Portillo, the Transport Secretary in the Thatcher government of the time (and who made the official announcement regarding the line in parliament) attended the celebrations.[23][24][25]

Reconnection to quarries

In July 2015 it was announced that the stone quarries at Arcow and Dry Rigg would be reconnected to the line via north facing points. Stone from both of these quarries is in demand for road building due to its high PSV (Polished Stone Value) and would be taken out of the Yorkshire Dales National Park by freight train instead of lorries.[26][27] The work was undertaken during the last quarter of 2015 with the link opening to traffic in 2016.[28][29]

New Northern franchise

In December 2015, it was announced that Arriva Rail North Ltd had been awarded the rights to operate the new Northern Rail franchise from April 2016 (replacing current franchisees Serco & Abellio)[30] As part of the new franchise agreement with the DfT, the new operator will run one additional return journey over the line on weekdays (leaving Leeds in the late afternoon and returning from Carlisle later in the evening than the current last train) and two extra services each way on Sundays.

2015–16 temporary closures

The winter of 2015–16 saw services over the route repeatedly disrupted by flooding and a serious landslip north of Armathwaite. Storm Desmond saw the line closed for several days at the beginning of December by flooding at several different locations, whilst the landslip at Eden Brows near Armathwaite resulted in the closure of the southbound line between Cumwhinton and Culgaith from 29 January 2016 to allow the damaged embankment to be inspected and stabilised. Problems had first been reported in mid-December 2015, but repairs were carried out and services resumed on 22 December.[31] Single line working was in place for several days over the northbound line whilst the remedial work continued and an emergency timetable was in operation.[32] Further ground movement at the site (due to the base of the embankment being eroded by the river and the saturated nature of the fill material originally used to construct the embankment) led to the complete closure of the line between Appleby & Carlisle on 9 February 2016, with buses replacing trains over this section. [33] Repairs to the affected section entailed building a 100m-long piled retaining wall and support platform for the track and stabilising the embankment beneath it; work began in July 2016 and was completed in March 2017.[34] The line between Appleby and Armathwaite was reopened to traffic on 27 June 2016 on a temporary timetable;[35] the repair project was estimated to cost £23 million.[36] In February 2017, to celebrate the forthcoming reopening of the line on 31 March, scheduled trains drawn by 60163 Tornado ran in February, the first regular mainline scheduled service in England using steam for more than half a century.[37][38] The service carried more than 5,500 passengers during its three days of operation.[39]

Work on the piled wall and trackbed at Eden Brows was completed and the work site was handed back to Network Rail on 22 March 2017, allowing the infrastructure operator to recommission and fully test the track and signalling system over the affected section of line ahead of the scheduled reopening date. The Flying Scotsman operated a special trip to Carlisle and back to celebrate the full opening to traffic on 31 March.

Rolling stock

Passenger services are usually operated by Class 158 DMUs, although Class 153 and Class 156 units can also be used (the former to add additional capacity on certain services and the latter on the seasonal DalesRail trains from Preston and Blackpool). Class 142 and Class 144 units can make occasional appearances on the route, but only as short-notice replacements for the booked units or on transfer moves between depots. Class 150 units have also begun to appear occasionally[40] (as substitutes for the booked 158s) since a batch of the units were transferred to Northern Rail from London Midland in the autumn of 2011.

Route

- Settle Junction – the start of the line. Site of the junction with the Leeds to Morecambe Line and a short-lived (1876–77) passenger station.

- Settle

- Taitlands Tunnel (now called Stainforth Tunnel)

- Horton in Ribblesdale

- Ribblehead- here is the Ribblehead Viaduct (originally named Batty Moss Viaduct) 440 yd (396 m), with 24 piers

- Blea Moor here is Blea Moor signal box and loop. Blea Moor signalbox is the remotest signal box in England[41]

- Blea Moor Tunnel 2629 yd (2366 m) long

- here are the Dent Head & Arten Gill viaducts.

- Dent (4.5 miles outside the village of Dent)

- Rise Hill Tunnel

- here were the highest water troughs in the United Kingdom. Steam locomotives were able to pick up water from these troughs whilst still moving.

- Dent is the highest railway station in England.

- Garsdale – originally named Hawes Junction then Hawes Junction & Garsdale.

- At Hawes station, on the Hawes branch to the east of the main line, there was an end-on-junction with the North Eastern Railway (NER) line across the Pennines to Northallerton (now the Wensleydale Railway).

- On the next stretch, there were three tunnels (Moorcock Tunnel, Shotlock Hill Tunnel and Birkett Tunnel).

- On this stretch also was the summit of the line at Ais Gill, 1169 ft (350 m) ASL. From 1954, the summit was marked by a vitreous enamel sign.[42]

Ais Gill summit notice board in 2017 painted in quasi Midland Railway colours

Ais Gill summit notice board in 2017 painted in quasi Midland Railway colours

- Kirkby Stephen - There were two stations here, one (Kirkby Stephen West) for the Midland line and Kirkby Stephen East for the NER (the latter's line from Darlington to Tebay). The two stations are about half a mile apart. The Midland station also served the village of Ravenstonedale

- Crosby Garrett (closed 1952)

- Ormside (closed 1952)

- Appleby – as with Kirkby Stephen, there were separate stations for the Midland (Appleby West) and NE lines (Appleby East), with a siding connection. The NE line was the branch known as the Eden Valley Railway between Kirkby Stephen and Eden Valley Junction on the West Coast Line near Clifton

- Long Marton (closed 1970)

- New Biggin (closed 1970)

- Culgaith (closed 1970)

- there are three tunnels between these stations

- Langwathby

- Little Salkeld (closed 1970)

- here is Lazonby Tunnel

- Lazonby and Kirkoswald

- there are three more tunnels between these two stations

- Armathwaite

- Cotehill (closed 1952)

- Cumwhinton (closed 1956)

- Scotby (closed 1942 – not the same station as the one of the same name on the adjoining Tyne Valley line)

- Petterill Bridge Junction – junction with the Newcastle – Carlisle line and the end of Midland Railway metals.

- Carlisle: the station – full title Carlisle Citadel was owned jointly by the LNWR and the Caledonian Railway: the Midland (among others) was a "tenant Company".

Accidents

- 1910 – Hawes Junction rail crash; 12 killed, 17 injured.

- 1913 – Ais Gill rail accident (1913); 16 killed, 38 injured.

- 1918 – Little Salkeld rail accident; 7 killed.

- 1930 – Culgaith rail accident; 2 killed, 8 injured.

- 1933 – Little Salkeld station collision; 1 killed, 35 injured.[43]

- 1952 – Blea Moor derailment 34 injured.[44]

- 1960 – Settle rail crash; 5 killed, 8 injured.

- 1968 – Horton rail crash; Major damage, no fatalities; 2 injured.[45]

- 1995 – Ais Gill rail accident (1995); 1 killed.

- 1999 – Crosby Garrett rail accident.

Simulators

The line is featured in Microsoft Train Simulator, which depicts the line as it was in the 1920s, 1930s, and 1940s, depicting all of the stations on the line, with the player able to drive the Flying Scotsman or British Rail Class 50 Valiant along the 73-mile (117 km) line.

Trainz Railway Simulator has a Settle & Carlisle package for editions Trainz Classics 3, TS2009, TS2010, TS12, and T:ANE. This is modelled on the line under British Railways ownership in the fading days of steam power in the late 1950s and early 1960s. Locomotives range from the L&YR Class 23s and BR Class 24s to LNER A3 Pacifics and BR Class 40s. Simulator sessions are provided in two versions: ride (all railway operations are performed under AI control) and drive (you take control of one train in the session). The route actually begins at Skipton, rather than Settle, since the latter is a junction. Trainz Railroad Simulator 2006 included a demo version of the route, featuring the mainline from Ais Gills summit to a fictional colliery town called Wharton. Dent, Garsdale and the Hawes branchline were also included.

The Route is available for free download from UKTrainsim for RailWorks Simulator and a payware version from railsimulator.com for Train Simulator 2012 (Railworks 3).

In popular culture

In 1983 a film documentary about the line was released, named 'Steam on the Settle & Carlisle'.[46] In March 2016 a fifty-minute colour documentary "The Long Drag", made in 1962-3 was released for free viewing on the British Film Institute website.

References

- ↑ Baker, S.K. (2007 11th ed), Rail Atlas of Great Britain & Ireland, Oxford Publishing Co, Horsham, ISBN 978 0 86093 602 2

- ↑ Dewick, T. (2002), Complete Atlas of Railway Station Names, Ian Allan Publishing, ISBN 0 7110 2798 6

- ↑ Midland Railway (reprinted after 1992) [originally 1913–1920], Midland Railway System Maps Volume 1: Carlisle to Leeds and Branches, Peter Kay, Teignmouth, ISBN 1 899890 25 4

- ↑ (1990) British Rail Track Diagrams 4: Midland Region, Quail Map Company, Essex, ISBN 0 900609 74 5, p.34

- ↑ "Ingleton Viaduct on". Forgottenrelics.co.uk. 30 January 1954. Retrieved 16 March 2014.

- ↑ "History of the S&C on". Settle-carlisle.co.uk. Retrieved 16 March 2014.

- ↑ Houghton, F.W & Foster W.H (1965 Second Ed) The Story Of The Settle - Carlisle Line, Advertiser Press Ltd, Huddersfield, p.16

- 1 2 UK Consumer Price Index inflation figures are based on data from Gregory Clark (2016), "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)", MeasuringWorth.com.

- 1 2 Wolmar, Christian (2008). Fire and Steam. Atlantic Books. p. 161. ISBN 978-1-84354-630-6.

- ↑ Davies, Peter. "Friends of the Settle Carlisle Line" (PDF). FOSCL. National Archives. p. 9. Retrieved 20 November 2015.

- ↑ Davies, Peter. "Friends of the Settle Carlisle Line" (PDF). FOSCL. National Archives. p. 10. Retrieved 20 November 2015.

- ↑ "History of the Settle Carlisle". Visit Cumbria. Retrieved 12 November 2015.

- ↑ "Battle to prevent the end of the line". Telegraph and Argus. 24 April 2009. Retrieved 12 November 2015.

- ↑ Towler, p.74

- ↑ Rail magazine No. 83 page 25, EMAP National Publications Ltd.

- ↑ "Long Battle to Save Settle – Carlisle Line Ends In Success". Telegraph & Argus. 10 April 1999. Retrieved 29 October 2008.

- 1 2 "Tribute to devoted dog unveiled". BBC Cumbria. BBC. 17 April 2009. Retrieved 12 August 2009.

- ↑ "Statue will honour hero dog Ruswarp". Pendle Today. Johnston Press Digital Publishing. 15 April 2008. Retrieved 12 August 2009.

- ↑ Article & Photos of track repair work at Kirkby Thore in 2009 The Railway Cutting; Retrieved 29 December 2010

- ↑ Stokes, Spencer (15 December 2013). "Settle–Carlisle line thriving 30 years on after closure threat".

- ↑ "SRA Stakeholder Briefing: Northern Rail Franchise". Archived from the original on 11 August 2007. Retrieved 8 February 2009.

... existing ATN operated Leeds–Carlisle service, extended to Glasgow once a day in each direction, will no longer run between Carlisle and Glasgow from September 2003.

- ↑ "DalesRail". Retrieved 8 February 2009.

- ↑ "Settle–Carlisle railway line marks special anniversary". Craven Herald. 10 April 2014. Retrieved 11 April 2014.

- ↑ "How the iconic Settle–Carlisle railway line was saved". BBC News. 10 April 2014. Retrieved 10 April 2014.

- ↑ "Reliving the great day when the Settle–Carlisle line was saved". Craven Herald. 19 April 2014. Retrieved 22 April 2014.

- ↑ White, Clive (16 July 2015). "Railway link to main line will cut lorry traffic on Dales roads". Craven Herald. Retrieved 8 October 2015.

- ↑ "Arcow Quarry Non Technical Summary" (PDF). LaFarge Tarmac. Retrieved 8 October 2015.

- ↑ "Work to reinstate quarry link at Horton-in-Ribblesdale reaches major milestone". Bradford Telegraph and Argus. Retrieved 4 November 2015.

- ↑ http://www.railengineer.uk/2016/01/05/connected/

- ↑ Northern & Trans-Pennine Franchises awarded Railway Gazette article 9 December 2015; Retrieved 9 December 2015

- ↑ Good news for Northern Rail customers after Armathwaite storm damage repairedNetwork Rail Media Centre; Retrieved 1 February 2016

- ↑ Track works and delays north of ApplebyFriends of the Settle–Carlisle Line news article 30 January 2016; Retrieved 1 February 2016

- ↑ "Railway between Carlisle and Appleby to be closed for months after major landslip"Network Rail Media Centre; Retrieved 15 February 2016

- ↑ "Repair solution agreed for Settle to Carlisle railway land slip"Network Rail Media Centre 3 March 2016; Retrieved 10 March 2016

- ↑ Stephen, Paul (28 June 2016). "S&C rail services run to Armathwaite". Rail. Peterborough: Bauer Consumer Media Ltd.

- ↑ £23m landslip repair set to reopen Settle–Carlisle railway line in March 2017Network Rail Media Centre press release 7 July 2016; Retrieved 7 July 2016

- ↑ "Settle-Carlisle line: Tornado powers 12 scheduled services". BBC news. 14 February 2017. Retrieved 14 February 2017.

- ↑ Pidd, Helen (14 February 2017). "Full steam ahead as Tornado engine powers Settle-Carlisle train service". The Guardian. Retrieved 15 February 2017.

- ↑ "First scheduled steam train service used by 5,500 people". BBC NEWS. 19 February 2017.

- ↑ Class 150 DMU 150112 at Carlisle forming the 1550 to Leeds on 11 February 2012 Railway Herald website; Retrieved 13 April 2012

- ↑ Allison, Ian (September 2015). "News View" (PDF). IRSE. 214: 1. Retrieved 17 November 2015.

- ↑ Cooke, B.W.C., ed. (June 1954). "Notes and News". The Railway Magazine. Vol. 100 no. 638. Westminster: Tothill Press. p. 434.

- ↑ Accident at Little Salkeld on 10th July 1933

- ↑ 1952 official accident report

- ↑ Horton 1968 official accident report

- ↑ "History | Settle Carlisle Railway". settle-carlislerailway.co.uk. Retrieved 3 November 2015.

Bibliography

- Abbott, Stan and Whitehouse, Alan (1994) [first published 1990] The line that refused to die. Hawes: Leading Edge. ISBN 0-948135-43-3

- Baughan P E (1966) The Midland Railway North of Leeds

- Houghton F W & Foster W H (1948) The Story of the Settle – Carlisle line.

- Towler J (1990) The Battle for the Settle & Carlisle Platform 5 Publishing, Sheffield ISBN 1-872524-07-9

- Williams F S (1875, reprinted 1968) Williams' Midland Railway

Further reading

- Whitehead, Alan (December 1981 – January 1982). "New worries over Settle–Carlisle". Rail Enthusiast. EMAP National Publications. pp. 10–11. ISSN 0262-561X. OCLC 49957965.

- Whitehouse, Alan (February–March 1982). "New Settle–Carlisle controversy". Rail Enthusiast. EMAP National Publications. p. 47. ISSN 0262-561X. OCLC 49957965.

- Crome, Philip E. (October 1982). "Outlook Bleak!". Rail Enthusiast. EMAP National Publications. pp. 34–37. ISSN 0262-561X. OCLC 49957965.

- Whitehouse, Alan (February 1983). "Dales rail stations cling to life – but for how much longer?". Rail Enthusiast. EMAP National Publications. p. 46. ISSN 0262-561X. OCLC 49957965.

- Fox, Peter (November 1984). "The S&C a suitable case for treatment". Rail Enthusiast. EMAP National Publications. pp. 36–40. ISSN 0262-561X. OCLC 49957965.

- Whitehouse, Alan; Brown, Murray (July 1988). "Settle & Carlisle: Sentence of death or enlightened reprieve?". RAIL. No. 82. EMAP National Publications. pp. 6–7. ISSN 0953-4563. OCLC 49953699.

- "Scenic Settle & Carlisle line enjoys freight boom". RAIL. No. 318. EMAP Apex Publications. 19 November – 2 December 1997. p. 42. ISSN 0953-4563. OCLC 49953699.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Settle to Carlisle Line. |

- Settle–Carlisle Partnership – timetables, online secure shop, route guides and the latest news, plus information about FoSCL

- Friends of the Settle–Carlisle Line (FoSCL) – information, recent news and events, guided walks and membership information

- Friends of DalesRail – Free guided walks from the Settle–Carlisle railway

- A history of the Mallerstang section of the line, and a commemoration of those who died during its construction, and in three accidents in this dale

- Images and information of each railway station

- Report on the attempt to close the line and the campaign to keep it open.

- Time Team: Blood, Sweat and Beers – Rise Hill, Cumbria

- Settle to Carlisle update – February 2016. Network Rail video on the 2016 landslip at Eden Brows

- Eden Brows Landslip – Contractor video on the status of repair works at Eden Brows in July 2016

Coordinates: 54°31′01″N 2°27′22″W / 54.517°N 2.456°W