Senussi

| Senussi dynasty السنوسية (in Arabic) | |

|---|---|

| |

| Country |

|

| Founder | Muhammad ibn Ali as-Senussi |

| Final ruler | Idris of Libya |

| Deposition | 1969: Overthrown by Muammar Gaddafi's 1 September Coup d'état |

| Current head |

Mohammed El Senussi; Idris bin Abdullah al-Senussi (rival claimant) |

| Titles | |

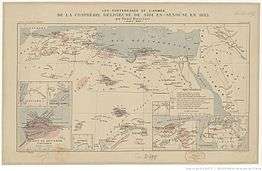

The Senussi or Sanussi (Arabic: السنوسية) are a Muslim political-religious tariqa (Sufi order) and tribe in colonial Libya and the Sudan region founded in Mecca in 1837 by the Grand Senussi (Arabic: السنوسي الكبير), the Algerian Muhammad ibn Ali as-Senussi. Senussi was concerned with what it saw as both the decline of Islamic thought and spirituality and the weakening of Muslim political integrity. From 1902 to 1913 the Senussi fought French colonial expansion in the Sahara and the Kingdom of Italy's colonisation of Libya beginning in 1911. In World War I, they fought the Senussi Campaign against the British in Egypt and Sudan. During World War II, the Senussi tribe provided vital support to the British Eighth Army in North Africa against Nazi German and Fascist Italian forces. The Grand Senussi's grandson became king Idris of Libya in 1951. In 1969, Idris I was overthrown by a military coup led by Muammar Gaddafi.

Beginnings 1787–1859

The Senussi order has been historically closed to Europeans and outsiders, leading reports of their beliefs and practices to vary immensely. Though it is possible to gain some insight from the lives of the Senussi sheikhs further details are difficult to obtain.

Muhammad ibn Ali as-Senussi (1787–1859), the founder of the order and a proponent of Sufism, was born in Algeria near Mostaganem and was named al-Senussi after a venerated Muslim teacher. He was a member of the Walad Sidi Abdalla tribe, and was a sharif tracing his descent from Fatimah, the daughter of Mohammed. He studied at a madrasa in Fez, then traveled in the Sahara preaching a purifying reform of the faith in Tunisia and Tripoli, gaining many adherents, and then moved to Cairo to study at Al-Azhar University. The pious scholar was forceful in his criticism of the Egyptian ulama for what he perceived as their timid compliance with the Ottoman authorities and their spiritual conservatism. He also argued that learned Muslims should not blindly follow the four classical madhhabs (schools of law) but instead engage in ijtihad themselves. Not surprisingly, he was opposed by the ulama as unorthodox and they issued a fatwa against him.

Senussi went to Mecca, where he joined Ahmad ibn Idris al-Fasi, the head of the Khadirites, a religious fraternity of Moroccan origin. On the death of al-Fasi, Senussi became head of one of the two branches into which the Khadirites divided, and in 1835 he founded his first monastery or zawiya, at Abu Qubays near Mecca. Due to Wahhabi pressure Senussi left Mecca and settled in Cyrenaica, Libya in 1843, where in the mountains near Sidi Rafaa' (Bayda) he built the Zawiya Bayda ("White Monastery"). There he was supported by the local tribes and the Sultan of Wadai and his connections extended across the Maghreb.

The Grand Senussi did not tolerate fanaticism and forbade the use of stimulants as well as voluntary poverty. Lodge members were to eat and dress within the limits of Islamic law and, instead of depending on charity, were required to earn their living through work. He accepted neither the wholly intuitive ways described by some Sufi mystics nor the rationality of some of the orthodox ulama; rather, he attempted to achieve a middle path. The Bedouin tribes had shown no interest in the ecstatic practices of the Sufis that were gaining adherents in the towns, but they were attracted in great numbers to the Senussis. The relative austerity of the Senussi message was particularly suited to the character of the Cyrenaican Bedouins, whose way of life had not changed much in the centuries since the Arabs had first accepted the Prophet Mohammad's teachings.[1]

In 1855 Senussi moved farther from direct Ottoman surveillance to Jaghbub, a small oasis some 30 miles northwest of Siwa. He died in 1860, leaving two sons, Mahommed Sherif (1844–95) and Mohammed al-Mahdi, who succeeded him.

Developments since 1859

Sayyid Muhammad al-Mahdi bin Sayyid Muhammad as-Senussi (1845 – 30 May 1902) was fourteen when his father died, after which he was placed under the care of his father's friends.

The successors to the sultan of the Abu Qubays, Sultan Ali (1858–74) and the Sultan Yusef (1874–98), continued to support the Senussi. Under al-Mahdi the zawiyas of the order extended to Fez, Damascus, Constantinople and India. In the Hejaz members of the order were numerous. In most of these countries the Senussites wielded no more political power than other Muslim fraternities, but in the eastern Sahara and central Sudan things were different. Mohammed al-Mahdi had the authority of a sovereign in a vast but almost empty desert. The string of oases leading from Siwa to Kufra, and Borkou were cultivated by the Senussites and trade with Tripoli and Benghazi was encouraged.

Although named "al-Mahdi" by his father, Muhammad never claimed to be the actual Mahdi (Saviour), although he was regarded as such by some of his followers. When Muhammad Ahmad proclaimed himself the actual Mahdi in 1881, Muhammad Idris decided to have nothing to do with him. Although Muhammad Ahmed wrote twice asking him to become one of his four great caliphs (leaders), he received no reply. In 1890, the Ansar (forces of Muhammad Ahmad al-Mahdi) advancing from Darfur were stopped on the frontier of the Wadai Empire, Sultan Yusuf proving firm in his adherence to the Senussi teachings.

Muhammed al-Mahdi's growing fame made the Ottoman regime uneasy and drew unwelcome attention. In most of Tripoli and Benghazi his authority was greater than that of the Ottoman governors. In 1889 the sheik was visited at Jaghbub by the pasha of Benghazi accompanied by Ottoman troops. This event showed the sheik the possibility of danger and led him to move his headquarters to Jof in the oases of Kufra in 1894, a place sufficiently remote to secure him from a sudden attack.

By this time a new danger to Senussi territories had arisen from the French colonial empire, who were advancing from the French Congo towards the western and southern borders the Wadai Empire. The Senussi kept them from advancing north of Chad.

Leadership of Ahmed Sharif as-Senussi

In 1902, Muhammad Idris died and was succeeded by his nephew, Ahmed Sharif as-Senussi, but his adherents in the deserts bordering Egypt maintained for years that Muhammad was not actually dead. The new head of the Senussi maintained the friendly relations of his predecessors with the Wadai Empire, governing the order as regent for his young cousin, Muhammad Idris II (the future king Idris of Libya), who signed the 1917 Treaty of Acroma that ceded control of Libya from the Kingdom of Italy[2] and was later recognized by them as Emir of Cyrenaica[3] on October 25, 1920.

The Senussi, encouraged by the German and Ottoman Empires, played a minor part in the World War I, utilising guerrilla warfare against the Italian colonials in Libya and the British in Egypt from November 1915 until February 1917, led by Sayyid Ahmad, and in the Sudan from March to December 1916, led by Ali Dinar, the Sultan of Darfur.[4][5] In 1916, the British sent an expeditionary force against them known as the Senussi Campaign led by Major General William Peyton.[6] According to Wavell and McGuirk, Western Force was first led by General Wallace and later by General Hodgson.[7][8]

Italy took Libya from the Ottomans in the Italo-Turkish War of 1911. In 1922, Italian Fascist leader Benito Mussolini launched his infamous Riconquista of Libya — the Roman Empire having done the original conquering 2000 years before. The Senussi led the resistance and Italians closed Senussi khanqahs, arrested sheikhs, and confiscated mosques and their land. Libyans fought the Italians until 1943, with 250-300,000 of them dying in the process.[9]

Chiefs of the Senussi Order

- Muhammad ibn Ali as-Senussi (1843–1859)

- Muhammad al-Mahdi as-Senussi (1859–1902)

- Ahmed Sharif as-Senussi (1902–1916; died 1933)

- Idris of Libya (1916–1969; died 1983)

- Hasan as-Senussi (1969–1992)

- Mohammed El Senussi (1992–present)

Senussi family tree

| many generations go by | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ali ibn Abi Talib | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hasan ibn Ali | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Abdullah bin Hasan | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Idris bin Abdullah | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Muhammad ibn Ali as-Senussi | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Muhammad as-Sharif as-Senussi | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Muhammad al-Mahdi bin Muhammad as-Senussi | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ahmed as-Sharif as-Senussi | Muhammad al-Abid as-Senussi | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Muhammad ar-Reda | Idris I of Libya | Queen Fatima as-Sharif | az-Zubayr bin Ahmad as-Sharif | Abdullah bin Muhammad al- Abid as-Senussi | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hasan as-Senussi | Ahmed as-Senussi (member of NTC) | Idris bin Abdullah as-Senussi (claimant) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mohammed as-Senussi | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

See also

- Senussi Campaign in World War I

- Ahmad ibn Idris al-Fasi

- Idris bin Abdullah al-Senussi

- Ahmed al-Senussi

- Abdullah Senussi

- Omar Mukhtar

- Charles de Foucauld

Sources

- E. E. Evans-Pritchard, The Sanusi of Cyrenaica (1949, repr. 1963)

- N. A. Ziadeh, Sanusiyah (1958, repr. 1983).

- Bianci, Steven, ''Libya: Current Issues and Historical Background New York: Nova Science Publishers, INc, 2003

- L. Rinn, Marabouts et Khouan, a good historical account up to the year 1884

- 0. Depont and X. Coppolani, Les Confrèries religieuses musulmanes (Algiers, 1897)

- Si Mohammed el Hechaish, Chez les Senoussia et les Touareg, in "L'Expansion cot. française" for 1900 and the "Revue de Paris" for 1901. These are translations from the Arabic of an educated Mahommedan who visited the chief Senussite centres. An obituary notice of Senussi el Mahdi by the same writer appeared in the Arab journal El Iladira of Tunis, Sept. 2, 1902; a condensation of this article appears in the "Bull. du Corn. de l'Afriue française" for 5902; Les Senoussia, an anonymous contribution to the April supplement of the same volume, is a judicious summary of events, a short bibliography being added; Capt. Julien, in "Le Dar Ouadai" published in the same Bulletin (vol. for 1904), traces the connection between Wadai and the Senussi

- L. G. Binger, in Le Peril de l'Islam in the 1906 volume of the Bulletin, discusses the position and prospects of the Senussite and other Islamic sects in North Africa. Von Grunau, in "Verhandlungen der Gesellschaft für Erdkunde" for 1899, gives an account of his visit to Siwa

- M.G.E. Bowman–Manifold, An Outline of the Egyptian and Palestine Campaigns, 1914 to 1918 2nd Edition (Chatham: The Institution of Royal Engineers, W. & J. Mackay & Co Ltd, 1923)

- Russell McGuirk The Sanusi's Little War The Amazing Story of a Forgotten Conflict in the Western Desert, 1915–1917 (London, Arabian Publishing: 2007)

- Field Marshal Earl Wavell, The Palestine Campaigns 3rd Edition thirteenth Printing; Series: A Short History of the British Army 4th Edition by Major E.W. Sheppard (London: Constable & Co., 1968)

- Sir F. R. Wingate, in Mahdiism and the Egyptian Sudan (London, 1891), narrates the efforts made by the Mahdi Mahommed Ahmed to obtain the support of the Senussi

- Sir W. Wallace, in his report to the Colonial Office on Northern Nigeria for 1906-1907, deals with Senussiism in that country.

- H. Duveyrier, La Confrèrie musulmane de Sidi Mohammed ben Au es Senoussi (Paris, 1884), a book containing much exaggeration, and A. Silva White, From Sphinx to Oracle (London, 1898), which, while repeating the extreme views of Duveyrier, contains useful information.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "article name needed". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "article name needed". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Notes

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Senussi dynasty. |

- ↑ Metz, Helen Chapin. "The Sanusi Order". Libya: A Country Study. GPO for the Library of Congress. Retrieved 28 February 2011.

- ↑ A. Del Boca, "Gli Italiani in Libia - Tripoli Bel Suol d'Amore" Mondadori 1993, pp. 334-341

- ↑ A. Del Boca, "Gli Italiani in Libia - Tripoli Bel Suol d'Amore" Mondadori 1993, p. 415

- ↑ Field Marshal Earl Wavell, The Palestine Campaigns 3rd Edition thirteenth Printing; Series: A Short History of the British Army 4th Edition by Major E.W. Sheppard (London: Constable & Co., 1968) pp. 35–6

- ↑ M.G.E. Bowman–Manifold, An Outline of the Egyptian and Palestine Campaigns, 1914 to 1918 2nd Edition (Chatham: The Institution of Royal Engineers, W. & J. Mackay & Co Ltd, 1923), p. 23.

- ↑ William Eliot Peyton Centre for First World War Studies. Accessed 19 January 2008.

- ↑ Wavell pp. 37–8.

- ↑ Russell McGuirk The Sanusi's Little War: The Amazing Story of a Forgotten Conflict in the Western Desert, 1915–1917 (London: Arabian Publishing, 2007) pp. 263–4.

- ↑ John L. Wright, Libya, a Modern History, Johns Hopkins University Press, p. 42.