Visual field

The visual field is the "spatial array of visual sensations available to observation in introspectionist psychological experiments".[1]

The equivalent concept for optical instruments and sensors is the field of view (FOV).

In optometry, ophthalmology, and neurology, a visual field test is used to determine whether the visual field is affected by diseases that cause local scotoma or a more extensive loss of vision or a reduction in sensitivity (increase in threshold).

Normal limits

The normal (monocular) human visual field extends to approximately 60 degrees nasally (toward the nose, or inward) from the vertical meridian in each eye, to 107 degrees temporally (away from the nose, or outwards) from the vertical meridian, and approximately 70 degrees above and 80 below the horizontal meridian.[2][3][4][5]

The binocular visual field is the superimposition of the two monocular fields. In the binocular field, the area left of the vertical meridian is referred to as the left visual field (which is temporally for the left, and nasally for the right eye); a corresponding definition holds for the right visual field. The four areas delimited by the vertical and horizontal meridian are referred to as upper/lower left/right quadrants. In the United Kingdom, the minimum field requirement for driving is 60 degrees either side of the vertical meridian, and 20 degrees above and below horizontal. The macula corresponds to the central 17 degrees diameter of the visual field; the fovea to the central 5.2 degrees, and the foveola to 1–1.2 degrees diameter.[6][7]

Measuring the visual field

The visual field is measured by perimetry. This may be kinetic, where spots of light are shown on the white interior of a half sphere and slowly moved inwards until the observer sees them, or static, where the light spots are flashed at varying intensities at fixed locations in the sphere until detected by the subject. Commonly used perimeters are the automated Humphrey Field Analyzer, the Heidelberg Edge Perimeter, or the Oculus.

Another method is to use a campimeter, a small device with a flat screen designed to measure the central visual field.

Light spot patterns testing the central 24 degrees or 30 degrees of the visual field, are most commonly used. Most perimeters are also capable of testing up to 80 or 90 degrees.

Another method is for the practitioner to hold up 1, 2, or 5 fingers in the four quadrants and center of a patient's visual field (with the other eye covered). If the patient is able to report the number of fingers properly as compared with the visual field of the practitioner, the normal result is recorded as "full to finger counting" (often abbreviated FTFC). The blind spot can also be assessed via holding a small object between the practitioner and the patient. By comparing when the object disappears for the practitioner, a subject's blind spot can be identified. There are many variants of this type of exam (e.g., wiggling fingers at visual periphery in the cardinal axes).

Visual field loss

Visual field loss may occur due to disease or disorders of the eye, optic nerve, or brain. Classically, there are four types of visual field defects:[8]

- Altitudinal field defects, loss of vision above or below the horizontal – associated with ocular abnormalities

- Bitemporal hemianopia, loss of vision at the sides (see below)

- Central scotoma, loss of central vision

- Homonymous hemianopia, loss at one side of the visual field for both eyes – defect located behind optic chiasm (see below)

Different neurological difficulties cause characteristic forms of visual disturbances, including hemianopsias (shown below without macular sparing), quadrantanopsia, and others.

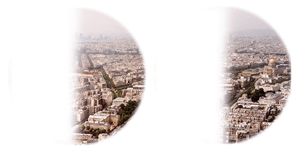

Paris as seen with full visual fields |

Paris as seen with bitemporal hemianopsia |

Paris as seen with binasal hemianopsia |

Paris as seen with left homonymous hemianopsia |

Paris as seen with right homonymous hemianopsia |

See also

- Visual field test

- Biased Competition Theory

- Divided visual field paradigm

- Receptive field

- Peripheral vision

- Visual Snow

References

- ↑ Smythies J (1996). "A note on the concept of the visual field in neurology, psychology, and visual neuroscience". Perception. 25 (3): 369–71. PMID 8804101. doi:10.1068/p250369.

- ↑ Rönne, Henning (1915). "Zur Theorie und Technik der Bjerrrumschen Gesichtsfelduntersuchung". Archiv für Augenheilkunde. 78 (4): 284–301.

- ↑ Traquair, Harry Moss (1938). An Introduction to Clinical Perimetry, Chpt. 1. London: Henry Kimpton. pp. 4–5.

- ↑ Robert H. Spector (1990). Clinical Methods: The History, Physical, and Laboratory Examinations. 3rd edition.

- ↑ Similar limits were already reported in the 19th century by Alexander Hueck (1840, p. 84): „Outwards from the line of sight I found an extent of 110°, inwards only 70°, downwards 95°, upwards 85°. When looking into the distance we thus overlook 220° of the horizon.” Hueck, A. (1840). Von den Gränzen des Sehvermögens. Archiv für Anatomie, Physiologie und wissenschaftliche Medicin, 82-97.

- ↑ Strasburger, H.; Rentschler, I.; Jüttner, M. (2011). "Peripheral vision and pattern recognition: a review". Journal of Vision. 11 (5): 1–82. doi:10.1167/11.5.13.

- ↑ Polyak, S. L. (1941). The Retina. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

- ↑ Jay WM (1981). "Visual field defects". American Family Physician. 24 (2): 138–42. PMID 7258077.

External links

- MedlinePlus Encyclopedia Visual Field

- Patient Plus

- Quadrantanopsia Visual Fields Teaching Case from MedPix

- Strasburger, Hans; Rentschler, Ingo; Jüttner, Martin (2011). Peripheral vision and pattern recognition: a review. Journal of Vision, 11(5):13, 1–82.

- Software for visual psychophysics; VisionScience.com