Thomas Hart Benton (politician)

| Thomas Hart Benton | |

|---|---|

|

Oil portrait (detail) c. 1861 from the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, D.C. | |

| United States Senator from Missouri | |

|

In office August 10, 1821 – March 4, 1851 | |

| Preceded by | (Constituency created) |

| Succeeded by | Henry S. Geyer |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Missouri's 1st district | |

|

In office March 4, 1853 – March 3, 1855 | |

| Preceded by | John F. Darby |

| Succeeded by | Luther M. Kennett |

| Member of the Tennessee Senate | |

|

In office 1809–1811 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

March 14, 1782 Harts Mill, North Carolina |

| Died |

April 10, 1858 (aged 76) Washington D.C. |

| Political party | Democratic-Republican, Democratic |

| Spouse(s) | Elizabeth Preston McDowell |

| Alma mater | University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill |

| Signature |

|

| Military service | |

| Service/branch | United States Army |

| Years of service | 1812–1815 |

| Rank | Lieutenant Colonel |

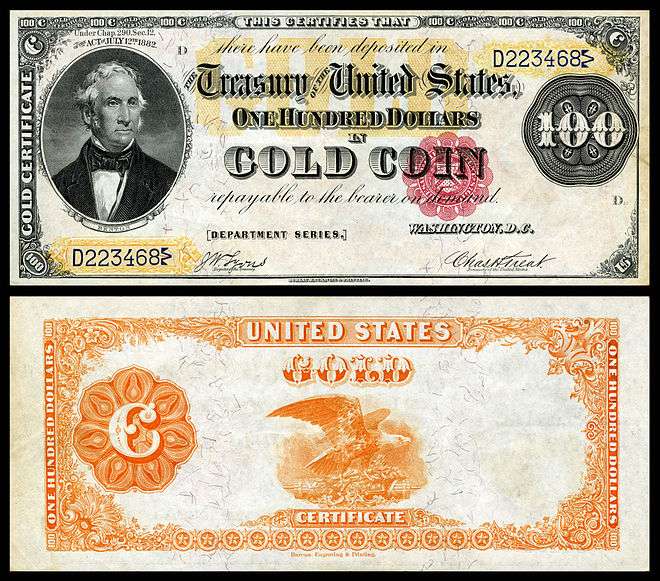

Thomas Hart Benton (March 14, 1782 – April 10, 1858), nicknamed "Old Bullion", was a U.S. Senator from Missouri and a staunch advocate of westward expansion of the United States. He served in the Senate from 1821 to 1851, becoming the first member of that body to serve five terms. Benton was a strong supporter of the Democratic Party, and of President Andrew Jackson, whose ideas provided the basis for the party's founding. Benton was an architect and champion of westward expansion by the United States, a cause that became known as Manifest Destiny.

Early life

Thomas Hart Benton was born in Harts Mill, North Carolina, near the present-day town of Hillsborough. His father Jesse Benton, a wealthy lawyer and landowner, died in 1790. His grandfather Samuel Benton[1][2] (c. 1720–1770) was born in Worcester, England, and settled in the Province of North Carolina. Thomas H. Benton also studied law at the University of North Carolina[3] where he was a member of the Philanthropic Society, but in 1799 he was dismissed from school after admitting to stealing money from fellow students. As Benton was leaving campus on the day he was expelled, he turned to the students who were jeering him and said,"I am leaving here now but damn you, you will hear from me again." He then left school to manage the Benton family estate, but historians posit that Benton used the events as motivation to prove himself worthy in adulthood.

Attracted by the opportunities in the West, the young Benton moved the family to a 40,000 acre (160 km²) holding near Nashville, Tennessee. Here he established a plantation with accompanying schools, churches, and mills. His experience as a pioneer instilled a devotion to Jeffersonian democracy which continued through his political career.

He continued his legal education and was admitted to the Tennessee bar in 1805, and in 1809 served a term as state senator.[4] He attracted the attention of Tennessee's "first citizen" Andrew Jackson, under whose tutelage he remained during the Tennessee years.

At the outbreak of the War of 1812, Jackson made Benton his aide-de-camp, with a commission as a lieutenant colonel. Benton was assigned to represent Jackson's interests to military officials in Washington D.C.; he chafed under the position, which denied him combat experience. In 1813 Benton engaged in a frontier brawl with Jackson in which Jackson was wounded.[5]

After the war, in 1815, Benton moved his estate to the newly opened Missouri Territory. As a Tennessean, he was under Jackson's shadow; in Missouri, he could be a big fish in the as-yet small pond. He settled in St. Louis, where he practiced law and edited the Missouri Enquirer, the second major newspaper west of the Mississippi River.

In 1817 during a court case he and opposing attorney Charles Lucas accused each other of lying. When Lucas ran into him at the voting polls he accused Benton of being delinquent in paying his taxes and thus should not be allowed to vote. Benton accused Lucas of being a "puppy" and Lucas challenged Benton to a duel. They had a duel on Bloody Island with Lucas being shot through the throat and Benton grazed in the knee. Upon bleeding profusely, Lucas said he was satisfied and Benton released him from completing the duel. However rumors circulated that Benton, a better shot, had made the rules of 30 feet apart to favor him. Benton challenged Lucas to a rematch on Bloody Island with shots fired from nine feet. Lucas was shot close to the heart and before dying initially told Benton, "I do not or cannot forgive you." As death approached Lucas then stated "I can forgive you—I do forgive you."[6]

United States Senate career

.jpg)

The Missouri Compromise of 1820 made the territory into a state, and Benton was elected as one of its first senators.

After the presidential election of 1824, in which candidate Andrew Jackson received a plurality but not a majority of votes and lost to John Quincy Adams in the House of Representatives, Benton and Jackson put their personal differences behind them and joined forces. Benton became the senatorial leader for the Democratic Party and argued vigorously against the Bank of the United States. Jackson was censured by the Senate in 1834 for canceling the Bank's charter.[7] At the close of the Jackson presidency, Benton led a successful "expungement campaign" in 1837 to remove the censure motion from the official record.[8]

Benton was an unflagging advocate for "hard money", that is gold coin (specie) or bullion as money—as opposed to paper money "backed" by gold as in a "gold standard". "Soft" (i.e. paper or credit) currency, in his opinion, favored rich urban Easterners at the expense of the small farmers and tradespeople of the West. He proposed a law requiring payment for federal land in hard currency only, which was defeated in Congress but later enshrined in an executive order, the Specie Circular, by Jackson (1836). His position on currency earned him the nickname Old Bullion.[9]

Senator Benton's greatest concern, however, was the territorial expansion of the United States to meet its "manifest destiny" as a continental power. He originally considered the natural border of the U.S. to be the Rocky Mountains, but expanded his view to encompass the Pacific coast. He considered unsettled land to be insecure, and tirelessly worked for settlement. His efforts against soft money were mostly to discourage land speculation, and thus encourage settlement.

Benton was instrumental in the sole administration of the Oregon Territory. Since the Anglo-American Convention of 1818, Oregon had been jointly occupied by both the United States and the United Kingdom. Benton pushed for a settlement on Oregon and the Canada–US border favorable to the United States. The current border at the 49th parallel set by the Oregon Treaty in 1846 was his choice; he was opposed to the extremism of the "Fifty-four forty or fight" movement during the Oregon boundary dispute.

Benton was the author of the first Homestead Acts, which encouraged settlement by giving land grants to anyone willing to work the soil. He pushed for greater exploration of the West, including support for his son-in-law John C. Frémont's numerous treks. He pushed hard for public support of the intercontinental railway and advocated greater use of the telegraph for long-distance communication. He was also a staunch advocate of the disenfranchisement and displacement of Native Americans in favor of European settlers.

He was an orator and leader of the first class, able to stand his own with or against fellow senators Daniel Webster, Henry Clay, and John C. Calhoun. Although an expansionist, his personal morals made him opposed to greedy or underhanded behavior—thus his opposition to Fifty-Four Forty. Benton advocated the annexation of Texas and argued for abrogation of the 1819 Adams-Onís Treaty in which the United States relinquished claims to that territory, but he was opposed to the machinations that led to its annexation in 1845 and the Mexican-American War. He believed that expansion was for the good of the country, and not for the benefit of powerful individuals.

On February 28, 1844, Benton was present at the USS Princeton explosion when a cannon misfired on deck while giving a tour of the Potomac River. The incident killed more than seven people, including United States Secretary of State Abel P. Upshur and United States Secretary of the Navy Thomas W. Gilmer, and wounded over twenty. Benton was one of the injured, but his injury was not serious and he did not miss one day from the Senate.

His loyalty to the Democratic Party was legendary. Benton was the legislative right-hand-man for Andrew Jackson, and continued this role for Martin Van Buren. With the election of James K. Polk, however, his power began to ebb, and his views diverged from the party's. His career took a distinct downturn with the issue of slavery. Benton, a southerner and slave owner, became increasingly uncomfortable with the topic. He was also at odds with fellow Democrats, such as John C. Calhoun, who he thought put their opinions ahead of the Union to a treasonous degree. With troubled conscience, in 1849 he declared himself "against the institution of slavery," putting him against his party and popular opinion in his state. In April 1850, during heated Senate floor debates over the proposed Compromise of 1850, Benton was nearly shot by pistol-wielding Mississippi Senator Henry S. Foote, who had taken umbrage to Benton's vitriolic sparring with Vice-President Millard Fillmore. Foote was wrestled to the floor, where he was disarmed.

Later life

In 1851, Benton was denied a sixth term by the Missouri legislature; the polarization of the slavery issue made it impossible for a moderate and unionist to hold that state's senatorial seat. In 1852 he successfully ran for the United States House of Representatives, but his opposition to the Kansas-Nebraska Act led to his defeat in 1854. He ran for Governor of Missouri in 1856, but lost to Trusten Polk. The same year his son-in-law, John C. Frémont, husband of his daughter Jessie ran for President on the Republican Party ticket, but Benton was a party loyalist to the end, and voted Democratic, the Democratic candidate that year being James Buchanan, who won the election.

He was elected a member of the American Antiquarian Society in 1855.[10]

He published his autobiography, Thirty Years' View, in 1854, and died in Washington D.C. on April 10, 1858. His descendants have continued to be prominent in Missouri life; his great-grandnephew, also Thomas Hart Benton, was a 20th-century painter.

Benton is buried at Bellefontaine Cemetery in St. Louis.

Family connections

Benton was related by marriage or blood to a number of 19th-century luminaries. Two of his nephews—Confederate Colonel and posthumous Brigadier General Samuel Benton[11] of Mississippi and Union Colonel and Brevet Brigadier General Thomas H. Benton, Jr. of Iowa[12]—fought on opposite sides during the Civil War. He was brother-in-law of Senator/Governor James McDowell of Virginia; father-in-law of explorer, Union Major General, and presidential candidate John C. Frémont; and cousin-in-law of Senators Henry Clay[13] and James Brown, both of whom married cousins of Benton. His great-nephew was Congressman Maecenas Eason Benton, the father of painter Thomas Hart Benton.

Legacy

Seven states (Arkansas, Indiana, Iowa, Minnesota, Missouri, Oregon, and Washington) have counties named after Benton. Two counties (Calhoun County, Alabama and Hernando County, Florida) were formerly named Benton County in his honor. During Reconstruction, Benton County, Mississippi, was misrepresented by residents as being named after Benton. Bentonville, Indiana was named for the senator,[14] as were Bentonville, Arkansas and Benton Harbor, Michigan. Additionally, the fur trading post and now community of Fort Benton, Montana was named after Benton.[15]

Uniquely, Benton has been the subject of biographical study by two men who later became presidents of the United States. In 1887, Theodore Roosevelt published a biography of Benton.[16] Benton is also one of the eight senators profiled in John F. Kennedy's Profiles in Courage.[17]

Quotations

- "Nobody opposes Benton, sir, nobody but a few black-jack prairie lawyers. These are the only opponents of Benton. Benton and the people, Benton and Democracy are one and the same sir, synonymous terms, sir, synonymous terms."[18]

- "I never quarrel, sir, but I do fight, sir, and when I fight, sir, a funeral follows, sir."[19]

- "Yes, sir, I knew him, sir; General Jackson was a very great man, sir. I shot him, sir. Afterward he was of great use to me, sir, in my battle with the United States Bank." (When asked if he knew Andrew Jackson)[20]

- "When Andrew Jackson starts talking about hanging, men begin looking for ropes." (During the Nullification Crisis)

- "I never called your name, sir. Turn your profile to the audience... citizens, that is not the profile of a man; it is the profile of a dog."

References

- ↑ http://www.familysearch.org/eng/default.asp

- ↑ http://mostateparks.com/page/55154/benton-genealogy

- ↑ Violette, Eugene (1918). History of Missouri. New York: D.C. Heath & Co. p. 275.

- ↑ Morrow, 261.

- ↑ Meacham, Jon. American Lion: Andrew Jackson in the White House. New York: Random House, 2009 (29-30).

- ↑ Meigs, William (1904). The Life of Thomas Hart Benton (Ch. 8 "The Lucas Duels"). Philadelphia : J.B. Lippincott. pp. 104–116.

- ↑ Meacham, Jon. American Lion: Andrew Jackson in the White House. New York: Random House, 2009 (279).

- ↑ Meacham, Jon. American Lion: Andrew Jackson in the White House. New York: Random House, 2009 (335-37).

- ↑ Violette, 262. Also, alliteratively, "Bullion Benton"; see Heidler and Heidler, 275.

- ↑ American Antiquarian Society Members Directory

- ↑ Eicher, John H.; Eicher, David J. (2001), Civil War High Commands, Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, pp. 589–590, ISBN 0-8047-3641-3

- ↑ Eicher, John H.; Eicher, David J. (2001), Civil War High Commands, Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, p. 129, ISBN 0-8047-3641-3

- ↑ Heidler, David S. and Jeanne T. Heidler. Henry Clay: The Essential American. New York: Random House, 2010 (146).

- ↑ History of Fayette County, Indiana. Warner, Beers and Company. 1885. p. 226.

- ↑ Gannett, Henry (1905). The Origin of Certain Place Names in the United States. Govt. Print. Off. p. 128.

- ↑ Morris, Edmund. The Rise of Theodore Roosevelt, Revised and Updated. New York: The Modern Library, 2001. (328). Morris attributes Roosevelt's belief in manifest destiny to Benton (see Morris, 392).

- ↑ John F. Kennedy. Profiles in Courage. Harper and Brothers, 1956.

- ↑ Kennedy, John F. (2006). "4: Thomas Hart Benton". Profiles in Courage (1st Harper Perennial Modern Classics ed., 50th Anniversary ed.). New York: HarperPerennial Modern Classics. p. 77. ISBN 978-0-06-085493-5. Retrieved 5 October 2011.

- ↑ Kennedy, John F. (2006). "4: Thomas Hart Benton". Profiles in courage (1st Harper Perennial Modern Classics ed., 50th Anniversary ed.). New York: HarperPerennial Modern Classics. p. 75. ISBN 978-0-06-085493-5. Retrieved 5 October 2011.

- ↑ Kennedy, John F. (2006). "4: Thomas Hart Benton". Profiles in courage (1st Harper Perennial Modern Classics ed., 50th Anniversary ed.). New York: HarperPerennial Modern Classics. p. 75. ISBN 978-0-06-085493-5. Retrieved 5 October 2011.

Further reading

- Chambers, William Nisbet. Old Bullion Benton, Senator from the New West: Thomas Hart Benton, 1782-1858 (1958); Scholarly biography

- Meigs, William Montgomery. The Life of Thomas Hart Benton (1904), Very old scholarly biography; online

- Mueller, Ken S. Senator Benton and the People: Master Race Democracy on the Early American Frontier (2014) ISBN 978-0-87580-700-3 (paper) ISBN 978-0-87580-479-8 (cloth)

- Roosevelt, Theodore. Thomas Hart Benton ISBN 0-559-32542-8 (1886; 2008 edition), popular biography Google books

- Smith, Elbert B. Magnificent Missourian: The Life of Thomas Hart Benton (1973), Scholarly biography

Primary source

- Benton, Thomas Hart. Thirty Years' View (1854); His autobiography; online

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Thomas Hart Benton (senator). |

| Wikisource has the text of a 1900 Appletons' Cyclopædia of American Biography article about Thomas Hart Benton. |

- United States Congress. "Thomas Hart Benton (id: B000398)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress.

- Works by Thomas Hart Benton at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Thomas Hart Benton at Internet Archive

- Thomas Hart Benton Collection Missouri History Museum

- Thomas Hart Benton at Find a Grave

| U.S. Senate | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by (none) |

U.S. Senator (Class 1) from Missouri August 10, 1821 – March 4, 1851 Served alongside: David Barton, Alexander Buckner, Lewis F. Linn and David Rice Atchison |

Succeeded by Henry S. Geyer |

| U.S. House of Representatives | ||

| Preceded by John F. Darby |

Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Missouri's 1st congressional district March 4, 1853 – March 4, 1855 |

Succeeded by Luther M. Kennett |