United States Senate Watergate Committee

| Special committee | |

|---|---|

Defunct United States Senate 93rd Congress | |

| History | |

| Formed | February 7, 1973 |

| Disbanded | abolished after June 27, 1974, when the committee's final report was published |

| Leadership | |

| Chair | Sam Ervin (D) |

| Ranking member | Howard Baker (R) |

| Structure | |

| Seats | 7 members |

| Political parties |

Majority (4) |

| Jurisdiction | |

| Purpose | To investigate "illegal, improper, or unethical activities" conducted by individuals involved with a campaign, nomination, and/or election of any candidate for President of the United States in the 1972 presidential election, and produce a final report with the committee's findings. |

| Rules | |

|

| |

| Watergate scandal |

|---|

| Events |

| People |

|

Watergate burglars |

|

Judiciary |

|

Intelligence community |

The Senate Watergate Committee, known officially as the Select Committee on Presidential Campaign Activities, was a special committee established by the United States Senate, S.Res. 60, in 1973, to investigate the Watergate scandal, with the power to investigate the break-in at the Democratic National Committee (DNC) headquarters at the Watergate office complex in Washington, D.C., and any subsequent cover-up of criminal activity, as well as "all other illegal, improper, or unethical conduct occurring during the presidential election of 1972, including political espionage and campaign finance practices".

American print news media focused the nation's attention on the issue with hard-hitting investigative reports, while television news outlets brought the drama of the hearings to the living rooms of millions of American households, broadcasting the proceedings live for two weeks in May 1973. The public television network PBS broadcast the hearings from gavel to gavel on more than 150 national affiliates.

Working under committee chairman Sam Ervin (D-North Carolina), the committee played a pivotal role in gathering evidence that would lead to the indictment of forty administration officials and the conviction of several of Nixon's aides for obstruction of justice and other crimes. Its revelations prompted the impeachment process against Richard Nixon, which featured the introduction of articles of impeachment against the President in the House of Representatives, which led to Nixon's resignation on August 9, 1974.

Background

Shortly after midnight on June 17, 1972, Frank Wills, a security guard at the Watergate Complex, noticed tape covering the latches on some of the doors in the complex leading from the underground parking garage to several offices (allowing the doors to close but remain unlocked). He removed the tape, and thought nothing of it. He returned an hour later and, having discovered that someone had retaped the locks, Wills called the police. Five men were discovered inside the DNC office and arrested.[1] They were Virgilio González, Bernard Barker, James McCord, Eugenio Martínez, and Frank Sturgis, who were charged with attempted burglary and attempted interception of telephone and other communications. On September 15, a grand jury indicted them, as well as E. Howard Hunt and G. Gordon Liddy,[2] for conspiracy, burglary, and violation of federal wiretapping laws. The five burglars who broke into the office were tried by a jury, Judge John Sirica officiating, and were convicted on January 30, 1973.[3]

While the burglars awaited their arraignment in federal district court, the FBI launched an investigation of the incident. The dogged reporting of two Washington Post journalists, Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein, raised questions and suggested connections between Richard Nixon’s reelection campaign and the men awaiting trial in federal district court. The White House denied any connection to the break-in, and Nixon won reelection in a landslide in November 1972.[4] Following confirmation that such a connection did in fact exist, the Senate voted 77-0 in February 1973 to create the Select Committee on Presidential Campaign Activities.[5]

Members

The members of the Senate Watergate Committee were:

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The chief counsel of the Committee was Samuel Dash, who directed the investigation. The minority counsel was Fred Thompson. Members of the Senate Watergate Committee’s professional staff included:

- Rufus Edmisten (Deputy Counsel)

- Donald Sanders (Deputy Minority Counsel - Republican)

- Terry Lenzner, chief investigator[6]

- Scott Armstrong

- Robert Muse

- Marc Lackritz

- Gordon L. Freedman

Hearings

Hearings opened on May 17, 1973, and the Committee issued its seven-volume, 1,250-page report on June 27, 1974, entitled Report on Presidential Campaign Activities. The first weeks of the committee's hearings were a national politico-cultural event. They were broadcast live during the day on commercial television; at the start, CBS, NBC, and ABC covered them simultaneously, and then later on a rotation basis, while PBS replayed the hearings at night.[7] Some 319 hours were broadcast overall, and 85% of U.S. households watched some portion of them.[7] The audio feed also was broadcast gavel-to-gavel on scores of National Public Radio stations, making the hearings available to people in their cars and workplaces, and giving a major boost to the fledgling broadcast organization.

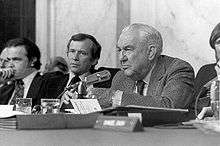

The hearings made stars out of both Ervin, who became known for his folksy manner and wisdom but resolute determination, and Baker, who appeared somewhat non-partisan and uttered the famous phrase "What did the President know, and when did he know it?" (often paraphrased by others in later scandals). It was the introduction to the public for minority counsel Thompson, who would later become an actor, senator, and presidential candidate. Many of Watergate's most famous moments happened during the hearings, including John Dean's "cancer on the Presidency" testimony and Alexander Butterfield's revelation of the existence of the secret White House Nixon tapes.

References

- ↑ "Watergate Scandal, 1973 In Review.". United Press International. September 8, 1973. Retrieved June 17, 2010.

- ↑ Dickinson, William B.; Mercer Cross; Barry Polsky (1973). "Watergate: Chronology of a Crisis". 1. Washington D. C.: Congressional Quarterly Inc.: 4. ISBN 0-87187-059-2. OCLC 20974031.

- ↑ Sirica, John J. (1979). To Set the Record Straight: The Break-in, the Tapes, the Conspirators, the Pardon. New York: Norton. p. 44. ISBN 0-393-01234-4.

- ↑ "Select Committee on Presidential Campaign Activities (The Watergate Committee)". Senate Historical Office. Retrieved December 31, 2016.

- ↑ "March 28, 1973: Watergate Leaks Lead to Open Hearings". Senate Historical Office. Retrieved December 31, 2016.

- ↑ The $100,000 Misunderstanding, Time Magazine, May 6, 1974

- 1 2 Ronald Garay, "Watergate", Museum of Broadcast Communications. Accessed June 30, 2007.