Selma Burke

| Selma Burke | |

|---|---|

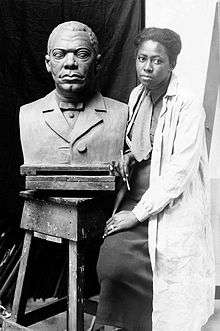

Burke with her portrait bust of Booker T. Washington, c. 1935 | |

| Born |

Selma Hortense Burke December 31, 1900 Mooresville, North Carolina, United States |

| Died | August 29, 1995 (aged 94) |

| Nationality | American |

| Education | Columbia University |

| Known for | Sculpture |

Selma Hortense Burke (December 31, 1900 – August 29, 1995) was an American sculptor and a member of the Harlem Renaissance movement.[1] Burke is best known for her bas relief of President Franklin D. Roosevelt on the Recorder of Deeds Building in Washington, D.C.[2] Her other work includes a bust of Duke Ellington, portraits of Mary McLeod Bethune and Booker T. Washington, and sculptures of John Brown (abolitionist) and President Calvin Coolidge.[3]

Biography

Selma Burke was born on December 31, 1900, in Mooresville, North Carolina, the seventh of 10 children of Neal and Mary Jackson Burke. Her father was an AME Church Minister.[4] As a child, she attended a one-room segregated schoolhouse.[3] Her interest in sculpting was ignited by her maternal grandmother, who was a painter, although her mother thought she should pursue a more marketable vocation.[5] Her father nurtured her interest in art by bringing home souvenirs and art objects from his international travels in Europe, Africa, and the Caribbean as an ocean liner chef.[5]

Burke attended Winston-Salem State University, and then graduated in 1924 from the St. Agnes Training School for Nurses in Raleigh. She moved to Harlem, where she found work as a private nurse.[4][6]

Burke became involved in the Harlem Renaissance during her marriage to Claude McKay. She worked for the Works Progress Administration and the Harlem Artists Guild, teaching art to children in Harlem. One of her WPA works, a bust of Booker T. Washington, was given to Frederick Douglass High School in Manhattan in 1936.[7]

In the late 1930s she traveled to Europe on a Rosenwald fellowship to study sculpture in Vienna and in Paris with Aristide Maillol. In 1940 she founded the Selma Burke School of Sculpture in New York City, finishing a Master of Fine Arts degree at Columbia University the following year.[4][8]

She was committed to teaching art; after teaching at her in New York City school, Burke opened the Selma Burke Art Center in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.[2][9] Open from 1968 to 1981, the center "was an original art center that played an integral role in the Pittsburgh art community," offering courses ranging from studio workshops to puppetry classes.[10]

Burke retired to New Hope, Pennsylvania, and died in 1995, at the age of 94.[3]

Selected work

After competing in a national contest, Burke won a commission to sculpt a portrait honoring then-President Franklin D. Roosevelt and the Four Freedoms. She created the sculpture based on sketches made during a 45-minute sitting with Roosevelt at the White House.[2] The 3.5-by-2.5-foot plaque was completed in 1944 and unveiled in September 1945 at the Recorder of Deeds Building in Washington, D.C., where it still hangs today.[10] It is generally accepted, although not without some controversy, that John R. Sinnock's obverse design on the Roosevelt dime was based on Burke's plaque.[3][11][12][13] Sinnock later denied that Burke's portrait was an influence.[14][15]

Burke's other public sculpture pieces include a bust of Duke Ellington at the Performing Arts Center in Milwaukee, as well as works on display at the Hill House Center in Pittsburgh, the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture in New York City, Atlanta University, Spelman College, and the Smithsonian Museum of American Art.[16]

Selma Burke was among the artists featured at The National Urban League's inaugural exhibition at Gallery 62 in 1978.[17] Her last monumental work, created in 1980 when she was 80 years old, is a bronze statue of Martin Luther King, Jr. in Charlotte, N.C.[3]

Honors

Burke is an honorary member of Delta Sigma Theta sorority.[18] She received three honorary doctorate degrees during her lifetime, including one awarded by Livingston College in 1970.[3][4] Milton Shapp, then-governor of Pennsylvania, declared July 29, 1975, Selma Burke Day in recognition of the artist's contributions to art and education.[19]

Burke was a member of the first group of women – along with Louise Nevelson, Alice Neel, Georgia O'Keefe, and Isabel Bishop – to receive lifetime achievement awards from the Women's Caucus for Art, in 1979.[20] She received the award from President Jimmy Carter in a private ceremony in the Oval Office.[21][22] She received a Candace Award from the National Coalition of 100 Black Women in 1983.[23]

References

- ↑ "Burke, Selma - Oxford Reference". doi:10.1093/acref/9780195373219.001.0001/acref-9780195373219-e-220.

- 1 2 3 "Selma Burke; Sculptor, 94". The New York Times. Retrieved December 17, 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Wallace, Andy (September 1, 1995). "Selma Burke, 94, Black Sculptor Whose Profile Of Fdr Graces Dime". Seattle Times. Retrieved March 4, 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 Mack, Felicia. "Burke, Selma Hortense (1900-1995)". BlackPast. Retrieved December 17, 2011.

- 1 2 Kirschke, Amy (2014). Women Artists of the Harlem Renaissance. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi. p. 119.

- ↑ Santandrea, Lisa (January 1, 2001). "Nurses Making a Difference". The American Journal of Nursing. 101 (2): 86–87.

- ↑ Carr, Eleanor (January 1, 1972). "New York Sculpture during the Federal Project". Art Journal. 31 (4): 397–403. doi:10.2307/775543.

- ↑ Lewis, David Levering (January 1, 1984). "Parallels and Divergences: Assimilationist Strategies of Afro-American and Jewish Elites from 1910 to the Early 1930s". The Journal of American History. 71 (3): 543–564. doi:10.2307/1887471.

- ↑ Stahl, Joan. "Selma Burke". Retrieved December 17, 2011.

- 1 2 Verderame, Lori. "The Sculptural Legacy Of Selma Burke, 1900-1995". Retrieved December 17, 2011.

- ↑ Meschutt, David (January 1, 1986). "Portraits of Franklin Delano Roosevelt". American Art Journal. 18 (4): 3–50. doi:10.2307/1594463.

- ↑ Faxon, Alicia Craig (January 1, 2005). "Review of Creating Their Own Image: The History of African-American Women Artists". Woman's Art Journal. 26 (2): 45–46. doi:10.2307/3598099.

- ↑ Turner, Elizabeth H. (January 1, 1990). "Review of A New Perspective: Southern Women's Cultural History from the Civil War to Civil Rights". The Georgia Historical Quarterly. 74 (2): 337–339.

- ↑ Yanchunas, Dom. "The Roosevelt Dime at 60." COINage Magazine, February 2006.

- ↑ "John R. Sinnock, Coin Designer". The Numismatic Scrapbook Magazine: 261. March 15, 1946.

- ↑ "SIRIS - Smithsonian Institution Research Information System". siris-artinventories.si.edu. Retrieved March 12, 2017.

- ↑ Hajosy, Dolores (January 1, 1985). "Gallery 62: An Outlet... A Bridge". Black American Literature Forum. 19 (1): 22–23. doi:10.2307/2904467.

- ↑ "Dr. Selma Burke: A Gifted Artist with Many Accomplishments with". African American Registry. Retrieved December 17, 2011.

- ↑ Gumbo Ya Ya: Anthology of Contemporary African-American Women Artists. New York: Midmarch Arts Press. 1995. p. 29.

- ↑ Porter, Nancy (January 1, 1979). "Surviving as Women Artists: Two Art History Sessions". Women's Studies Newsletter. 7 (3): 12–14.

- ↑ Halamka, Kathy A. (2007). "Report on the History of the Women's Caucus For Art" (PDF). Cambridge Scholars Press.

- ↑ "Reports on the 67th Annual College Art Association Meeting". Art Journal. 38 (4): 283–285. January 1, 1979.

- ↑ "Candace Award Recipients 1982–1990, page 1". National Coalition of 100 Black Women. Archived from the original on March 14, 2003.

Further reading

- Jones, Frederick N.; Burke, Selma (2007). Out of the miry clay : artistic creativity and spirituality in the making of Selma Burke's art : a study of history, theory/theology, methodology and impact. Columbus, Ga. : Brentwood Christian Press.

- Farrington, Lisa E. (2011). Creating their own image : the history of African-American women artists. Oxford ; New York: Oxford University Press.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Selma Burke. |

- Entry for Selma Burke on the Union List of Artist Names

- Selma Burke's entry on the African-American Registry

- October Gallery

- Kennedy Center biography of Selma Burke

- Long Island University biography