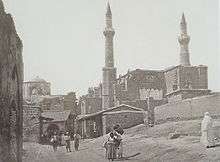

St. Sophia Cathedral, Nicosia

| Selimiye Mosque | |

|---|---|

| Selimiye Camii / Τέμενος Σελιμιγιέ | |

| |

| Basic information | |

| Location |

de facto North Nicosia, Northern Cyprus de jure Nicosia, Cyprus |

| Geographic coordinates | 35°10′35″N 33°21′52″E / 35.1765°N 33.3645°ECoordinates: 35°10′35″N 33°21′52″E / 35.1765°N 33.3645°E |

| Affiliation |

|

| District |

de facto Lefkoşa District de jure Nicosia District |

| Country | Cyprus |

| Year consecrated | 1326 |

| Status | Active as a mosque |

| Architectural description | |

| Architectural style | Gothic |

| Groundbreaking | 1209 |

| Specifications | |

| Capacity | 2500 |

| Minaret(s) | 2 |

Selimiye Mosque, historically known as Cathedral of Saint Sophia, is a former Roman Catholic cathedral converted into a mosque, located in North Nicosia. It is the main mosque of the city. The Selimiye Mosque is housed in the largest and oldest surviving Gothic church in Cyprus (interior dimensions: 66 X 21 m) possibly constructed on the site of an earlier Byzantine church.

In total, the mosque has a capacity to hold 2500 worshipers with 1750 m2 available for worship.[1]

History

Earlier Byzantine church

The name of the cathedral derives from Ayia Sophia, meaning "Holy Wisdom" in Greek. According to Kevork K. Keshishian, the dedication of the cathedral to the Holy Wisdom is a remnant from the Byzantine cathedral, which occupied the same place.[2] However, such a cathedral is absent from Byzantine sources and is not associated with any excavated ruins. In spite of this, there is evidence of the existence of such a cathedral; an 11th-century manuscript mentions the existence of an episcopal church dedicated to Holy Wisdom in the city.[3]

Construction and Frankish period

The construction of the cathedral began in 1209, when Thierry, the Archbishop of Cyprus, lay the foundations of the cathedral,[4] however, there are claims of evidence indicating an earlier beginning date.[5] Halil Fikret Alasya, however, credits Eustorge de Montaigu, the Archbishop of Cyprus during the early years of the Frankish rule with the commencement of the construction. in 1208,[6] By 1228, the church was "largely completed" under Eustorge.[4] The arrival of Louis IX of France in Cyprus in 1248 for the Seventh Crusade gave a boost to the construction.[7] By the end of the 13th century the side aisles and a large part of the middle aisle were completed.

During the 13th and 14th centuries, the cathedral was damaged twice by earthquakes, in 1267 or 1270 and 1303.[7] The 1267/1270 earthquake caused significant delay in the construction of the nave.[8] Giovanni del Conte, Latin archbishop of Nicosia, oversaw the completion of the nave and the narthex until 1319[5] and that of the middle aisle, the buttresses of the chevet, the façade and a chapel/baptistery from 1319 to 1326. He also initiated the adornment of the cathedral with frescoes, sculptures,[9] marble screens and wall paintings. In 1326, the cathedral was finally consecrated and officially inaugurated with a great celebration.[8][9]

Even though the cathedral was inaugurated, the building was still incomplete and in 1347 Pope Clement IV issued a papal bull for the cathedral to be completed and renovated since it had been affected by an earthquake. The bull gave a 100-day period of indulgence for those who participated in the completion of the cathedral,[10] however, this effort did not achieve its aim.[2] The portico and the northwest tower were constructed at this time and the three gates of the western wall were embellished with structures. Kings, prophets, apostles and bishops were depicted at the reliefs in three arches.[9]

In 1359, the Papal legate in Cyprus, Peter Thomas, assembled all Greek Orthodox bishops of Cyprus in the cathedral, locked them in and began preaching in order to convert them. The sound of shouting coming from the cathedral gathered a large crowd outside the cathedral, which soon began a riot to free the priests and burned the doors of the cathedral. The king ordered the rescue of the preacher, who would later be reprimanded, from the mob, and the freeing of the bishops.[11]

In 1373, the cathedral suffered damage during the Genoese raids on Cyprus.[7]

Venetian period

In 1491, the cathedral was severely damaged by an earthquake. A visiting pilgrim described that a large part of the choir fell, the chapel of sacraments behind the choir was destroyed and a tomb that purportedly belonged to Hugh III of Cyprus was damaged, revealing his intact body in royal clothing and golden relics. The golden treasure was taken by the Venetians.[12] The Venetian Senate ordered the repair of the damage and set up a special commission, which taxed an annual contribution of 250 ducats from the archbishop. The repair was very extensive and thorough; in 1507, Pierre Mésenge wrote that despite the fact that the building was "totally demolished" 20 or 22 years ago, it then looked very beautiful.[13]

When the Venetians built their walls of Nicosia, St. Sophia's Cathedral became the center of the city. This reflected the position of medieval European cathedrals, around which the city was shaped.[14]

Ottoman period

During the 50-day Ottoman siege of the city in 1570, the cathedral provided refuge for a great number of people. When the city fell on 9 September, Francesco Contarini, the Bishop of Paphos, delivered the last Christian sermon in the building, in which he asked for divine help and exhorted the people. The cathedral was stormed by Ottoman soldiers, who broke the door and killed the bishop along with others. They smashed or threw out Christian items, such as furniture and ornaments in the cathedral[2] and destroyed the choir as well as the nave.[15] Then, they washed the interior of the mosque to make it ready for the first Friday prayer that it would host on 15 September, which was attended by the commander Lala Mustafa Pasha and saw the official conversion of the cathedral into a mosque.[2] During the same year, the two minarets were added, as well as Islamic features such as the mihrab and the minbar.[16]

The first imam of the mosque was Moravizade Ahmet Efendi, who hailed from the Morea province of the Ottoman Empire.[17] All imams maintained the tradition of climbing the stairs to the minbar before Friday sermons while leaning on a sword used during the conquest of Nicosia to signify that Nicosia was captured by conquest.[18]

Following its conversion, the mosque became the property of the Sultan Selim Foundation, which was responsible for maintaining it. Other donors formed a number of foundations to help with the maintenance. During the Ottoman period, it was the largest mosque in the whole island, and was used weekly by the Ottoman governor, administrators and elite for the Friday prayers. In the late 18th century, a large procession that consisted of the leading officials in the front on horseback, followed by lower-ranking officials on foot, came to the mosque every Friday.[19]

The Friday prayers also attracted a large number of Muslims from Nicosia and surrounding villages. Due to the crowds frequenting the mosque, a market developed next to it and the area became a trade center. The area around the mosque became a center of education as well, with madrasahs such as the Great Madrasah and Little Madrasah being built nearby.[15]

British rule and 20th century

In 1949, the imams stopped climbing to the minaret to read the adhan and started using loudspeakers instead. On 13 August 1954, the Mufti of Cyprus officially renamed the mosque "Selimiye Mosque", in honor of the Ottoman sultan Selim II, who headed the empire during the conquest of Cyprus.[2]

Burials in the church

(burials there when it was still a church)

Gallery

Selimiye Mosque, eastern view

Selimiye Mosque, eastern view

References

- Footnotes

- ↑ "Lefkoşa'ya 3657 mümin aranıyor". Haber Kıbrıs. 20 February 2011. Retrieved 9 January 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Keshishian, Kevork K. Nicosia: Capital of Cyprus Then and Now (2nd ed.). Nicosia: The Moufflon Book and Art Centre. pp. 173–8.

- ↑ Papacostas 2006, p. 11.

- 1 2 Coureas, Nicholas (1997). The Latin Church in Cyprus, 1195–1312 (illustrated ed.). Ashgate. p. 211. Retrieved 17 March 2015.

- 1 2 Riley-Smith, Jonathan (1999). A History of the Crusades. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780191579271.

- ↑ Alasya 2002, p. 383.

- 1 2 3 Güven 2014, p. 424.

- 1 2 Setton 1977, p. 168.

- 1 2 3 "Latin Cathedral of St. Sofia (Selimiye mosque)". Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Cyprus. Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- ↑ Papantoniou, Giorgos; Fitzgerald, Aoife; Hargis, Siobhán, eds. (2008). POCA 2005: Postgraduate Cypriot Archaeology : proceedings of the fifth annual Meeting of Young Researchers on Cypriot Archaeology, Department of Classics, Trinity College, Dublin, 21–22 October 2005. Archaeopress. p. 18. ISBN 9781407302904.

- ↑ Andrews 1999, p. 67.

- ↑ Setton 1977, p. 169.

- ↑ Enlart, Camille (1987). Gothic art and the Renaissance in Cyprus (illustrated ed.). Trigraph Limited. p. 88. ISBN 9780947961015.

- ↑ Erçin, Çilen (2014). "The Physical Formation of Nicosia in the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus from 13th to 15th Century" (PDF). Megaron Journal (in Turkish). Yıldız Teknik University. 9 (1): 34–44. Retrieved 15 March 2015.

- 1 2 Gürkan, Haşmet Muzaffer. Dünkü ve Bugünkü Lefkoşa (in Turkish) (3rd ed.). Galeri Kültür. pp. 117–8. ISBN 9963660037.

- ↑ Alasya 2002, p. 363.

- ↑ Bağışkan, Tuncer (31 May 2014). "Lefkoşa Şehidaları (1)". Yeni Düzen. Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- ↑ Fehmi, Hasan (1992). A'dan Z'ye KKTC: sosyal ve ansiklopedik bilgiler. Cem Publishing House. p. 129. Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- ↑ Bağışkan 2013.

- Bibliography

- Alasya, Halil Fikret (2012). "Kıbrıs". İslam Ansiklopedisi (in Turkish). 25. Türk Diyanet Vakfı. p. 383-4.

- Andrews, Justine M. (1999). "Santa Sophia in Nicosia: the Sculpture of the Western Portals and Its Reception". Comitatus: A Journal of Medieval and Renaissance Studies. UCLA. 30 (1): 63–90. Retrieved 15 March 2015.

- Bağışkan, Tuncer (21 September 2013). "Ayasofya (Selimiye) Meydanı ve Mahallesi" (in Turkish). Yeni Düzen. Retrieved 15 March 2015.

- Güven, Suna (2014). "St Sophia in Nicosia, Cyprus: From a Lusignan Cathedral to an Ottoman Mosque". In Mohammad, Gharipour. Sacred Precincts: The Religious Architecture of Non-Muslim Communities Across the Islamic World. BRILL. pp. 415–429. ISBN 9789004280229. Retrieved 17 March 2015.

- Papacostas, Tassos (2006). "In search of a lost Byzantine monument: Saint Sophia of Nicosia". Yearbook of Scientific Research Centers. Nicosia: 11–37. Retrieved 15 March 2015.

- Setton, Kenneth M.; Hazard, Harry W. (1977). "The Arts in Cyprus". A History of the Crusades: The Art and Architecture of the Crusader States (PDF). University of Wisconsin Press. pp. 165–207. ISBN 9780299068240. Retrieved 18 March 2015.

See also

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Category:Selimiye Mosque (St. Sophie Cathedral). |