Ahmed Sékou Touré

| Ahmed Sékou Touré | |

|---|---|

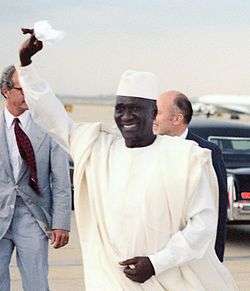

President Ahmed Sékou Touré of the Republic of Guinea arrives at Andrews Air Force Base in Maryland during a visit to Washington DC. (June 1982) | |

| 1st President of Guinea | |

|

In office October 2, 1958 – March 26, 1984 | |

| Preceded by | None (position first established) |

| Succeeded by | Louis Lansana Beavogui |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

January 9, 1922 Faranah, Guinea |

| Died |

March 26, 1984 (aged 62) Cleveland, Ohio, United States |

| Nationality | Guinean |

| Political party | Democratic Party of Guinea |

Ahmed Sékou Touré (var. Ahmed Sheku Turay) (January 9, 1922 – March 26, 1984) was a Guinean political leader who was elected as the first President of Guinea, serving from 1958 until his death in 1984. Touré was among the primary Guinean nationalists involved in gaining independence of the country from France.

In 1960, he declared his Parti démocratique de Guinée (PDG) the only legal party in the state, and ruled from then on as a virtual dictator. He was nominally re-elected to numerous seven year terms in the absence of any legal opposition. He imprisoned or exiled his strongest opposition leaders. It is estimated that 50,000 people were killed under his regime.[1]

Early life

Sékou Touré was born on January 9, 1922 into a Mandinka family in Faranah, French Guinea, then a colony of France. He was an aristocratic member of the Mandinka ethnic group.[2] His great-grandfather was Samory Touré, a noted Muslim Mandinka king who founded the Wassoulou Empire (1861-1890) in the territory of Guinea and Mali, defeating numerous small African states with his large, professionally organized and equipped army. He resisted French colonial rule until his capture in 1891. He died while held in exile in Gabon.[3]

Touré attended qur'anic school, lower-primary school, and vocational school. He worked for the Postal Services (French: Postes, télégraphes et téléphones (PTT)), and quickly became involved in labor union activity. During his youth, Touré studied the works of Karl Marx and Vladimir Lenin, among others.

Politics

Touré first became politically active while working for the PTT. In 1945, he founded the Post and Telecommunications Workers' Union (SPTT, the first trade union in French Guinea), and he became the general secretary of the Union in 1946.[4]

In 1952, he became the leader of the Guinean Democratic Party which was a local section of the RDA (African Democratic Rally, French: Rassemblement Démocratique Africain), a party agitating for the decolonization of Africa that included representatives from all the French West African colonies.

In 1953, his greatest success as a trade union leader was when workers across the French West Africa went on a 71-days general strike to force the implementation of a new overseas labor code and was elected to Guinea's Territorial Assembly the same year. As a result, he was elected as one of the three secretaries-general of the French Communist Party's Confédération Générale du Travail (General Confederation of Labour; CGT) in 1954.[5]

In 1956 he organized the Union Générale des Travailleurs d'Afrique Noire, a common trade union centre for French West Africa. He was a leader of the RDA, working closely with Félix Houphouët-Boigny, who later was elected as president of the Ivory Coast. In 1956 Touré was elected Guinea's deputy to the French national assembly and mayor of Conakry, positions he used to criticize the French colonial regime.

Touré served for some time as a representative of African groups in France, where he worked to negotiate for the independence of France's African colonies.

In September 1958, Guinea participated in the referendum on the new French constitution. On acceptance of the new constitution, French overseas territories had the option of choosing to continue their existing status, to move toward full integration into metropolitan France, or to acquire the status of an autonomous republic in the new quasi-federal French Community. If, however, they rejected the new constitution, they would become independent forthwith. French President Charles de Gaulle made it clear that a country pursuing the independent course would no longer receive French economic and financial aid or retain French technical and administrative officers.

In 1958 Touré's Parti démocratique de Guinée, the RDA section in Guinea, pushed for a "No" in the French Union referendum sponsored by the French government. Guinea was the only one of France's African colonies to vote for immediate independence rather than continued association with France. Guinea became the only French colony to refuse to become part of the new French Community when it became independent in 1958. The electorate of Guinea rejected the new constitution overwhelmingly, and Guinea accordingly became an independent state on 2 October 1958, with Touré, leader of Guinea's strongest labor union, as president.

In the event, the rest of Francophone Africa gained independence two years later in 1960.

President of Guinea

.jpg)

In 1960, Touré declared his Parti démocratique de Guinée (PDG) to be the only legal party, though the country had effectively been a one-party state since independence. For the next 24 years, Touré effectively held all governing power in the nation. He was elected to a seven-year term as president in 1961; as leader of the PDG he was the only candidate. He was reelected unopposed in 1968, 1974 and 1982. Every five years, a single list of PDG candidates was returned to the National Assembly.

During his presidency, Touré's policies were strongly based on Marxism, with the nationalization of foreign companies and centralized economic plans. He won the Lenin Peace Prize as a result in 1961. Most of those actively opposed to his socialist regime were arrested and then jailed or exiled. His early actions to reject the French and then to appropriate wealth and farmland from traditional landlords angered many powerful forces, but the increasing failure of his government to provide either economic opportunities or democratic rights angered more.[6] While he is still revered in much of Africa[7] and in the Pan-African movement, many Guineans, and activists in Europe, have become critical of Touré's failure to institute meaningful democracy or free media.[8]

Opposition to single-party rule grew slowly, and by the late 1960s those who opposed his government faced the risk of detention camps and night visits by the secret police. His opponents often had two choices: say nothing or go abroad. From 1965 to 1975 Toure ended all his government's relations with France, the former colonial power.

Touré argued that Africa had lost much during colonization, and that Africa ought to retaliate by cutting off ties to former colonial nations. However, in 1978 Guinea's ties with the Soviet Union soured, and, as a sign of reconciliation, President of France Valéry Giscard d'Estaing visited Guinea, the first state visit by a French president.

Throughout Toure's dispute with France, he maintained good relations with several socialist countries. However, Touré's attitude toward France was not generally well received, and some African countries ended diplomatic relations with Guinea over his actions. Despite this, Touré's position won the support of many anti-colonialist and Pan-African groups and leaders.

Touré's primary allies in the region were presidents Kwame Nkrumah of Ghana and Modibo Keita of Mali. After Nkrumah was overthrown in a 1966 coup, Touré offered him asylum in Guinea and gave him the honorary title of co-president.[9] As a leader of the Pan-Africanist movement, Toure consistently spoke out against colonial powers, and befriended African American activists such as Malcolm X and Stokely Carmichael, to whom he offered asylum. The latter took the two leaders' names, as Kwame Ture.[10]

With Nkrumah, Toure helped in the formation of the All-African Peoples Revolutionary Party, and aided the PAIGC guerrillas in their fight against Portuguese colonialism in neighboring Portuguese Guinea. The Portuguese launched an attack upon Conakry in 1970 in order to rescue Portuguese prisoners of war, overthrow Touré's regime, and destroy PAIGC bases. They succeeded in the rescue but failed to dislodge Touré's regime.

Relations with the United States fluctuated during the course of Touré's reign. While Touré was not impressed with the Eisenhower administration's approach to Africa , he came to consider President John F. Kennedy a friend and an ally. He said that Kennedy was his "only true friend in the outside world". He was impressed by Kennedy's interest in African development and commitment to civil rights in the United States. Touré blamed Guinean labor unrest in 1962 on Soviet interference and turned to the United States as an ally.

His relations with Washington soured, however, after Kennedy's death. When a Guinean delegation was imprisoned in Ghana, after the overthrow of Nkrumah, Touré blamed Washington. He feared that the Central Intelligence Agency was plotting against his own regime.

During its first three decades of independence, Guinea developed into a militantly socialist state, which merged the functions and membership of the Parti Démocratique de Guinée (PDG) with the various institutions of government, including the public state bureaucracy. This unified party-state had nearly complete control over the country's economic and political life. Guinea expelled the US Peace Corps in 1966 because of their alleged involvement in a plot to overthrow President Touré. Similar charges were directed against France; diplomatic relations were severed in 1965 and Toure did not renew them until 1975. An ongoing source of contention between Guinea and its French-speaking neighbors was the estimated half-million expatriates in Senegal and Ivory Coast; some were active dissidents who, in 1966, formed the National Liberation Front of Guinea (Front de Libération Nationale de Guinée, or FLNG).

International tensions erupted again in 1970 when some 350 men, under the leadership of Portuguese officers from Portuguese Guinea (now Guinea-Bissau), including FLNG partisans and Africans-Portuguese soldiers, entered Guinea in order to rescue Portuguese prisoners detained in Conakry and capture Touré. Toure directed waves of arrests, detentions, and some executions of known and suspected opposition leaders in Guinea followed this military operation.

Between 1969 and 1976, according to Amnesty International, 4,000 persons on Guinea were detained for political reasons, with the fate of 2,900 unknown. After an alleged Fulani plot to assassinate Touré was disclosed in May 1976, Diallo Telli, a cabinet minister and formerly the first secretary-general of the OAU, was arrested and sent to prison. He died without trial in November of that year.

In 1977, protests against the regime's economic policy, which dealt harshly with unauthorized trading, led to riots in which three regional governors were killed. Touré responded by relaxing restrictions on trading, offering amnesty to exiles (thousands of whom returned), and releasing hundreds of political prisoners. Relations with the Soviet bloc grew cooler, as Touré sought to increase Western aid and private investment for Guinea's sagging economy.

Over time, Touré arrested large numbers of suspected political opponents and imprisoned them in camps, such as the notorious Camp Boiro National Guard Barracks. As a result of mass graves found in 2002, some 50,000 people are believed to have been killed under the regime of Touré in concentration camps such as Camp Boiro.[11][12][13][14][15]

Human Rights Watch in a 2007 report said that under Toure's regime, tens of thousands of Guinean dissidents sought refuge in exile, although this number is in dispute; some estimates are much higher.[16]

Once Guinea began its rapprochement with France in the late 1970s, Marxists among Toure's supporters began to oppose his government's shift toward capitalist liberalisation. In 1978, Toure formally renounced Marxism and reestablished trade with the West.[17]

Single-list elections for an expanded National Assembly were held in 1980. Touré was elected unopposed to a fourth seven-year term as president on 9 May 1982. A new constitution was adopted that month, and during the summer Touré visited the United States. It was part of his economic policy change that led him to seek Western investment in order to develop Guinea's huge mineral reserves. Measures announced in 1983 brought further economic liberalization, including the delegation of produce marketing to private traders.

Touré died on 26 March 1984 while undergoing cardiac treatment at the Cleveland Clinic in Cleveland, Ohio; he had been rushed to the United States after being stricken in Saudi Arabia the previous day. Touré's tomb is at the Camayanne Mausoleum, situated within the gardens of the Conakry Grand Mosque.

Prime Minister Louis Lansana Béavogui became acting president, pending elections that were to be held within 45 days.

The Political Bureau of the ruling Guinea Democratic Party was due to name its choice as Touré's successor on 3 April 1984. Under the constitution, the PDG's new leader would have been automatically elected to a seven-year term as president and confirmed in office by the voters by the end of spring. Just hours before that meeting took place, the armed forces seized power in a coup d'etat. They denounced the last years of Touré's rule as a "bloody and ruthless dictatorship." The constitution was suspended, the National Assembly dissolved, and the PDG abolished. Col. Lansana Conté, leader of the coup, assumed the presidency on 5 April, heading the Military Committee for National Recovery (Comité Militaire de Redressement National—CMRN). The military group freed about 1,000 political prisoners.

In 1985 Conté took advantage of an alleged coup attempt to arrest and execute several of Sekou Touré's close associates, including Ismael Touré, Seydou Keita, Siaka Touré, former commander of Camp Boiro; and Moussa Diakité.[18]

Works by Touré (partial)

- Ahmed Sékou Touré. 8 novembre 1964 (Conakry) : Parti démocratique de Guinée, (1965)

- A propos du Sahara Occidental : intervention du président Ahmed Sékou Touré devant le 17e sommet de l'OUA, Freetown, le 3 juillet 1980. (S.l. : s.n., 1980)

- Address of President Ahmed Sékou Touré, President of the Republic of Guinee (sic) : suggestions submitted during the West Africa consultative regional meeting held at Conakry, during 19 and 20 November 1971. (Cairo : Permanent Secretariat of the Afro-Asian Peoples' Solidarity Organization, 1971)

- Afrika and imperialism. Newark, N.J. : Jihad Pub. Co., 1973.

- Conférences, discours et rapports, Conakry : Impr. du Gouvernement, (1958-)

- Congres général de l'U.G.T.A.N. (Union général des travailleurs de l'Afrique noire) : Conakry, 15-18 janvier 1959 : rapport d'orientation et de doctrine. (Paris) : Présence africaine, c1959.

- Discours de Monsieur Sékou Touré, Président du Conseil de Gouvernement des 28 juillet et 25 aout 1958, de Monsieur Diallo Saifoulaye, Président de l'Assemblée territoriale et du Général de Gaulle, Président du Gouvernement de la Républ (Conakry) : Guinée Française, (1958)

- Doctrine and methods of the Democratic Party of Guinea (Conakry 1963).

- Expérience guinéenne et unité africaine. Paris, Présence africaine (1959)

- 'Guinée-Festival / commentaire et montage, Wolibo Dukuré dit Grand-pére. Conakry : Commission Culturelle du Comité Central, 1983.

- Guinée, prélude à l'indépendance (Avant-propos de Jacques Rabemananjara) Paris, Présence africaine (1958)

- Hommage à la révolution Cubaine ; Message du camarade Ahmed Sekou Toure au peuple Cubain à l'occasion du 20e anniversaire de l'attaque de la Caserne de Moncada (Juillet 1973). Conakry : Bureau de Presse de la Presidence de la Republique, (1975).

- Ahmed Sékou Touré. International policy and diplomatic action of the Democratic Party of Guinea; extracts from the report on doctrine and orientation submitted to the 3d National Conference of the P.D.G. (Cairo, Société Orientale de Publicité-Press, 1962)

- Ahmed Sékou Touré. Opening speech of the Summit of Heads of State and Government by President Ahmed Sékou Touré, chairman of the Summit (November 20, 1980). (S.l. : s.n., 1980)

- Ahmed Sékou Touré. Poèmes militants. (Conakry, Guinea) : Parti démocratique de Guinée, 1972

- Ahmed Sékou Touré. Political leader considered as the representative of a culture. (Newark, N. J. : Jihad Productions, 19--)

- Ahmed Sékou Touré. Pour l'amitié algéro-guinéenne. (Conakry, Guinea : Parti démocratique de Guinée, 1972)

- Rapport de doctrine et de politique générale, Conakry : Imprimerie Nationale, 1959.

- Strategy and tactics of the revolution, Conakry, Guinea : Press Office, 1978.

- Unité nationale, Conakry, République de Guinée (B.P. 1005, Conakry, République de Guinée) : Bureau de presse de la Présidence de la République, 1977.

See also

Notes

- ↑ "'Mass graves' found in Guinea". BBC News. October 22, 2002.

- ↑ RADIO-KANKAN: La premiere radio internet de Guinée-Conakry: GUINEE: RADIO-KANKAN

- ↑ Webster, James & Boahen, Adu (1980), The Revolutionary Years; West Africa since 1800, p. 324.

- ↑ Martin, G. (2012-12-23). African Political Thought. Springer. ISBN 9781137062055.

- ↑ Dictionary of African Biography. OUP USA. 2 February 2012. p. 49. ISBN 9780195382075.

- ↑ See: William Derman. Serfs, Peasants, and Socialists: A Former Serf Village in the Republic of Guinea, University of California Press (1968, 2nd ed 1973). ISBN 978-0-520-01728-3

- ↑ As one example see the text of a posthumous award given to Touré by the South African presidency Archived 2008-04-14 at the Wayback Machine..

- ↑

- ↑ Webster, James & Boahen, Adu (1980), The Revolutionary Years; West Africa since 1800, p. 377.

- ↑ See Molefi K. Asante, Ama Mazama. Encyclopedia of Black Studies. pp78-80

- ↑ "'Mass graves' found in Guinea". BBC News. October 22, 2002.

- ↑ "Camp Boiro". Retrieved 10 February 2015.

- ↑ "RFI - Les victimes du camp Boiro empêchées de manifester". Retrieved 10 February 2015.

- ↑ "From military politization to militarization of power in Guinea-Conakry". Journal of Political and Military Sociology. 2000.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2012-07-25. Retrieved 2008-12-26.

- ↑ Guinea Background note, Human Rights Watch, 2007. Numbers fleeing remain controversial. Anti-Toure activists and the United States government say a million fled, HRW say tens of thousands.

For the memorial to victims of Toure's government, see: campboiro.org/ For their view, reflected in the Statues of the Camp Boiro International Memorial (CBIM), see : Tierno S. Bah: Camp Boiro International Memorial Archived 2008-03-06 at the Wayback Machine.. Quote: "At its peak, Camp Boiro was a contemporary of the Khmer Rouge and a precursor of the Rwandan genocides." - ↑ https://books.google.com/books?id=xbmCBAAAQBAJ&pg=PR54

- ↑ André Lewin (2009). "20 à 30, le député français Sékou Touré conduit la Guinée à l'indépendance, et séduit en premier les pays communistes". Ahmed Sékou Touré, 1922-1924: président de la Guinée de 1958 à 1984. 1956-1958 (in French). Editions L'Harmattan. p. 27. ISBN 2-296-09528-3.

References

- Henry Louis Gates, Anthony Appiah (eds). Africana: The Encyclopedia of the African and African, "Ahmed Sékou Touré," pp1857–58. Basic Civitas Books (1999). ISBN 0-465-00071-1

- Molefi K. Asante, Ama Mazama. Encyclopedia of Black Studies. Sage Publications (2005) ISBN 0-7619-2762-X

- (in French) Ibrahima Baba Kake. Sékou Touré. Le Héros et le Tyran. Paris, 1987, JA Presses. Collection Jeune Afrique Livres. 254 p

- Lansiné Kaba. "From Colonialism to Autocracy: Guinea under Sékou Touré, 1957–1984;" in Decolonization and African Independence, the Transfers of Power, 1960-1980. Prosser Gifford and William Roger Louis (eds). New Haven: Yale University Press, 1988.

- Phineas Malinga. "Ahmed Sékou Touré: An African Tragedy"

- Baruch Hirson. "The Misdirection of C.L.R. James", Communalism and Socialism in Africa, 1989.

- John Leslie. Towards an African socialism, International Socialism (1st series), No.1, Spring 1960, pp. 15–19.

- (in French) Alpha Mohamed Sow, "Conflits ethnique dans un État révolutionnaire (Le cas Guinéen)", in Les ethnies ont une histoire, Jean-Pierre Chrétien, Gérard Prunier (ed), pp. 386–405, KARTHALA Editions (2003) ISBN 2-84586-389-6

- Parts of this article were translated from French Wikipedia's fr:Ahmed Sékou Touré.

News articles

- "New West Africa Union Sealed By Heads of Ghana and Guinea" By THOMAS F. BRADY, The New York Times. May 2, 1959, p. 2

- GUINEA SHUNS TIE TO WORLD BLOCS; But New State Gets Most Aid From East—Toure Departs for a Visit to the U. S. By JOHN B. OAKES, The New York Times, October 25, 1959, p. 16,

- Red Aid to Guinea Rises By HOMER BIGART, The New York Times. March 6, 1960, p. 4

- HENRY TANNER. REGIME IN GUINEA SEIZES 2 UTILITIES; Toure Nationalizes Power and Water Supply Concerns—Pledges Compensation, The New York Times. February 2, 1961, Thursday, p. 3

- TOURE SAYS REDS PLOTTED A COUP; Links Communists to Riots by Students Last Month. (UPI), The New York Times. December 13, 1961, Wednesday, p. 14

- Toure's Country--'Africa Incarnate'; Gui'nea embodies the emphatic nationalism and revolutionary hopes of ex-colonial Africa, but its energetic President confronts handicaps that are also typically African. Toure's Country--'Africa Incarnate' By David Halberstam, July 8, 1962, Sunday The New York Times Magazine, p. 146

- GUINEA RELAXES BUSINESS CURBS; Turns to Free Enterprise to Rescue Economy. (Reuters), The New York Times, December 8, 1963, Sunday p. 24

- U.S. PEACE CORPS OUSTED BY GUINEA; 72 Members and Dependents to Leave Within a Week By RICHARD EDER, The New York Times, November 9, 1966, Wednesday, p. 11

- Guinea Is Warming West African Ties, The New York Times, January 26, 1968, Friday, p. 52

- ALFRED FRIENDLY Jr. TOURE ADOPTING A MODERATE TONE; But West Africa Is Skeptical of Guinean's Words. The New York Times. April 28, 1968, Sunday, p. 13

- Ebb of African 'Revolution', The New York Times, December 7, 1968, Saturday p. 46

- Guinea's President Charges A Plot to Overthrow Him, (Agence France-Presse), The New York Times, January 16, 1969, Thursday p. 10

- Guinea Reports 2 Members Of Cabinet Seized in Plot, (Reuters), The New York Times, March 22, 1969, Saturday p. 14

- 12 FOES OF REGIME DOOMED IN GUINEA, The New York Times, May 16, 1969, Friday p. 2

- Guinea Reports Invasion From Sea by Portuguese; Lisbon Denies Charge U.N. Council Calls for End to Attack Guinea Reports an Invasion From Sea (Associated Press), The New York Times, November 23, 1970, Monday, p. 1

- Guinea: Attack Strengthens Country's Symbolic Role, The New York Times, November 29, 1970, Sunday, p. 194

- GUINEAN IS ADAMANT ON DEATH SENTENCES, The New York Times, January 29, 1971, Friday. p. 3

- Guinea Wooing the West In Bauxite Development; GUINEA IS SEEKING HELP ON BAUXITE, The New York Times, February 15, 1971, Monday Section: BUSINESS AND FINANCE, p. 34

- Political Ferment Hurts Guinea, The New York Times, January 31, 1972, Monday Section: SURVEY OF AFRICA'S ECONOMY, p. 46

- GUINEAN, IN TOTAL REVERSAL, ASKS MORE U.S. INVESTMENT By BERNARD WEINRAUB, The New York Times]], July 2, 1982, Friday Late City Final Edition, p. A3, Col. 5

- GUINEA IS SLOWLY BREAKING OUT OF ITS TIGHT COCOON By ALAN COWELL, The New York Times, December 3, 1982, Friday, Late City Final Edition, p. A2, Col. 3

- IN REVOLUTIONARY GUINEA, SOME OF THE FIRE IS GONE By ALAN COWELL, The New York Times, December 9, 1982, Thursday, Late City Final Edition, p. A2, Col. 3

- GUINEA'S PRESIDENT, SEKOU TOURE, DIES IN CLEVELAND CLINIC By CLIFFORD D. MAY, The New York Times, Obituary, March 28, 1984, Wednesday, Late City Final Edition, p. A1, Col. 1

- THOUSANDS MOURN DEATH OF TOURE By CLIFFORD D. MAY, The New York Times, March 29, 1984, Thursday, Late City Final Edition, p. A3, Col. 1

- AHMED SEKOU TOURE, A RADICAL HERO By ERIC PACE, The New York Times, Obituary, March 28, 1984, Wednesday, Late City Final Edition, p. A6, Col. 1

- IN POST-COUP GUINEA, A JAIL IS THROWN OPEN. CLIFFORD D. MAY. The New York Times, April 12, 1984, Thursday, Late City Final Edition, p.A1, Col. 4

- TOPICS; HOW TO RUN THINGS, OR RUIN THEM, The New York Times, March 29, 1984.

- Guinea Airport Opens; Capital Appears Calm, The New York Times, April 7, 1984.

- Guinea Frees Toure's Widow, (Reuters), The New York Times, January 3, 1988.

- How France Shaped New Africa, HOWARD W. FRENCH, The New York Times, February 28, 1995.

- Conversations/Kwame Ture; Formerly Stokely Carmichael And Still Ready for the Revolution, KAREN DE WITT, The New York Times, April 14, 1996.

- Stokely Carmichael, Rights Leader Who Coined 'Black Power,' Dies at 57, MICHAEL T. KAUFMAN, The New York Times, November 16, 1998.

- 'Mass graves' found in Guinea. BBC, 22 October 2002.

- Stokely Speaks (Book Review), ROBERT WEISBROT, The New York Times Review of Books, November 23, 2003.

Other secondary works

- Graeme Counsel. "Popular music and politics in Sékou Touré’s Guinea". Australasian Review of African Studies. 26 (1), pp. 26-42. 2004

- Jean-Paul Alata. Prison d'Afrique

- Jean-Paul Alata. Interview-témoignage de Jean-Paul Alata sur Radio-France Internationale

- Herve Hamon, Patrick Rotman L'affaire Alata

- Ladipo Adamolekun. "Sekou Toure's Guinea: An Experiment in Nation Building". Methuen (August 1976). ISBN 0-416-77840-2

- Koumandian Kéita. Guinée 61: L'École et la Dictature. Nubia (1984).

- Ibrahima Baba Kaké. Sékou Touré, le héros et le tyran. Jeune Afrique, Paris (1987)

- Alpha Abdoulaye Diallo. La vérité du ministre: Dix ans dans les geôles de Sékou Touré. (Questions d'actualité), Calmann-Lévy, Paris (1985). ISBN 978-2-7021-1390-5

- Kaba Camara 41. Dans la Guinée de Sékou Touré : cela a bien eu lieu.

- Kindo Touré. Unique survivant du Complot Kaman-Fodéba

- Adolf Marx. Maudits soient ceux qui nous oublient.

- Ousmane Ardo Bâ. Camp Boiro. Sinistre geôle de Sékou Touré. Harmattan, Paris (1986) ISBN 978-2-85802-649-4

- Mahmoud Bah. Construire la Guinée après Sékou Touré

- Mgr. Raymond-Marie Tchidimbo. Noviciat d'un évêque : huit ans et huit mois de captivité sous Sékou Touré.

- Amadou Diallo. La mort de Telli Diallo

- Almamy Fodé Sylla. L'Itinéraire sanglant

- Comité Telli Diallo. J'ai vu : on tue des innocents en Guinée-Conakry

- Alsény René Gomez. Parler ou périr

- Sako Kondé. Guinée. Le temps des fripouilles

- André Lewin. Diallo Telli. Le Destin tragique d'un grand Africain.

- Camara Laye. Dramouss

- Dr. Thierno Bah. Mon combat pour la Guinée

- Nadine Bari. Grain de sable

- Nadine Bari. Noces d'absence

- Nadine Bari. Chroniques de Guinée (1994)

- Nadine Bari. Guinée. Les cailloux de la mémoire (2004)

- Maurice Jeanjean. Nadine Bari. Sékou Touré, Un totalitarisme africain

- Collectif Jeune Afrique. Sékou Touré. Ce qu'il fut. Ce qu'il a fait. Ce qu'il faut défaire.

- Claude Abou Diakité. La Guinée enchaînée

- Alpha Condé. Guinée, néo-colonie américaine ou Albanie d'Afrique

- Lansiné Kaba. From colonialism to autocracy. Guinea under Sékou Touré: 1957-1984

- Charles E. Sory. Sékou Touré, l'ange exterminateur

- Charles Diané. Sékou Touré, l'homme et son régime : lettre ouverte au président Mitterrand

- Emile Tompapa. Sékou Touré : quarante ans de dictature

- Alpha Ousmane Barry. Pouvoir du discours et discours du pouvoir : l'art oratoire chez Sékou Touré de 1958 à 1984

External links

- 1959 Time Magazine cover story about Sékou Touré

- WebGuinee - Sekou Toure Publishes full text of books and articles as well photos of Sekou Toure

- Camp Boiro Memorial. Extensive list of reports and articles on the notorious political prison where thousands of victims of the dictatorship of Sekou Toure disappeared between 1960 and 1984.

- More information about Ahmed Sékou Touré (French)

- BBC Radio: President Sekou Toure Defends One-Party Rule (1959).

- Conflict history: Guinea, 11 May 2007. International Crisis Group.

- 1st page on the French National Assembly website

- 2nd page on the French National Assembly website

| Political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Position created |

President of Guinea 1958–1984 |

Succeeded by Louis Lansana Beavogui (interim) |