Secularism in Turkey

.jpg)

Religion in Turkey  |

|---|

| Secularism in Turkey |

|

Minor religions |

| Irreligion in Turkey |

Secularism in Turkey defines the relationship between religion and state in the country of Turkey. Secularism (or laïcité) was first introduced with the 1928 amendment of the Constitution of 1924, which removed the provision declaring that the "Religion of the State is Islam", and with the later reforms of Turkey's first president Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, which set the administrative and political requirements to create a modern, democratic, secular state, aligned with Kemalism.

Nine years after its introduction, laïcité was explicitly stated in the second article of the then Turkish constitution on February 5, 1937. The current Constitution of 1982 neither recognizes an official religion nor promotes any. This includes Islam, to which more than 99% of its citizens subscribe.[1]

Turkey's "laïcité" calls for the separation of religion and the state, but also describes the state's stance as one of "active neutrality". Turkey's actions related with religion are carefully analyzed and evaluated through the Presidency of Religious Affairs (Diyanet İşleri Başkanlığı or simply Diyanet). The duties of the Presidency of Religious Affairs are "to execute the works concerning the beliefs, worship, and ethics of Islam, enlighten the public about their religion, and administer the sacred worshipping places".[2]

History

The history of secularism in Turkey extends to the Tanzimat reforms of Ottoman Empire. The second peak in secularism occurred during the Second Constitutional Era. The current form was achieved by Atatürk's Reforms.

Ottoman Empire

The establishing structure (Ruling institution of the Ottoman Empire) of the Ottoman Empire (13th century) was an Islamic state in which the head of the Ottoman state was the Sultan. The social system was organized around millet. Millet structure allowed a great degree of religious, cultural and ethnic continuity to non-Muslim populations across the subdivisions of the Ottoman Empire and at the same time it permitted their incorporation into the Ottoman administrative, economic and political system.[3] The Ottoman-appointed governor collected taxes and provided security, while the local religious or cultural matters were left to the regional communities to decide. On the other hand, the sultans were Muslims and the laws that bound them were based on the Sharia, the body of Islamic law, as well as various cultural customs. The Sultan, beginning in 1516, was also a Caliph, the leader of all the Sunni Muslims in the world. By the turn of the 19th century the Ottoman ruling elite recognized the need to restructure the legislative, military and judiciary systems to cope with their new political rivals in Europe. When the millet system started to lose its efficiency due to the rise of nationalism within its borders, the Ottoman Empire explored new ways of governing its territory composed of diverse populations.

Sultan Selim III founded the first secular military schools by establishing the new military unit, Nizam-ı Cedid, as early as 1792. However the last century (19th century) of the Ottoman Empire had many far reaching reforms. These reforms peaked with the tanzimat which was the initial reform era of the Ottoman Empire. After the tanzimat, rules, such as those relating to the equalized status of non-Muslim citizens, the establishment of a parliament, the abandonment of medieval punishments for apostasy,[4] as well as the codification of the constitution of the empire and the rights of Ottoman subjects were established. The First World War brought about the fall of the Ottoman Empire and the subsequent partitioning of the Ottoman Empire by the victorious Allies. Therefore, the Republic of Turkey was actually a nation-state built as a result of an empire lost.

Reforms of Republic

During the establishment of the Republic, there were two sections of the elite group at the helm of the discussions for the future. These were the Islamist reformists and Westerners.[3] They shared a similar goal, the modernization of the new state. Many basic goals were common to both groups. The founder of the modern Turkish Republic Mustafa Kemal Atatürk's achievement was to amplify this common ground and put the country on a fast track of reforms, now known as Atatürk's Reforms.

Their first act was to give the Turkish nation the right to exercise popular sovereignty via representative democracy. Prior to declaring the new Republic, the Turkish Grand National Assembly abolished the constitutional monarchy on November 1, 1922. The Turkish Grand National Assembly then moved to replace the extant Islamic law structure with the laws it had passed during the Turkish War of Independence, beginning in 1919. The modernization of the Law had already begun at the point that the project was undertaken in earnest. A milestone in this process was the passage of the Turkish Constitution of 1921. Upon the establishment of the Republic on October 29, 1923, the institution of the Caliphate remained, but the passage of a new constitution in 1924 effectively abolished this title held by the Ottoman Sultanate since 1517. Even as the new constitution eliminated the Caliphate it, at the same time, declared Islam as the official religion of the Turkish Republic. The Caliphate's powers within Turkey were transferred to the National Assembly and the title has since been inactive. The Turkish Republic does in theory still retain the right to reinstate the Caliphate, should it ever elect to do so.

Following quickly upon these developments, a number of social reforms were undertaken. Many of these reforms affected every aspect of Turkish life, moving to erase the legacy of dominance long held by religion and tradition. The unification of education, installation of a secular education system, and the closure of many religious orders took place on March 3, 1924. This extended to closure of religious convents and dervish lodges on November 30, 1925. These reforms also included the extension to women of voting rights in 1931 and the right be to elected to public office on December 5, 1934. The inclusion of reference to laïcité into the constitution was achieved by an amendment on February 5, 1937, a move regarded as the final act in the project of instituting complete separation between governmental and religious affairs in Turkey.

AKP political agenda of Islamization

According to at least one observer (Mustafa Akyol), under the Islamic Justice and Development Party (AKP) government of President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, starting in 2007, "hundreds of secularist officers and their civilian allies" were jailed, and by 2012 the "old secularist guard" in positions of authority was replaced by members/supporters of the AKP party and the Islamic Gülen movement.[5] On 25 April 2016, the Turkish Parliament Speaker İsmail Kahraman told a conference of Islamic scholars and writers in Istanbul that "secularism would not have a place in a new constitution”, as Turkey is “a Muslim country and so we should have a religious constitution". (One of the duties of Parliament Speaker is to pen a new draft constitution for Turkey.)[6]

Some have also complained (see cite) that under Erdoğan, the old role of the Diyanet—maintaining control over the religious sphere of Islam in Turkey—has "largely been turned on its head".[7] Now greatly increased in size, the Diyanet promotes a certain type of conservative (Hanafi Sunni) Islam inside Turkey, issuing fatawa forbidding such activities as "feeding dogs at home, celebrating the western New Year, lotteries, and tattoos";[8] and projecting this "Turkish Islam"[7] abroad.[9]

The government of Recep Tayyip Erdoğan and the Justice and Development Party (AKP) pursue the explicit policy agenda of Islamization of education to "raise a devout generation" against secular resistance,[10][11] in the process causing lost jobs and school for many non-religious citizens of Turkey.[12] Following the July Coup, which President Erdoğan called “a gift from God",[13] thousands were purged by the Justice and Development Party (AKP) government—primarily followers of the Gülen movement, which is alleged to have launched the coup—but also remaining secularists.[14] One explanation for the end of secularism in Turkey is that socialism was seen as a threat from the left to "capitalist supremacy", and Islamic values were restored in the education system because they "appeared best suited to neutralize any challenges from the left to capitalist supremacy."[15]

Constitutional principles

The Constitution asserts that Turkey (used to be / is supposed to be) a secular and democratic republic, deriving its sovereignty from the people. The sovereignty rests with the Turkish Nation, who delegates its exercise to an elected unicameral parliament, the Turkish Grand National Assembly. Moreover, Article 4: declares the immovability the founding principles of the Republic defined in the first three Articles:

- "secularism, social equality, equality before the law"

- "the Republican form of government"

- "the indivisibility of the Republic and of the Turkish Nation",

The Constitution bans any proposals for the modification of these articles. Each of these concepts which were distributed in the three articles of the constitution can not be achieved without the other two concepts. The constitution requires a central administration which would lose its meaning (effectiveness, coverage, etc.) if the system is not based on laïcité, social equality, and equality before law. Vice versa, if the Republic differentiate itself based on social, religious differences, administration can not be equal to the population when the administration is central. The system which tried to be established in the constitution sets out to found a unitary nation-state based on the principles of secular democracy.

Impact on society

The Turkish Constitution recognizes freedom of religion for individuals whereas identified religious communities are placed under the protection of state, but the constitution explicitly states that they cannot become involved in the political process (by forming a religious party for instance) and no party can claim that it represents a form of religious belief. Nevertheless, religious views are generally expressed through conservative parties.

In recent history, two parties have been ordered to close (Welfare Party [Turkish: Refah Partisi)] in 1998, and Virtue Party [(Turkish: Fazilet Partisi)] in 2001) by the Constitutional Court for Islamist activities and attempts to "redefine the secular nature of the republic". The first party to be closed for suspected anti-secularist activities was the Progressive Republican Party on June 3, 1925.

The current governing party in Turkey, the conservative Justice and Development Party (Turkish: Adalet ve Kalkınma Partisi or AKP), has often been accused of following an Islamist agenda.

Issues relating to Turkey's secularism were discussed in the lead up to the 2007 presidential elections, in which the ruling party chose a candidate with Islamic connections, Abdullah Gül, for the first time in its secular republic. While some in Turkey have expressed concern that the nomination could represent a move away from Turkey's secularist traditions, including particularly Turkey's priority on equality between the sexes, others have suggested that the conservative party has effectively promoted modernization while reaching out to more traditional and religious elements in Turkish society.[16][17] On July 22, 2007 it was reported that the more religiously conservative ruling party won a larger than expected electoral victory in the parliamentary elections.[18]

Turkey's preservation and maintenance of its secular identity has been a profound issue and source of tension. Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan has broken with secular tradition, by speaking out in favor of limited Islamism and against the active restrictions, instituted by Atatürk on wearing the Islamic-style head scarves in government offices and schools. The Republic Protests (Turkish: Cumhuriyet Mitingleri) were a series of peaceful mass rallies that took place in Turkey in the spring of 2007 in support of the Kemalist ideals of state secularism.[19]

The constitutional rule that prohibits discrimination on religious grounds is taken very seriously. Turkey, as a secular country, prohibits by law the wearing of religious headcover and theo-political symbolic garments for both genders in government buildings and schools;[20] a law upheld by the Grand Chamber of the European Court of Human Rights as legitimate on November 10, 2005 in Leyla Şahin v. Turkey.[21]

The strict application of secularism in Turkey has been credited for enabling women to have access to greater opportunities, compared to countries with a greater influence of religion in public affairs, in matters of education, employment, wealth as well as political, social and cultural freedoms.[22]

Also paradoxical with the Turkish secularism is the fact that identity document cards of Turkish citizens include the specification of the card holder's religion.[23] This declaration was perceived by some as representing a form of the state's surveillance over its citizens' religious choices.

The mainstream Hanafite school of Sunni Islam is entirely organized by the state, through the Diyanet İşleri Başkanlığı (Religious Affairs Directorate), which supervises all mosques, educates the imams who work in them, and approves all content for religious services and prayers. It appoints imams, who are classified as civil servants.[24] This micromanagement of Sunni religious practices, at times, seems much more sectarian than secular, as it violates the principle of state neutrality in religious practice. Groups that have expressed dissatisfaction with this situation include a variety of non-governmental Sunni / Hanafi groups (such as the Nurci movement), whose interpretation of Islam tends to be more activist; and the non-Sunni Alevi lik, whose members tend to resent supporting the Sunni establishment with their tax money (whereas the Turkish state does not subsidize Alevi religious activities).

Criticism

Critics argue that the Turkish state's support for and regulation of Sunni religious institutions – including mandatory religious education for children deemed by the state to be Muslims – amount to de facto violations of secularism. Debate arises over the issue of to what degree religious observance ought to be restricted to the private sphere – most famously in connection with the issues of head-scarves and religious-based political parties (cf. Welfare Party, AKP). The issue of an independent Greek Orthodox seminary is also a matter of controversy in regard to Turkey's accession to the European Union, the reason being that it makes no sense for Turkey to completely oppress a small theological education center when it funds thousands more. Also the fact that only Sunni Muslims receive state salaries when working as appointed clergy is another issue being criticised.

Reforms going in the direction of secularism have been completed under Atatürk (abolition of the Caliphate, etc.).

However, Turkey is not strictly a secular state:

- there is no separation between religion and State

- there is a tutelage of religion by the state

Religion is mentioned on the identity documents and there is an administration called "Presidency of Religious Affairs" or Diyanet[25] which exploits Islam to legitimize sometimes State and manages 77,500 mosques. This state agency, established by Ataturk in 1924, and which had a budget over U.S. $2.5 billion in 2012 finances only Sunni Muslim worship. Other religions must ensure a financially self-sustaining running and they face administrative obstacles during operation.[26]

When harvesting tax, all Turkish citizens are equal. The tax rate is not based on religion. However, through the Diyanet, Turkish citizens are not equal in the use of revenue. For example, Câferî Muslims (mostly Azeris) and Alevi Bektashi (mostly Turkmen) participate in the financing of the mosques and the salaries of Sunni imams, while their places of worship, which are not officially recognized by the State, don't receive any funding.

Theoretically, Turkey, through the Treaty of Lausanne (1923), recognizes the civil, political and cultural rights of non-Muslim minorities.

In practice, Turkey only recognizes Greek, Armenian and Jewish religious minorities without granting them all the rights mentioned in the Treaty of Lausanne.

Alevi Bektashi Câferî Muslims,[27] Latin Catholics and Protestants are not recognized officially.

| Religions | Estimated population | Expropriation measures [28] |

Official recognition through the Constitution or international treaties | Government Financing of places of worship and religious staff |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Islam - Sunnite | 70 to 85% (52 to 64 millions) | No | Yes through the Diyanet mentioned in the Constitution (art.136) [29] | Yes through the Diyanet [30] |

| Twelver Islam - Bektasi | 15 to 25% (11 to 19 millions) | Yes [27] | No. In 1826 with the abolition of the Janissary corps, the Bektashi tekke (dervish convent) were closed [27][31] · [32] | No [30] |

| Twelver Islam - Alevi | No.[32] In the early fifteenth century,[33] due to the unsustainable Ottoman oppression, Alevi supported Shah Ismail I. who had Turkmen origins. Shah Ismail I. supporters, who wear a red cap with twelve folds in reference to the 12 Imams were called Qizilbash. Ottomans who were Arabized and persanised considered Qizilbash (Alevi) as enemies because of their Turkmen origins.[33] Today, cemevi, places of worship of Alevi Bektashi have no official recognition. | |||

| Twelver Islam - Câferî | 4% (3 millions) [34] | No [32] | No [30] | |

| Twelver Islam - Alawite | 300 to 350 000 [35] | No [32] | No [30] | |

| Judaism | 20,000 | Yes [28] | Yes through the Treaty of Lausanne (1923)[32] | No [30] |

| Christian - Protestant | 5,000 | No [32] | No [30] | |

| Christian – Latin Catholics | 35,000[36] |

No [32] | No [30] | |

| Christian – Greek Catholics | Yes [28] | Yes through the Treaty of Lausanne (1923)[32] | No [30] | |

| Christian - Orthodox - Greek (Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople) | 3,000-4,000[37] | Yes [28] | Yes through the Treaty of Lausanne (1923)[32] | No [30] |

| Christian - Orthodox - Antiochian Orthodox (Greek Orthodox Church of Antioch) | 18,000[38][39] | No[32] | No [30] | |

| Christian - Orthodox - Armenian (Armenian Patriarchate of Constantinople) | 57,000-80,000[40][41] | Yes [28] | Yes through the Treaty of Lausanne (1923)[32] | No [30] |

| Christian - Catholics Chaldean Christians (Armenian) | 3,000 | Yes [28] | Yes through the Treaty of Lausanne (1923)[32] | No [30] |

| Christian - Syriac Orthodox and Catholic Churches | 15,000 | Yes [28] | No [32] | No [30] |

| Yazidi | 377 | No [32] | No [30] |

With more than 100,000 employees, the Diyanet is a kind of state within the state.[42]

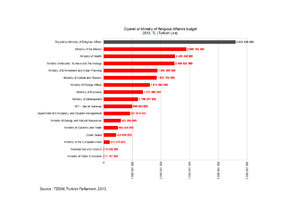

In 2013, with over 4.6 billion TL (Turkish Lira), Diyanet or Ministry of Religious Affairs, occupies the 16th position of central government expenditure.

The budget allocated to Diyanet is:

- 1.6 times larger than the budget allocated to the Ministry of the Interior[43]

- 1.8 times larger than the budget allocated to the Ministry of Health[43]

- 1.9 times larger than the budget allocated to the Ministry of Industry, Science and Technology[43]

- 2.4 times larger than the budget allocated to the Ministry of Environment and Urban Planning[43]

- 2.5 times larger than the budget allocated to the Ministry of Culture and Tourism[43]

- 2.9 times larger than the budget allocated to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs[43]

- 3.4 times larger than the budget allocated to the Ministry of Economy[43]

- 3.8 times larger than the budget of the Ministry of Development[43]

- 4.6 times larger than the budget allocated to MIT – Secret Services [43]

- 5,0 times larger than the budget allocated to the Department of Emergency and Disaster Management[43]

- 7.7 times larger than the budget allocated to the Ministry of Energy and Natural Resources[43]

- 9.1 times larger than the budget allocated to the Ministry of Customs and Trade[43]

- 10.7 times greater than the budget allocated to Coast Guard[43]

- 21.6 times greater than the budget allocated to the Ministry of the European Union[43]

- 242 times larger than the budget for the National Security Council[43]

- 268 times more important than the budget allocated to the Ministry of Public Employee[43]

Diyanet's budget represents:

- 79% of the budget of the Police[43]

- 67% of the budget of the Ministry of Justice[43]

- 57% of the budget of the Public Hospitals[43]

- 31% of the budget of the National Police[43]

- 23% of the budget of the Turkish Army (NATO's second largest standing army)[43]

Headscarf controversy

Many of the passages citations can be found at the UNHCR[44]

With a policy of official secularism, the Turkish government has traditionally banned the wearing of headscarves by women who work in the public sector. The ban applies to teachers, lawyers, parliamentarians and others working on state premises. The ban on headscarves in the civil service and educational and political institutions was expanded to cover non-state institutions. Authorities began to enforce the headscarf ban among mothers accompanying their children to school events or public swimming pools, while female lawyers and journalists who refused to comply with the ban were expelled from public buildings such as courtrooms and universities . In 1999, the ban on headscarves in the public sphere hit the headlines when Merve Kavakçı, a newly elected MP for the Virtue Party was prevented from taking her oath in the National Assembly because she wore a headscarf. The constitutional rule that prohibits discrimination on religious grounds is taken very seriously. Turkey, as a secular country, prohibits by law the wearing of religious headcover and theo-political symbolic garments for both genders in government buildings, schools, and universities;[20] a law upheld by the Grand Chamber of the European Court of Human Rights as legitimate on November 10, 2005 in Leyla Şahin v. Turkey.[21]

Workplace

According to Country Reports 2007, women who wore headscarves and their supporters "were disciplined or lost their jobs in the public sector" (US 11 March 2008, Sec. 2.c). Human Rights Watch (HRW) reports that in late 2005, the Administrative Supreme Court ruled that a teacher was not eligible for a promotion in her school because she wore a headscarf outside of work (Jan. 2007). An immigration counsellor at the Embassy of Canada in Ankara stated in 27 April 2005 correspondence with the Research Directorate that public servants are not permitted to wear a headscarf while on duty, but headscarved women may be employed in the private sector. In 12 April 2005 correspondence sent to the Research Directorate, a professor of political science specializing in women's issues in Turkey at Bogazici University in Istanbul indicated that women who wear a headscarf "could possibly be denied employment in private or government sectors." Conversely, some municipalities with a more traditional constituency might attempt to hire specifically those women who wear a headscarf (Professor 12 April 2005). The professor did add, however, that headscarved women generally experience difficulty in obtaining positions as teachers, judges, lawyers, or doctors in the public service (ibid.). More recent or corroborating information on the headscarf ban in the public service could not be found among the sources consulted by the Research Directorate.

The London-based Sunday Times reports that while the ban is officially in place only in the public sphere, many private firms similarly avoid hiring women who wear headscarves (6 May 2007). MERO notes that women who wear headscarves may have more difficulty finding a job or obtaining a desirable wage (Apr. 2008), although this could not be corroborated among the sources consulted by the Research Directorate.

Medical care

According to the Sunday Times, headscarves are banned inside Turkish hospitals, and doctors may not don a headscarf on the job (6 May 2007). Nevertheless, MERO reports that under Turkey's current administration, seen by secularists to have a hidden religious agenda (The New York Times 19 February 2008; Washington Post 26 February 2008), doctors who wear headscarves have been employed in some public hospitals (MERO Apr. 2008).

Ban lifted

On 9 February 2008, Turkey's parliament approved a constitutional amendment that lifted the ban on Islamic headscarves in universities. Prior to this date, the public ban on headscarves officially extended to students on university campuses throughout Turkey. Nevertheless, according to Country Reports on Human Rights Practices for 2007, "some faculty members permitted students to wear head coverings in class". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty notes that since the 1990s, some rectors have allowed students to wear headscarves.

On 5 June 2008, Turkey's Constitutional Court annulled the parliament's proposed amendment intended to lift the headscarf ban, ruling that removing the ban would run counter to official secularism. While the highest court's decision to uphold the headscarf ban cannot be appealed (AP 7 June 2008), the government has nevertheless indicated that it is considering adopting measures to weaken the court's authority.

Wearing of head-covering

According to the Turkish Economic and Social Studies Foundation around 62% of women wear the headscarf in Turkey.[45][46][47]

Turkey’s strong secularism has resulted in what have been perceived by some as strictures on the freedom of religion; for example, the headscarf has long been prohibited in public universities, and a constitutional amendment passed in February 2008 that permitted women to wear it on university campuses sparked considerable controversy. In addition, the armed forces have maintained a vigilant watch over Turkey’s political secularism, which they affirm to be a keystone among Turkey’s founding principles. The military has not left the maintenance of a secular political process to chance, however, and has intervened in politics on a number of occasions.[48]

See also

References

- ↑ "Turkey". The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency (US). 2008-07-24. Retrieved 2008-08-01.

- ↑ Basic Principles, Aims And Objectives, Presidency of Religious Affairs

- 1 2 "Secularism: The Turkish Experience" (PDF). Retrieved 2013-09-28.

- ↑ Hussain, Ishtiaq (2011-10-07). "The Tanzimat: Secular Reforms in the Ottoman Empire" (PDF). Faith Matters. Retrieved 2013-09-28.

- ↑ Akyol, Mustafa (July 22, 2016). "Who Was Behind the Coup Attempt in Turkey?". New York Times. Retrieved 23 July 2016.

- ↑ "‘We are a Muslim country’: Turkey’s parliament speaker advocates religious constitution". RT. 26 April 2016. Retrieved 25 July 2016.

- 1 2 Lepeska, David (17 May 2015). "Turkey Casts the Diyanet". Foreign Affairs. Retrieved 27 July 2016.

- ↑ Cornell, Svante (2015-10-09). "The Rise of Diyanet: the Politicization of Turkey’s Directorate of Religious Affairs". turkeyanalyst.org. Retrieved 2016-07-27.

- ↑ Tremblay, Pinar (April 29, 2015). "Is Erdogan signaling end of secularism in Turkey?". Al Monitor. Retrieved 25 July 2016.

- ↑ Sukru Kucuksahin (20 June 2016). "Turkish students up in arms over Islamization of education". Al-Monitor.

- ↑ Zülfikar Doğan (29 June 2016). "Erdogan pens education plan for Turkey's 'devout generation'". Al-Monitor.

- ↑ Sibel Hurtas (13 October 2016). "Turkey’s 'devout generation' project means lost jobs, schools for many". Al-Monitor.

- ↑ "Coup Was ‘Gift From God’ for Erdogan Planning a New Turkey". Bloomberg.com. 2016-07-17. Retrieved 2017-01-09.

- ↑ "Leftists, Kemalists suspended from posts for being Gülenists, says CHP report | Turkey Purge". turkeypurge.com. Retrieved 2017-01-09.

- ↑ "Turkey’s journey from secularism to Islamization: A capitalist story". Your Middle East. May 23, 2016. Retrieved 2017-01-09.

- ↑ Tavernise, Sabrina. "In Turkey, a Sign of a Rising Islamic Middle Class," New York Times, April 25, 2007.

- ↑ "Turkey 'must have secular leader'", BBC News, April 24, 2007.

- ↑ Tavernise, Sabrina. "Ruling Party in Turkey Wins Broad Victory," New York Times, July 23, 2007.

- ↑ "Secular rally targets Turkish PM". BBC News. 2007-04-14. Retrieved 2008-08-05.

- 1 2 "The Islamic veil across Europe". BBC News. 2006-11-17. Retrieved 2006-12-13.

- 1 2 "Leyla Şahin v. Turkey". European Court of Human Rights. 2005-11-10. Retrieved 2008-08-21.

- ↑ Çarkoğlu, Ali (2004). Religion and Politics in Turkey. UK: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-34831-5.

- ↑ State ID cards, General Directorate of Population and Citizenship Matters, Ministry of the Interior (in Turkish)

- ↑ Fox, Jonathan. World Survey of Religion and the State, Cambridge University Press, 2008, ISBN 978-0-521-70758-9, page 247

- ↑ "T.C. Diyanet İşleri Başkanlığı, Namaz Vakitleri, Duyurular, Haberler". Diyanet.gov.tr. Retrieved 2013-09-28.

- ↑ Samim Akgönül - Religions de Turquie, religions des Turcs: nouveaux acteurs dans l'Europe élargie - L'Harmattan - 2005 - 196 pages

- 1 2 3 The World of the Alevis: Issues of Culture and Identity, Gloria L. Clarke

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "Le gouvernement turc va restituer des biens saisis à des minorités religieuses" (in French). La-Croix.com. 2011-08-29. Retrieved 2013-09-28.

- ↑ http://www.tbmm.gov.tr/anayasa/anayasa_2011.pdf

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 http://obtic.org/Dosyalar/Cahiers%20de%20l%27Obtic/CahiersObtic_2.pdf

- ↑ "Les Janissaires (1979) de Vincent Mansour Monteil : JANISSAIRE" (in French). Janissaire.hautetfort.com. 2008-05-14. Retrieved 2013-09-28.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Jean-Paul Burdy. "Les minorités non musulmanes en Turquie : "certains rapports d’ONG parlent d’une logique d’attrition"" (in French). Observatoire de la Vie Politique Turque(Ovipot.hypotheses.org). Retrieved 2013-09-28.

- 1 2 "Persée". Persee.fr. Retrieved 2013-09-28.

- ↑ Rapport Minority Rights Group Bir eşitlik arayışı: Türkiye’de azınlıklar Uluslararası Azınlık Hakları Grubu 2007 Dilek Kurban

- ↑ Pirsultan psakd Antalya (2006-08-16). "Dünyada ve Türkiye'de NUSAYRİLİK" (in Turkish). psakd.org. Retrieved 2013-09-28.

- ↑ Andrea Riccardi, Il secolo del martirio, Mondadori, 2009, pag. 281.

- ↑ "Foreign Ministry: 89,000 minorities live in Turkey". Today's Zaman. 2008-12-15. Retrieved 2008-12-15.

- ↑ The Greeks of Turkey, 1992-1995 Fact-sheet by Marios D. Dikaiakos

- ↑ Christen in der islamischen Welt – Aus Politik und Zeitgeschichte (APuZ 26/2008)

- ↑ Turay, Anna. "Tarihte Ermeniler". Bolsohays: Istanbul Armenians. Archived from the original on 6 December 2006. Retrieved 2007-01-04. External link in

|publisher=(help) - ↑ Hür, Ayşe (2008-08-31). "Türk Ermenisiz, Ermeni Türksüz olmaz!". Taraf (in Turkish). Archived from the original on 2 September 2008. Retrieved 2008-09-02.

Sonunda nüfuslarını 70 bine indirmeyi başardık.

- ↑ La politique turque en question: entre imperfections et adaptations (in French). Books.google.fr. Retrieved 2013-09-28.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 http://www.tbmm.gov.tr/butce/2013/kanun_tasarisi.pdf

- ↑ United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. "Turkey: Situation of women who wear headscarves". UNHCR Unhcr.org. Retrieved 2013-09-28.

- ↑ Lamb, Christina (2007-04-23). "Head scarves to topple secular Turkey?". The Times. London.

- ↑ Lamb, Christina (2007-05-06). "Headscarf war threatens to split Turkey". Times Online. London.

- ↑ Clark-Flory, Tracy (2007-04-23). "Head scarves to topple secular Turkey?". Salon.com. Retrieved 2008-08-04.

- ↑ Turkey, Britannica Online Encyclopedia

Further reading

- Ahmet T. Kuru. Secularism and State Policies toward Religion The United States, France, and Turkey Cambridge University Press, 2009.

- Sevinc, K., Hood, R. W. Jr., Coleman, T. J. III, (2017). Secularism in Turkey. In Zuckerman, P., & Shook, J. R., (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Secularism. Oxford University Press.