Northwest Territory

| Territory Northwest of the River Ohio | |||||

| Organized incorporated territory of United States | |||||

| |||||

|

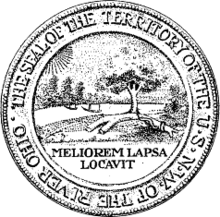

Seal | |||||

| Motto Meliorem lapsa locavit "He has planted one better than the one fallen" | |||||

| |||||

| Capital | Marietta (1788–1799) Chillicothe (1799–1803)[1] | ||||

| Government | Organized incorporated territory | ||||

| Governor | |||||

| • | 1787–1802 | Arthur St. Clair | |||

| • | 1802–1803 | Charles Willing Byrd | |||

| History | |||||

| • | Northwest Ordinance | July 13, 1787 | |||

| • | Affirmed by United States Congress | August 7, 1789 | |||

| • | Indiana Territory created | May 7, 1800 | |||

| • | Statehood of Ohio | March 1, 1803 | |||

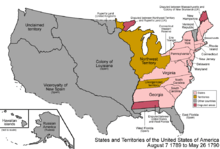

The post-American Revolutionary War Territory Northwest of the River Ohio, more commonly known as the Northwest Territory encompassing most of the pre-war territory of the Ohio Country, parts of Illinois Country, and parts of old French Canada below the Great Lakes was an organized incorporated territory of the United States spanning most or large parts of six eventual U.S. States. It existed legally from July 13, 1787, until March 1, 1803, when the southeastern portion of the territory was admitted to the Union as the state of Ohio, and the remainder was reorganized by additional legislative actions.

In the 18th century, Great Britain and the France disputed for control of this region. The French had claimed it in the 17th century as part of New France; the competition between these empires was one cause of the French and Indian War (known as the Seven Years' War in Europe). After Britain gained control following its defeat of France in 1763, its attempts to reserve territory for use by Native Americans, under the Royal Proclamation of 1763, and for a new colony the British Province of Quebec, roused resentment among British colonists, who were already seeking to settle west of the Appalachian Mountains.

The region was assigned to the United States in the Treaty of Paris of 1783, but sporadic westward emigrant settlements had already resumed late in the war after the Iroquois Confederation's power was broken and the tribes scattered by the 1779 Sullivan Expedition. It boomed soon after the Revolution ended as the westward traffic spurred expansion of a gateway trading post into the town of Brownsville, Pennsylvania as a key outfitting center west of the mountains. Other wagon roads, such as the Kittanning Path surmounting the gaps of the Allegheny in central Pennsylvania, or trails along the Mohawk River in New York let a steady stream of settlers reach the near west and the lands bordering the Mississippi.[lower-alpha 1] This activity stimulated the development of the eastern parts of the eventual National Road by private investors. The Cumberland–Brownsville toll road linked the water routes of the Potomac River with the Monongahela River of the Ohio/Mississippi riverine systems in the days when water travel was the only good alternative to walking and riding. Most of the territory and its successors was settled by emigrants passing through the Cumberland Narrows, or along the Mohawk Valley in New York State.

The Congress of the Confederation enacted the Northwest Ordinance in 1787 to provide for the administration of the territories and set rules for admission of jurisdictions as states. On August 7, 1789, the new U.S. Congress affirmed the Ordinance with slight modifications under the Constitution. The territory included all the land of the United States west of Pennsylvania and northwest of the Ohio River. It covered all of the modern states of Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Michigan, and Wisconsin, as well as the northeastern part of Minnesota. The area covered more than 260,000 square miles (670,000 km2).

History

European exploration of the region began with French-Canadian voyageurs in the 17th century, followed by French missionaries and French fur traders. French-Canadian explorer Jean Nicolet was the first recorded European entrant into the region, landing in 1634 at the current site of Green Bay, Wisconsin (although Étienne Brûlé is stated by some sources as having explored Lake Superior and possibly inland Wisconsin in 1622). The French exercised control from widely separate posts in the region, which they claimed as New France; among these was the post at Fort Detroit, founded in 1701. France ceded the territory to the Kingdom of Great Britain as part of the Indian Reserve in the 1763 Treaty of Paris, after being defeated in the French and Indian War (and Seven Years' War in Europe).

British control

From the 1750s to the peace treaty that ended the War of 1812, the British had a long-standing goal of creating an Indian barrier state, a large "neutral" Indian state that would cover most of the Old Northwest. It would be independent of the United States and under the tutelage of the British, who would use it to block American expansion and to build up their control of the fur trade headquartered in Montreal.[2]

A new colony, named Charlotina, was proposed for the southern Great Lakes region. However, facing armed opposition by Native Americans, the British issued the Proclamation of 1763, which prohibited white colonial settlement west of the Appalachian Mountains. This action angered American colonists interested in expansion, as well as those who had already settled in the area. In 1774, by the Quebec Act, Britain annexed the region to the Province of Quebec in order to provide a civil government and to centralize British administration of the Montreal-based fur trade. The prohibition of settlement west of the Appalachians remained, contributing to the American Revolution.

American Revolution

In February 1779, George Rogers Clark of the Virginia Militia captured Kaskaskia and Vincennes from British commander Henry Hamilton. Virginia capitalized on Clark's success by laying claim to the whole of the Old Northwest, calling it Illinois County, Virginia,[3] until 1784, when Virginia ceded its land claims to the federal government.

The Old Northwest Territory included all the then-owned land of the United States west of Pennsylvania, east of the Mississippi River, and northwest of the Ohio River. It covered all of the modern states of Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Michigan, and Wisconsin, as well as the northeastern part of Minnesota. The area covered more than 260,000 square miles (670,000 km2) and was a significant addition to the United States. It was inhabited by about 45,000 Native Americans and 4,000 traders, mostly Canadien and British – although both groups included the Metis, a sizeable group descended from Native women married to European or Canadian traders who established a unique culture that ruled the Upper Midwest for more than a century.

Britain officially ceded the area north of the Ohio River and west of the Appalachians to the United States at the end of the American Revolutionary War with the Treaty of Paris (1783), but the British continued to maintain a presence in the region as late as 1815, the end of the War of 1812.

Several states (Virginia, Massachusetts, New York, and Connecticut) then had competing claims on the territory. Other states, such as Maryland, refused to ratify the Articles of Confederation so long as these states were allowed to keep their western territory, fearing that those states could continue to grow and tip the balance of power in their favor under the proposed system of federal government. As a concession in order to obtain ratification, these states ceded their claims on the territory to the federal government: New York in 1780, Virginia in 1784, Massachusetts and Connecticut in 1785. So the majority of the territory became public land owned by the U.S. government. Virginia and Connecticut reserved the land of two areas to use as compensation to military veterans: The Virginia Military District and the Connecticut Western Reserve. In this way, the United States included territory and people outside any of the states.

Thomas Jefferson's Land Ordinance of 1784 was the first organization of the territory by the United States. The Land Ordinance of 1785 established a standardized system for surveying the land into saleable lots, although Ohio would be partially surveyed several times using different methods, resulting in a patchwork of land surveys in Ohio. Some older French communities' property claims based on earlier systems of long, narrow lots also were retained. The rest of the Northwest Territory was divided into roughly uniform square townships and sections, which facilitated land sales and development. The ordinance also stipulated that the territory would eventually form at least three- but not more than five- new states.[4] American settlement officially began at Marietta, Ohio, on April 7, 1788, with the arrival of forty-eight pioneers.

Indian wars

The young United States government, deeply in debt following the Revolutionary War and lacking authority to tax under the Articles of Confederation, planned to raise revenue from the methodical sale of land in the Northwest Territory. This plan necessarily called for the removal of both Native American villages and squatters from the Eastern U.S.[5] Difficulties with Native American tribes and a supporting British military presence presented continuing obstacles for American expansion. As late as 1791, Rufus Putnam wrote to President Washington that "we shall be so reduced and discouraged as to give up the settlement."[6] The military campaign of General "Mad" Anthony Wayne against the Native Americans, who were supported by a British company, eventually culminated with victory at the Battle of Fallen Timbers in 1794 and the Treaty of Greenville of 1795. Jay's Treaty, in 1794, temporarily helped to smooth relations with British traders in the region, where British citizens outnumbered American citizens throughout the 1790s.

Furthermore, in regards to the Leni Lenape Native Americans living in the region, Congress decided that 10,000 acres on the Muskingum River in the present state of Ohio would "be set apart and the property thereof be vested in the Moravian Brethren . . . or a society of the said Brethren for civilizing the Indians and promoting Christianity."[7]

The first governor of the Northwest Territory, Arthur St. Clair, formally established the government on July 15, 1788, at Marietta. His original plan called for the organization of five initial counties: Washington (Ohio east of the Scioto River), Hamilton (Ohio between the Scioto and the Miami Rivers), Knox (Indiana and eastern Illinois), St. Clair (Illinois and Wisconsin), and Wayne (Michigan).

Under the Northwest Ordinance of 1787, which created the Northwest Territory, General St. Clair was appointed governor of what is now Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Michigan, along with parts of Wisconsin and Minnesota. He named Cincinnati, Ohio, after the Society of the Cincinnati, and it was there that he established his home. When the territory was divided in 1800, he served as governor of the Ohio Territory.

As Governor, he formulated the Maxwell Code (named after its printer, William Maxwell), the first written laws of the territory. He also sought to end Native American claims to Ohio land and clear the way for white settlement. In 1789, he succeeded in getting certain Indians to sign the Treaty of Fort Harmar, but many native leaders had not been invited to participate in the negotiations, or had refused to do so. Rather than settling the Indian's claims, the treaty provoked them to further resistance in what is sometimes known as the "Northwest Indian War" (or "Little Turtle's War"). Mutual hostilities led to a campaign by General Josiah Harmar, whose 1,500 militiamen were defeated by the Indians in October 1790.[8]

In March 1791, St. Clair succeeded Harmar as commander of the United States Army and was commissioned as a major general. He personally led a punitive expedition involving two Regular Army regiments and some militia. In October 1791 as an advance post for his campaign, Fort Jefferson (Ohio) was built under the direction of General Arthur St. Clair. Located in present-day Darke County in far western Ohio, the fort was built of wood and intended primarily as a supply depot; accordingly, it was originally named Fort Deposit. One month later, near modern-day Fort Recovery, his force advanced to the location of Indian settlements near the headwaters of the Wabash River, but on November 4 they were routed in battle by a tribal confederation led by Miami Chief Little Turtle and Shawnee chief Blue Jacket. More than 600 soldiers and scores of women and children were killed in the battle, which has since borne the name "St. Clair's Defeat", also known as the "Battle of the Wabash", the "Columbia Massacre," or the "Battle of a Thousand Slain". It remains the greatest defeat of a US Army by Native Americans in history, with about 623 American soldiers killed in action and about 50 Native American killed. Although an investigation exonerated him, St. Clair resigned his army commission in March 1792 at the request of President Washington, but continued to serve as Governor of the Northwest Territory.[9][10][11]

.jpg)

A Federalist, St. Clair hoped to see two states made of the Ohio Territory in order to increase Federalist power in Congress. However, he was resented by Ohio Democratic-Republicans for what were perceived as his partisanship, high-handededness and arrogance in office. In 1802, his opposition to plans for Ohio statehood led President Thomas Jefferson to remove him from office as territorial governor. He thus played no part in the organizing of the state of Ohio in 1803. The first Ohio Constitution provided for a weak governor and a strong legislature, in part due to a reaction to St. Clair's method of governance.

Statehood for Ohio

On July 4, 1800, in preparation for Ohio's statehood, the Indiana Territory was decreed by an act of the U.S. Congress, signed into law by President John Adams on May 7, 1800, effective on July 4. The Congressional legislation encompassed all land west of the present Indiana–Ohio border and its northward extension to Lake Superior, reducing the Northwest Territory to present-day Ohio and the eastern half of Michigan's Lower Peninsula. Ohio was admitted as a state on March 1, 1803, at the same time the remaining land was annexed to Indiana Territory, and the Northwest Territory went out of existence. Ongoing disputes with the British over the region was a contributing factor to the War of 1812. Britain irrevocably ceded claim to the former Northwest Territory with the Treaty of Ghent in 1814.

Education

The 1784 Northwest Ordinance called for a public university for the education, settlement and eventual statehood of the frontier of Ohio and beyond. Article 3 stated "Religion, morality and knowledge being necessary to good government and the happiness of mankind, schools and the means of education shall forever be encouraged." In 1786, Manasseh Cutler became interested in the settlement of western lands by American pioneers to the Northwest Territory. The following year, as agent of the Ohio Company of Associates that he had been involved in creating, he organized a contract with Congress whereby his associates (former soldiers of the Revolutionary War) might purchase one and a half million acres (6,000 km²) of land at the mouth of the Muskingum River with their Certificate of Indebtedness. Cutler greatly impacted the Ordinance of 1787 for the government of the Northwest Territory, which was finally presented to Congress by Massachusetts delegate Nathan Dane. In order to smooth passage of the Northwest Ordinance, Cutler bribed key congressmen by making them partners in his land company. In changing the office of provisional governor from an elected to an appointed position, Cutler was able to offer the position to the president of Congress, Arthur St. Clair.[12]

The Land Ordinance of 1785 created an innovation in public education when it reserved resources for local public schools. The ordinance divided the territory into 36 mile2 townships, and each township was further divided into 36 one mile2 tracts for purposes of sale. The ordinance then stated that "there shall be reserved from sale the lot No. 16 of every township for the maintenance of public schools within the said township."[13]

In 1801, Jefferson Academy was established in Vincennes. As Vincennes University, it remains the oldest public institution of higher learning from the Northwest Territory.

The next year, American Western University was created in Athens, Ohio, upstream of the Hocking River, due to its location directly between Chillicothe (an original capital of Ohio) and Marietta. It was formally established on February 18, 1804 as Ohio University, when its charter instrument was approved by the Ohio General Assembly.[14] Its establishment came 11 months after Ohio was admitted to the Union. The first three students enrolled in 1808. Ohio University graduated two students with bachelor's degrees in 1815.

Law and government

At first, the territory had a modified form of martial law. The governor was also the senior army officer within the territory, and he combined legislative and executive authority. But a supreme court was established, and he shared legislative powers with the court. County governments were organized as soon as the population was sufficient, and these assumed local administrative and judicial functions. Washington County was the first of these, at Marietta in 1788. This was an important event, as this court was the first establishment of civil and criminal law in the pioneer country.

As soon as the number of free male settlers exceeded 5,000, the Territorial Legislature was to be created, and this happened in 1798. The full mechanisms of government were put in place, as outlined in the Northwest Ordinance. A bicameral legislature consisted of a House of Representatives and a Council. The first House had 22 representatives, apportioned by population of each county.[15] The House then nominated 10 citizens to be Council members. The nominations were sent to the U.S. Congress, which appointed five of them as the Council. This assembly became the legislature of the Territory, although the governor retained veto power.

Article VI of the Articles of Compact within the Northwest Ordinance prohibited the owning of slaves within the Northwest Territory. However, territorial governments evaded this law by use of indenture laws.[16] The Articles of Compact prohibited legal discrimination on the basis of religion within the territory.

The township formula created by Thomas Jefferson was first implemented in the Northwest Territory through the Land Ordinance of 1785. The square surveys of the Northwest Territory would become a hallmark of the Midwest, as sections, townships, counties (and states) were laid out scientifically, and land was sold quickly and efficiently (although not without some speculative aberrations).

Officials

Arthur St. Clair was the territory's governor until November 1802, when President Thomas Jefferson removed him from office and appointed Charles Willing Byrd, who served the position until Ohio became a state and elected its first governor, Edward Tiffin, on March 3, 1803.[17] The Supreme Court consisted of (1) John Cleves Symmes, (2) James Mitchell Varnum, died 1789, replaced by George Turner, who resigned in 1796, and was replaced by Return Jonathan Meigs, Jr., and (3) Samuel Holden Parsons, died 1789, replaced by Rufus Putnam, who resigned 1796, and was replaced by Joseph Gilman.[18] There were three secretaries: Winthrop Sargent (July 9, 1788 – May 31, 1798); William Henry Harrison (June 29, 1798 – December 31, 1799); and Charles Willing Byrd (January 1, 1800 – March 1, 1803).

The territory's first common pleas court opened at Marietta on September 2, 1788. Its first judges were General Rufus Putnam, General Benjamin Tupper, and Colonel Archibald Crary. Ebenezer Sproat was the first sheriff, Paul Fearing became the first attorney to practice in the territory, and Colonel William Stacy was foreman of the first grand jury.[19] Griffin Greene was appointed justice of the peace.

Winthrop Sargent, the first secretary of the territory, married Roewena Tupper, daughter of Gen. Benjamin Tupper, on February 6, 1789 at Marietta in the first marriage ceremony held within the Northwest Territory.[20]

General Assembly

The General Assembly of the Northwest Territory consisted of a Legislative Council (five members chosen by Congress) and a House of Representatives consisting of 22 members elected by the male freeholders in nine counties. The first session of the Assembly was held in September 1799. Its first important task was to select a non-voting delegate to the U.S. Congress. Locked in a power struggle with Governor St. Clair, the legislature narrowly elected William Henry Harrison as the first delegate over the governor's son, Arthur St. Clair, Jr. Subsequent congressional delegates were William McMillan (1800–1801) and Paul Fearing (1801–1803).

The first session of the First Territorial Legislature met from September 16 to December 19, 1799 at Cincinnati.[21]

| first session, First Territorial Legislature 1799 Legislative Council | ||

|---|---|---|

| County | Councilman | Notes |

| Hamilton | Jacob Burnet | |

| James Findlay | ||

| Washington | Robert Oliver | |

| Jefferson | David Vance | |

| Knox | Henry Vanderburgh | President of the Council |

| first session, First Territorial Legislature 1799 House of Representatives | ||

|---|---|---|

| County | Representative | Notes |

| Adams | Joseph Darlinton | |

| Hamilton | Robert Benham | |

| Aaron Caldwell | ||

| William Goforth | ||

| John Ludlow | ||

| Isaac Martin | ||

| William McMillan | ||

| John Smith | ||

| Jefferson | James Pritchard | |

| Knox | John Small | |

| Randolph | John Edgar | |

| Ross | Samuel Findlay | |

| Elias Langham | ||

| Nathaniel Massie | ||

| Edward Tiffin | Speaker of the House | |

| Thomas Worthington | ||

| St. Clair | Shadrach Bond, Sr. | |

| Washington | Paul Fearing | |

| Return Jonathan Meigs, Jr. | ||

| Wayne | Charles Francois Chobert de Joncaire | |

| Solomon Sibley | ||

| Jacob Visgar | ||

The second session of the First Territorial Legislature met from November 3 to December 9, 1800 at Chillicothe.[22]

| second session, First Territorial Legislature 1800 Legislative Council | ||

|---|---|---|

| County | Councilman | Notes |

| Hamilton | Jacob Burnet | |

| James Findlay | ||

| Washington | Robert Oliver | President of the Council |

| Jefferson | David Vance | |

| second session, First Territorial Legislature 1800 House of Representatives | ||

|---|---|---|

| County | Representative | Notes |

| Adams | Joseph Darlinton | |

| Nathaniel Massie | seated November 10 | |

| Hamilton | Robert Benham | |

| William Goforth | ||

| John Ludlow | vice Aaron Caldwell, removed from territory | |

| William Lytle | ||

| Isaac Martin | ||

| William McMillan | resigned when he was elected to Congress | |

| John Smith | ||

| Jefferson | Zenas Kimberly | |

| James Pritchard | ||

| Ross | Samuel Findlay | |

| Elias Langham | ||

| Edward Tiffin | Speaker of the House | |

| Thomas Worthington | ||

| Washington | Paul Fearing | |

| Return Jonathan Meigs, Jr. | ||

| Wayne | Charles Francois Chobert de Joncaire | |

| Solomon Sibley | ||

| Jacob Visgar | ||

The first session of the Second Territorial Legislature met from November 23, 1801 to January 23, 1802 at Chillicothe.[23]

| first session, Second Territorial Legislature 1801–1802 Legislative Council | ||

|---|---|---|

| County | Councilman | Notes |

| Hamilton | Jacob Burnet | |

| Washington | Robert Oliver | President of the Council |

| Jefferson | David Vance | |

| Wayne | Solomon Sibley | |

| first session, Second Territorial Legislature 1801–1802 House of Representatives | ||

|---|---|---|

| County | Representative | Notes |

| Adams | Joseph Darlinton | |

| Nathaniel Massie | ||

| Hamilton | Francis Dunlavy | |

| John Ludlow | ||

| Moses Miller | ||

| Jeremiah Morrow | ||

| Daniel Reeder | ||

| John Smith | ||

| Jacob White | ||

| Jefferson | Zenas Kimberly | |

| Thomas McCune | ||

| John Milligan | ||

| Ross | Elias Langham | seated November 26 |

| Edward Tiffin | Speaker of the House | |

| Thomas Worthington | ||

| Trumbull | Edward Paine | |

| Washington | Ephraim Cutler | |

| Rufus Putnam | ||

| Wayne | Charles Francois Chobert de Joncaire | |

| George McDougal | ||

| Jonathan Schiefflein | ||

The second session of the Second Territorial Legislature was scheduled to begin the fourth Monday in November, 1802 at Cincinnati. As the Ohio Constitutional Convention was then in session, no attempt was made to convene the body by members or the territorial governor.[24]

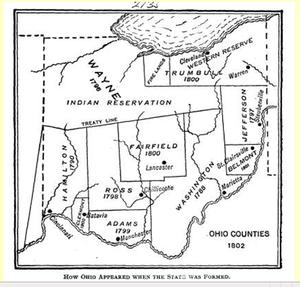

Territorial counties

13 counties were formed by Governor Arthur St. Clair during the territory's existence:

- Washington County, with its seat at Marietta, was the first county formed in the territory, proclaimed on July 26, 1788 by territorial governor St. Clair. Its original boundaries were proclaimed as all of present-day Ohio east of a line extending due south from the mouth of the Cuyahoga River,[26] but this did not take into account Connecticut's still unresolved claim of the Western Reserve. It kept these boundaries until 1796.

- Hamilton County, with its seat at Cincinnati, was proclaimed on January 2, 1790. The same proclamation officially changed Cincinnati's name from Losantiville into its present form. Its original boundaries claimed all land north of the Ohio between the Great Miami River and Little Miami River as far north as Standing Stone Fork (now Loramie Creek), just north of present-day Piqua.[27] In 1792 Hamilton County was expanded to encompass all lands between the mouths of the Great Miami and Cuyahoga Rivers, as well as all of what is now the Lower Peninsula of Michigan. Its territory was reduced several times after 1796.

- St. Clair County, with its seat at Kaskaskia was proclaimed on April 27, 1790. It originally encompassed most of present-day Illinois south of the Illinois River. It lost most of its southern lands in the formation of Randolph County in 1795, necessitating the transfer of the county seat to Cahokia, but would expand to the north to take in northwest present-day Illinois and most of present-day Wisconsin in 1801 after becoming part of Indiana Territory.[28]

- Knox County, with its seat at Vincennes, was proclaimed on June 20, 1790, and encompassed the majority of the territory's land area – all land between St. Clair County and Hamilton County, extending north to Canada.[29]

- Randolph County was formed October 5, 1795 with its seat at Kaskaskia and encompassed the southern half of what was St. Clair County.

- Wayne County was formed on August 15, 1796, out of portions of Hamilton County and unorganized land, with its seat at Detroit, which had been evacuated by the British five weeks previously. Wayne County originally covered all of Michigan's Lower Peninsula, northwestern Ohio, northern Indiana and a small portion of the present Lake Michigan shoreline, including the site of present-day Chicago. The lands west of the extension of the present Indiana-Ohio border became part of Indiana Territory in 1800; the eastern portion of the county's land in Ohio were folded into Trumbull County that same year. The territory north of the Ordinance Line became part of Indiana Territory in 1803 as a reorganized Wayne County; the remainder reverted to unorganized status after Ohio statehood.

- Adams County was formed on July 10, 1797, with its seat at Manchester; it encompassed most of present-day south central Ohio.

- Jefferson County was formed July 29, 1797 with its seat at Steubenville, carved out of Washington County and originally encompassed all of what is now northeastern Ohio.

- Ross County was organized on August 20, 1798 with its seat at Chillicothe and was carved out of portions of Knox, Hamilton and Washington counties.

Knox, Randolph and St. Clair counties were separated from the territory effective July 4, 1800, and, along with the western part of Wayne County, and unorganized lands in what are now Minnesota and Wisconsin, became the Indiana Territory.

- Trumbull County was proclaimed July 10, 1800 out of the Western Reserve portion of Jefferson and Wayne Counties, with its county seat at Warren, chosen over rivals Cleveland and Youngstown.[30]

- Clermont County was formed December 6, 1800 out of Hamilton County, with its seat at Williamsburg. In contrast with most other Northwest Territory counties, Clermont County's original boundaries are only slightly larger than its present-day limits.

- Fairfield County was proclaimed December 9, 1800, formed out of Ross and Washington counties, with its seat at Lancaster.

- Belmont County was proclaimed September 7, 1801, formed out of Washington and Jefferson counties, with its seat at St. Clairsville.

The Northwest Territory ceased to exist upon Ohio statehood on March 1, 1803; the lands in Ohio that were previously part of Wayne County but not included in Trumbull County reverted to an unorganized status until new counties could be formed. The remainder of Wayne County, roughly the eastern half of the Lower Peninsula of Michigan and the eastern tip of the Upper Peninsula, was attached to Indiana Territory.

Territorial contributions

- US states that ceded territorial claims in what would become the Northwest Territory:

- State of New York, 1780–1782

- Commonwealth of Virginia, 1781–1784

- Commonwealth of Massachusetts, 1784–1785

- State of Connecticut, 1786 and 1800

- U.S. territories that encompassed land that was previously part of the Northwest Territory:

- Territory of Indiana, 1800–1816

- Territory of Michigan, 1805–1837

- Territory of Illinois, 1809–1818

- Territory of Wisconsin, 1836–1848

- Territory of Minnesota, 1849–1858

- US states that encompass land that was once part of the Northwest Territory:

- State of Ohio, 1803

- State of Indiana, 1816

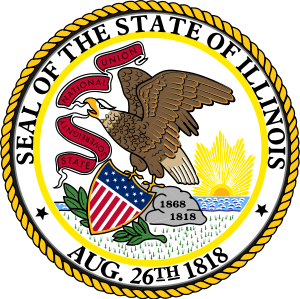

- State of Illinois, 1818

- State of Michigan, 1837

- State of Wisconsin, 1848

- State of Minnesota, 1858

See also

- American pioneers to the Northwest Territory

- Historic regions of the United States

- History of Ohio

- Illinois-Wabash Company

- Indian barrier state

- Northwest Indian War

- Northwestern University – Created in 1851 to serve the people of the former Northwest Territory

- Ohio Country

- Ohio University – First institution of higher education chartered by an Act of Congress in America (Northwest Ordinance)

- Zane's trace

Notes

- ↑ Before the 1803 Louisiana Purchase, the western border of U.S. territory ended on the Mississippi; the lands beyond still being a possession of Napoleonic France or the Kingdom of Spain.

References

- ↑ "Northwest Territory". HowStuffWorks. Retrieved August 10, 2013.

- ↑ Dwight L. Smith, "A North American Neutral Indian Zone: Persistence of a British Idea," Northwest Ohio Quarterly 61#2-4 (1989): 46-63.

- ↑ Palmer, pp. 400–421.

- ↑ Calloway, Colin G. (2015). The Victory with No Name. The Native American Defeat of the First American Army. Oxford University Press. p. 50.

- ↑ Calloway, Colin G. (2015). The Victory with No Name. The Native American Defeat of the First American Army. Oxford University Press. p. 38.

- ↑ Winkler, John F. (2011). Wabash 1791: St. Clair's Defeat; Osprey Campaign Series #240. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. p. 15. ISBN 1-84908-676-1.

- ↑ "Religion and the Congress of the Confederation, 1774–89". Library of Congress. Retrieved November 4, 2012.

- ↑ Michael S. Warner, "General Josiah Harmar's Campaign Reconsidered: How the Americans Lost the Battle of Kekionga." Indiana Magazine of History (1987): 43–64. online

- ↑ Leroy V. Eid, "American Indian Military Leadership: St. Clair’s 1791 Defeat." Journal of Military History 57.1 (1993): 71–88.

- ↑ William O. Odo, "Destined for Defeat: an Analysis of the St. Clair Expedition of 1791." Northwest Ohio Quarterly (1993) 65#2 pp: 68–93.

- ↑ John F. Winkler, Wabash 1791: St Clair's Defeat (Osprey Publishing, 2011)

- ↑ McDougall, Walter A. Freedom Just Around the Corner: A New American History, 1585–1828. (New York: Harper Collins, 2004), p. 289.

- ↑ Knight, George Wells (1885). History and Management of Land Grants for Education in the Northwest Territory (Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Michigan, Wisconsin). G. P. Putnam's Sons. p. 13.

- ↑ "Ohio University". Ohio History Central: An Online Encyclopedia of Ohio History. Retrieved December 31, 2009.

- ↑ Ohio General Assembly (1917). Manual of Legislative Practice in the General Assembly. State of Ohio. p. 199.

- ↑ "Slavery in Indiana Territory". Indiana Historical Bureau. Archived from the original on July 21, 2007. Retrieved July 24, 2013.

- ↑ Burtner, W. H., Jr. (1998). "Charles Willing Byrd". 41. Ohio Historical Society: 237.

- ↑ Force, Manning, ed. (1897). "The Supreme Court – a Historical Sketch". Bench and Bar of Ohio: a Compendium of History and Biography. 1. Chicago: Century Publishing and Engraving Company. p. 5.

- ↑ Hildreth, S. P. (1848). Pioneer History: Being an Account of the First Examinations of the Ohio Valley, and the Early Settlement of the Northwest Territory. Cincinnati, Ohio: H. W. Derby and Co. pp. 232–33.

- ↑ Zimmer, L. (1987). True Stories from Pioneer Valley. Marietta, Ohio: Broughton Foods. p. 20.

- ↑ Gilkey, pp. 131–133.

- ↑ Gilkey, pp. 136–139.

- ↑ Gilkey, pp. 142–143.

- ↑ Gilkey, p. 143.

- ↑ Reinke, Edgar C. "Meliorem Lapsa Locavit: An Intriguing Puzzle Solved". Ohio History. 94: 74. says the young tree on the seal of the NWT is an apple, while Summers, Thomas J. (1903). History of Marietta. Marietta, Ohio: Leader Publishing. p. 115. says it is a buckeye, and perhaps the genesis of Ohio's nickname.

- ↑ Griswold, S.O. (1884). The Corporate Birth and Growth of the City of Cleveland. Western Reserve and Northern Ohio Historical Society. Tract No. 62.

- ↑ Unknown (1894). History of Cincinnati and Hamilton County. S.B. Nelson & Co.

- ↑ Walton, W.C. (1928). A Brief History of St. Clair County. McKendree College.

- ↑ Esarey, Logan (1915). A History of Indiana. W.K. Stewart Co. p. 137.

- ↑ "Historical Information for the Target Investment Areas Trumbull County and the Historic Western Reserve". Trumbull County. Archived from the original on March 20, 2005.

Further reading

- Barnhart, Terry A. "'A Common Feeling': Regional Identity and Historical Consciousness in the Old Northwest, 1820-1860." Michigan Historical Review (2003): 39-70. in JSTOR

- Barr, Daniel P. The Boundaries Between Us: Natives and Newcomers Along the Frontiers of the Old Northwest Territory, 1750-1850 (Kent State University Press, 2006)

- Beatty-Medina, Charles, and Melissa Rinehart, eds. Contested Territories: Native Americans and Non-natives in the Lower Great Lakes, 1700-1850 (Michigan State University Press, 2012)

- Buley, R. Carlyle. The Old Northwest: Pioneer Period, 1815-1840 (2 vols., Bloomington, Ind., 1951). Pulitzer Prize for history

- Buley, R. Carlyle. "Pioneer health and medical practices in the old northwest prior to 1840." Mississippi Valley Historical Review (1934): 497-520. in JSTOR

- Calloway, Colin G. The Victory with No Name: The Native American Defeat of the First American Army (Oxford University Press, 2014)

- Davis, James E. "" New Aspects of Men and New Forms of Society": The Old Northwest, 1790-1820." Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society (1976): 164-172. in JSTOR

- Elkins, Stanley, and Eric McKitrick. "A Meaning for Turner's Frontier: Part I: Democracy in the Old Northwest." Political Science Quarterly (1954): 321-353. in JSTOR

- Esarey, Logan. "Elements of Culture in the Old Northwest." Indiana Magazine of History (1957): 257-264. online

- Heath, William. William Wells and the Struggle for the Old Northwest (University of Oklahoma Press, 2015) he lived 1770-1812

- Kuhns, Frederck I., "Home Missions and Education in the Old Northwest." Journal of the Presbyterian Historical Society (1953): 137-155. in JSTOR

- Owens, Robert M. Mr. Jefferson's hammer: William Henry Harrison and the origins of American Indian policy (University of Oklahoma Press, 2012)

- Ubbelohde, Carl. "History and the Midwest as a Region." Wisconsin Magazine of History (1994): 35-47. in JSTOR

- Zimmer, Louise (1987). True Stories of Pioneer Times. Marietta, Ohio: Broughton Foods.

- ——— (1993). More True Stories from Pioneer Valley. Marietta, Ohio: Sugden Book Store.

Older sources

- Barker, Joseph (1958). Recollections of the First Settlement of Ohio. Marietta, Ohio: Marietta College. Original manuscript written late in Joseph Barker's life, prior to his death in 1843

- Gilkey, Elliot Howard, ed. (1901). The Ohio Hundred Year Book: a Hand-book of the Public Men and Public Institutions of Ohio ... State of Ohio.

- Hildreth, S. P. (1848). Pioneer History: Being an Account of the First Examinations of the Ohio Valley, and the Early Settlement of the Northwest Territory. Cincinnati, Ohio: H. W. Derby and Co.

- Hildreth, S. P. (1852). Biographical and Historical Memoirs of the Early Pioneer Settlers of Ohio. Cincinnati, Ohio: H. W. Derby and Co.

- Hulbert, Archer Butler (1917). The Records of the Original Proceedings of the Ohio Company, Volumes I and 2. Marietta, Ohio: Marietta Historical Commission.

- Lindley, H.; Schneider, N. & Quaife, M. (1937). History of the Ordinance of 1787 and the Old Northwest Territory (A Supplemental Text for School Use). Marietta, Ohio: Northwest Territory Celebration Commission.

- Morse, J. (1797). "North-West Territory". The American Gazetteer. Boston, Massachusetts: S. Hall, and Thomas & Andrews.

- Summers, Thomas J. (1903). History of Marietta. Marietta, Ohio: Leader Publishing.

External links

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Northwest Territory. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1905 New International Encyclopedia article Northwest Territory. |

- Facsimile of 1789 Act

- The Territory's Executive Journal

- Maumee Valley Heritage Corridor

- Prairie Fire: The Illinois Country 1673–1818, Illinois Historical Digitization Projects at Northern Illinois University Libraries

Coordinates: 41°N 86°W / 41°N 86°W