Second Madagascar expedition

| Second Madagascar expedition (1894-95) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Franco-Hova Wars | |||||||

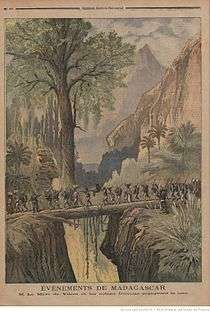

French infantry landing at Majunga, May 1895. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

15,000 men 6,000 porters | ? | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 25 killed in combat | ? | ||||||

The Second Madagascar expedition was a French military intervention which took place in 1894-1895, sealing the conquest of the Merina Kingdom on the island of Madagascar by France. It was the last phase of the Franco-Hova War and followed the First Madagascar expedition of 1883-85.

Background

Madagascar was at the time an independent country, ruled from the capital of Antananarivo by the Merina dynasty from the central highlands.[1] The French invasion was triggered by the refusal of Queen Ranavalona III to accept a protectorate treaty from France,[2] despite the signature of the Franco-Hova Treaty of 1885 following the First Madagascar expedition.[3] Resident-general Charles Le Myre de Vilers broke negotiation and effectively declared war on the Malagasy monarchy.[4]

The expedition

An expeditionary corps was sent under General Jacques Duchesne.[5] First, the harbor of Toamasina on the east coast, and Mahajanga on the west coast, were bombarded and occupied in December 1894 and January 1895 respectively.[6] Some troops were landed, but the main expeditionary force however arrived in May 1895, numbering about 15,000 men, supported by around 6,000 carriers.[7][8] The campaign was to take place during the rainy season, with disastrous consequences for the French expeditionary corps.[9]

As soon as the French landed, revolts erupted here and there against the Merina government of Queen Ranavalona III. The uprisings were variously against the government, slave labor, Christianization (the court had converted to Protestantism in the 1860s).[10]

As the French force advanced towards Antananarivo, they had to build a road along the way.[11] By August 1895, the French were only mid-way at Andriba where there were numerous Malagasy fortifications but only limited fighting.[12] Disease, especially malaria, but also dysentery and typhoid fever, was taking a heavy toll on the French expeditionary corps.[13] The expedition was a medical disaster: about 1/3 of the force died of disease.[14] Altogether, there were 6,000 deaths in the expedition, four-fifths of them French.[15]

The Malagasy Prime Minister and Commander-in-Chief Rainilaiarivony tried to resist at Tsarasaotra on 29 June 1895, and at Andriba on 22 August 1895. He again attacked the Duchesne "flying column" in September, but his elite gunner troops were decimated by the French.[16]

Duchesne had to send a "flying column" from Andriba on 14 September 1895, formed of Algerian and African soldiers as well as marines and accompanied by pack mules, to the capital. They arrived at the end of September.[17] An artillery battery was trained on the royal palace from the heights around the capital, and high-explosive shells were fired on the palace, killing many.[18] The Queen promptly surrendered.[19][20]

In the whole conflict, there were only a few skirmishes, and only 25 French soldiers died from fighting.[21]

Aftermath

The conquest of the island was formalized by the 6 August 1896 vote at the French National Assembly, which resulted in favor of the annexation of Madagascar.[22]

Despite the success of the expedition, the quelling of the sporadic rebellions would take another eight years until 1905, when the island was completely pacified by the French under Joseph Gallieni.[23][24] During that time, insurrections against the Malagasy Christians of the island, missionaries and foreigners were particularly terrible.[25] Queen Ranavalona III was deposed in January 1897 and was exiled to Algiers in Algeria, where she died in 1917.[26]

|

Notes

- ↑ Vichy in the Tropics: Petain's National Revolution in Madagascar, Guadeloupe ... by Eric Jennings p.33

- ↑ Musée de l'Armée exhibit, Paris

- ↑ France overseas: a study of modern imperialism by Herbert Ingram Priestley p.308

- ↑ The Cambridge history of Africa J. D. Fage p.529

- ↑ Musée de l'Armée exhibit, Paris

- ↑ Disease and empire: the health of European troops in the conquest of Africa by Philip D. Curtin p.186

- ↑ Curtin, p.186

- ↑ Priestley p.308

- ↑ Cambridge history of Africa, p.529

- ↑ Curtin, p.187

- ↑ Curtin, p.186

- ↑ Curtin, p.186

- ↑ Curtin, p.186

- ↑ Curtin, p.187

- ↑ Priestley p.308

- ↑ Cambridge history of Africa, p.530

- ↑ Curtin, p.186

- ↑ Cambridge history of Africa, p.530

- ↑ Curtin, p.186

- ↑ Cambridge history of Africa, p.530

- ↑ Curtin, p.186

- ↑ Musée de l'Armée exhibit, Paris

- ↑ Curtin, p.187

- ↑ Jennings p.33

- ↑ Priestley p.309

- ↑ Musée de l'Armée exhibit, Paris

References

- Curtin, Philip D. Disease and empire: the health of European troops in the conquest of Africa by Philip D. Curtin

- Ingram, Priestley Herbert France overseas: a study of modern imperialism