Secession in the United States

In the context of the United States, secession primarily refers to the withdrawal of one or more States from the Union that constitutes the United States; but may loosely refer to leaving a State or territory to form a separate territory or new State, or to the severing of an area from a city or county within a State.

Threats and aspirations to secede from the United States, or arguments justifying secession, have been a feature of the country's politics almost since its birth. Some have argued for secession as a constitutional right and others as from a natural right of revolution. In Texas v. White, the United States Supreme Court ruled unilateral secession unconstitutional, while commenting that revolution or consent of the States could lead to a successful secession.

The most serious attempt at secession was advanced in the years 1860 and 1861 as eleven southern States each declared secession from the United States, and joined together to form the Confederate States of America. This movement collapsed in 1865 with the defeat of Confederate forces by Union armies in the American Civil War.[1]

A 2008 Zogby International poll found that 22% of Americans believed that "any state or region has the right to peaceably secede and become an independent republic".[2] A 2014 Reuters/Ipsos poll showed 24% of Americans supported their state seceding from the union if necessary; 53% opposed the idea. Republicans were somewhat more supportive than Democrats. Respondents cited issues like gridlock, governmental overreach, the Affordable Care Act and a loss of faith in the federal government as reasons for secession.[3]

The American Revolution

The Declaration of Independence states:

We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.—That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed,—That whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it, and to institute new Government, laying its foundation on such principles and organizing its powers in such form, as to them shall seem most likely to effect their Safety and Happiness.[4]

Historian Pauline Maier argues that this narrative asserted "... the right of revolution, which was, after all, the right Americans were exercising in 1776"; and notes that Thomas Jefferson's language incorporated ideas explained at length by a long list of seventeenth-century writers including John Milton, Algernon Sidney, and John Locke and other English and Scottish commentators, all of whom had contributed to the development of the Whig tradition in eighteenth-century Britain.[4]

The right of revolution expressed in the Declaration was immediately followed with the observation that long-practised injustice is tolerated until sustained assaults on the rights of the entire people have accumulated enough force to oppress them;[5] then they may defend themselves.[6][7] This reasoning was not original to the Declaration, but can be found in many prior political writings: Locke's Two Treatises of Government (1690); the Fairfax Resolves of 1774; Jefferson's own Summary View of the Rights of British America; the first Constitution of Virginia, which was enacted five days prior to the Declaration.[8] and Thomas Paine's Common Sense (1776):

Prudence, indeed, will dictate that Governments long established should not be changed for light and transient causes; ... mankind are more disposed to suffer, while Evils are sufferable, than to right themselves by abolishing the Forms ("of Government", editor's addition) to which they are accustomed. But when a long train of abuses and usurpations, pursuing ... a design to reduce them under absolute Despotism, it is their right, it is their duty, to throw off such Government, and to provide new Guards for their future security.[9]

Gordon S. Wood quotes John Adams: "Only repeated, multiplied oppressions placing it beyond all doubt that their rulers had formed settled plans to deprive them of their liberties, could warrant the concerted resistance of the people against their government".[10]

Civil War era political and legal views on secession

Overview

With origins in the question of states' rights the issue of secession was argued in many forums and advocated from time to time in both the North and South in the decades after adopting the Constitution and before the American Civil War. Historian Maury Klein described the contemporary debate: "Was the Republic a unified nation in which the individual states had merged their sovereign rights and identities forever, or was it a federation of sovereign states joined together for specific purposes from which they could withdraw at any time?"[11] He observed that "the case can be made that no result of the [American Civil] war was more important than the destruction, once and for all . . . of the idea of secession".[12]

Historian Forrest McDonald argued that after adopting the Constitution "there were no guidelines, either in theory or in history, as to whether the compact could be dissolved and, if so, on what conditions". However, during "the founding era, many a public figure . . . declared that the states could interpose their powers between their citizens and the power of the federal government, and talk of secession was not unknown." But according to McDonald, to avoid resorting to the violence that had accompanied the Revolution, the Constitution established "legitimate means for constitutional change in the future". In effect, the Constitution "completed and perfected the Revolution".[13]

Whatever the intentions of the Founders, threats of secession and disunion were a constant in the political discourse of Americans preceding the Civil War. Historian Elizabeth R. Varon wrote:

... one word [disunion] contained, and stimulated, their [Americans] fears of extreme political factionalism, tyranny, regionalism, economic decline, foreign intervention, class conflict, gender disorder, racial strife, widespread violence and anarchy, and civil war, all of which could be interpreted as God's retribution for America's moral failings. Disunion connoted the dissolution of the republic—the failure of the Founders' efforts to establish a stable and lasting representative government. For many Americans in the North and the South, disunion was a nightmare, a tragic cataclysm that would reduce them to the kind of fear and misery that seemed to pervade the rest of the world. And yet, for many other Americans, disunion served as the main instrument by which they could achieve their political goals.[14]

Abandoning the Articles of Confederation

In late 1777 the Second Continental Congress approved the Articles of Confederation for ratification by the individual states. The confederation government was administered de facto by the Congress under the provisions of the approved (final) draft of the Articles until they achieved ratification—and de jure status—in early 1781. In 1786 delegates of five states (the Annapolis Convention) called for a convention of delegates in Philadelphia to amend the Articles—which would require unanimous consent of the thirteen states.

The delegates to the Philadelphia Convention convened and deliberated from May to September 1787. Instead of pursuing their official charge they returned a draft (new) Constitution, proposed for constructing and administering a new federal—later also known as "national"—government. They further proposed that the draft Constitution not be submitted to the Congress (where it would require unanimous approval of the states); instead that it be presented directly to the states for ratification in special ratification conventions, and that approval by a minimum of nine state conventions would suffice to adopt the new Constitution and initiate the new federal government; and that only those states ratifying the Constitution would be included in the new government. (For a time, eleven of the original states operated under the Constitution without two non-ratifying states, Rhode Island and North Carolina.) In effect, the delegates proposed to abandon and replace the Articles of Confederation rather than amend them.[lower-alpha 1]

Because the Articles had specified a "perpetual union", various arguments have been offered to explain the apparent contradiction (and presumed illegality) of abandoning one form of government and creating another that did not include the members of the original.[lower-alpha 2] One explanation was that the Articles of Confederation simply failed to protect the vital interests of the individual states. Necessity then, rather than legality, was the practical factor in abandoning the Articles.[16]

According to historian John Ferling, by 1786 the Union under the Articles was falling apart. James Madison of Virginia and Alexander Hamilton of New York—they who joined together to vigorously promote a new Constitution—urged that renewed stability of the Union government was critically needed to protect property and commerce. Both founders were strong advocates for a more powerful central government; they published The Federalist Papers to advocate their cause and became known as the federalists. (Because of his powerful advocacy Madison was later accorded the honorific "Father of the Constitution".)[lower-alpha 3] Ferling wrote:

Rumors of likely secessionist movements were unleashed. There was buzz as well that some states planned to abandon the American Union and form a regional confederacy. America, it was said, would go the way of Europe, and ultimately three or four, or more confederacies would spring up. ... Not only would these confederations be capable of taking steps that were beyond the ability of Congress under the articles, but in private some portrayed such a step in a positive light, in as much as the regional union could adopt constitutions that secured property rights and maintained order.[lower-alpha 4]

Other arguments that justified abandoning the Articles of Confederation pictured the Articles as an international compact between unconsolidated, sovereign states, any one of which was empowered to renounce the compact at will. (This as opposed to a consolidated union that "totally annihilated, without any power of revival" the sovereign states.)[19] The Articles required that all states were obliged to comply with all requirements of the agreement; thus, permanence was linked to compliance.

'Compliance' was typically perceived as a matter of interpretation by each individual state. Emerich de Vattel, a recognized authority on international law, wrote at the time that "Treaties contain promises that are perfect and reciprocal. If one of the allies fails in his engagements, the other may ... disengage himself in his promises, and ... break the treaty."[19] Thus, each state could unilaterally 'secede' from the Articles of Confederation at will; this argument for abandoning the Articles—for its weakness in the face of secession—was used by advocates for the new Constitution and was featured by James Madison in Federalist No. 43.[lower-alpha 5]

Some argued that abandoning the Articles was the same as seceding from the Articles and thus was legal precedent for future secession(s) from the Constitution. St. George Tucker, a jurist in the early republic era, wrote in 1803:

And since the seceding states, by establishing a new constitution and form of federal government among themselves, without the consent of the rest, have shown that they consider the right to do so whenever the occasion may, in their opinion require it, we may infer that the right has not been diminished by any new compact which they may since have entered into, since none could be more solemn or explicit than the first, nor more binding upon the contracting partie[s]."[20]

Others denied that such a precedent was set; constitutional historian Akhil Reed Amar wrote:

The fact that a new union was lawfully formed in the 1780s by secession from the old confederacy did not mean that a new confederacy could be lawfully formed in the 1860s by secession from the old union. ...Writing in 1824, exactly midway between the fall of the Articles of Confederation and the rise of a second self-described American Confederacy, [Chief Justice John] Marshall summarized the issue nicely: "Reference has been made to the political situation of these states, anterior to [the Constitution's] formation. It has been said that they were sovereign, were completely independent, and were connected with each other only by a league. This is true. But, when these allied sovereigns converted their league into a government, when they converted their congress of ambassadors, deputed to deliberate on their common concerns, and to recommend measures of general utility, into a legislature, empowered to enact laws on the most interesting subjects, the whole character in which the states appear underwent a change."[21]

Others argued the opposite of secession; that indeed the new Constitution inherited perpetuity from the language in the Articles and from other actions done prior to the Constitution. Historian Kenneth Stampp explains their view:

Lacking an explicit clause in the Constitution with which to establish the Union's perpetuity, the nationalists made their case, first, with a unique interpretation of the history of the country prior to the Philadelphia Convention; second, with inferences drawn from certain passages of the Constitution; and third, with careful selections from the speeches and writings of the Founding Fathers. The historical case begins with the postulate that the Union is older than the states. It quotes the reference in the Declaration of Independence to "these united colonies", contends that the Second Continental Congress actually called the states into being [i.e., "colonies" no longer], notes the provision for a perpetual Union in the Articles of Confederation, and ends with the reminder that the preamble to the new Constitution gives as one of its purposes the formation of "a more perfect Union".[22]

Adopting the Constitution

Constitutional scholar Akhil Reed Amar argues that the permanence of the Union of the states changed significantly when the U.S. Constitution replaced the Articles of Confederation. This action "signaled its decisive break with the Articles' regime of state sovereignty."[23] By adopting a constitution—rather than a treaty, or a compact, or an instrument of confederacy, etc.—that created a new body of government designed to be senior to the several states, and by approving the particular language and provisions of that new Constitution, the framers and voters made it clear that the fates of the individual states were (severely) changed; and that the new United States was:

Not a "league", however firm; not a "confederacy" or a "confederation"; not a compact on among "sovereign' states"—all these high profile and legally freighted words from the Articles were conspicuously absent from the Preamble and every other operative part of the Constitution. The new text proposed a fundamentally different legal framework.[24]

Patrick Henry adamantly opposed adopting the Constitution because he interpreted its language to replace the sovereignty of the individual states, including that of his own Virginia. He gave his strong voice to the anti-federalist cause in opposition to the federalists led by Madison and Hamilton. Questioning the nature of the proposed new federal government, Henry asked:

The fate ... of America may depend on this. ... Have they made a proposal of a compact between the states? If they had, this would be a confederation. It is otherwise most clearly a consolidated government. The question turns, sir, on that poor little thing—the expression, We, the people, instead of the states, of America. ...[25]

The federalists acknowledged that national sovereignty would be transferred by the new Constitution to the whole of the American people—indeed, regard the expression, "We the people ...". They argued, however, that Henry exaggerated the extent to which a consolidated government was being created and that the states would serve a vital role within the new republic even though their national sovereignty was ending. Tellingly, on the matter of whether states retained a right to unilaterally secede from the United States, the federalists made it clear that no such right would exist under the Constitution.[26]

Amar specifically cites the example of New York's ratification as suggestive that the Constitution did not countenance secession. Anti-federalists dominated the Poughkeepsie Convention that would ratify the Constitution. Concerned that the new compact might not sufficiently safeguard states' rights, the anti-federalists sought to insert into the New York ratification message language to the effect that "there should be reserved to the state of New York a right to withdraw herself from the union after a certain number of years."[27] The Madison federalists opposed this, with Hamilton, a delegate at the Convention, reading aloud in response a letter from James Madison stating: "the Constitution requires an adoption in toto, and for ever" [emphasis added]. Hamilton and John Jay then told the Convention that in their view, reserving "a right to withdraw [was] inconsistent with the Constitution, and was no ratification."[27] The New York convention ultimately ratified the Constitution without including the "right to withdraw" language proposed by the anti-federalists.

Amar explains how the Constitution impacted on state sovereignty:

In dramatic contrast to Article VII–whose unanimity rule that no state can bind another confirms the sovereignty of each state prior to 1787 – Article V does not permit a single state convention to modify the federal Constitution for itself. Moreover, it makes clear that a state may be bound by a federal constitutional amendment even if that state votes against the amendment in a properly convened state convention. And this rule is flatly inconsistent with the idea that states remain sovereign after joining the Constitution, even if they were sovereign before joining it. Thus, ratification of the Constitution itself marked the moment when previously sovereign states gave up their sovereignty and legal independence.[28]

Donald Livingston has written that the Founders themselves held that "the states were republics, but the central government was not," and as such maintained the right to reclaim their sovereignty from "a central government limited to foreign affairs, declaring war, and regulating commerce."[29]

Natural right of revolution versus right of secession

Debates on the legality of secession often looked back to the example of the American Revolution and the Declaration of Independence. Law professor Daniel Farber defined what he considered the borders of this debate:

What about the original understanding? The debates contain scattered statements about the permanence or impermanence of the Union. The occasional reference to the impermanency of the Constitution are hard to interpret. They might have referred to a legal right to revoke ratification. But they equally could have referred to an extraconstitutional right of revolution, or to the possibility that a new national convention would rewrite the Constitution, or simply to the factual possibility that the national government might break down. Similarly, references to the permanency of the Union could have referred to the practical unlikelihood of withdrawal rather than any lack of legal power. The public debates seemingly do not speak specifically to whether ratification under Article VII was revocable.[30]

In the public debate over the Nullification Crisis the separate issue of secession was also discussed. James Madison, often referred to as "The Father of the Constitution", strongly opposed the argument that secession was permitted by the Constitution.[31] In a March 15, 1833, letter to Daniel Webster (congratulating him on a speech opposing nullification), Madison discussed "revolution" versus "secession":

I return my thanks for the copy of your late very powerful Speech in the Senate of the United S. It crushes "nullification" and must hasten the abandonment of "Secession". But this dodges the blow by confounding the claim to secede at will, with the right of seceding from intolerable oppression. The former answers itself, being a violation, without cause, of a faith solemnly pledged. The latter is another name only for revolution, about which there is no theoretic controversy.[32]

Thus Madison affirms an extraconstitutional right to revolt against conditions of "intolerable oppression"; but if the case cannot be made (that such conditions exist), then he rejects secession—as a violation of the Constitution.

During the crisis, President Andrew Jackson, published his Proclamation to the People of South Carolina, which made a case for the perpetuity of the Union; plus, he provided his views re the questions of "revolution" and "secession":[33]

But each State having expressly parted with so many powers as to constitute jointly with the other States a single nation, cannot from that period possess any right to secede, because such secession does not break a league, but destroys the unity of a nation, and any injury to that unity is not only a breach which would result from the contravention of a compact, but it is an offense against the whole Union. [emphasis added] To say that any State may at pleasure secede from the Union, is to say that the United States are not a nation because it would be a solecism to contend that any part of a nation might dissolve its connection with the other parts, to their injury or ruin, without committing any offense. Secession, like any other revolutionary act, may be morally justified by the extremity of oppression; but to call it a constitutional right, is confounding the meaning of terms, and can only be done through gross error, or to deceive those who are willing to assert a right, but would pause before they made a revolution, or incur the penalties consequent upon a failure.[34]

Some twenty-eight years after Jackson spoke, President James Buchanan gave a different voice—one much more accommodating to the views of the secessionists and the 'slave' states—in the midst of the pre-War secession crisis. In his final State of the Union address to Congress, on December 3, 1860, he acknowledged his view that the South, "after having first used all peaceful and constitutional means to obtain redress, would be justified in revolutionary resistance to the Government of the Union"; but he also drew his apocalyptic vision of the results to be expected from secession:[35]

In order to justify secession as a constitutional remedy, it must be on the principle that the Federal Government is a mere voluntary association of States, to be dissolved at pleasure by any one of the contracting parties. [emphasis added] If this be so, the Confederacy [here referring to the existing Union] is a rope of sand, to be penetrated and dissolved by the first adverse wave of public opinion in any of the States. In this manner our thirty-three States may resolve themselves into as many petty, jarring, and hostile republics, each one retiring from the Union without responsibility whenever any sudden excitement might impel them to such a course. By this process a Union might be entirely broken into fragments in a few weeks which cost our forefathers many years of toil, privation, and blood to establish.[36]

Alien and Sedition Acts

In response to the 1798 Alien and Sedition Acts—advanced by the Federalist Party—John Taylor of the Virginia House of Delegates spoke out, urging Virginia to secede from the United States. He argued—as one of many vociferous responses by the Jeffersonian Republicans—the sense of the Kentucky and Virginia Resolutions, adopted in 1798 and 1799, which reserved to those States the rights of secession and interposition (nullification).[37]

Thomas Jefferson, while sitting as Vice President of the United States in 1799, wrote to James Madison of his conviction in "a reservation of th[ose] rights resulting to us from these palpable violations [the Alien and Sedition Acts]" and, if the federal government did not return to

"the true principles of our federal compact", [he was determined to] "sever ourselves from that union we so much value, rather than give up the rights of self government which we have reserved, and in which alone we see liberty, safety and happiness."[emphasis added][38]

Here Jefferson is arguing in a radical voice (and in a private letter) that he would lead a movement for secession; but it is unclear whether he is arguing for "secession at will" or for "revolution" on account of "intolerable oppression" (see above), or neither. Either way, some historians conclude that his language and acts were broaching the legal edges of treason. Jefferson secretly wrote (one of) the Kentucky Resolutions, which was done—again—while he was holding the office of Vice President. His biographer Dumas Malone argued that, had his actions become known at the time, Jefferson's participation might have gotten him impeached for (charged with) treason.[39] In writing the first Kentucky Resolution, Jefferson warned that, "unless arrested at the threshold," the Alien and Sedition Acts would "necessarily drive these states into revolution and blood." Historian Ron Chernow says of this "he wasn't calling for peaceful protests or civil disobedience: he was calling for outright rebellion, if needed, against the federal government of which he was vice president." Jefferson "thus set forth a radical doctrine of states' rights that effectively undermined the constitution."[40]

Jeffersonian Republicans were not alone in claiming "reserved rights" against the federal government. Contributing to the rancorous debates during the War of 1812, Founding Father Gouverneur Morris of Pennsylvania and New York—a Federalist, a Hamilton ally and a primary author of the Constitution who advanced the concept that Americans were citizens of a single Union of the states—was persuaded to claim that "secession, under certain circumstances, was entirely constitutional."[41]

New England Federalists and the Hartford Convention

The election of 1800 showed Jefferson's Democratic-Republican Party on the rise and the Federalists declining. The Federalists felt threatened by initiatives taken by their opponents. They viewed Jefferson's unilateral purchase of the Louisiana territory as violating foundational agreements between the original thirteen states—Jefferson transacted the purchase in secret and refused to seek the approval of Congress. The new lands anticipated several future western states that would be—the Federalists supposed—populated by emigrants from the eastern states who likely would be dominated by the Democratic-Republicans. The impeachment of John Pickering, a Federalist district judge, by the Jeffersonian dominated Congress and similar attacks on Pennsylvania state officials by the Democratic-Republican legislature added to the Federalists' alarm. By 1804, their national leadership was decimated and their viable base was reduced to the states of Massachusetts, Connecticut, and Delaware.[42]

Timothy Pickering of Massachusetts and a few Federalists envisioned creating a separate New England confederation, possibly combining with lower Canada to form a new pro-British nation. Historian Richard Buell, Jr., characterizes these separatist musings:

Most participants in the explorations—it can hardly be called a plot since it never took concrete form—focused on the domestic obstacles to consummating their fantasy. These included lack of popular support for such a scheme in the region. ... The secessionist movement of 1804 was more of a confession of despair about the future than a realistic proposal for action.[43]

The Embargo Act of 1807 was seen as a threat to the economy of Massachusetts and in May 1808 the state legislature debated how the state should respond. These debates generated isolated references to secession, but no definite plot materialized.[44]

Federalist party members convened the Hartford Convention on December 15, 1814; they addressed their opposition to the continuing war with England and the domination of the federal government by the 'Virginia dynasty'. Twenty six delegates attended—Massachusetts sent 12, Connecticut seven, and Rhode Island four; New Hampshire and Vermont declined but two counties each from those states sent delegates.[45] Historian Donald R. Hickey noted:

Despite pleas in the New England press for secession and a separate peace, most of the delegates taking part in the Hartford Convention were determined to pursue a moderate course. Only Timothy Bigelow of Massachusetts apparently favored extreme measures, and he did not play a major role in the proceedings.[45]

The final report addressed issues related to the war and state defense; and it recommended several amendments to the Constitution dealing with "the overrepresentation of white southerners in Congress, the growing power of the West, the trade restrictions and the war, the influence of foreigners (like Albert Gallatin), and the Virginia dynasty's domination of national politics."[46][47]

Massachusetts and Connecticut endorsed the report, but the war ended as the delegates were returning to Washington, effectively quashing any good impact the report might have had. Generally, the Hartford Convention was a "victory for moderation", but the timing of events caused the convention to be castigated (by the Jeffersonians) as "a synonym for disloyalty and treason"; all which became a major factor in the sharp decline of the Federalist Party.[48]

Abolitionists for secession

By the late 1830s tensions between north and south, already aggravated over tariff disputes, begin to rise ominously over slavery and related issues. Many northerners, especially New Englanders, saw themselves as political victims of conspiracies between slaveholders and western expansionists. They viewed the movements to annex Texas and to make war on Mexico as fomented by slaveholders bent on dominating western expansion—and thereby the national destiny—with 'slave' states and a 'slave' national economy.

Historian Joel Sibley wrote of the beliefs held by some leaders in New England:

Texas annexation, the abolitionist Benjamin Lundy argued when the issue first arose in 1836, was "a long premeditated crusade—set on foot by slaveholders, land speculators, etc., with the view of reestablishing, extending, and perpetuating the system of slavery and the slave trade"[.] John Quincy Adams had made a similar argument on the floor of the House of Representatives then. Other expressions of the same theme—or accusation—had been heard throughout the decade that followed, whenever Texas was mentioned.[50]

Voices demanding separation from the south were beginning (again). In The Liberator of May 1844 with his "Address to the Friends of Freedom and Emancipation in the United States," William Lloyd Garrison called for disunion (secession). Garrison wrote: the Constitution was created "at the expense of the colored population of the country"; southerners were dominating the nation—especially representation in Congress—because of the Three-Fifths Compromise; now it was time "to set the captive free by the potency of truth" and to "secede from the government".[51] Coincidentally, the New England Anti-Slavery Convention endorsed the principles of disunion by a vote of 250–24.[52]

From 1846, after introduction of the Wilmot Proviso into the public debate, talk in favor of secession shifted to southern voices. Southern leaders' increasing perceptions of helplessness in confronting a powerful political group attacking their interests (and survival) were reminiscent of Federalist alarms at the beginning of the century.

South Carolina

During the presidential term of Andrew Jackson, South Carolina had its own semi-secession movement due to the 1828 "Tariff of Abomination" which threatened both South Carolina's economy and the Union. Andrew Jackson also threatened to send federal troops to put down the movement and to hang the leader of the secessionists from the highest tree in South Carolina. Also due to this, Jackson's vice president, John C. Calhoun, who supported the movement and wrote the essay "The South Carolina Exposition and Protest", became the first US vice-president to resign. On May 1, 1833, Jackson wrote of nullification, "the tariff was only a pretext, and disunion and southern confederacy the real object. The next pretext will be the negro, or slavery question."[53] South Carolina also threatened to secede in 1850 over the issue of California's statehood. It became the first state to declare its secession from the Union on December 20, 1860, with the Declaration of the Immediate Causes Which Induce and Justify the Secession of South Carolina from the Federal Union and later joined with the other southern states in the Confederacy.

Confederate States of America

- See main articles Origins of the American Civil War, Confederate States of America and American Civil War.

The most famous secession movement was the case of the Southern states of the United States. Secession from the United States was accepted in eleven states (and failed in two others). The seceding states joined together to form the Confederate States of America (CSA). The eleven states of the CSA, in order of secession, were: South Carolina (seceded December 20, 1860), Mississippi (seceded January 9, 1861), Florida (seceded January 10, 1861), Alabama (seceded January 11, 1861), Georgia (seceded January 19, 1861), Louisiana (seceded January 26, 1861), Texas (seceded February 1, 1861), Virginia (seceded April 17, 1861), Arkansas (seceded May 6, 1861), North Carolina (seceded May 20, 1861), and Tennessee (seceded June 8, 1861). Secession was declared by its supporters in Missouri and Kentucky, but did not become effective as it was opposed by their pro-Union state governments. This secession movement brought about the American Civil War. The position of the Union was that the Confederacy was not a sovereign nation—and never had been, but that "the Union" was always a single nation by intent of the states themselves, from 1776 onward—and thus that a rebellion had been initiated by individuals. Historian Bruce Catton described President Abraham Lincoln's April 15, 1861, proclamation after the attack on Fort Sumter, which defined the Union's position on the hostilities:

After reciting the obvious fact that "combinations too powerful to be suppressed" by ordinary law courts and marshalls had taken charge of affairs in the seven secessionist states, it announced that the several states of the Union were called on to contribute 75,000 militia "...to suppress said combinations and to cause the laws to be duly executed." ... "And I hereby command the persons composing the combinations aforesaid to disperse, and retire peacefully to their respective abodes within twenty days from this date.[54]

Dubious legality of unilateral secession

The Constitution does not directly mention secession.[55] The legality of secession was hotly debated in the 19th century, with Southerners often claiming and Northerners generally denying that states have a legal right to unilaterally secede.[56] The Supreme Court has consistently interpreted the Constitution to be an "indestructible" union.[55] There is no legal basis a state can point to for unilaterally seceding.[57] Many scholars hold that the Confederate secession was blatantly illegal. The Articles of Confederation explicitly state the Union is "perpetual"; the U.S. Constitution declares itself an even "more perfect union" than the Articles of Confederation.[58] Other scholars, while not necessarily disagreeing that the secession was illegal, point out that sovereignty is often de facto an "extralegal" question. Had the Confederacy won, any illegality of its actions under U.S. law would have been rendered irrelevant, just as the undisputed illegality of American rebellion under the British law of 1775 was rendered irrelevant. Thus, these scholars argue, the illegality of unilateral secession was not firmly de facto established until the Union won the Civil War; in this view, the legal question was resolved at Appomattox.[56][59]

Supreme Court rulings

Texas v. White[58] was argued before the United States Supreme Court during the December 1868 term. Chief Justice Salmon P. Chase read the Court's decision, on April 15, 1869.[60] Australian Professors Peter Radan and Aleksandar Pavkovic write:

Chase, [Chief Justice], ruled in favor of Texas on the ground that the Confederate state government in Texas had no legal existence on the basis that the secession of Texas from the United States was illegal. The critical finding underpinning the ruling that Texas could not secede from the United States was that, following its admission to the United States in 1845, Texas had become part of "an indestructible Union, composed of indestructible states." In practical terms, this meant that Texas has never seceded from the United States.[61]

However, the Court's decision recognized some possibility of the divisibility "through revolution, or through consent of the States".[61][62]

In 1877, the Williams v. Bruffy[63] decision was rendered, pertaining to civil war debts. The Court wrote regarding acts establishing an independent government that "The validity of its acts, both against the parent state and the citizens or subjects thereof, depends entirely upon its ultimate success; if it fail to establish itself permanently, all such acts perish with it; if it succeed and become recognized, its acts from the commencement of its existence are upheld as those of an independent nation."[61][64]

The Union as a sovereign state

Historian Kenneth Stampp notes that a historical case against secession had been made that argued that "the Union is older than the states" and that "the provision for a perpetual Union in the Articles of Confederation" was carried over into the Constitution by the "reminder that the preamble to the new Constitution gives us one of its purposes the formation of 'a more perfect Union'."[22] Concerning the White decision Stampp wrote:

In 1869, when the Supreme Court, in Texas v. White, finally rejected as untenable the case for a constitutional right of secession, it stressed this historical argument. The Union, the Court said, "never was a purely artificial and arbitrary relation." Rather, "It began among the Colonies. ...It was confirmed and strengthened by the necessities of war, and received definite form, and character, and sanction from the Articles of Confederation."[22]

Texas secession from Mexico

The Republic of Texas successfully seceded from Mexico in 1836 (this, however took the form of outright rebellion against Mexico, and claimed no warrant under the Mexican Constitution to do so). Mexico refused to recognize its revolted province as an independent country, but the major nations of the world did recognize it. In 1845, Congress admitted Texas as a state. The documents governing Texas' accession to the United States of America do not mention any right of secession—although they did raise the possibility of dividing Texas into multiple states inside the Union. Mexico warned that annexation meant war and the Mexican–American War followed in 1846.[65]

Partition of a state

Article IV, Section. 3, Clause 1 of the United States Constitutions provides:

- New States may be admitted by the Congress into this Union; but no new States shall be formed or erected within the Jurisdiction of any other State; nor any State be formed by the Junction of two or more States, or parts of States, without the Consent of the Legislatures of the States concerned as well as of the Congress.

The separation referred to is not secession but partition. Some of the movements to partition states have incorrectly identified themselves as "secessionist" movements.

Of the new states admitted to the Union by Congress, three were set off from already existing states,[66] while one was established upon land claimed by an existing state after existing for several years as a de facto independent republic. They are:

- Vermont was admitted as a new state in 1791[67] after the legislature of New York ceded its claim to the region in 1790. New York's claim that Vermont (also known as the New Hampshire Grants) was legally a part of New York was and remains a matter of disagreement. King George III, ruled in 1764 that the region belonged to the Province of New York.

- Kentucky was a part of Virginia until it was admitted as a new state in 1792[68] with the consent of the legislature of Virginia in 1789.[69]

- Maine was a part of Massachusetts until it was admitted as a new state in 1820[70] after the legislature of Massachusetts consented in 1819.[69]

- West Virginia was a part of Virginia until it was admitted as a new state in 1863[71] after the General Assembly of the Restored Government of Virginia consented in 1862.[72] The question of whether the legislature of Virginia consented is controversial, as Virginia was one of the Confederate states. However, antisecessionist Virginians formed a government in exile, which was recognized by the United States and approved the state's partition. Later, by its ruling in Virginia v. West Virginia (1871), the Supreme Court implicitly affirmed that the breakaway Virginia counties did have the proper consents required to become a separate state.[73]

Many proposals to partition U.S. states have been unsuccessful.

1980s–present efforts

The late 20th and early 21st centuries have seen examples of local and state secession movements. All such movements to create new states have failed. The formation in 1971 of the Libertarian Party and its national platform affirmed the right of states to secede on three vital principles: "We shall support recognition of the right to secede. Political units or areas which do secede should be recognized by the United States as independent political entities where: (1) secession is supported by a majority within the political unit, (2) the majority does not attempt suppression of the dissenting minority, and (3) the government of the new entity is at least as compatible with human freedom as that from which it seceded."[74]

City secession

There was an attempt by Staten Island to break away from New York City in the late 1980s and early 1990s, leading to a 1993 referendum, in which 65% voted to secede. Implementation was blocked in the State Assembly by assertions that the state's constitution required a "home rule message" from New York City.[75]

The San Fernando Valley lost a vote to separate from Los Angeles in 2002 but has seen increased attention to its infrastructure needs. Despite the majority (55%) of the valley within the L.A. city limits voting for secession, the city council unanimously voted to block the partition of the valley north of Mulholland Drive. If the San Fernando Valley became a city, it would be the seventh largest in the United States, with over one million people.

Other attempted city secession drives include Killington, Vermont, which has voted twice (2005 and 2006) to join New Hampshire; the community of Miller Beach, Indiana, originally a separate incorporated community, to split from the city of Gary in 2007; Northeast Philadelphia to split from the city of Philadelphia; and the rejection of annexation of what was the unincorporated area of West Indio from Indio, California.

A portion of the town of Calabash, North Carolina voted to secede from the town in 1998 after receiving permission for a referendum on the issue from the state of North Carolina. Following secession, the area incorporated itself as the town of Carolina Shores. Despite the split, the towns continue to share fire and emergency services.[76]

County secession

In U.S. history, many counties have been divided, often for routine administrative convenience, although sometimes at the request of a majority of the residents. During the 20th century, over 1,000 county secession movements existed, but since the 1950s only three have succeeded: La Paz County, Arizona, broke off from Yuma County and the Cibola County, New Mexico, effort both occurred in the early 1980s, while during 1998–2001 there was a transition by Broomfield, Colorado, to become a separate jurisdiction from four different counties.

Prior to these, the last county created in the U.S. was Menominee County, Wisconsin, in 1959. The problem with Menominee County was an act to replace the Menominee Indian Reservation from 1961 to its restoration in 1973. Another case is Osage County, Oklahoma, when the county was meant to replace the Osage tribal sovereignty, and the BIA declaration of it being a "mineral estate" not a sovereign tribal group nor the state's only Indian reservation in 1997.

The High Desert County, California, plan to split the northern half of Los Angeles and the eastern half of Kern counties, was approved by the California state government in 2006, but was never officially declared in force. The state rejected the approval due to inaction of any establishment of county government in 2009.

In 2010, southern Cook County, Illinois petitioned to create "Lincoln County", to protest the dominance of Chicago. The county's possible largest city would be Calumet City, Illinois, and only 600,000 out of 5.03 million Cook County residents live south of Chicago.

In Arizona, a movement called for the southeastern portion of Maricopa County, Arizona to secede and establish "Mesa County" for Mesa in order to complain about the county government mainly focusing on Phoenix instead of the entire county.

State secession

Some state movements seek secession from the United States itself and the formation of a nation from one or more states.

- Alaska: In November 2006, the Alaska Supreme Court held in the case [Kohlhaas v. State] that secession was illegal, and refused to permit an initiative to be presented to the people of Alaska for a vote. The Alaskan Independence Party remains a factor in state politics, and Walter Hickel, a member of the party, was Governor from 1990 to 1994.[77]

- California: This was discussed by involved grassroots movement parties and small activist groups calling for the state to secede from the union, they met in a pro-secessionist meeting in Sacramento on April 15, 2010, to discuss advancing the matter.[78] In 2015, a Political Action Committee called the Yes California Independence Committee formed to advocate California's independence from the United States.[79] On January 8, 2016, the California Secretary of State's office confirmed that a political body called the California National Party filed the appropriate paperwork to begin qualifying as a political party.[80][81] The California National Party, whose primary objective is California independence, ran a candidate for State Assembly in the June 7, 2016 primary.[82] On November 9, 2016, after Donald Trump's win in the presidential election, residents of the state caused #calexit to trend on Twitter, wanting out of the country due to his win; they argue that they have the 6th largest economy in the world, and more residents than any other state in the union.[83]

- Florida: The mock 1982 secessionist protest[84] by the Conch Republic in the Florida Keys resulted in an ongoing source of local pride and tourist amusement. In 2015, right-wing activist Jason Patrick Sager[85] called for Florida to secede.[86][87]

- Georgia: On April 1, 2009, the Georgia State Senate passed a resolution, 43–1, that asserted the right of states to nullify federal laws under some circumstances. The resolution also asserted that if Congress, the president, or the federal judiciary took certain steps, such as establishing martial law without state consent, requiring some types of involuntary servitude, taking any action regarding religion or restricting freedom of political speech, or establishing further prohibitions of types or quantities of firearms or ammunition, the constitution establishing the United States government would be considered nullified and the union would be dissolved.[88]

- Hawaii: The Hawaiian sovereignty movement has a number of active groups that have won some concessions from the state of Hawaii, including the offering of H.R. 258 in March 2011, which removes the words "Treaty of Annexation" from a statute. It has passed a committee recommendation 6–0 thus far.[89]

- Montana: With the decision of the Supreme Court of the United States to hear District of Columbia v. Heller in late 2007, an early 2008 movement began in Montana involving at least 60 elected officials addressing potential secession if the Second Amendment were interpreted not to grant an individual right, citing its compact with the United States of America.[90]

- New Hampshire: On September 1, 2012, "The New Hampshire Liberty Party was formed to promote independence from the federal government and for the individual."[91] The Free State Project is another NH based movement that has considered secession to increase liberty. On July 23, 2001, founder of the FSP, Jason Sorens, published "Announcement: The Free State Project", in The Libertarian Enterprise stating, "Even if we don't actually secede, we can force the federal government to compromise with us and grant us substantial liberties. Scotland and Quebec have both used the threat of secession to get large subsidies and concessions from their respective national governments. We could use our leverage for liberty."[92]

- Oregon: Following the 2016 U.S Elections, Protests began in the State, particularly in Portland. The Oregon Secession Act was sent to the ballot for 2018, however, a day later it was withdrawn. The leaders of the Oregon Org. Said they would possibly put it back in once it was all calm.

- South Carolina: In May 2010 a group formed that called itself the Third Palmetto Republic, a reference to the fact that the state claimed to be an independent republic twice before: once in 1776 and again in 1860. The group models itself after the Second Vermont Republic, and says its aims are for a free and independent South Carolina, and to abstain from any further federations.. In 2015, The South Carolina Secessionist Party was founded. It is a party that seeks to establish South Carolina as its Own independent nation

- Texas Secession Movement: The group Republic of Texas generated national publicity for its controversial actions in the late 1990s.[93] A small group still meets.[94] In April 2009, Rick Perry, the Governor of Texas, raised the issue of secession in disputed comments during a speech at a Tea Party protest saying "Texas is a unique place. When we came into the union in 1845, one of the issues was that we would be able to leave if we decided to do that ... My hope is that America and Washington in particular pays attention. We've got a great union. There's absolutely no reason to dissolve it. But if Washington continues to thumb their nose at the American people, who knows what may come of that."[95][96][97][98]

- Vermont: The Second Vermont Republic, founded in 2003, is a loose network of several groups that describes itself as "a nonviolent citizens' network and think tank opposed to the tyranny of Corporate America and the U.S. government, and committed to the peaceful return of Vermont to its status as an independent republic and more broadly the dissolution of the Union."[99][100] Its "primary objective is to extricate Vermont peacefully from the United States as soon as possible."[101] They have worked closely with the Middlebury Institute created from a meeting sponsored in Vermont in 2004.[102][103] On October 28, 2005, activists held the Vermont Independence Conference, "the first statewide convention on secession in the United States since North Carolina voted to secede from the Union on May 20, 1861".[101] They also participated in the 2006 and 2007 Middlebury-organized national secessionist meetings that brought delegates from over a dozen groups.[104][105][106][107][108]

- Republic of Lakotah: Some members of the Lakota people of Montana, Wyoming, Nebraska, North Dakota, and South Dakota created the Republic to assert the independence of a nation that was always sovereign and did not willingly join the United States; therefore they do not consider themselves technically to be secessionists.[109]

- In the aftermath of the 2012 presidential election, secession petitions pertaining to all fifty states were filed through the White House We the People petition website.[110][111]

Regional secession

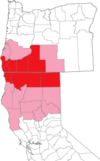

- Pacific Northwest: Cascadia: There have been repeated attempts to form a Bioregional Democracy Cascadia in the northwest. The core of Cascadia would be made up through the secession of the states of Washington, Oregon and the Canadian province of British Columbia, while some supporters of the movement support portions of Northern California, Southern Alaska, Idaho and Montana joining, to define its boundaries along ecological, cultural, economic and political boundaries.[112][113][114][115][116]

- Northwest Front: The Northwest Front is a white separatist movement that is advocating for the formation of an independent sovereign republic in the Pacific Northwestern states of Washington, Oregon, Idaho and western Montana, that will serve as a "white homeland" for white people throughout the world. The nationalist movement is led by Harold Covington.[117]

- League of the South: The group seeks "a free and independent Southern republic"[118] made up of the former Confederate States of America.[119] It operated a short-lived Southern Party supporting the right of states to secede from the Union or to legally nullify federal laws.[120]

Territory secession

- Puerto Rico: The Puerto Rican independence movement traces its origins to the Taíno rebellion of 1511. Recent resolutions aimed at giving the island the right to self-determination include a draft from the U.N. Special Committee of the 24 on Decolonization in 2009 and the Puerto Rico Democracy Act of 2010.

- Philippine Islands: the Philippines is the only territory among both states and present territories that has succeeded in attaining full independence from the union.

Cultural reference

The secession-from-Massachusetts movement of the late 1970s was reflected in Nathaniel Benchley's comic novel of the time, Sweet Anarchy.[121]

See also

- 51st state

- American Redoubt

- Kirkpatrick Sale

- List of active autonomist and secessionist movements in the United States

- List of U.S. state partition proposals

- Northwest Territorial Imperative

- Ordinance of Secession

- Southern nationalism

- Submissionist

- Thomas Naylor

Notes

- ↑ St. George Tucker wrote "The dissolution of these systems [any confederacy of states] happens, when all the confederates by mutual consent, or some of them, voluntarily abandon the confederacy, and govern their own states apart; or a part of them form a different league and confederacy among each other, and withdraw themselves from the confederacy with the rest. Such was the proceeding on the part of those of the American states which first adopted the present constitution of the United States . . . leaving the states of Rhode Island and North Carolina, both of which, at first, rejected the new constitution, to themselves.[15]

- ↑ Tucker wrote that this was an evident breach of the Articles of Confederation; because they stipulated that "those 'articles should be inviolably observed by every state, and that union should be perpetual; nor should any alteration at any time thereafter be made in any of them, unless such alterations be agreed to in the congress of the United States, and be afterwards confirmed by the legislatures of every state.'" (Tucker quoting from the Articles of Confederation). "Yet the seceding states, as they may not be improperly termed, did not hesitate, as soon as nine states had ratified the new constitution, to supersede the former federal government and establish a new form, more consonant to their opinion of what was necessary to the preservation and prosperity of the federal union."[15]

- ↑ Of Madison, Ferling wrote that he was "resolute about protecting the propertied class from what he believed were the democratic excesses of the American Revolution and, at the same time, guarding Southern interests, which to a considerable extent meant preserving the well being of slaveholders against a Northern majority." Of Hamilton, Ferling wrote, "His principal aim, according to his biographer Forrest McDonald, was to lay groundwork for enhanced Congressional authority over commerce."[17]

- ↑ Ferling notes that John Jay wrote to George Washington that "Errors in our national Government ... threaten the Fruit we expected from our 'Tree of Liberty'. Ferling wrote of Henry Lee that he spoke of the "contempt with which America was held in Europe" (Ferling's words) and the dangers that the country's "degrading supiness" (Lee's words) presented to preservation of the nation.[18]

- ↑ From Federalist 43: A compact between independent sovereigns, founded on ordinary acts of Legislative authority, can pretend to no higher validity than a league or treaty between the parties. It is an established doctrine on the subject of treaties, that all the Articles are mutually conditions of each other; that a breach of any one Article is a breach of the whole treaty; and that a breach, committed by either of the parties, absolves the others, and authorizes them, if they please, to pronounce the compact violated and void. Should it unhappily be necessary to appeal to these delicate truths for a justification for dispensing with the consent of particular States to a dissolution of the federal pact, will not the complaining parties find it a difficult task to answer the multiplied and important infractions with which they may be confronted?[19]

Citations

- ↑ Gienapp 2002.

- ↑ "One in Five Americans Believe States Have the Right to Secede". Middlebury Institute. Retrieved September 16, 2015.

- ↑ "One in four Americans says they support seceding from the U.S.A. in wake of failed Scottish vote for independence". Daily Mail. Reuters. September 19, 2014. Retrieved September 16, 2015.

- 1 2 Maier 1997, p. 135.

- ↑ J Jayne, Allen, Op. Cit., pp. 45, 46, 48

- ↑ Eidelberg 1976, p. 24.

- ↑ J Jayne, Allen, Op. Cit., p. 128

- ↑ "Creating the Declaration of Independence – Train of Abuses: Antecedent Documents". Creating the United States. Library of Congress. Retrieved February 16, 2015. (includes: Draft of the Virginia Constitution, 1776, Common Sense, 1776, A Summary View of the Rights of British America, 1774, Fairfax County Resolves, 1774, Two Treatises of Government, 1690)

- ↑ "Exhibition Home". Creating the United States. Library of Congress. Archived from the original on 2010-06-06.

- ↑ Wood 1969, p. 40.

- ↑ Klein 1997, pp. 32–33.

- ↑ Klein 1997, p. xii.

- ↑ McDonald 1985, pp. 281–82.

- ↑ Varon 2008, pp. 1–2.

- 1 2 Wilson, p. 84.

- ↑ Amar 2005, p. 30.

- ↑ Ferling 2003, pp. 273–74.

- ↑ Ferling 2003, p. 274.

- 1 2 3 Amar 2005, p. 31: The quoted material is from Blackstone's "Commentaries".

- ↑ Wilson, pp. 85–86.

- ↑ Amar 2005, p. 39: quoting Gibbons v. Ogden, 22 U.S. (9 Wheat.) 1 (1824).

- 1 2 3 Stampp 1978, p. 6.

- ↑ Amar 2005, pp. 29–32.

- ↑ Amar 2005, p. 33.

- ↑ Amar 2005, p. 35.

- ↑ Amar 2005, pp. 35–36.

- 1 2 Amar, Akhil Reed (September 19, 2005). "Conventional Wisdom". New York Times. Archived from the original on May 29, 2015. Retrieved May 29, 2015.

- ↑ Amar, Akhil Reed. "David C. Baur Lecture: Abraham Lincoln And The American Union".

- ↑ Livingston, Donald, editor (2012). Rethinking the American Union for the Twenty-First Century. Gretna, LA: Pelican Publishing Company. p. 17. ISBN 978-1-58980-957-4.

- ↑ Farber 2003, p. 87.

- ↑ Ketcham 1990, pp. 644–46.

- ↑ "Volume 1, Chapter 3, Document 14: James Madison to Daniel Webster". The Founder's Constitution. University of Chicago. March 18, 1833. Retrieved September 16, 2015.

- ↑ Remini 1984, p. 21.

- ↑ "President Jackson's Proclamation Regarding Nullification". The Avalon Project. Yale Law School. December 10, 1832. Retrieved September 16, 2015.

- ↑ Farber 2003, pp. 87–88.

- ↑ Buchanan, James (December 3, 1860). "State of the Union Address". Teaching American History. Retrieved September 16, 2015.

- ↑ Stromberg 1982, p. 42.

- ↑ Smith 1995, p. 1119.

- ↑ Chernow 2004, p. 586.

- ↑ Chernow 2004, p. 587.

- ↑ McDonald 1985, p. 281: (citing Morris, "Address to the People of the State of New York" (1814), et al.)

- ↑ Buel 2005, pp. 22–23.

- ↑ Buel 2005, p. 23.

- ↑ Buel 2005, pp. 44–58.

- 1 2 Hickey 1997, p. 233.

- ↑ "Amendments to the Constitution Proposed by the Hartford Convention : 1814". The Avalon Project. Retrieved September 16, 2015.

- ↑ Hickey 1997, pp. 233–34.

- ↑ Hickey 1997, p. 234.

- ↑ Cain 1995, p. 115.

- ↑ Sibley 2005, p. 117.

- ↑ Mayer 1998, p. 327.

- ↑ Mayer 1998, p. 328.

- ↑ Meacham 2009, p. 247.

- ↑ Catton 1961, pp. 327–28.

- 1 2 DeRusha, Jason. "Good Question: Can A State Secede From The Union?". CBS Minnesota. Retrieved 26 September 2016.

- 1 2 Zurcher, Anthony (22 June 2016). "EU referendum: How is the US (not) like the EU?". BBC News. Retrieved 26 September 2016.

- ↑ Cohen, Adam. "Can Texas Really Secede from the Union? Not Legally". Time. Retrieved 26 September 2016.

- 1 2 ussc|74|700|1868

- ↑ Pattani, Aneri (24 June 2016). "Can Texas Legally Secede From the United States?". The Texas Tribune. Retrieved 26 September 2016.

- ↑ Texas v. White.

- 1 2 3 Pavković & Radan 2007, p. 222.

- ↑ "Texas v. White 74 U.S. 700 {1868}". Legal Information Institute. Cornell University Law School. Retrieved September 16, 2015.

- ↑ ussc|96|176|1877

- ↑ "Williams vs. Bruffy 96 U.S. 176 (1877)". Justia U.S. Supreme Court. Retrieved September 16, 2015.

- ↑ Fehrenbach 1968, p. 270.

- ↑ Michael P. Riccards, "Lincoln and the Political Question: The Creation of the State of West Virginia" Presidential Studies Quarterly, Vol. 27, 1997 online edition

- ↑ "The 14th State". Vermont History Explorer. Vermont Historical Society.

- ↑ "Constitution Square Historic Site". Danville/Boyle County Convention and Visitors Bureau.

- 1 2 "Official Name and Status History of the several States and U.S. Territories". TheGreenPapers.com.

- ↑ "Today in History: March 15". loc.gov. Library of Congress.

- ↑ "Today in History: June 20". loc.gov. Library of Congress.

- ↑ "A State of Convenience: The Creation of West Virginia, Chapter Twelve, Reorganized Government of Virginia Approves Separation". Wvculture.org. West Virginia Division of Culture and History.

- ↑ "Virginia v. West Virginia 78 U.S. 39 (1870)". Justia.com.

- ↑ "Political Party Platforms: Libertarian Party Platform of 1972". American Presidency Project. Retrieved September 16, 2015.

- ↑ McFadden, Robert D. (March 5, 1994). "'Home Rule' Factor May Block S.I. Secession". The New York Times. Retrieved October 20, 2009.

- ↑ Bowen, Shannan (September 17, 2008). "Carolina Shores celebrates 10-year split from Calabash". Star-News. Wilmington, North Carolina. Retrieved November 12, 2012.

- ↑ "Kohlhaas v. State (11/17/2006) sp-6072, 147 P3d 714". Touch n Go. Retrieved September 16, 2015.

- ↑ "Should California Be its own Country?". Zócalo Public Square. April 22, 2010. Retrieved September 16, 2015.

- ↑ "Meet the man who wants to make California a sovereign entity". Los Angeles Times. August 26, 2015. Retrieved February 14, 2016.

- ↑ "Political Body: California National Party" (PDF). California Secretary of State. January 8, 2016. Retrieved February 14, 2016.

- ↑ "California could see new political party with independence goal". The Sacramento Bee. January 10, 2016. Retrieved February 14, 2016.

- ↑ "A political searcher agitates for the independent nation of California". Los Angeles Times. January 22, 2016. Retrieved February 14, 2016.

- ↑ Pascaline, Mary (9 November 2016). "What Is Calexit? California Considers Leaving US After Trump Win.". International Business Times. Retrieved 10 November 2016.

- ↑ "A Brief History of the Conch Republic". Conch Republic. Office of the Secretary General. Retrieved November 15, 2012.

- ↑ "Public deserves better than Sager's hypocrisy". Tampa Bay Times. October 27, 2012. Retrieved July 14, 2015.

- ↑ Sager, Jason Patrick (July 4, 2015). "A Conversation About Secession on Independence Day". Retrieved September 16, 2015.

- ↑ McCall, Samuel M. (July 6, 2015). "Pro Confederate Flag Activist Promotes Secession". Florida News Flash. Archived from the original on July 8, 2015. Retrieved July 14, 2015.

- ↑ "2009-2010 Regular Session – SR 632: Jeffersonian Principles; affirming states' rights" (PDF). Georgia General Assembly Legislature. Retrieved September 16, 2015.

- ↑ "HR258". Hawaii State Legislature. Archived from the original on September 28, 2011. Retrieved June 12, 2011.

- ↑ Resolution of legislators in re Heller at the Wayback Machine (archived February 25, 2008)

- ↑ "Platform". New Hampshire Liberty Party. February 9, 2015.

- ↑ Sorens, Jason (July 23, 2001). "Announcement: The Free State Project". The Libertarian Enterprise (131). Retrieved February 9, 2015.

- ↑ Koldin, Michelle (August 28, 1999). "Court over turns conviction of Republic of Texas leader, aide". TimesDaily. Florence, Alabama. Retrieved September 16, 2015.

- ↑ "Welcome to the republic of Texas website!!". Republic of Texas. Retrieved November 12, 2012.

- ↑ "Perry says Texas can leave the union if it wants to". Houston Chronicle. April 15, 2009. Retrieved November 12, 2012.

- ↑ "In Texas, 31% Say State Has Right to Secede From U.S., But 75% Opt To Stay". Rasmussen Reports. April 17, 2009. Retrieved September 16, 2015.

- ↑ "The Treaty of Annexation - Texas; April 12, 1844". Avalon Project. Yale Law School. Retrieved November 12, 2012.

- ↑ "Joint Resolution for Annexing Texas to the United States Approved March 1, 1845". Texas State Library and Archives Commission. August 24, 2011. Retrieved September 16, 2015.

- ↑ "Home". Second Vermont Republic. Retrieved October 4, 2014.

- ↑ Curran, John (June 3, 2007). "In Vermont, nascent secession movement gains traction". The Boston Globe. Retrieved September 16, 2015.

- 1 2 Kauffman, Bill (December 19, 2005). "Free Vermont". The American Conservative. Retrieved September 16, 2015.

- ↑ "Middlebury Declaration". Middlebury Institute. November 7, 2004. Retrieved October 4, 2014.

- ↑ "First North American Secession Convention". Middlebury institute. November 3, 2006. Retrieved November 12, 2012.

- ↑ "Burlington Declaration". Middlebury Institute. November 5, 2006. Retrieved September 16, 2015.

- ↑ Shapiro, Gary (September 27, 2006). "Modern-Day Secessionists Will Hold a Conference on Leaving the Union". The New York Sun. Retrieved September 16, 2015.

- ↑ Philadelphia Inquirer

- ↑ Poovey, Bill (October 3, 2007). "Southern secessionists welcome Yankees". Star-News. Wilmington, North Carolina. Associated Press. Retrieved September 16, 2015.

- ↑ Doyle, Leonard (October 4, 2007). "Anger over Iraq and Bush prompts calls for secession from the US". The Independent. London, UK. Archived from the original on January 17, 2008.

- ↑ Donahue, Bill (June 29, 2008). "Ways and Means". The Washington Post. Retrieved May 23, 2010.

- ↑ "700,000 Americans petition the White House to secede from the US". RT. November 14, 2012. Archived from the original on November 15, 2012. Retrieved November 17, 2012.

- ↑ Ryan, Danielle (November 14, 2012). "White House receives secession pleas from all 50 states". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved November 17, 2012.

- ↑ Woodward, Steve (November 14, 2004). "Welcome to Cascadia". The Oregonian. Retrieved October 4, 2014.

- ↑ Barnett, Galen (September 10, 2008). "Nothing secedes like success". The Oregonian. Retrieved October 4, 2014.

- ↑ Mapes, Jeff (March 23, 2009). "Should we merge Oregon into Washington?". The Oregonian. Retrieved October 4, 2014.

- ↑ Hicks, Bob (May 15, 2009). "Book review: 'The Oregon Companion'". The Oregonian. Retrieved October 4, 2014.

- ↑ Preston, Peter (February 28, 2010). "A world away from Texas". The Guardian. London, UK. Retrieved March 1, 2010.

- ↑ "The Program of the Northwest Front". Northwest Front. Retrieved October 4, 2014.

- ↑ "Official Website". League of the South. Retrieved October 4, 2014.

- ↑ Sebesta, Edward H.; Hague, Euan (2002). "The US Civil War as a Theological War: Confederate Christian Nationalism and the League of the South". Canadian Review of American Studies. University of Toronto Press. 32 (3): 253–284. doi:10.3138/CRAS-s032-03-02.

- ↑ Southern Party of the South West Archives – Asheville Declaration, August 7, 1999 Archived July 17, 2011, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "An Introduction to the Nantucket Reader". Nantucket Reader. Retrieved September 13, 2013.

References

- Amar, Akhil Reed (2005). America's Constitution: A Biography. Random House. ISBN 0-8129-7272-4.

- Buel, Richard Jr. (2005). America on the Brink: How the Political Struggle over the War of 1812 Almost Destroyed the Young Republic. Macmillan. ISBN 1-4039-6238-3.

- Cain, William E., ed. (1995). William Lloyd Garrison and the Fight Against Slavery: Selections from The Liberator. Bedford Books of St. Martin's Press. ISBN 0-312-10386-7.

- Catton, Bruce (1961). The Coming Fury: The Centennial History of the Civil War. Doubleday. pp. 327–28.

- Chernow, Ron (2004). Alexander Hamilton. New York: Penguin Press. p. 586–87. ISBN 978-1-1012-0085-8.

- Eidelberg, Paul (1976). On the Silence of the Declaration of Independence. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press. p. 24. ISBN 0-87023-216-9. Retrieved September 16, 2015.

- Farber, Daniel (2003). Lincoln's Constitution. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-23793-1.

- Fehrenbach, T. R. (1968). Lone Star: A History of Texas and the Texans. p. 270. ISBN 1-57912-537-9.

- Ferling, John (2003). A Leap in the Dark: The Struggle to Create the American Republic. ISBN 978-0-19-515924-0.

- Gienapp, William E. (2002). Abraham Lincoln and Civil War America: A Biography. Oxford University Press. Retrieved September 16, 2015.

- Hickey, Donald R. (1997). "Hartford Convention". In Heidler, David S.; Heidler, Jeanne T. Encyclopedia of the War of 1812. Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-59114-362-4.

- Ketcham, Ralph (1990). James Madison: A Biography. University of Virginia Press. ISBN 0-8139-1265-2.

- Klein, Maury (1997). Days of Defiance: Sumter, Secession, and the Coming of the Civil War. Knopf Doubleday. ISBN 0-679-44747-4.

- Maier, Pauline (1997). American Scripture: Making the Declaration of Independence. Knopf. ISBN 0-679-45492-6.

- Mayer, Henry (1998). All on Fire: William Lloyd Garrison and the Abolition of Slavery. W. W. Norton & Co. ISBN 0-312-18740-8.

- McDonald, Forrest (1985). Novus Ordo Seclorum: The Intellectual Origins of the Constitution. Lawrence, Kansas: University of Kansas Press. pp. 281–82. ISBN 0-70060-311-5.

- McDonald, Forrest. States' Rights and the Union: Imperium in Imperio 1776–1876. (2000) ISBN 0-7006-1040-5

- Meacham, John (2009). "Correspondence of Andrew Jackson". American Lion: Andrew Jackson in the White House. New York: Random House. p. 247.

- Pavković, Aleksandar; Radan, Peter (2007). Creating New States: Theory and Practice of Secession. Ashgate Publishing. p. 222.

- Remini, Robert V. (1984). Andrew Jackson and the Course of American Democracy, 1833–1845. Harper & Row. ISBN 0-06-015279-6.

- Sibley, Joel H. (2005). Storm Over Texas: The Annexation Controversy and the Road to Civil War. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-513944-0.

- Smith, James Morton, ed. (1995). "Chapter 25. The Resolutions Renewed, 1799". The Republic of Letters: The Correspondence between Jefferson and Madison 1776–1826. Vol. 2. New York: W. W. Norton & Co. p. 1119. ISBN 978-0-3930-3691-6.

- Stampp, Kenneth M. (June 1978). "The Concept of a Perpetual Union" (PDF). The Journal of American History. 65 (1): 5–33. doi:10.2307/1888140.

- Stromberg, Joseph R. (1982). "Country Ideology, Republicanism, and Libertarianism: The Thought of John Taylor of Caroline". The Journal of Libertarian Studies. 6 (1): 42. Retrieved September 16, 2015.

- Van Deusen, David (2007) Vermont Secession: The Extreme Right, And Democracy, Catamount Tavern News Service.

- Varon, Elizabeth R. (2008). Disunion: The Coming of the American Civil War, 1789–1859. ISBN 978-0-8078-3232-5.

- "TEXAS V. WHITE". Handbook of Texas Online. Texas State Historical Association. September 19, 2010.

- Wilson, Views of the Constitution

- Wood, Gordon S. (1969). The Creation of the American Republic, 1776–1787. The Norton Library. p. 40. ISBN 0-393-00644-1.

External links

- Declaration of Causes of Seceding States - Ordinances of Secession of Georgia, Mississippi, South Carolina, and Texas