SECAM

SECAM, also written SÉCAM (French pronunciation: [sekam], Séquentiel couleur à mémoire,[1] French for "Sequential colour with memory"), is an analogue color television system first used in France. It was one of three major colour television standards, the others being the European PAL and North American NTSC.

Development of SECAM began in 1956 by a team led by Henri de France working at Compagnie Française de Télévision (later bought by Thomson, now Technicolor). The first SECAM broadcast was made in France in 1967, making it the first such standard to go live in Europe. The system was also selected as the standard for colour in the Soviet Union, who began broadcasts shortly after the French. The standard spread from these two countries to many client states and former colonies.

SECAM remained a major standard into the 2000s. It is in the process of being phased out and replaced by DVB, the new pan-European standard for digital television.

History

Work on SECAM began in 1956. The technology was ready by the end of the 1950s, but this was too soon for a wide introduction. A version of SECAM for the French 819-line television standard was devised and tested, but not introduced. Following a pan-European agreement to introduce color TV only in 625 lines, France had to start the conversion by switching over to a 625-line television standard, which happened at the beginning of the 1960s with the introduction of a second network.

The first proposed system was called SECAM I in 1961, followed by other studies to improve compatibility and image quality.

These improvements were called SECAM II and SECAM III, with the latter being presented at the 1965 CCIR General Assembly in Vienna.

Further improvements were SECAM III A followed by SECAM III B, the adopted system for general use in 1967.

Soviet technicians were involved in the development of the standard, and created their own incompatible variant called NIR or SECAM IV, which was not deployed. The team was working in Moscow's Telecentrum under the direction of Professor Shmakov. The NIR designation comes from the name of the Nautchno-Issledovatelskiy Institut Radio (NIIR, rus. Научно-Исследовательский Институт Радио), a Soviet research institute involved in the studies. Two standards were developed: Non-linear NIR, in which a process analogous to gamma correction is used, and Linear NIR or SECAM IV that omits this process.[2]

SECAM was inaugurated in France on 1 October 1967, on la deuxième chaîne (the second channel), now called France 2. A group of four suited men—a presenter (Georges Gorse, Minister of Information) and three contributors to the system's development—were shown standing in a studio. Following a count from 10, at 2:15 pm the black-and-white image switched to color; the presenter then declared "Et voici la couleur !" (fr: And here is color!)[3] In 1967, CLT of Lebanon became the third television station in the world, after the Soviet Union and France, to broadcast in color utilizing the French SECAM technology.[4]

The first color television sets cost 5000 Francs. Color TV was not very popular initially; only about 1500 people watched the inaugural program in color. A year later, only 200,000 sets had been sold of an expected million. This pattern was similar to the earlier slow build-up of color television popularity in the US.

SECAM was later adopted by former French and Belgian colonies, Greece, the Soviet Union and Eastern bloc countries (except for Romania and Albania), and Middle Eastern countries. However, with the fall of communism, and following a period when multi-standard TV sets became a commodity, many Eastern European countries decided to switch to the German-developed PAL system.

Other countries, notably the United Kingdom and Italy, briefly experimented with SECAM before opting for PAL.

Since late 2000s, SECAM is in the process of being phased out and replaced by DVB.

Development

Some have argued that the primary motivation for the development of SECAM in France was to protect French television equipment manufacturers.[5] However, incompatibility had started with the earlier unusual decision to adopt positive video modulation for French broadcast signals. The earlier systems System A & the 819-line systems were the only other systems to use positive video modulation. In addition, SECAM development predates PAL. NTSC was considered undesirable in Europe because of its tint problem requiring an additional control, which SECAM and PAL solved.[note 1] Nonetheless, SECAM was partly developed for reasons of national pride. Henri de France's personal charisma and ambition may have been a contributing factor. PAL was developed by Telefunken, a German company, and in the post-war De Gaulle era there would have been much political resistance to dropping a French-developed system and adopting a German-developed one instead.

Unlike some other manufacturers, the company where SECAM was invented, Technicolor (known as Thomson until 2010), still sells TV sets worldwide under different brands; this may be due in part to the legacy of SECAM. Thomson bought the company that developed PAL, Telefunken, and today even co-owns the RCA brand —RCA being the creator of NTSC. Thomson also co-authored the ATSC standard which is used for American high-definition television.

The spread of SECAM

The adoption of SECAM in Eastern Europe has been attributed to Cold War political machinations. According to this explanation, East German political authorities were well aware of West German television's popularity and adopted SECAM rather than the PAL encoding used in West Germany. This did not hinder mutual reception in black & white, because the underlying TV standards remained essentially the same in both parts of Germany. However, East Germans responded by buying PAL decoders for their SECAM sets. Eventually, the government in East Berlin stopped paying attention to so-called "Republikflucht via Fernsehen", or "defection via television". Later East German–produced TV sets even included a dual standard PAL/SECAM decoder.

Another explanation for the Eastern European adoption of SECAM, led by the Soviet Union, is that the Russians had extremely long distribution lines between broadcasting stations and transmitters.[6] Long co-axial cables or microwave links can cause amplitude and phase variations, which do not affect SECAM signals.

However, PAL and SECAM are just standards for the color sub carrier, used in conjunction with older standards for the base monochrome signals. The names for these monochrome standards are letters, such as M, B/G, D/K, and L. See CCIR, OIRT and FCC (the standardization bodies).

These signals are much more important to compatibility than the color sub carriers are. They differ by AM or FM sound modulation, signal polarization, relative frequencies within the channel, bandwidth, etc. For example, a PAL D/K TV set will be able to receive a SECAM D/K signal (although in black and white), while it will not be able to decode the sound of a PAL B/G signal. So even before SECAM came to Eastern European countries, most viewers (other than those in East Germany and Yugoslavia) could not have received Western programs. This, along with language issues, meant that in most countries monochrome-only reception did not pose a significant problem for the authorities.

Technical details

Just as with the other color standards adopted for broadcast usage over the world, SECAM is a standard which permits existing monochrome television receivers predating its introduction to continue to be operated as monochrome televisions. Because of this compatibility requirement, color standards added a second signal to the basic monochrome signal, which carries the color information. The color information is called chrominance or C for short, while the black-and-white information is called the luminance or Y for short. Monochrome television receivers only display the luminance, while color receivers process both signals.

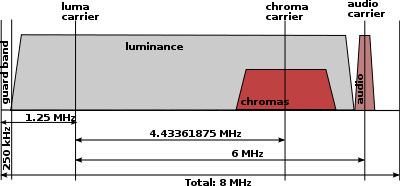

Additionally, for compatibility, it is required to use no more bandwidth than the monochrome signal alone; the color signal has to be somehow inserted into the monochrome signal, without disturbing it. This insertion is possible because the spectrum of the monochrome TV signal is not continuous (for most typical video content), hence empty space exists which can be utilized. This typical lack of continuity results from the discrete nature of the signal, which is divided into frames and lines. (Strictly speaking, monochrome video does use the full spectrum, if arbitrary and unconstrained movement of subjects and/or cameras is permitted. Therefore, all of these color systems compromise luma quality to some extent in exchange for the addition of color—i.e. all of these color signals look worse at some time or other than they would if the color signal were absent.) Analog color systems differ by the way in which infrequently used space in the frequency band of the signal is used. In all cases, the color signal is inserted at the end of the spectrum of the monochrome signal, where it causes less visual distortion (only affecting fine detail) in the uncommon case that the monochrome signal had significant frequency components overlapping the color signal.

In order to be able to separate the color signal from the monochrome one in the receiver, a fixed frequency sub carrier is used, this sub carrier being modulated by the color signal.

The color space is three-dimensional by the nature of the human vision, so after subtracting the luminance, which is carried by the base signal, the color sub carrier still has to carry a two-dimensional signal. Typically the red (R) and the blue (B) information are carried because their signal difference with luminance (R-Y and B-Y) is stronger than that of green (G-Y).

SECAM differs from the other color systems by the way the R-Y and B-Y signals are carried.

First, SECAM uses frequency modulation to encode chrominance information on the sub carrier.

Second, instead of transmitting the red and blue information together, it only sends one of them at a time, and uses the information about the other color from the preceding line. It uses an analog delay line, a memory device, for storing one line of color information. This justifies the "Sequential, With Memory" name.

Because SECAM transmits only one color at a time, it is free of the color artifacts present in NTSC and PAL resulting from the combined transmission of both signals.

This means that the vertical color resolution is halved relative to NTSC. The later PAL system also displays half the vertical resolution of NTSC (i.e., the same as SECAM). Although PAL does not eliminate half of vertical color information during encoding, it combines color information from adjacent lines at the decoding stage, in order to compensate for "color sub carrier phase errors" occurring during the transmission of the Amplitude/Phase-Modulated color sub carrier. This is normally done using a delay line like in SECAM (the result is called PAL D or PAL Delay-Line, sometimes interpreted as DeLuxe), but can be accomplished "visually" in cheap TV sets using PAL-S (PAL simple) decoders. Because the FM modulation of SECAM's color sub carrier is insensitive to phase (or amplitude) errors, phase errors do not cause loss of color saturation in SECAM, although they do in PAL. In NTSC, such errors cause color shifts (hence the "Hue" control on all NTSC TV sets to adjust the color phase with a constant bias).

The color difference signals in SECAM are actually calculated in the YDbDr color space, which is a scaled version of the YUV color space. This encoding is better suited to the transmission of only one signal at a time.

FM modulation of the color information allows SECAM to be completely free of the dot crawl problem commonly encountered with the other analog standards. SECAM transmissions are more robust over longer distances than NTSC or PAL. However, owing to their FM nature, the color signal remains present, although at reduced amplitude, even in monochrome portions of the image, thus being subject to stronger cross color even though color crawl of the PAL type doesn't exist.

Though most of the pattern is removed from PAL and NTSC-encoded signals with a comb filter (designed to segregate the two signals where the luma spectrum may overlap into the spectral space used by the chroma) by modern displays, some can still be left in certain parts of the picture. Such parts are usually sharp edges on the picture, sudden color or brightness changes along the picture or certain repeating patterns, such as a checker board on clothing. Dot crawl patterns can be completely removed by connecting the display to the signal source through a cable or signal format different from composite video (yellow RCA cable) or a coaxial cable, such as S-Video, which carries the chroma signal in a separate band all its own, leaving the luma to use its entire band, including the usually empty parts when they are needed. FM SECAM is a continuous spectrum, so unlike PAL and NTSC even a perfect digital comb filter could not entirely separate SECAM Colour and Luminance.

The idea of reducing the vertical color resolution comes from Henri de France, who observed that color information is approximately identical for two successive lines. Because the color information was designed to be a cheap, backwards compatible addition to the monochrome signal, the color signal has a lower bandwidth than the luminance signal, and hence lower horizontal resolution. Fortunately, the human visual system is similar in design: it perceives changes in luminance at a higher resolution than changes in chrominance, so this asymmetry has minimal visual impact. It was therefore also logical to reduce the vertical color resolution.

A similar paradox applies to the vertical resolution in television in general: reducing the bandwidth of the video signal will preserve the vertical resolution, even if the image loses sharpness and is smudged in the horizontal direction. Hence, video could be sharper vertically than horizontally. Additionally, transmitting an image with too much vertical detail will cause annoying flicker on television screens, as small details will only appear on a single line (in one of the two interlaced fields), and hence be refreshed at half the frequency. (This is a consequence of interlaced scanning that is obviated by progressive scan.) Computer-generated text and inserts have to be carefully low-pass filtered to prevent this.

The latest European efforts towards an analog standard, resulting in MAC systems, still used the sequential colour transmission idea of SECAM, with only one of time-compressed U and V components being transmitted on a given line. The D2-MAC standard enjoyed some short real market deployment, particularly in northern European countries. To some extent, this idea is still present in 4:2:0 digital sampling format, which is used by most digital video medias available to the public. In this case, however, colour resolution is halved in both horizontal and vertical directions thus yielding a more symmetrical behavior.

SECAM varieties

L, B/G, D/K, H, K, M (broadcast)

There are six varieties of SECAM:

- French SECAM (SECAM-L)

- French SECAM (SECAM-L) is used only in France, Luxembourg (only RTL9 on CH 21 from Dudelange) and Tele Monte-Carlo Transmitters in the south of France.

- SECAM-B/G

- SECAM-B/G is/was used in parts of the Middle East, former East Germany and Greece

- SECAM-D/K

- SECAM-D/K is used in the Commonwealth of Independent States and parts of Eastern Europe (this is simply SECAM used with the D and K monochrome TV transmission standards) although most Eastern European countries have now migrated to other systems.

- SECAM-H

- Around 1983–1984 a new color identification standard ("Line SECAM or SECAM-H") was introduced in order to make more space available inside the signal for adding teletext information (originally according to the Antiope standard). Identification bursts were made per-line (like in PAL) rather than per-picture. Very old SECAM TV sets might not be able to display color for today's broadcasts, although sets manufactured after the mid-1970s should be able to receive either variant.

- SECAM-K

- France also introduced the SECAM standard to its dependencies. However, the SECAM standard used in France's overseas possessions (as well as African countries that were once ruled by France) was slightly different from the SECAM used in Metropolitan France. The SECAM standard used in Metropolitan France used the SECAM-L and a variant of the channel information for VHF channels 2-10. French overseas possessions and many French-speaking African countries use the SECAM-K1 standard and a mutually incompatible variant of the channel information for VHF channels 4-9 (not channels 2-10).

- SECAM-M

- Around 1970–1991, SECAM-M was used in Cambodia and Vietnam (Hanoi and cities North).

MESECAM (home recording)

MESECAM is a method of recording SECAM color signals onto VHS or Betamax video tape. It should not be mistaken for a broadcast standard.

"Native" SECAM recording was originally devised for machines sold for the French market. At a later stage, countries where both PAL and SECAM signals were available (notably the Middle East, hence the Acronym "Middle East SECAM"), developed a cheap method of converting PAL video machines to record SECAM signals also using the PAL circuitry. A tape produced by this method is not compatible with "native" SECAM tapes as produced by VCRs in the French market. It will play in black and white only, the color is lost. So the world is left with two different incompatible standards for recording SECAM on video cassette.

Although being a workaround, MESECAM is much more widespread than "native" SECAM. It has been the only method of recording SECAM signals to VHS in almost all countries that ever used SECAM, including as mentioned the Middle East and all countries in Eastern Europe. "Native" SECAM recording (marketing term: "SECAM-West") is only used in France and adjacent countries. Most VHS machines advertised as "SECAM capable" outside France can be expected to be of the MESECAM variety only.

Technical details

On VHS tapes, the luminance signal is recorded in its original form (albeit with some reduction of bandwidth) but the PAL or NTSC chrominance signal is too sensitive to small changes in frequency caused by inevitable small variations in tape speed to be recorded directly. Instead, it is first down converted to the lower frequency of 630 kHz, and the complex nature of the PAL or NTSC sub carrier means that the down conversion must be done via heterodyning to ensure that information is not lost.

The SECAM sub carriers on the other hand, consisting of two simple FM signals at 4.41 MHz and 4.25 MHz, do not need such complex processing. The VHS specification for "native" SECAM recording requires that they be divided by 4 on recording to give sub carriers of approximately 1.1 MHz and 1.06 MHz, and multiplied by 4 again on playback. A true dual-standard PAL and SECAM video recorder therefore requires two color processing circuits, adding to complexity and expense. Since some countries in the Middle East use PAL and others use SECAM, the region has adopted a shortcut, and uses the PAL mixer-down converter approach for both PAL and SECAM. This works well and simplifies VCR design.

It is interesting to note that it is often possible to record SECAM video on an unmodified PAL VCR, thus creating MESECAM tapes, which can be played back in color through another PAL VCR into a SECAM TV. Basic PAL VCRs work better for this, ones that are more sophisticated detect the SECAM signal as "not-PAL" and refuse to record it in color.

Many PAL VHS recorders, with MESECAM, have had their analog tuner modified in French-speaking western Switzerland (Switzerland used the PAL-B/G analog broadcast standard while the bordering France used SECAM-L; nowadays both countries have switched their broadcasting to digital-only). The original tuner in those PAL recorders allows only PAL-B/G reception. The Swiss importers added a little circuit, with a specific IC, for the French SECAM-L standard; the tuner thus became multistandard, but the VCR recorded French broadcasts, in MESECAM. Such tapes are played in black and white on "native" SECAM VCRs, and native SECAM tapes are also played in B/W in these modified tuner VCRs. A specific stamp was added on the machines saying "PAL+SECAM".

However some special VHS video recorders are available which can allow viewers the flexibility of enjoying PAL-M recordings using a standard PAL (625/50 Hz) colour TV, or even through multi-system TV sets.Video recorders like Panasonic NV-W1E (AG-W1 for the USA), AG-W2, AG-W3, NV-J700AM, Aiwa HV-MX100, HV-MX1U, Samsung SV-4000W and SV-7000W feature a digital TV system conversion circuitry.

Disadvantages

Unlike PAL or NTSC, analog SECAM programming cannot easily be edited in its native analog form. Because it uses frequency modulation, SECAM is not linear with respect to the input image (this is also what protects it against signal distortion), so electrically mixing two (synchronized) SECAM signals does not yield a valid SECAM signal, unlike with analog PAL or NTSC. For this reason, to mix two SECAM signals, they must be demodulated, the demodulated signals mixed, and are remodulated again. Hence, post-production is often done in PAL, or in component formats, with the result encoded or transcoded into SECAM at the point of transmission. Reducing the costs of running television stations is one reason for some countries' recent switchovers to PAL.

Most TVs currently sold in SECAM countries support both SECAM and PAL, and more recently composite video NTSC as well (though not usually broadcast NTSC, that is, they cannot accept a broadcast signal from an antenna). Although the older analog camcorders (VHS, VHS-C) were produced in SECAM versions, none of the 8 mm or Hi-band models (S-VHS, S-VHS-C, and Hi-8) recorded it directly. Camcorders and VCRs of these standards sold in SECAM countries are internally PAL. They use an internal SECAM to PAL converter for recording of broadcast TV transmitted in SECAM. The result could be converted back to SECAM in some models; most people buying such expensive equipment would have a multistandard TV set and as such would not need a conversion. Digital camcorders or DVD players (with the exception of some early models) do not accept or output a SECAM analog signal. However, this is of dwindling importance: since 1980 most European domestic video equipment uses French-originated SCART connectors, allowing the transmission of RGB signals between devices. This eliminates the legacy of PAL, SECAM, and NTSC color sub carrier standards.

In general, modern professional equipment is now all-digital, and uses component-based digital interconnects such as CCIR 601 to eliminate the need for any analog processing prior to the final modulation of the analog signal for broadcast. However, large installed bases of analog professional equipment still exist, particularly in third world countries. In most cases all processing within the TV-station is PAL and on the output line a PAL to SECAM transcoder is used before feeding the transmitter. This is because switchers and effect mixers can easily handle PAL (or NTSC) but the SECAM signal can't be mixed in the same way due to the frequency modulation of the color information.

Countries and territories that use SECAM

This is a list of nations that currently authorize the use of the SECAM standard for television broadcasting. Nations that have moved to PAL or DVB-T are listed separately.

| SECAM users | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Migration from SECAM to PAL

Europe

|

Africa

Asia

America

The Slovakia, Hungary and the Baltic countries also changed their underlying sound carrier standard from D/K to B/G which is used in most of Western Europe, to facilitate use of imported broadcast equipment. This required viewers to purchase multistandard receivers though. The other countries mentioned kept their existing standards (B/G in the cases of East Germany and Greece, D/K for the rest).[10] Migration from SECAM to DVB-T

See alsoNotes

References

External links

|