Brideshead Revisited

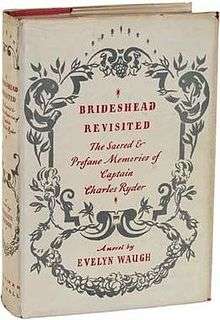

Brideshead Revisited, 1945 first UK edition | |

| Author | Evelyn Waugh |

|---|---|

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Publisher | Chapman and Hall |

Publication date | 1945 |

| Pages | 402 |

| Preceded by | Put Out More Flags (1942) |

| Followed by | Scott-King's Modern Europe (1947) |

Brideshead Revisited, The Sacred & Profane Memories of Captain Charles Ryder is a novel by English writer Evelyn Waugh, first published in 1945. It follows, from the 1920s to the early 1940s, the life and romances of the protagonist Charles Ryder, including his friendship with the Flytes, a family of wealthy English Catholics who live in a palatial mansion called Brideshead Castle. Ryder has relationships with two of the Flytes: Sebastian and Julia. The novel explores themes including nostalgia for the age of English aristocracy, Catholicism, and the nearly overt homosexuality of Sebastian Flyte's coterie at Oxford University. A faithful and well-received television adaptation of the novel was produced in an 11-part miniseries by Granada Television in 1981.

Plot

In 1923, protagonist and narrator Charles Ryder, an undergraduate studying history at a college very like Hertford College, Oxford, is befriended by Lord Sebastian Flyte, the younger son of the aristocratic Lord Marchmain and an undergraduate at Christ Church. Sebastian introduces Charles to his eccentric and aesthetic friends, including the haughty and homosexual Anthony Blanche. Sebastian also takes Charles to his family's palatial mansion, Brideshead Castle, in Wiltshire[1] where Charles later meets the rest of Sebastian's family, including his sister Julia.

During the long summer holiday Charles returns home to London, where he lives with his widowed father, Edward Ryder. The conversations there between Charles and Edward provide some of the best-known comic scenes in the novel. Charles is called back to Brideshead after Sebastian incurs a minor injury, and Sebastian and Charles spend the remainder of the holiday together.

Sebastian's family are Roman Catholic, which influences the Flytes' lives as well as the content of their conversations, all of which surprises Charles, who had always assumed Christianity was "without substance or merit". Lord Marchmain had converted from Anglicanism to Roman Catholicism to marry his wife, but he later abandoned both his marriage and his new religion, and moved to Venice, Italy. Left alone, Lady Marchmain focuses even more on her faith, which is also enthusiastically espoused by her eldest son, Lord Brideshead ("Bridey"), and by her youngest daughter, Cordelia.

Sebastian, a troubled young man, descends into alcoholism, drifting away from the family over a two-year period. He flees to Morocco, where his drinking ruins his health. He eventually finds some solace as an under-porter and object of charity at a Catholic monastery in Tunisia.

Sebastian's drifting leads to Charles's own estrangement from the Flytes. Charles marries and fathers two children, but he becomes cold towards his wife, and she is unfaithful to him. He eventually forms a relationship with Sebastian's younger sister Julia. Julia has married but separated from the rich but unsophisticated Canadian–born businessman and politician Rex Mottram. This marriage caused great sorrow to her mother, because Rex, though initially planning to convert to Roman Catholicism, turns out to have divorced a previous wife in Canada, so he and Julia ended up marrying without fanfare in an Anglican church that accepts divorced people.

Charles and Julia plan to divorce their respective spouses so that they can marry each other. On the eve of the Second World War, the ageing Lord Marchmain, terminally ill, returns to Brideshead to die in his ancestral home. Appalled by the marriage of his eldest son Brideshead to a middle-class widow past childbearing age, he names Julia heir to the estate, which prospectively offers Charles marital ownership of the house. However, Lord Marchmain's return to the faith on his deathbed changes the situation: Julia decides she cannot enter a sinful marriage with Charles, who has also been moved by Lord Marchmain's reception of the sacraments.

The plot concludes in the early spring of 1943 (or possibly 1944 – the date is disputed).[2] Charles is "homeless, childless, middle-aged and loveless". He has become an army officer, after establishing a career as an architectural artist, and finds himself unexpectedly billeted at Brideshead, which has been taken into military use. He finds the house damaged by the army, but the private chapel, closed after Lady Marchmain's death in 1926, has been reopened for the soldiers' worship. It occurs to him that the efforts of the builders – and, by extension, God's efforts – were not in vain, although their purposes may have appeared, for a time, to have been frustrated.[3]

Motifs

Catholicism

Catholicism is a significant theme of the book. Evelyn Waugh was a convert to Catholicism and Brideshead depicts the Roman Catholic faith in a secular literary form. Waugh wrote to his literary agent A. D. Peters, that "I hope the last conversation with Cordelia gives the theological clue. The whole thing is steeped in theology, but I begin to agree that the theologians won't recognise it."

The book brings the reader, through the narration of the initially agnostic Charles Ryder, in contact with the severely flawed but deeply Catholic Flyte family. The Catholic themes of divine grace and reconciliation are pervasive in the book. Most of the major characters undergo a conversion in some way or another. Lord Marchmain, a convert from Anglicanism to Catholicism, who lived as an adulterer, is reconciled with the Church on his deathbed. Julia, who entered a marriage with Rex Mottram that is invalid in the eyes of the Catholic Church, and is involved in an extramarital affair with Charles. Julia realizes that marrying Charles will separate her forever from her faith and decides to leave him, in spite of her great attachment to him. Sebastian, the charming and flamboyant alcoholic, ends up in service to a monastery while struggling against his alcoholism.

Most significant is Charles's apparent conversion, which is expressed subtly at the end of the book, set more than 20 years after his first meeting Sebastian. Charles kneels down in front of the tabernacle of the Brideshead chapel and says a prayer, "an ancient, newly learned form of words" – implying recent instruction in the catechism. Waugh speaks of his belief in grace in a letter to Lady Mary Lygon: "I believe that everyone in his (or her) life has the moment when he is open to Divine Grace. It's there, of course, for the asking all the time, but human lives are so planned that usually there's a particular time – sometimes, like Hubert, on his deathbed – when all resistance is down and grace can come flooding in."[4]

Waugh quotes from a short story by G. K. Chesterton to illustrate the nature of grace. Cordelia, in conversation with Charles Ryder, quotes a passage from the Father Brown detective story "The Queer Feet": "I caught him, with an unseen hook and an invisible line which is long enough to let him wander to the ends of the world, and still to bring him back with a twitch upon the thread."[5] This quotation provides the foundation for Waugh's Roman Catholic treatment of the interplay of free will and grace in the moment of conversion.

The same themes were criticised by Waugh's contemporaries. Novelist Henry Green, wrote to Waugh: "The end was not for me. As you can imagine my heart was in my mouth all through the deathbed scene, hoping against hope that the old man would not give way, that is, take the course he eventually did." And Edmund Wilson, who had praised Waugh as the hope of the English novel, wrote "The last scenes are extravagantly absurd, with an absurdity that would be worthy of Waugh at his best if it were not – painful to say – meant quite seriously."

Nostalgia for an age of English nobility

The Flyte family is widely found to symbolise the English nobility. One reads in the book that Brideshead has "the atmosphere of a better age", and (referring to the deaths of Lady Marchmain's brothers in the Great War) "these men must die to make a world for Hooper ... so that things might be safe for the travelling salesman, with his polygonal pince-nez, his fat, wet handshake, his grinning dentures".

According to Martin Amis, the book "squarely identifies egalitarianism as its foe and proceeds to rubbish it accordingly".[6]

Charles and Sebastian's relationship

The question of whether the relationship between Charles and Sebastian is homosexual or platonic has been debated, particularly in an extended exchange between David Bittner and John Osborne in the Evelyn Waugh Newsletter and Studies from 1987 to 1991.[7] In 1994 Paul Buccio argued that the relationship was in the Victorian tradition of "intimate male friendships", which includes "Pip and Herbert Pocket [from Charles Dickens' Great Expectations], ... Sherlock Holmes and Doctor Watson, Ratty and Mole (The Wind in the Willows)".[8] David Higdon argued that "[I]t is impossible to regard Sebastian as other than gay; [and] Charles is so homoerotic he must at least be cheerful"; and that the attempt of some critics to downplay the homoerotic dimension of Brideshead is part of "a much larger and more important sexual war being fought as entrenched heterosexuality strives to maintain its hegemony over important twentieth century works".[7] In 2008 Christopher Hitchens derided "the ridiculous word 'platonic' that for some peculiar reason still crops up in discussion of the story".[9]

Those who interpret the relationship as overtly homosexual note that the novel states that Charles had been "in search of love in those days" when he first met Sebastian, and quote his finding "that low door in the wall [...] which opened on an enclosed and enchanted garden" (an allusion to Alice's Adventures in Wonderland by Lewis Carroll). The phrase "our naughtiness [was] high on the catalogue of grave sins" is also seen as a suggestion that their relationship is homosexual, because this is a mortal sin in Roman Catholic dogma.[7] Attention has also been drawn to the fact that Charles impatiently awaits Sebastian's letters, and the suggestion in the novel that one of the reasons Charles is later in love with Julia is her physical similarity to Sebastian.[7]

Waugh wrote in 1947 that "Charles's romantic affection for Sebastian is part due to the glitter of the new world Sebastian represents, part to the protective feeling of a strong towards a weak character, and part a foreshadowing of the love for Julia which is to be the consuming passion of his mature years."[10] In the novel, Cara, Lord Marchmain's mistress, says to Charles that his romantic relationship with Sebastian forms part of a process of emotional development typical of "the English and the Germans". This passage is quoted at the beginning of Paul M. Buccio's essay on the Victorian and Edwardian tradition of romantic male friendships.[8]

Principal characters

- Charles Ryder – The protagonist and narrator of the story was raised primarily by his father after his mother died. Charles's family background is financially comfortable but emotionally hollow. He is unsure about his desires or goals in life, and is dazzled by the charming, flamboyant and seemingly carefree young Lord Sebastian Flyte. Charles, though dissatisfied with what life seems to offer, has modest success both as a student and later as a painter; less so as an Army officer. His path repeatedly crosses those of various members of the Marchmain family, and each time they awaken something deep within him. It has been noted that Charles Ryder bears some resemblance to artist Felix Kelly (1914–1994), who painted murals for aristocratic country houses.[11] Kelly was commissioned to paint murals for Castle Howard, which was used as a location in the television series and is where Ryder is depicted painting a mural for the Garden Room.[12]

- Edward "Ned" Ryder – Charles's father is a somewhat distant and eccentric figure, but possessed of a keen wit. He seems determined to teach Charles to stand on his own feet. When Charles is forced to spend his holidays with him because he has already spent his allowance for the term, Ned, in what are considered some of the funniest passages in the book, strives to make Charles as uncomfortable as possible, indirectly teaching him to mind his finances more carefully.

- Lord Marchmain (Alexander Flyte, The Marquess of Marchmain) – As a young man, Lord Marchmain fell in love with a Roman Catholic woman and converted to marry her. The marriage was unhappy and, after the First World War, he refused to return to England, settling in Venice with his Italian mistress, Cara.

- Lady Marchmain (Teresa Flyte, The Marchioness of Marchmain) – A member of an ancient Roman Catholic family (the people that Waugh himself most admired). She brought up her children as Roman Catholics against her husband's wishes. Abandoned by her husband, Lady Marchmain rules over her household, enforcing her Roman Catholic morality on her children.

- "Bridey" (Earl of Brideshead) – The elder son of Lord and Lady Marchmain who, as the Marquess's heir, holds the courtesy title "Earl of Brideshead". He follows his mother's strict Roman Catholic beliefs, and once aspired to the priesthood. However, he is unable to connect in an emotional way with most people, who find him cold and distant. His actual Christian name is not revealed.

- Lord Sebastian Flyte – The younger son of Lord and Lady Marchmain is haunted by a profound unhappiness brought on by a troubled relationship with his mother. An otherwise charming and attractive companion, he numbs himself with alcohol. He forms a deep friendship with Charles. Over time, however, the numbness brought on by alcohol becomes his main desire. He is thought to be based on Alastair Graham (whose name was mistakenly substituted for Sebastian's several times in the original manuscript), Hugh Patrick Lygon and Stephen Tennant.[13] Also, his relationship with his teddy bear, Aloysius, was inspired by John Betjeman and his teddy bear Archibald Ormsby-Gore.[14]

- Lady Julia Flyte – The elder daughter of Lord and Lady Marchmain, who comes out as a debutante in the beginning of the story, eventually marrying Rex Mottram. Charles loves her for much of their lives, due in part to her resemblance to her brother Sebastian. Julia refuses at first to be controlled by the conventions of Roman Catholicism, but turns to it later in life.

- Lady Cordelia Flyte – The youngest of the siblings is the most devout and least conflicted in her beliefs. She aspires solely to serve God.

- Anthony Blanche – A friend of Charles and Sebastian's from Oxford, and an overt homosexual. His background is unclear but there are hints that he may be of Italian or Spanish extraction. Of all the characters, Anthony has the keenest insight into the self-deception of the people around him. Although he is witty, amiable and always an interesting companion, he manages to make Charles uncomfortable with his stark honesty, flamboyance and flirtatiousness. The character is based on Brian Howard, a contemporary of Waugh at Oxford and flamboyant homosexual. When Sebastian and Charles return to Oxford, in the Michaelmas term of 1923, they learn that Anthony Blanche has been sent down.[15]

- Viscount "Boy" Mulcaster – An acquaintance of Charles from Oxford. Brash, bumbling and thoughtless, he personifies the privileged hauteur of the British aristocracy. He later proves an engaging and fondly doting uncle to "John-john" Ryder. As with Lord Brideshead, his Christian name is never revealed.

- Celia Ryder – Charles's wife, "Boy" Mulcaster's sister, and Julia's former schoolmate; a vivacious and socially active beauty. Charles marries her largely for convenience, which is revealed by Celia's infidelities. Charles feels freed by Celia's betrayal and decides to pursue love elsewhere, outside of their marriage.

- Rex Mottram – A Canadian of great ambition, said to be based on Max Aitken, Lord Beaverbrook, a Canadian, and Brendan Bracken. Mottram wins a seat in the House of Commons. Through his marriage to Julia, he connects to the Marchmains as another step on the ladder to the top. He is disappointed with the results, and he and Julia agree to lead separate lives.

- "Sammy" Samgrass – A Fellow of All Souls College, Oxford, and Lady Marchmain's "pet don." Lady Marchmain funds Samgrass's projects and flatters his academic ego, while asking him to keep Sebastian in line and save him from expulsion. Samgrass uses his connections with the aristocracy to further his personal ambitions.

- Cara – Lord Marchmain's Italian mistress. She is very protective of Lord Marchmain and is forthright and insightful in her relationship with Charles.

- "Nanny" Hawkins – Beloved nanny to the four Flyte children, who lives in retirement at Brideshead.

Minor characters

- Jasper – Charles's cousin, who gives him advice about student life at Oxford, which Charles ignores.

- Kurt – Sebastian's German friend. A deeply inadequate ex-soldier with a permanently septic foot (due to a self-inflicted gunshot wound) whom Sebastian meets in Tunisia, a man so inept that he needs Sebastian to look after him.

- Mrs (Beryl) Muspratt – The widow of an admiral, she meets and marries a smitten Brideshead, but never becomes mistress of the great house.

Waugh's statements about the novel

Waugh wrote that the novel "deals with what is theologically termed 'the operation of Grace', that is to say, the unmerited and unilateral act of love by which God continually calls souls to Himself".[16] This is achieved by an examination of the Roman Catholic aristocratic Flyte family as seen by the narrator, Charles Ryder.

In various letters, Waugh himself refers to the novel a number of times as his magnum opus; however, in 1950 he wrote to Graham Greene stating "I re-read Brideshead Revisited and was appalled." In Waugh's preface to his revised edition of Brideshead (1959) the author explained the circumstances in which the novel was written, following a minor parachute accident in the six months between December 1943 and June 1944. He was mildly disparaging of the novel, stating; "It was a bleak period of present privation and threatening disaster – the period of soya beans and Basic English – and in consequence the book is infused with a kind of gluttony, for food and wine, for the splendours of the recent past, and for rhetorical and ornamental language which now, with a full stomach, I find distasteful."

Acclaim

In the United States, Brideshead Revisited was the Book of the Month Club selection for January 1946.[17] In 1998, the Modern Library ranked Brideshead Revisited No. 80 on its list of the 100 best English-language novels of the 20th century. In 2003, the novel was listed at number 45 on the BBC survey The Big Read.[18] In 2005, it was chosen by Time magazine as one of the one hundred best English-language novels from 1923 to the present.[19] In 2009, Newsweek magazine listed it as one of the 100 best books of world literature.[20]

Adaptations

In 1981 Brideshead Revisited was adapted as an 11-episode TV serial, produced by Granada Television and aired on ITV, starring Jeremy Irons as Charles Ryder and Anthony Andrews as Lord Sebastian Flyte. The bulk of the serial was directed by Charles Sturridge, with a few sequences filmed by Michael Lindsay-Hogg. John Mortimer was given a credit as writer, but most of the scripts were based on work by producer Derek Granger.

To mark the 70th anniversary of its publication in 2003, BBC Radio 4 Extra produced a four-part adaptation, with Ben Miles as Charles Ryder and Jamie Bamber as Lord Sebastian Flyte. This version was adapted for radio by Jeremy Front and directed by Marion Nancarrow.[21][22]

In 2008 BBC Audiobooks released an unabridged reading of the book by Jeremy Irons. The recording is 11.5 hours long and consists of 10 CDs.[23]

In 2008 Brideshead Revisited was developed into a feature film of the same title, with Emma Thompson as Lady Marchmain, Matthew Goode as Charles Ryder, and Ben Whishaw as Lord Sebastian Flyte. The movie was directed by Julian Jarrold and adapted by Jeremy Brock and Andrew Davies.

References in other media

- In scene 2 of Tom Stoppard's play Arcadia (1993), one character refers to another character who attends Oxford as "Brideshead Regurgitated." Et in Arcadia ego, the Latin phrase which is the title of the major section (Book One) of Brideshead Revisited, is also a central theme to Tom Stoppard's play. Stoppard's phrase may have been inspired by the 1980s BBC comedy series Three of a Kind, starring Tracey Ullman, Lenny Henry and David Copperfield, which featured a recurring sketch entitled "Brideshead Regurgitated", with Henry in the role of Charles Ryder.

- In the early 1980s, following the release of the television series, the Australian Broadcasting Commission (from 1983, Australian Broadcasting Corporation) produced a radio show called Brunswick Heads Revisited. Brunswick Heads is a coastal town in northern New South Wales. The series was a spoof, and made fun of the 'Englishness' of Brideshead and many amusing parallels could be drawn between the upper class characters from Brideshead and their opposite numbers from rural Australia.

- Paula Byrne's biography of Evelyn Waugh, titled Mad World: Evelyn Waugh and the Secrets of Brideshead, was published by HarperPress in the UK in August 2009 and HarperCollins New York in the US in April 2010. An excerpt was published in the Sunday Times 9 August 2009 under the headline "Sex Scandal Behind 'Brideshead Revisited'". The book concerns the 7th Earl of Beauchamp, who was the father of Waugh's friend Hugh Lygon. It states that the exiled Lord Marchmain is a version of Lord Beauchamp and Lady Marchmain of Lady Beauchamp, that the dissolute Lord Sebastian Flyte was modelled after Hugh Lygon and Lady Julia Flyte after Lady Mary Lygon. The book, which Byrne describes in the preface as a "partial life," identifies other real-life bases for events and characters in Waugh's novel, though Byrne argues carefully against simple one-to-one correspondences, suggesting instead that Waugh combined people, places and events into composite inventions, subtle transmutations of life into fiction. An illustrated extract appeared in the April 2010 issue of Vanity Fair in advance of American publication.

Related works

- Marchmain House, the "supposedly luxurious" block of flats that replaced the Flytes' town house, serves as the wartime base for HOO (Hazardous Offensive Operations) Headquarters in Waugh's later novel Officers and Gentlemen (1955).

- A fragment about the young Charles Ryder, entitled "Charles Ryder's Schooldays", was found after Waugh's death and is available in collections of Waugh's short works

Notes

- ↑ "100 Local-Interest Writers And Works". South Central MediaScene. Retrieved 13 December 2012.

- ↑ David Cliffe (2002). "The Brideshead Revisited Companion". p. 11. Retrieved 13 December 2012.

- ↑ Giles Foden (22 May 2004). "Waugh versus Hollywood". The Guardian. Retrieved 13 December 2012.

Evelyn Waugh's disdain for the cinema is revealed in memos he sent to the 'Californian savages' during negotiations over film versions of Brideshead Revisited and Scoop. Giles Foden decodes two unconventional treatments

- ↑ Amory, Mark (ed), The Letters of Evelyn Waugh. Ticknor & Fields, 1980. p. 520.

- ↑ Chesterton, G. K., The Collected Works of G. K. Chesterton, story "The Queer Feet", Ignatius Press, 2005: p. 84.

- ↑ Amis (2001)

- 1 2 3 4 Highdon, David Leon. "Gay Sebastian and Cheerful Charles: Homoeroticism in Waugh's Brideshead Revisited". ARIEL: A Review of International English Literature. (2) 5:4, October 1994.

- 1 2 Buccio, Paul M. "At the Heart of Tom Brown's Schooldays: Thomas Arnold and Christian Friendship". Modern Language Studies. Vol. 25, No. 4 (Autumn, 1995), pp. 57–74.

- ↑ Hitchens, Christopher. "'It's all on account of the war'". The Guardian. 26 September 2008.

- ↑ Waugh, Evelyn. "Brideshead Revisited" (memorandum). 18 February 1947. Reprinted in: Foden, Giles. "Waugh versus Hollywood". The Guardian. 21 May 2004.

- ↑ Trevelyan, Jill (28 March 2009), "Brideshead revisited", NZ Listener, archived from the original on 3 June 2009.

- ↑ Donald Bassett, "Felix Kelly and Brideshead" in the British Art Journal, Vol. 6, No. 2 (Autumn 2005): 52–7. Also, Donald Bassett, Fix: The Art & Life of Felix Kelly, 2007.

- ↑ Copping, Jasper (18 May 2008). "Brideshead Revisited: Where Evelyn Waugh found inspiration for Sebastian Flyte". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 22 August 2011.

- ↑ "Aloysius, The Brideshead Bear". Retrieved 1 September 2011.

- ↑ Frank Kermode. "Introduction". Brideshead Revisited. Everyman's Library. p. xvii. ISBN 978-1-85715-172-5.

- ↑ Memo dated 18 February 1947 from Evelyn Waugh to Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, reproduced in Giles Foden (22 May 2004). "Waugh versus Hollywood". The Guardian. p. 34.

- ↑ Jeffrey M. Heath, The Picturesque Prison: Evelyn Waugh and his writing (1982), p. 186

- ↑ "BBC – The Big Read". BBC. April 2003, Retrieved 19 October 2012

- ↑ Richard Lacayo (16 October 2005). "All-TIME 100 Novels. The critics Lev Grossman and Richard Lacayo pick the 100 best English-language novels published since 1923—the beginning of TIME.". Time.com.

- ↑ "Newsweek's Top 100 Books: The Meta-List – Book awards". Library Thing.

- ↑ Waugh, Evelyn. Brideshead Revisited. BBC Radio 4 Extra.

- ↑ Brideshead Revisited

- ↑ Audible.co.uk: Brideshead Revisited

References

- Waugh, Evelyn (1973) [1946]. Brideshead Revisited. Boston: Little, Brown and Company. ISBN 0-316-92634-5.

- Amis, Martin (2001). The War Against Cliché. New York: Hyperion. ISBN 0-7868-6674-8.

Further reading

- Mulvagh, Jane (2008) "Madresfield: The Real Brideshead". London, Doubleday.ISBN 978-0-385-60772-8

- Byrne, Paula (2009). Mad World: Evelyn Waugh and the Secrets of Brideshead. London: Harper Press. ISBN 978-0-00-724376-1

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Brideshead Revisited |

- 1945 NYtimes.com, New York Times Book Review on Brideshead Revisited

- A Companion to the novel with exhaustive footnotes on cultural references in the text

- Downloadable audio about Brideshead Revisited and Evelyn Waugh from EWTN

- Guardian.co.uk, Article Regarding Waugh and Hollywood.

- May 2008 Telegraph.co.uk, Telegraph Magazine, edited extract from 'Madresfield: The Real Brideshead' by Jane Mulvagh (Doubleday)