Sea mink

| Sea mink Temporal range: Holocene | |

|---|---|

| |

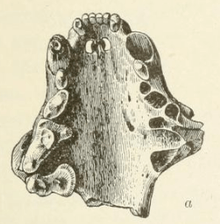

| Palatal aspect of skull | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Carnivora |

| Family: | Mustelidae |

| Subfamily: | Mustelinae |

| Genus: | Neovison |

| Species: | †N. macrodon |

| Binomial name | |

| †Neovison macrodon (Prentis, 1903) | |

| |

| The sea mink was found in the Gulf of Maine area. | |

| Synonyms[2][3] | |

The sea mink (Neovison macrodon) is an extinct species of carnivore from the eastern coast of North America in the family Mustelidae, the largest family in the order Carnivora. It was most closely related to the American mink (Neovison vison), however it is debated whether or not the sea mink was a subspecies of the American mink (making it Neovison vison macrodon) or a species of its own. Distinctions made between the two minks is that the sea mink was larger and had redder fur. In fact, the justification for it being its own species is the size difference between it and the American mink. However, the sea mink was first described in 1903 after its extinction, so information regarding its external appearances and behaviors all stem from speculation and accounts made by fur traders and Native Americans. It was found on the New England coast and the Maritime Provinces, though its range may have stretched further south during the last glacial period. Conversely, its range may have been restricted to solely the New England coast, specifically the Gulf of Maine, or just islands off of it. As it was the largest of the minks, the sea mink was more desirable to fur traders than other mink species, and became extinct sometime in the late 1800s.

Taxonomy and etymology

| New World weasels | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Relations of the sea mink within Mustela[4] |

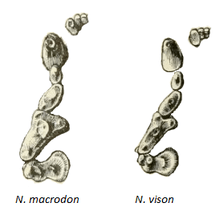

Debate has occurred regarding whether the sea mink was its own species, or a subspecies of the American mink. Those who argue that the sea mink was a subspecies often refer to it as Neovison vison macrodon.[5] The sea mink was first described as Lutreola macrodon, distinct from the American mink, by Daniel Webster Prentis in 1903 after it became extinct. The skull fragments used to first describe it were recovered from Native American shell middens in New England like most remains of the sea mink, however a complete specimen does not exist.[6] Most remains are skull fragments as well.[7] A study in 1911 by Frederic Brewster Loomis, an American paleontologist, concluded that the differences between the American mink and the sea mink were too minute to justify it as a separate species, and named it as a subspecies Lutreola vison antiquus. Another study conducted in 2000 refuted that study by claiming that the size range for the largest sea mink specimen was beyond that of the American mink, thereby making it a separate species.[8] However, another study in 2001 said that the size difference was insufficient evidence to classify the sea mink as its own species, and should be considered a subspecies. The study concluded that the size difference was caused by environmental factors. Furthermore, it had said that the 2000 study assumed the smaller mink specimens to be the American mink, and the larger mink specimens outside the range of the American mink to be sea minks; however, this may have been a case of sexual dimorphism wherein all specimens were sea minks, the larger being male and the smaller being female.[9] A 2007 study compared the dental makeup of the sea mink to the American mink, and said that they were distinct enough to be considered separate species.[7]

The taxonomy of minks was recently revised in 2000, resulting in the formation of a new genus Neovison which includes only the sea mink and the American mink. Formerly, both minks were classified in the genus Mustela, which is one of the largest genera in the family Mustelidae.[10]

The sea mink had various names given to it by the fur traders who hunted it, including: the water marten, the red otter, and the fisher cat. Possibly the first description of this species was made by Sir Humphrey Gilbert in the late 1500s as "a fish like a greyhound," which was a reference to its affinity to the sea and its body shape and gait which were apparently similar to that of a greyhound. It is possible that the fisher got its name from being mistakenly identified as the sea mink, which was also known as the fisher by fur traders.[11]

Range

The sea mink was a marine mammals that lived around the rocky coasts of New England and Maritime Provinces until hunted to extinction in the 19th century. Most sea mink remains are unearthed on the coast of Maine.[12] The bones of a specimen unearthed in Middleboro, Massachusetts were dated to be around 4,300±300 years old, around 19 kilometres (12 mi) from salt water. However the sea mink may have reached that area by traveling up rivers, or brought there by Native Americans. The latter is most likely as no other mink remains have been discovered between Casco Bay in Maine and southeast Massachusetts.[13] Though it is speculated that they at one point inhabited Connecticut and Rhode Island, they were commonly trapped along the coast of the Bay of Fundy (in the Gulf of Maine) and it is said that they formerly existed on the southwestern coast of Nova Scotia.[14] Sea minks bones have been unearthed in Canada, however these may have been carried there by Native Americans from the Gulf of Maine, and sea minks may not have ever inhabited Canada. The rugged shorelines of the Down East region of Maine may have represented a northernmost barrier in their range.[12] A 2000 study concluded that only American minks inhabited the mainland, and sea minks were restricted to islands off the coast, making it an example of insular gigantism. If this is the case, then all remains found on the mainland were carried there.[8] However, a 2001 study refuted that hypothesis, stating that it is unlikely that all sea mink specimens originate from one population.[9]

During the last glacial period, its range may have extended south of the Gulf of Maine, and may have even evolved there, as Maine at that time would have been covered in glaciers. However, the oldest known specimen only dates back to around 5,000 years, possibly due to the rising sea levels, and older sea mink remains may be submerged underwater. However, the sea mink may have just evolved after the last glacial period in order to occupy a new niche.[7]

Description

_(20332897078).jpg)

The sea mink was hunted to extinction before it was formally described by scientists. Subsequently, its external appearances and behaviors are not well-documented, though its relatives and descriptions given by fur traders and Native Americans give a general idea of what this animal looked like and its ecological roles. Accounts from Native Americans in the New England/Atlantic Canadian regions reported that the sea mink had a fatter body than the American mink. The sea mink produced a distinctive fishy odor, and had fur that was said to be coarser and redder than that of the American mink.[7][15] It is thought that naturalist Joseph Banks encountered this animal in 1776 in the Strait of Belle Isle, and he described it as being slightly larger than a fox, having long legs, and a tail that was long and tapered towards the end, similar to a greyhound.[11]

The sea mink was the largest of the minks. However, as only fragmentary skeletal remains of the sea mink exist, most of its external measurements are speculation and rely only on dental measurements.[16] In 1929, Ernest Seton, a wildlife artist, concluded that the probable dimensions for this animal are 914 millimetres (36 in) from head to tail with the tail being 254 millimetres (10 in) long.[17] A possible mounted sea mink specimen collected in 1894 in Connecticut measured 720 millimetres (28 in) from head to tail, with the tail being 254 millimetres (10 in) in length, however this was found to be a large American mink or possibly a hybrid by a 1966 study. It was described as having course fur that was reddish-tan in color, though much of it was faded from age most likely. It was darkest at the tail and the hind limbs, with a 50 by 15 millimetres (1.97 by 0.59 in) white patch between the forearms. There were also white spots on the left forearm and the groin region.[14]

These minks were large and heavily built, with a low sagittal crest and short, wide postorbital processes (projections on the frontal bone behind the eye sockets).[14] In fact, the most notable characteristic of the skull was its size, in that it was clearly larger than that of other mink species, having a wide rostrum, large nostril openings, large antorbital fenestrae (openings in the skull in front of the eye socket), and large teeth.[18] Their large size was probably in response to their coastal environment, as the largest subspecies of American mink, the Alaskan mink (N. v. nesolestes), inhabits the Alexander Archipelago in Alaska, an area with a habitat similar to the Gulf of Maine.[8] Since almost all members of the subfamily Mustelinae exhibit sexual dimorphism, male sea minks were probably larger than female sea minks.[7] The dentition of the sea mink suggests that their teeth were used often in crushing hard shells more so than American minks, such as the wider carnassial teeth and blunter carnassial blades.[7]

Behavior

As marine mammal species often play a large part in their ecosystems, it is possible that the sea mink was an important intertidal predator. It may have eaten seabirds, seabird eggs, and hard-bodied marine invertebrates like the American mink, though in greater proportions. Their seafood-oriented diet may have increased their size.[9] Like the American mink and the Mustela, the sea mink was probably polygynandrous, with both sexes mating with multiple individuals.[7] According to fur traders, the sea mink was nocturnal and resided in caves and rock crevices during the day.[11] Due to the overlap of American mink and sea mink ranges, it is possible that they hybridized with each other. They were not a truly marine species, being confined to coastal waters; however, the sea mink was unusually aquatic compared to other members of Musteloidea, being, next to otters, the most aquatic member of the taxon.[7]

Interactions with humans

The sea mink was pursued by fur traders due to their larger size which made them more desirable than other mink species further inland. The unregulated trade eventually led to their extinction, which is thought to have occurred anywhere from 1860 to 1920.[11][12] The sea mink was seldom sighted in the years proceeding 1860, with the last recorded kill of a sea mink in Maine made in 1880 near Jonesport, and the last known kill made in Campobello Island in New Brunswick in 1894.[11] However, the kill made in 1894 and 1880 are speculated to be large American minks.[14] Fur traders made traps to catch sea minks and also pursued them with dogs. If a sea mink were to escape into a small hole on the rocky ledges, they were dug out by hunters using shovels and crowbars. If it was out of reach of the hunters, it would be shot and then retrieved using an iron rod with a screw on the other end. If it was hiding, they would be smoked out and suffocated.[14][18] Its nocturnal behavior may have been caused from pressure by fur traders who hunted them in daylight.[11]

Since the remains of brain cases are broken and many of the bones found exhibit cut marks, it is assumed that the sea mink was hunted by Native Americans for food, and possibly for exchange and ceremonial purposes.[14][12] One study looking at the remains in shell middens in Penobscot Bay reported that sea mink craniums were intact, more so than that of other animals found, implying that they were specifically placed there.[19]

References

- ↑ Turvey, S.; Helgen, K. (2008). "Neovison macrodon". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2008. International Union for Conservation of Nature. Retrieved 6 January 2009.

- ↑ "Neovison macrodon". NatureServe Explorer. Retrieved 13 July 2017.

- ↑ Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M., eds. (2005). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 887. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- ↑ Nyakatura, K.; Bininda-Emonds, O. R. P. (2012). "Updating the evolutionary history of Carnivora (Mammalia): a new species-level supertree complete with divergence time estimates". BMC Biology. 10 (12): 12. PMC 3307490

. doi:10.1186/1741-7007-10-12.

. doi:10.1186/1741-7007-10-12. - ↑ Kays, R. W.; Wilson, D. E. (2009). Mammals of North America (2nd ed.). Boston, Massachusetts: Princeton University Press. p. 180. ISBN 978-0-6911-4092-6. OCLC 880833145.

- ↑ Prentis, D. W. (1903). "Description of an extinct mink from the shell-heaps of the Maine coast" (PDF). Proceedings of the United States National Museum. 26 (1336): 887. doi:10.5479/si.00963801.26-1336.887.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Sealfon, R. A. (2007). "Dental Divergence Supports Species Status of the Extinct Sea Mink (Neovison macrodon)". Journal of Mammalogy. 88 (2): 371–383. JSTOR 4498666. doi:10.1644/06-MMM-A-227R1.1.

- 1 2 3 Mead, J.; Spiess, A. E.; Sobolik, K. D. (2000). "Skeleton of Extinct North American Sea Mink (Mustela macrodon)". Quaternary Research. 53 (2): 247–262. Bibcode:2000QuRes..53..247M. doi:10.1006/qres.1999.2109.

- 1 2 3 Graham, R. (2001). "Comment on "Skeleton of Extinct North American Sea Mink (Mustela macrodon)" by Mead et al.". Quaternary Research. 56 (3): 419–421. Bibcode:2001QuRes..56..419G. doi:10.1006/qres.2001.2266.

- ↑ Abramov, A. V. (2000). "A taxonomic review of the genus Mustela (Mammalia, Carnivora)" (PDF). Zoosystematica Rossica. 8: 357–364.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Mowat, F. (2012) [1984]. Sea of Slaughter. Vancouver, British Columbia: Douglas and McIntyre. pp. 160–164. ISBN 978-1-77100-046-8. OCLC 879632158.

- 1 2 3 4 Black, D. W.; Reading, J. E.; Savage, H. G. (1998). "Archaeological Records of the Extinct Sea Mink, Mustela macrodon (Carnivora: Mustelidae), from Canada" (PDF). Canadian Field-Naturalist. 112 (1): 45–49.

- ↑ Waters, J. H.; Ray, C. E. (1961). "Former Range of the Sea Mink". Journal of Mammalogy. 42 (3): 380–383. doi:10.2307/1377035.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Manville, R. H. (1966). "The Extinct Sea Mink, With Taxonomic Notes" (PDF). Proceedings of the United States National Museum. 122 (3584): 1–12. doi:10.5479/si.00963801.122-3584.1.

- ↑ Day, David (1981). The Encyclopedia of Vanished Species. London: Universal Books Ltd. p. 220. ISBN 978-0-947889-30-2.

- ↑ Mead, J. I.; Spiess, A. E. (2001). "Reply to Russell Graham about Mustela macrodon". Quaternary Research. 56 (3): 422–423. Bibcode:2001QuRes..56..422M. doi:10.1006/qres.2001.2268.

- ↑ Seton, E. T. (1929). Lives of Game Animals. 2. Doubleday, Doran. p. 562. OCLC 872457192.

- 1 2 Hollister, N. (1965). "A synopsis of the American minks". Proceedings of the United States National Museum. 44 (1965): 478–479. doi:10.5479/si.00963801.44-1965.471.

- ↑ Bourque, B. J. (1995). Diversity and Complexity in Prehistoric Maritime Societies: A Gulf Of Maine Perspective. New York, New York: Plenum Press. p. 341. ISBN 978-0-306-44874-4.

The Mustela macrodon cranium is much more complete than those from the rest of the midden, adding to the impression that these bones were placed especially in the cache.

External links

| Wikispecies has information related to: Neovison |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Neovison macrodon. |