Sea Dragon (rocket)

The Sea Dragon was a 1962 conceptualized design study for a two-stage sea-launched orbital super heavy-lift launch vehicle. The project was led by Robert Truax while working at Aerojet, one of a number of designs he created that were to be launched by floating the rocket in the ocean. Although there was some interest at both NASA and Todd Shipyards, the project was not implemented. At the massive dimensions of 150 m (490 ft) long and 23 m (75 ft) in diameter, Sea Dragon would have been the largest rocket ever built, it still is the by far the largest rocket ever fully conceived.

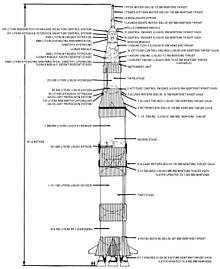

Design

Truax's basic idea was to produce a low-cost heavy launcher, a concept now called "big dumb booster". To lower the cost of operation, the rocket itself was launched from the ocean, requiring little in the way of support systems. A large ballast tank system attached to the bottom of the first-stage engine bell was used to "hoist" the rocket vertical for launch. In this orientation the cargo at the top of the second stage was just above the waterline, making it easy to access. Truax had already experimented with this basic system in the Sea Bee[1][NB 1] and Sea Horse[2][NB 2] To lower the cost of the rocket, he intended it to be built of inexpensive materials, specifically 8 mm steel sheeting. The rocket would be built at a sea-side shipbuilder and towed to sea for launch. It would use wide engineering margins with strong simple materials to further enhance reliability and reduce cost of complexity. The system would be at least partially reusable with passive reentry and recovery of rocket sections for refurbishment and relaunch.[3][4]

The first stage was to be powered by a single enormous 36,000,000 kgf (350 MN; 79,000,000 lbf) thrust engine burning RP-1 and LOX (liquid oxygen). The fuels were pushed into the engine by liquid nitrogen, which provided a pressure of 32 atm (3,200 kPa; 470 psi) for the RP-1 and 17 atm (1,700 kPa; 250 psi) for the LOX, providing a total pressure in the engine of 20 atm (2,000 kPa; 290 psi) at takeoff. As the vehicle climbed the pressures dropped off, eventually burning out after 81 seconds. By this point the vehicle was 25 miles (40 km) up and 20 mi (32 km) downrange, traveling at a speed of 4,000 mph (6,400 km/h; 1.8 km/s). The normal mission profile expended the stage in a high-speed splashdown some 180 miles (290 km) downrange. Plans for stage recovery were studied as well.

The second stage was also equipped with a single very large engine, in this case a 6,000,000 kgf (59 MN; 13,000,000 lbf) thrust engine burning liquid hydrogen and LOX. Although also pressure-fed, at a constant lower pressure of 7 atm (710 kPa; 100 psi) throughout the entire 260 second burn, at which point it was 142 mi (229 km) up and 584 mi (940 km) downrange. To improve performance, the engine featured an expanding engine bell, changing from 7:1 to 27:1 expansion as it climbed. The overall height of the rocket was shortened somewhat by making the "nose" of the first stage pointed, lying inside the second stage engine bell.

A typical launch sequence would start with the rocket being refurbished and mated to its cargo and ballast tanks on shore. The RP-1 and nitrogen would also be loaded at this point. The rocket would then be towed to a launch site, where the LOX and LH2 would be generated on-site using electrolysis; Truax suggested using a nuclear-powered aircraft carrier as a power supply during this phase. The ballast tanks, which also served as a cap and protection for the first stage engine bell, would then be filled with water, raising the rocket to vertical. Last minute checks could then be carried out, and the rocket launched.

The rocket would have been able to carry a payload of up to 550 tonnes (540 long tons; 610 short tons) or 550,000 kg (1,210,000 lb) into low Earth orbit. Payload costs were estimated to be between $59 to $600 per kg. TRW (Space Technology Laboratories, Inc.) conducted a program review and validated the design and its expected costs,[5] apparently a surprise to NASA. However, budget pressures led to the closing of the Future Projects Branch, ending work on the super-heavy launchers they had proposed for a manned mission to Mars.

See also

Notes

- ↑ Sea Bee was a proof of principle program to validate the sea-launch concept. A surplus Aerobee rocket was modified so that it could be fired underwater. The rocket worked properly the first time in restrained mode. Later tests of repeat firings proved so simple that the cost of turn-around was about 7% that of a new unit.

- ↑ Sea Horse demonstrated sea-launch at a larger scale and on a rocket with a complex set of guidance and control systems. It used a surplus 9,000 kgf (20,000 lbf; 88,000 N) pressure fed, acid/aniline Corporal missile on a barge in San Francisco Bay. This was first fired several metres above the water, then lowered and fired in successive steps until reaching a considerable depth. Firing from underwater posed no problems, and there was substantial noise attenuation.

References

- ↑ Astronautix.com, Sea Bee

- ↑ Astronautix.com, Sea Horse

- ↑ David Grossman (3 April 2017). "The Enormous Sea-Launched Rocket That Never Flew". Popular Mechanics.

- ↑ "The Legend of the Sea Dragon". Citizens in Space. January 2013.

- ↑ “Study of Large Sea-Launch Space Vehicle,” Contract NAS8-2599, Space Technology Laboratories, Inc./Aerojet General Corporation Report #8659-6058-RU-000, Vol. 1 – Design, January 1963

- Astronautix.com, Sea Dragon

- Truax Engineering Multimedia Archive

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sea Dragon. |

- Truax Engineering Multimedia Archive

- Sea Dragon Concept Volume 1 (Summary), LRP 297 (NASA-CR-52817), 1963-01-28.

- Sea Dragon Concept Volume 3 (Preliminary program plan), LRP 297 (NASA-CR-51034), 1963-02-12.

- Encyclopedia Astronautica, Sea Dragon

- Big Dumb Rockets

- YouTube, Sea Dragon - 8.14 TMRO - Interview show about "Sea Dragon"

- Search "Sea Dragon Concept" at the NASA Technical Report Server to read the unclassified design study:

- Sea Dragon Concept Volume 1 (Summary), LRP 297 (NASA-CR-52817), 1963-01-28.

- Sea Dragon Concept Volume 3 (Preliminary program plan), LRP 297 (NASA-CR-51034), 1963-02-12.