Hyoscine

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Transdermscop, Kwells, others |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| Pregnancy category | |

| Routes of administration | by mouth, skin patch, eye drops, subcutaneous, intravenous, sublingual, rectal, buccal transmucousal, intramuscular |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Metabolism | Liver |

| Biological half-life | 4.5 hours[1] |

| Excretion | Kidney |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| Synonyms | hyoscine hydrobromide, scopolamine hydrobromide |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.083 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

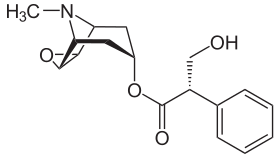

| Formula | C17H21NO4 |

| Molar mass | 303.353 g/mol |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| | |

Hyoscine, also known as scopolamine,[2] is a medication used to treat motion sickness and postoperative nausea and vomiting. It is also sometimes used before surgery to decrease saliva. When used by injection, effects begin after about 20 minutes and last for up to 8 hours. It may also be used by mouth and as a skin patch.[3]

Common side effects include sleepiness, blurred vision, dilated pupils, and dry mouth. It is not recommended in people with glaucoma or bowel obstruction.[3] It is unclear if use during pregnancy is safe; however, it appears to be safe during breastfeeding.[4] Hyoscine is in the antimuscarinic family of medications and works by blocking some of the effects of acetylcholine within the nervous system.[3]

Hyoscine was first written about in 1881 and came into medical use in 1947.[5] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines, the most effective and safe medicines needed in a health system.[6] Hyoscine is produced from plants of the nightshade family.[7] The name "scopolamine" is derived from one type of nightshade known as Scopolia while "hyoscine" is from another type known as Hyoscyamus niger.[8][9]

Medical use

Hyoscine has a number of uses in medicine, where it is used to treat the following:[10][11]

- Postoperative nausea and vomiting and sea sickness, leading to its use by scuba divers[12][13]

- Motion sickness (where it is often applied as a transdermal patch behind the ear)

- Gastrointestinal spasms

- Renal or biliary spasms

- Aid in gastrointestinal radiology and endoscopy

- Irritable bowel syndrome

- Clozapine-induced hypersalivation (drooling)

- Bowel colic

- Eye inflammation[14]

It is sometimes used as a premedication (especially to reduce respiratory tract secretions) to surgery, mostly commonly by injection.[10][11]

Pregnancy

Scopolamine crosses the placenta and is a pregnancy category C medication, meaning a risk to the fetus cannot be ruled out. Either studies in animals have revealed adverse effects on the fetus (teratogenic or embryocidal effects or other) and no controlled studies in women have been made, or studies in women and animals are not available. Drugs should be given only if the potential benefits justify the potential risk to the fetus. It may cause respiratory depression and/or neonatal hemorrhage when used during pregnancy, and some animal studies did report adverse events. Transdermal scopolamine has been used as an adjunct to epidural anesthesia for Caesarean delivery without adverse CNS effects on the newborn. Except when used prior to Caesarean section, it should only be used during pregnancy if the benefit to the mother outweighs the potential risk to the fetus.

Breastfeeding

Scopolamine enters breast milk by secretion. Although no human studies exist to document the safety of scopolamine while nursing, the manufacturer recommends that caution be taken if scopolamine is administered to a breastfeeding woman.[15]

Elderly

The likelihood of experiencing adverse effects from scopolamine is increased in the elderly relative to younger people. This phenomenon is especially true for older people who are also on several other medications. It is recommended that scopolamine use should be avoided in this age group because of these potent anticholinergic adverse effects.[16]

Adverse effects

Adverse effect incidence:[17][18][19][20]

Uncommon (0.1–1% incidence) adverse effects include:

- Dry mouth

- Dyshidrosis (reduced ability to sweat in order to cool off)

- Tachycardia (usually occurs at higher doses and is succeeded by bradycardia)

- Bradycardia

- Urticaria (hives)

- Pruritus (itching)

Rare (<0.1% incidence) adverse effects include:

- Constipation

- Urinary retention

- Hallucinations

- Agitation

- Confusion

- Restlessness

- Seizures

Unknown frequency adverse effects include:

- Anaphylactic shock

- Anaphylactic reactions

- Dyspnea (shortness of breath)

- Rash

- Erythema

- Other hypersensitivity reactions

- Blurred vision

- Mydriasis (dilated pupils)

- Drowsiness

- Dizziness

- Somnolence

Overdose

Physostigmine is an acetylcholinesterase inhibitor that readily crosses the blood-brain barrier, and has been used as an antidote to treat the central nervous system depression symptoms of a scopolamine overdose.[21] Other than this supportive treatment, gastric lavage and induced emesis (vomiting) are usually recommended as treatments for oral overdoses.[20] The symptoms of overdose include:[19][20]

- Tachycardia

- Arrhythmia

- Blurred vision

- Photophobia

- Urinary retention

- Drowsiness or paradoxical reaction which can present with hallucinations

- Cheyne-Stokes respiration

- Dry mouth

- Skin reddening

- Inhibition of gastrointestinal motility

Hospitalizations

About one in five emergency room admissions for poisoning in Bogotá, Colombia, have been attributed to scopolamine.[22] Most commonly, the victim has been poisoned by a robber that gave the victim a scoplamine-laced beverage, in the hope that the victim would become unconscious or unable to effectively resist the robbery.[22] In June 2008, more than 20 people were hospitalized with psychosis in Norway after ingesting counterfeit Rohypnol tablets containing scopolamine.[23]

Interactions

Due to interactions with metabolism of other drugs, scopolamine can cause significant unwanted side effects when taken with other medications. Specific attention should be paid to other medications in the same pharmacologic class as scopolamine, also known as anticholinergics. The following medications could potentially interact with the metabolism of scopolamine: analgesics/pain medications, ethanol, zolpidem, thiazide diuretics, buprenorphine, anticholinergic drugs such as tiotropium, etc.

Route of administration

Scopolamine can be taken by mouth, subcutaneously, ophthalmically and intravenously, as well as via a transdermal patch.[24] The transdermal patch (e.g., Transderm Scōp) for prevention of nausea and motion sickness employs scopolamine base, and is effective for up to three days.[25] The oral, ophthalmic, and intravenous forms have shorter half-lives and are usually found in the form scopolamine hydrobromide (for example in Scopace, soluble 0.4 mg tablets or Donnatal).

NASA is currently developing a nasal administration method. With a precise dosage, the NASA spray formulation has been shown to work faster and more reliably than the oral form.[26]

Mechanism of action

Although it is usually referred to as a nonspecific antimuscarinic,[27] there is indirect evidence for m1-receptor subtype specificity.[28]

Biosynthesis in plants

Scopolamine is among the secondary metabolites of plants from Solanaceae (nightshade) family of plants, such as henbane, jimson weed (Datura), angel's trumpets (Brugmansia), and corkwood (Duboisia).[29][8]

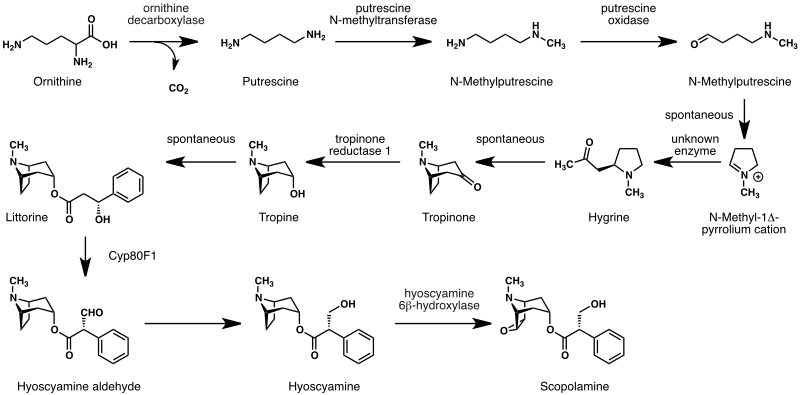

The biosynthesis of scopolamine begins with the decarboxylation of L-ornithine to putrescine by ornithine decarboxylase. Putrescine is methylated to N-methylputrescine by putrescine N-methyltransferase.[30]

A putrescine oxidase that specifically recognizes methylated putrescine catalyzes the deamination of this compound to 4-methylaminobutanal, which then undergoes a spontaneous ring formation to N-methyl-pyrrolium cation. In the next step, the pyrrolium cation condenses with acetoacetic acid yielding hygrine. No enzymatic activity could be demonstrated to catalyze this reaction. Hygrine further rearranges to tropinone.[30]

Subsequently, tropinone reductase I converts tropinone to tropine which condenses with phenylalanine-derived phenyllactate to littorine. A cytochrome P450 classified as Cyp80F1[31] oxidizes and rearranges littorine to hyoscyamine aldehyde. In the final step, hyoscyamine undergoes epoxidation catalyzed by 6beta-hydroxyhyoscyamine epoxidase yielding scopolamine.[30]

History

One of the earlier alkaloids isolated from plant sources, scopolamine has been in use in its purified forms (such as various salts, including hydrochloride, hydrobromide, hydroiodide and sulfate), since its isolation by the German scientist Albert Ladenburg in 1880, and as various preparations from its plant-based form since antiquity and perhaps prehistoric times. Following the description of the structure and activity of scopolamine by Ladenburg, the search for synthetic analogues of and methods for total synthesis of scopolamine and/or atropine in the 1930s and 1940s resulted in the discovery of diphenhydramine, an early antihistamine and the prototype of its chemical subclass of these drugs, and pethidine, the first fully synthetic opioid analgesic, known as Dolatin and Demerol amongst many other trade names.

Scopolamine was used in conjunction with morphine, oxycodone, or other opioids from before 1900 into the 1960s to put mothers in labor into a kind of "twilight sleep". The analgesia from scopolamine plus a strong opioid is deep enough to allow higher doses to be used as a form of anaesthesia.

Scopolamine mixed with oxycodone (Eukodal) and ephedrine was marketed by Merck as SEE (from the German initials of the ingredients) and Scophedal starting in 1928, and the mixture is sometimes mixed on site on rare occasions in the area of its greatest historical usage, namely Germany and Central Europe.

Scopolamine was also one of the active ingredients in Asthmador, an over-the-counter (OTC) smoking preparation marketed in the 1950s and 1960s claiming to combat asthma and bronchitis. In November 1990, the US Food and Drug Administration forced OTC products with scopolamine and several hundred other ingredients that had allegedly not been proved effective off the market. Scopolamine shared a small segment of the OTC sleeping pill market with diphenhydramine, phenyltoloxamine, pyrilamine, doxylamine, and other first-generation antihistamines, many of which are still used for this purpose in drugs such as Sominex, Tylenol PM, NyQuil, etc.

Society and culture

Names

Hyoscine hydrobromide is the International Nonproprietary Name, and scopolamine hydrobromide is the United States Adopted Name. Other names include levo-duboisine, devil's breath and burundanga.[22]

Recreational use

While it has been occasionally used recreationally for its hallucinogenic properties, the experiences are often unpleasant, mentally and physically. It is also physically dangerous, so repeated use is rare.[32]

Interrogation

The effects of scopolamine were studied for use as a truth serum in interrogations in the early 20th century,[33] but because of the side effects, investigations were dropped.[34] In 2009, it was proven that Czechoslovak communist state security secret police used scopolamine at least three times to obtain confessions from alleged antistate conspirators.[35]

Crime

In 1910, scopolamine was detected in the remains believed to be those of Cora Crippen, wife of Dr. Hawley Harvey Crippen, and was accepted at the time as the cause of her death, since her husband was known to have bought some at the start of the year.[36]

The drug is known to produce loss of memory of events immediately before exposure and sleepiness, similar to the effect of benzodiazepines or alcohol poisoning, which affects the ability of a person to resist criminal aggression. A travel advisory published by the United States Department of State in 2012 stated:

One common and particularly dangerous method that criminals use in order to rob a victim is through the use of drugs. The most common [in Colombia] has been scopolamine. Unofficial estimates put the number of annual scopolamine incidents in Colombia at approximately 50,000. Scopolamine can render a victim unconscious for 24 hours or more. In large doses, it can cause respiratory failure and death. It is most often administered in liquid or powder form in foods and beverages. The majority of these incidents occur in night clubs and bars, and usually men, perceived to be wealthy, are targeted by young, attractive women. To avoid becoming a victim of scopolamine, one should never accept food or beverages offered by strangers or new acquaintances or leave food or beverages unattended. Victims of scopolamine or other drugs should seek immediate medical attention.[37]

Beside robberies it is also allegedly involved in express kidnappings and sexual assault.[38] The Hospital Clínic in Barcelona introduced a special protocol in 2008 to help medical workers identify cases, while Madrid hospitals adopted a similar working document in February 2015.[38] However, Hospital Clínic has found little scientific evidence to support this use and relies on the victims' stories to reach any conclusion.[38] Although poisoning by scopolamine appears quite often in the media as an aid for raping, kidnapping, killing or robbery, the effects of this drug and the way it is applied by criminals (added to drinks, transdermal injection, on playing cards and papers etc.) are often exaggerated,[39][40][41] especially the transdermal uses, as the dose that can be absorbed by the skin is too low to have any effect[38] (scopolamine transdermal patches must be used for hours to days).[24]

The name "burundanga" derives from being an extract of the brugmansia plant.[42]

Research

Scopolamine has been used as a research tool to study the involvement of acetylcholine in cognition. Results in primates suggest that acetylcholine is involved in the encoding of new information into long term memory.[43] Scopolamine has also been investigated as an antidepressant with a number of small studies finding positive results.[44][45][46][47]

References

- ↑ Putcha, L.; Cintrón, N. M.; Tsui, J.; Vanderploeg, J. M.; Kramer, W. G. (1989). "Pharmacokinetics and Oral Bioavailability of Scopolamine in Normal Subjects". Pharmacology Research. 6 (6): 481–485. PMID 2762223. doi:10.1023/A:1015916423156.

- ↑ Juo, Pei-Show (2001). Concise Dictionary of Biomedicine and Molecular Biology. (2nd ed.). Hoboken: CRC Press. p. 570. ISBN 9781420041309.

- 1 2 3 "Scopolamine". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- ↑ "Scopolamine Use During Pregnancy | Drugs.com". www.drugs.com. Retrieved 15 December 2016.

- ↑ Fischer, Janos; Ganellin, C. Robin (2006). Analogue-based Drug Discovery. John Wiley & Sons. p. 551. ISBN 9783527607495.

- ↑ "WHO Model List of Essential Medicines (19th List)" (PDF). World Health Organization. April 2015. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- ↑ Osbourn, Anne E.; Lanzotti, Virginia (2009). Plant-derived Natural Products: Synthesis, Function, and Application. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 5. ISBN 9780387854984.

- 1 2 The Chambers Dictionary. Allied Publishers. 1998. pp. 788, 1480. ISBN 978-81-86062-25-8.

- ↑ Cattell, Henry Ware (1910). Lippincott's new medical dictionary: a vocabulary of the terms used in medicine, and the allied sciences, with their pronunciation, etymology, and signification, including much collateral information of a descriptive and encyclopedic character. Lippincott. p. 435. Retrieved 25 February 2012.

- 1 2 Joint Formulary Committee (2013). British National Formulary (BNF) (65 ed.). London, UK: Pharmaceutical Press. pp. 49, 266, 822, 823. ISBN 978-0-85711-084-8.

- 1 2 Rossi, S, ed. (2013). Australian Medicines Handbook (2013 ed.). Adelaide: The Australian Medicines Handbook Unit Trust. ISBN 978-0-9805790-9-3.

- ↑ Bitterman, N.; Eilender, E.; Melamed, Y. (1991). "Hyperbaric Oxygen and Scopolamine". Undersea Biomedical Research. 18 (3): 167–174. PMID 1853467. Retrieved 2008-08-13.

- ↑ Williams, T. H.; Wilkinson, A. R.; Davis, F. M.; Frampton, C. M. (1988). "Effects of Transcutaneous Scopolamine and Depth on Diver Performance". Undersea Biomedical Research. 15 (2): 89–98. PMID 3363755.

- ↑ http://www.medicinenet.com/scopolamine_drops-ophthalmic/article.htm

- ↑ Briggs (1994). Drugs in Pregnancy and Lactation. Baltimore, MD: Williams and Wilkins. pp. 777–778.

- ↑ Flicker; Ferris (1992). "Hypersensitivity to scopolamine in the elderly". Psychopharmacology (Berl). 107 (2–3): 437–441. PMID 1615141. doi:10.1007/bf02245172.

- ↑ "TRANSDERM SCOP (scopalamine) patch, extended release [Baxter Healthcare Corporation]". DailyMed. Baxter Healthcare Corporation. April 2013. Retrieved 22 October 2013.

- ↑ "DBL™ HYOSCINE INJECTION BP". TGA eBusiness Services. Hospira Australia Pty Ltd. 30 January 2012. Retrieved 22 October 2013.

- 1 2 "Buscopan Tablets - Summary of Product Characteristics (SPC)". electronic Medicines Compendium. Boehringer Ingelheim Limited. 11 September 2013. Retrieved 22 October 2013.

- 1 2 3 "Kwells 300 microgram tablets - Summary of Product Characteristics". electronic Medicines Compendium. Bayer plc. 7 January 2008. Retrieved 22 October 2013.

- ↑ Paul G. Barash; et al., eds. (2009). Clinical anesthesia (6 ed.). Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 346. ISBN 978-0-7817-8763-5.

- 1 2 3 Uribe-Granja, Manuel; Moreno-López, Claudia L.; Zamora S., Adriana; Acosta, Pilar J. (September 2005). "Perfil epidemiológico de la intoxicación con burundanga en la clínica Uribe Cualla S. A. de Bogotá, D. C" (pdf). Acta Neurológica Colombiana (in Spanish). 21 (3): 197–201.

- ↑ "Bilsykemedisin i falske rohypnol-tabletter". Aftenposten.no. Archived from the original on 27 June 2008.

- 1 2 White, P. F.; Tang, J.; Song, D.; et al. (2007). "Transdermal Scopolamine: An Alternative to Ondansetron and Droperidol for the Prevention of Postoperative and Postdischarge Emetic Symptoms". Anesthesia and Analgesia. 104 (1): 92–96. PMID 17179250. doi:10.1213/01.ane.0000250364.91567.72.

- ↑ "Transderm Scop patch prescribing information".

- ↑ "NASA Signs Agreement to Develop Nasal Spray for Motion Sickness".

- ↑ https://scholar.google.com/scholar?q=scopolamine+nonselective&btnG=&hl=en&as_sdt=0%2C11

- ↑ Burke, RE (1986). "The relative selectivity of anticholinergic drugs for the M1 and M2 muscarinic receptor subtypes.". Movement Disorders. 1 (2): 135–144. PMID 2904117. doi:10.1002/mds.870010208.

- ↑ Muranaka, T.; Ohkawa, H.; Yamada, Y. (1993). "Continuous Production of Scopolamine by a Culture of Duboisia leichhardtii Hairy Root Clone in a Bioreactor System". Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology. 40 (2–3): 219–223. doi:10.1007/BF00170370.

- 1 2 3 Ziegler J, Facchini PJ (2008). "Alkaloid biosynthesis: metabolism and trafficking". Annual Review of Plant Biology. 59 (1): 735–69. PMID 18251710. doi:10.1146/annurev.arplant.59.032607.092730.

- ↑ Li R, Reed DW, Liu E, Nowak J, Pelcher LE, Page JE, Covello PS (May 2006). "Functional genomic analysis of alkaloid biosynthesis in Hyoscyamus niger reveals a cytochrome P450 involved in littorine rearrangement". Chemistry & Biology. 13 (5): 513–20. PMID 16720272. doi:10.1016/j.chembiol.2006.03.005.

- ↑ Freye, E. (2010). "Toxicity of Datura Stramonium". Pharmacology and Abuse of Cocaine, Amphetamines, Ecstasy and Related Designer Drugs. Netherlands: Springer. pp. 217–218. ISBN 978-90-481-2447-3. doi:10.1007/978-90-481-2448-0_34.

- ↑ House, R. E. (September 1922). "The Use of Scopolamine in Criminology". Texas State Journal of Medicine. 18: 256–263.

Reprinted in: House, Robert E. (July–August 1931). "The Use of Scopolamine in Criminology". American Journal of Police Science. Northwestern University School of Law. 2 (4): 328–336. JSTOR 1147361. doi:10.2307/1147361. - ↑ Bimmerle, George (September 22, 1993). "'Truth' Drugs in Interrogation". Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved June 14, 2012.

- ↑ Gazdík, J.; Navara, L. (August 8, 2009). "Svědek: Grebeníček vězně nejen mlátil, ale dával jim i drogy" [A witness: Grebeníček not only beat prisoners, he also administered drugs to them] (in Czech). iDnes. Retrieved August 10, 2009.

- ↑ Young, Filson, ed. (1920). The Trial of Hawley Harvey Crippen. Notable Trials Series. Edinburgh: William Hodge & Company. p. xxvii; see also evidence, pp. 68–77. OCLC 22125100. Retrieved August 6, 2015.

- ↑ "Colombia 2012 Crime and Safety Report: Cartagena". Overseas Security Advisory Council, United States Department of State. March 4, 2012. Retrieved August 6, 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 Domínguez, Iñigo (25 July 2016). "Burundanga: the stealth drug that cancels the victim’s willpower". Crime. El País, Madrid. Retrieved 12 August 2016.

- ↑ ""Burundanga Business Card Drug Warning". Hoax-Slayer.com.".

- ↑ "Beware the Burundanga Man!". About.com Entertainment. Retrieved 2016-12-19.

- ↑ Mikkelson, David. "Burundanga/Scopolamine Warning". snopes. Retrieved 2016-12-19.

- ↑ Vaughan Bell (3 March 2011). "Mind controller: What is the 'burundanga' drug?". Wired UK (published April 2011).

- ↑ Ridley, R. M.; et al. (1984). "An involvement of acetylcholine in object discrimination learning and memory in the marmoset". Neuropsychologia. 22: 253–263. doi:10.1016/0028-3932(84)90073-3.

- ↑ Drevets, WC; Zarate CA, Jr; Furey, ML (15 June 2013). "Antidepressant effects of the muscarinic cholinergic receptor antagonist scopolamine: a review.". Biological Psychiatry. 73 (12): 1156–63. PMC 4131859

. PMID 23200525. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.09.031.

. PMID 23200525. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.09.031. - ↑ Hasselmann, H (2014). "Scopolamine and depression: a role for muscarinic antagonism?". CNS & neurological disorders drug targets. 13 (4): 673–83. PMID 24938776. doi:10.2174/1871527313666140618105710.

- ↑ Jaffe, RJ; Novakovic, V; Peselow, ED (2013). "Scopolamine as an antidepressant: a systematic review.". Clinical neuropharmacology. 36 (1): 24–6. PMID 23334071. doi:10.1097/wnf.0b013e318278b703.

- ↑ Wohleb ES, Wu M, Gerhard DM, Taylor SR, Picciotto MR, Alreja M, Duman RS (2016). "GABA interneurons mediate the rapid antidepressant-like effects of scopolamine". J. Clin. Invest. 126: 2482–94. PMID 27270172. doi:10.1172/JCI85033.