Ludwigsburg Palace

- This article is about the residential palace. For the other two palaces on the grounds, see Monrepos and Schloss Favorite, Ludwigsburg. For the city, see Ludwigsburg.

| Ludwigsburg Palace | |

|---|---|

| German: Residenzschloss Ludwigsburg | |

|

Arms of the Duchy of Württemberg, circa 1773 | |

|

Ludwigsburg Palace's new corps de logis, or New Hauptbau, and the Blooming Baroque gardens from the south. | |

| Alternative names | "Versailles of Swabia"[1] |

| Etymology | Castle and residence of Eberhard Ludwig, Duke of Württemberg |

| General information | |

| Status | Complete |

| Type | Palace |

| Architectural style | Baroque, Rococo, Empire |

| Location | Ludwigsburg district, Stuttgart region |

| Address | Schlossstraße 30, 71634 Ludwigsburg |

| Town or city | Ludwigsburg, Germany |

| Coordinates | 48°54′0″N 9°11′45″E / 48.90000°N 9.19583°ECoordinates: 48°54′0″N 9°11′45″E / 48.90000°N 9.19583°E |

| Construction started | 1704 |

| Completed | 1733 |

| Cost | 3,000,000 florins[2] |

| Client |

Eberhard Louis, Duke of Württemberg Charles Eugene, Duke of Württemberg Frederick I of Württemberg |

| Affiliation |

Duchy of Württemberg Kingdom of Württemberg |

| Grounds | 32 ha (79 acres)[3] |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect |

Philipp Joseph Jenisch Johann Friedrich Nette Donato Giuseppe Frisoni Philippe de La Guêpière Friedrich Thouret |

| Known for | Residence of the Dukes of Württemberg |

| Other information | |

| Number of rooms | 452[4] |

| Website | |

|

www | |

Ludwigsburg Palace (German: Residenzschloss Ludwigsburg) is a massive, Baroque palace complex located in Ludwigsburg, Germany, about 12 kilometres (7.5 mi) from the Baden-Württemberg state capital of Stuttgart. The palace complex, nicknamed the "Versailles of Swabia"[1] is one of the largest Baroque palaces in Germany, and one of its most prominent features is the enormous garden around the palace of the same style. Today, its sumptuous interiors contain various museums and tourist shops.

The castle is surrounded on three sides by a massive garden, the Blühendes Barock (or "Blooming Baroque") that was arranged according to how it might have appeared around 1800 in 1954, the 250th anniversary of the start of construction on Ludwigsburg. Also on the grounds are the ancillary residencies of Monrepos and Schloss Favorite, which complete the grounds of this regional tourist attraction. Altogether, the gardens, sumptuous interiors complete with original furnishing, and the architecture altogether tell the tale of four distinct epochs of art and architecture: the Baroque, Rococo, Neoclassical, and Empire eras.

History

Background

In the days before the palace of the 17th century, a hunting property with a falconry stood on the site of the current palace before it was razed in 1697[5] followed by the Ducal residence in Stuttgart in 1707 by French soldiers.[6] A few years later, the Duke of Württemberg, Eberhard Louis, visited France and especially Paris and the court of French king Louis XIV at the Palace of Versailles and was so inspired that he,[7] like many other German princes, decided to build a new baroque palace in Versaille's image to reflect his own dreams of an absolutist Württemberg,[8] despite the fact that he couldn't bring all the aristocracy to this new palace as Louis XIV had when he fled from the possibility of another Fronde.[6] Among other reasons for the Duke's decision to construct this new palace in the countryside around Stuttgart was his desire to rebuild his lost hunting retreat (German: Jagdschloss) and to get away from his wife to establish a court for his mistress and foreign courtier, Wilhelmine von Grävenitz, a result of his need to attract aristocratic visitors.[9] So it was that master builder Philipp Joseph Jenisch was commissioned to design and construct a new hunting retreat and pleasure palace for Eberhard Louis,[10] who himself laid the foundation of what would become the largest Baroque palace in Germany in 1704 (the same year as the Battle of Blenheim, in which Eberhard Louis participated[6]). The next year, Eberhard Louis, in German Eberhard Ludwig, christened his new palace "Ludwigsburg,"[11] literally "Ludwig's castle."

Construction

Jenisch worked on the palace for two years, only managing to construct the ground floor and walls of the planned hunting lodge that later became the old corps de logis and most of the southern gardens, before being replaced by the new and experienced court architect, Johann Fredrich Nette, when the duke lost faith in Jenisch's ability as an architect and hired Nette in 1707.[11] This would be the first time a non-native of Württemberg would lead work on the palace.[10] Nette completed the old corp de logis, the Old Hauptbau, but began drawing up new plans based on his experience with Bohemian Baroque. Nette erected two new buildings: the play and hunting pavilions, constructed from 1707 to 1716. Then, and to the indignation of the Ducal court,[5] he linked the old corps de logis and the pavilions with two new wings, creating his desired three-wing system.[11] For the upcoming construction on the interiors of the palace, Nette traveled to Prague and there recruited architect and stuccoist Donato Giuseppe Frisoni in 1709.[12][13] Nette had completed most of the northern gardens by 1714, freeing him up for a trip to Paris once the War of the Spanish Succession ended the following year with the Treaty of Utrecht. Unfortunately, on his way back from Paris to Ludwigsburg, he died suddenly from a stroke, aged 41.[12]

Ever following the model of Versailles and needing a new city to service the needs of his palace,[14] Eberhard Louis desired to build the ideal baroque city to encompass his palace as a symbol of his power and prestige.[15] To this end, he charged Donato Frisoni with its design and construction began in 1704. Unlike many fellow German princes, instead of raising new taxes or simply increasing them, he allowed the workers to live on the land around.[4] Starting in 1709, the Duke began inviting people to come live in his city, enticing potential settlers with offers of free land, financing for construction materials, 15 years without taxation and, later, complete freedom of religion and occupation.[16] However, actual construction in the city stalled until the duke first swore that he would reside in the palace at the center of the city,[15] and then second granted Ludwigsburg status as a city and declared it his capital in 1718.[16] The construction of the opulent Schlosskapelle in 1716 by Donato Frisoni shows that the Duke was fully willing to commit to this pledge even before making the city his capital.[17]

That same year, Duke Eberhard Louis appointed Donato Frisoni, who had no formal training in architecture, as lead architect on the site of the palace in addition to the city of Ludwigsburg despite opposition from the palatial building commission.[18] He mostly continued the work of Nette, but made his own additions to Nette's plans, such as the two chapels facing each other on the east and west sides of the palace, the two Cavalier halls on the east and west wings in 1722,[11] the Palace Theater (1729-1733),[19] and the palace's cleverly hidden servant passages and residences.[20] Frisoni also made additions to the preexisting palace, adding the mansard roof to the top of the Old Hauptbau because of water damage caused by its initially flat roof in 1719.[21] However, Frisoni's most important addition was the new corps de logis which, on the orders of the Duke himself, was constructed from 1724 to 1733 because the old corps de logis was too small for his ceremonies. This new main structure, the New Hauptbau, and the east and west wings of the palace were completed in 1733.[11] Meanwhile, Frisoni built what has been hailed as "the ideal Baroque city," and dedicated its main square, flanked by two large Protestant and Catholic churches, to the city's founder and namesake, Duke Eberhard Louis.[18]

Usage

In the 1740s a New Palace was built in Stuttgart, and it was favored by the later dukes of Württemberg as their primary residence, but Ludwigsburg remained in use as well. However, under King William I of Württemberg, the palace, and especially the gardens, gradually decayed because William I, in contrast to his predecessors, showed no interest in Ludwigsburg. He favored his own palatial projects at Wilhelma (Moorish) and Rosenstein (Neoclassical) in Stuttgart.

Duke Charles Eugene moved the official residence of the Dukes from Stuttgart from the Old Castle (official residence of the Dukes in the 15th century) in Stuttgart after calling it "prison-like."[5] From the castle's construction to the death of Duke Charles Eugene, Ludwigsburg served as the ducal palace and seat of power in Württemberg for a total of 28 years.[22]

With Duke Eberhard Louis's death, ascension of his cousin Charles Alexander, and move of power back to Stuttgart by Duke Charles Alexander, the population of Ludwigsburg was reduced by half and did not return to its original size until Duke Charles Eugene moved the capital back to Ludwigsburg in 1764.[16]

King Frederick assembled 12 rooms west of the Marble Hall for his suite from 1802 to 1811, starting with an antechamber adjoining the Marble Hall.[lower-alpha 1]

Charlotte, Princess Royal of the United Kingdom and daughter of King George III, married Frederick, Elector, Duke and then King of Württemberg, 18 May 1797 at St James's Palace in Westminster.[24] In 1800, the peaceful atmosphere of the court in Stuttgart was disturbed by Napoleon Bonaparte marching an army into Württemberg, prompting the Duke and Duchess to flee to Vienna even as French soldiers entered the city.[25] The ducal couple was able to return to Württemberg and Frederick was given land and even made an Elector in the Holy Roman Empire and then a king in his own right by Napoleon in exchange for military support rendered to Napoleon.[25] George III, in a bout of his infamous mental illness, refused to recognize his daughter as Queen of Württemberg even when Frederick returned to the British fold in 1813,[24] nor when the couple's status as monarchs was confirmed at the Congress of Vienna in 1814.[25] When Frederick died three years later, Charlotte received many notable visitors from across Europe at Ludwigsburg Palace, among them some of her siblings.[26] The Dowager Queen died 5 October 1828 following a bout of illness[24] and she was interred in the Württemberg family vault.

When Duke Carl Alexander died suddenly at Ludwigsburg palace on 12 March 1737 as he was preparing to leave for a military inspection of the various fortresses in the duchy. The duke's equally unpopular Jewish minister of the economy, Joseph Suss Oppenheimer, was at Ludwigsburg palace having arrived by coach.[27]

In 1946, the trial of 15 of the 23 perpetrators of the Borkum Island Massacre took place in the palace.[28] The trials began 6 February and lasted until 22 March 1946.[29] Many of the defendants paid a heavy price for their role in the abuse and murder of seven American soldiers.

Music at Ludwigsburg

As the 18th century continued, the celebration of Duke Eberhard Louis's hunting order became was to become one of the most important festivities of court life, and serenatas and other performances would be held for these celebrations at Ludwigsburg Palace.[30] While no music or librettos from these performances remain, a document detailing accommodation for this event in 1715 sheds light on the parties involved.[31] Then senior concert master (German: Oberkapellmeister) Johann Christoph Pez would be lodged in the Old Hauptbau, with all of the musicians gathered in one large room, the Ducal comödianten divided into married members, housed in the orangery, and single members, housed at a nearby inn. These performances also likely involved two horn players, appointed and composed for by Pez in 1713.[32]

In 1918, following the close of the First World War, the palace was opened to the public. Four years later in 1922, the palace hosted its first musical performance since 1853: Händel's Rodelinda with guest performance by the Württemberg State Theatre as part of a meeting for the preservation of public heritage monuments. In 1931, Wilhelm Krämer founded the Ludwigsburger Mozartgemeinde, which then organized the Ludwigsburg Palace Concerts in 1932 that today continue to fill the rooms of the palace with music of all genres each summer.[33] From its beginning in the early 1930s to its final performed in 1939, numerous concerts[lower-alpha 2] were held in the Order Hall, Order Chapel, and the palace courtyard. Concerts and other festivities resumed two years after Second World War and in great number until, in 1980, Baden-Württemberg made the festival a state event and gave it a new name: the Ludwigsburg Festival.[34]

The Palace Theater, the oldest preserved palace theatre in Europe, was built during the reign of Duke Eberhard Louis but received its machinery in 1758, during the reign of Duke Charles Eugene. The single central axle underneath the stage, designed by Johann Christian Keim, allowed a single person to control the entire stage set, allowing for very speedy transitions that astounded visitors. The Theater had its first performance on 23 May 1758.[35]

Porcelain manufactory

Placeholder text

Burials in the Schlosskapelle

One of the 18 buildings of the residential palace is the Schlosskapelle (German: Castle chapel). The interior of the final resting place of several members of the House of Württemberg was decorated by Diego Carlone with his unique style of stucco sculpture.[36]

- Prince Frederick of Württemberg[37]

- Prince Paul of Württemberg

- Princess Charlotte of Saxe-Hildburghausen

- Catharina of Württemberg

- Eberhard Louis, Duke of Württemberg

- Johanna Elisabeth of Baden-Durlach

- Charles Alexander, Duke of Württemberg

- Princess Marie Auguste of Thurn and Taxis

- Charles Eugene, Duke of Württemberg

- Duchess Auguste of Württemberg

- Louis Eugene, Duke of Württemberg

- Duchess Sophia of Beichlingen

- Frederick II Eugene, Duke of Württemberg

- Margravine Friederike of Brandenburg-Schwedt

- King Frederick I of Württemberg

- Queen Charlotte Augusta Matilda[38]

- Pauline Therese of Württemberg

- Princess Maria Sophia of Thurn and Taxis

- Princess Florestine of Monaco

- Wilhelm, Duke of Urach

- Théodolinde de Beauharnais

- Wilhelm Karl, Duke of Urach

- Duchess Amalie in Bavaria

- Philipp Albrecht, Duke of Württemberg

Architecture

Ethos

Despite the efforts of some southern German architects,[lower-alpha 3] the spread of the Baroque style into the Holy Roman Empire had been halted in the mid-17th century by the ravages of the Thirty Years War. From the 1650s onward, the Baroque style bloomed in the Holy Roman Empire. The construction of the Palace of Versailles by French King Louis XIV that revolutionized palace construction in Europe. A new style of palace, a French one, came over Europe even as the political power of France diminished and was replaced with Austria. In Austria, an up-and-coming architect named Johann Bernhard Fischer von Erlach began the construction of Schönbrunn Palace in 1625, and his work blazed a trail for a new era of Versailles-inspired palaces across the Holy Roman Empire that many palaces, Ludwigsburg included, would follow in.[lower-alpha 4] Later German baroque architects such as Balthasar Neumann, Matthäus Daniel Pöppelmann, and Christoph Dientzenhofer set to work building new Baroque masterpieces throughout Germany such as the world-famous Würzburg Residence, which incorporated features of the preceding Austro-Italian as well as French Baroque styles into a masterful new palace.

Ludwigsburg Palace is built in a French Baroque model in the style of Versailles; like many other German princes, Eberhard Louis chose to abandon his traditional seat of power, in this case the aging Old Castle in Stuttgart for a grand baroque palace in the image of Versailles.[14] As was typical in Württemberg, the French influence on the palace is obvious, visible for example in the many mansard roofs of the palace.[21] However, while the model for the palace was, initially, Versailles, there are differences in the two palaces, such as the simple ornamentation of the Palace's windows,[40] which can be largely attributed to the Bohemian-trained hand of Donato Frisoni (who also hired a large staff largely composed of Italians).[18] The exterior were designed by Philipp Jenisch and Friedrich Nette, Germans, and the interior by Donato Frisoni, Diego and Carlo Carlone, Giuseppe Baroffio, Pietro Scotti and Luca Antonio Columba, Italians.[41] A result of this is that the palace bears much resemblance to late 17th century works in Prague and Vienna.[42] Of the three major undertakings of 18th century secular Swabian architecture,[lower-alpha 5] Ludwigsburg, the largest Baroque palace in Germany,[8] is the most important.[43]

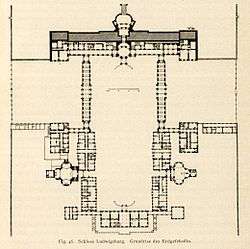

Design

The initial design by Philipp Jenisch was for a three-winged Baroque palace that included the Neues Herrschaftsgebäude, a preexisting structure that entered construction four years prior to Jenisch's design, as its unattached east wing, the corps de logis, and the north wing of the palace north wing would be attached to the Old corps de logis by an 11° angle made up by a staircase inspired by the palace at Rastatt. By the time he was replaced with Nette, the main building's ground floor and walls had been completed and much of the southern garden was terraced.[10]

In 1706 the young and talented court architect, Johann Friedrich Nette, had already created an elaborate design for a three-winged, U-shaped palace in the French Baroque style. In the following years a new wing, the future main building, began to be constructed to the north of the old corps de logis. Shortly thereafter, the main building was attached to the old hunting lodge with two narrow wings containing the hunting and play pavilions. One side wing has been attached orthogonally to the main building via the arcades, so that a three winged complex emerged with an honor court that opened to the south. Nette traveled twice to Prague in 1708 and 1709 to recruit experienced artisans and workers when construction of the interior began. By the time Nette died in 1715, his eight years on the site saw the completion of the north garden and much of the residential palace.[lower-alpha 6]

Among the experienced craftsmen Nette hired in Prague was an Italian stuccoist named Donato Giuseppe Frisoni who arrived at Ludwigsburg in 1709.[44] Already in 1709 had Duke Eberhard Louis entrusted the design of the city of Ludwigsburg to Frisoni. When Johann Friedrich Nette died in 1715, he became the lead architect working on the palace of Ludwigsburg against the will of the building commission.[18] His designs for the separation of the palace and the city as well as the equal prominence of the Protestant and Catholic churches in Ludwigsburg show progressive attitudes even as he continued the work Nette started before him at the palace.[13] However, Frisoni made the addition of the two chapels on either side of the palace. On the orders of Duke Eberhard Louis, Frisoni put into motion his plans for the final wing of the palace, the corps de logis on the southern edge of the courtyard. This new wing, large enough for the duke's ceremonies, was constructed from 1724 to 1733. The two side wings that connected the two corps de logis were fully under construction from 1726 to 1733.[11]

Interiors

The decoration and architectural design of Ludwigsburg Palace denote its function as a center of entertainment, an idea initially inherited from the Palace of Versailles. From there, however, there is an obvious departure from Versailles in the design and decor of Ludwigsburg Palace - its exteriors were designed by Germans (Philipp Jenisch, Friedrich Nette) and its interiors by Italians (Riccardo Retti, Andreas Quittainer, Donato Giuseppe Frisoni, Diego and Carlo Carlone, Giuseppe Baaroffio, Pietro Scotti, and Luca Antonio Columba), as opposed to the all-French contingent responsible for Versailles.[41] The distinctive features of the palace themselves are not French, but Italian, which can be observed in the elevation of the buildings of the palace, as seen in later 17th century works in Prague or Vienna. But it is in the interiors that we see a complete uniqueness from Versailles. Stylistically, the interiors are very Italian, decorated with stones and stucco. This is very noticeable, for instance, in the Mirror Gallery, where the stucco is matched with a suite of mirrors.[42]

Old Hauptbau

The Old Hauptbau, or Main building, was built to house the apartment of Duke Eberhard Louis to the west and his daughter-in-law, princess Henrietta Maria of Brandenburg-Schwedt, to the east. These apartments, following a 17th-century French Baroque model, have three rooms: a living room, an audience chamber, and the bedroom. However, The Ducal apartment was made unique by the addition of the Mirror Room. Decorated with stucco work by Donato Frisoni, it was expanded and joined with the ducal bedroom by the removal of the wall between these two spaces in 1721. Another expansion, hidden to the eye of viewers to the Ducal apartment, is the hidden stairway into the room of Eberhard Louis's mistress, Wilhelmine von Grävenitz.[45] Connected to the palace by narrow corridors of Nette's making are the Pleasure and Hunting pavilions to the east and west respectively. At the center of the Hunting pavilion (German: Jagdpavillon) is the marble hall and stucco works of Giacomo Antonio Corbellini, dubbed the Marmorsaletta,[46] that feature depictions of the Ducal hunting grounds, hunting horns, and the monogram of Duke Eberhard Louis.[47] The ceiling is dominated by the stucco and fresc work of Swiss artist Luca Antonio Colomba.[48] Attached are three rooms complete with stucco patterns mimicking Turkish carpets or imitations of Chinese paintings against black backgrounds, which were at that time popular with European rulers.[47] The Play pavilion (German: Speilpavillon), to the east, is comparatively less complex. Its central feature is a round marble hall with three large windows that gaze out into the surrounding gardens. Above this is a domed ceiling with stucco work by Diego Carlone and paintings, by Luca Antonio Colomba and Emanuel Wohlhaupter,[49] depicting the four seasons via the zodiac signs. The four corners of this pavilion are, in an example of Baroque exoticism, bizarre scenes painted in a style to imitate Delftware.[50] Below the roof added by Frisoni, there is a preserved piece of clockwork taken from Zwiefalten Abbey that was installed in the Old Hauptbau's attic on the orders of King Frederick I.[21]

East and West Wings

Beneath the Riesenbau are the barrel cellars that may predate the palace sitting above it. Past the vestibule of the cellars where a statue of Bacchus waits for and may sometimes spray water at visitors are the barrels that held the enormous quantities of wine consumed by the Ducal court, such as the Great Barrel that could dispense red or white wine as needed.[lower-alpha 7] Although much of it was consumed by the palace's residents, the wine was also an alternate form of payment for servant staff and part of the salary of officials at the palace.[51] Between the Riesenbau and the East Kavalierbau is the Schlosskapelle, or castle chapel, designed and constructed in 1716 by Donato Frisoni in a traditional Italian style. The chapel was built as a Protestant church, and was unique among them, but changed to being a Catholic church in the reign of Duke Charles Alexander and has remained Catholic since, albeit without the pulpit and organ, which were moved into the Ordensbau by King Frederick I.[17] Attached to the back of the Eastern Kavalierbau and to the Schlosskapelle is Europe's oldest preserved palace Theater, constructed for Duke Eberhard Louis from 1729 to 1733. Duke Charles Eugene, through court architect Philippe de la Guêpière, later added the theater's stage technology and auditorium interior and King Frederick I later tasked Friedrich von Thouret with the conversion to the Neoclassical interior as seen today in 1811.[35]

The Ordensbau, dates from the later half of the 1710s but today appears in a totally different style. The hall was first built to give Eberhard Louis more room for his hunting order, but under King Frederick it was remodeled according to his taste in the Neoclassical style. The Baroque stuccoes were stripped and replaced with columns and the massive fresco,[52] by Pietro Scotti and Giuseppe Baroffio,[42] painted over. In 1939, this painting was revealed once again. This hall, the largest room in the palace until the addition of the Marble Hall, served as Frederick's throne room and as the meeting hall for the Order of the Golden Eagle. Later, it was the site of the ratification of the constitutions of the Kingdom and then Free State of Württemberg in 1819 and 1919 respectively. Friedrich von Thouret also remodeled the attached Protestant chapel (German: Ordenskapelle) for use by the illustrious order of aristocrats that included the kings of Bavaria, Prussia, and Napoleon.[52]

New Hauptbau

The New Hauptbau is the largest and last wing of Ludwigsburg Palace, built for Duke Eberhard Louis on the southern edge of the courtyard and it contained the mansions of Eberhard Louis and his family. These rooms, connected by two staircases leading up to the suites on either side of the Marble Hall (German: Marmorsaal), were never completed in time for the Duke to enjoy them as he died in 1733. On the second floor of the New Hauptbau are the apartments Duke Charles Eugene, redesigned for his comfort by Philippe de La Guêpière in the Rococo style from 1757 to 1759 and decorated with stucco by Giovanni Pietro Brilli and Ludovico Bossi. King Frederick and his Queen, Charlotte Mathilde (the last ruler of Württemberg to reside at Ludwigsburg Palace), maintained their own suites in the New Hauptbau, and only three rooms in Charlotte's suite retained their Baroque interiors after the palace interiors were remodeled from 1816 and 1824.[23]

The roof above the Marble Hall, the primary feature of the New Hauptbau's corps de logis, is a feat of engineering in its own right. The great weight and oval plan of the Marble Hall meant that each section its roof had to be planned individually. The end result was a functional roof with no visible supports that was cantilevered upon the entablatures at the top the walls of the Marble Hall.[21]

Hidden in and around the extravagance of the palace are various secret corridors, halls, and even two courtyards hidden inside the New Hauptbau at its extreme edges for use by the palace's servant staff that have been preserved for viewing. Implemented by Frisoni, these secret attics, stairs, and hallways allowed servants to go about their duties without being seen while also allowing more light to enter into the palace and also providing some function as a drainage system.[20]

Grounds and gardens

Surrounding the palace on nearly all sides is the massive, 32 hectares (0.32 km2) Blooming Baroque garden, or in German, "Blühendes Barock." Although the history of the garden is as long as that of the palace it graces, the current incarnation of the garden was completed in 1954 for the palace's 250th birthday according to how it might have looked in 1800. This garden was only intended to last six months, but soon became a permanent fixture of the palace and is today looked after by the city of Ludwigsburg.[53] In today's garden, open from March to November, visitors will find many different designs and arrangements from various styles and cultures. Notable landmarks of this ever-changing garden are the Japanese and Sardinian gardens,[54] baroque Parterre, aviaries containing native as well as exotic birds in the northern garden, the "Valley of Birdsong," and the Emichsburg folly,[55] where tourists savvy in German can entice Rapunzel into lowering her hair.[56] The gardens, which annually host a large variety of events that can be easily charted via the calendar available on the Blooming Baroque's website (in German),[57] today brings more than 520,000 visitors annually.[58]

One entirely unique area of the gardens is the Fairy-Tale garden, German: Märchengarten, shown on the figure below, which contains some thirty depictions from several fairy tales including but not limited to the Rübezahl, Sindbad, Max and Moritz, The Frog Prince, Ali Baba, Sleeping Beauty, Aladdin, Rapunzel,[59] Pinocchio, Snow White, Hansel and Gretel, Little Red Riding Hood, and Rumpelstiltskin.[60]

When the first plans for a garden were laid, Duke Eberhard Louis favored creating a steep slope on the north side of the palace in the Italian style complete with terraces and water falls. However, when the castle began to expand, he turned his attention the south side of the palace and there laid out a symmetrical French baroque garden.[61] Duke Charles Eugene modified the gardens beginning 1750 in the South garden by removing some retaining walls and replacing them with an orangerie and a bosquet. However, 20 years later, the Duke began renting parts of the garden as his interest had left the gardens.[62] Then-Duke Frederick I ordered, in 1798, a redesign of the garden in a style more to his taste. The South garden was laid out simply, with a large canal with oval basin and four new compartments each with a vase by Antonio Isopi. In addition to the expansion of the gardens with the Eastern gardens, two private gardens were added specifically for the King and his wife, Queen Charlotte of England.[61][lower-alpha 8] The Emichsburg located in today's Fairy-tale garden was built in 1802 on a large rock in the area of an English garden located between Schloss Favorite and Monrepos and a park with carousels made for the amusement of guests to Ludwigsburg Palace.[61] The garden again fell out of favor in the reign of Frederick's son and successor, William I, who moved completely out of the palace for Rosenstein Palace in Stuttgart.[63] William I opened the garden to the public in 1828, planted an orchard on the southern parterre, filled in the basin and canal,[62] and began breeding Kashmir and Angora goats in Frederick's forest park.[64] After the dissolution of the Kingdom, the gardens largely became an orchard and potatoes were planted in the South garden and the palatial gardens remained in this state of disrepair for years.[63]

In 1947, Ludwigsburg's gardens were assigned to the care of Albert Schöchle, director of the State Agency of Plants and Gardens (German: Staatlichen Anlagen und Gärten).[65] The disrepair of the gardens was such that in the South garden, no path was visible and parts of the garden had become impassible on foot. While attending the Federal Garden Show of 1951 in Hanover, Schöchle became of the opinion that a superior garden show could be had at the sizable historical gardens of Ludwigsburg Palace. He was able to get his plans approved and construction underway by 23 March 1953, 13 months before the opening of the garden. Enormous amounts of earth had to be moved for the arrangement of the garden and laying of paths to begin and, by the autumn of 1953, much of the gardens had been laid out and hundreds of thousands of flowers planted.[63][66] On 23 April 1954,[66] the gardens finally opened to about 500,000 visitors by May of that year, among them Theodor Heuss. When the show ended a year later, not only was the event itself completely reimbursed by the proceeds, but the gardens could safely afford to become a permanent landmark of Ludwigsburg.[63] While on a business trip to Holland in 1957, Schöchle visited the fairy-tale garden near Tilburg, Holland, and was inspired. At the time, he was worried that without a new attraction, the Blooming Baroque gardens would again fail, but this time his superiors were not initially enthusiastic. After a period of convincing them of his vision, the design and construction of the new Fairy-tale garden, or Märchengarten, was opened to great acclaim.[67] Despite some stiff criticism, the success of the new park and garden astounded even Schöchle – by 1960, proceeds from the Fairy tale garden in 1961 were tenfold what they were when it opened the previous year.[68]

| Map of the palatial grounds | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||

| Figure: Map |

Schloss Favorite

This lustschloss and hunting lodge was built from 1713 to 1728 on commission from Duke Eberhard Louis, based on a garden in Vienna, to replace the hunting lodge Ludwigsburg originally was intended as and add more aesthetic value to the main palace grounds.[69] Like its parent palace, Schloss Favorite combines three styles (Baroque, Rococo, and Neoclassical). Originally, the palace's architect, Donato Giuseppe Frisoni, intended the palace to be surrounded by four circular pavilions and six alleys that would divide the palace grounds into a six-pointed star.[70] Though these plans never reached fruition, two of these avenues survive and they connect Schloss Favorite to Ludwigsburg Palace and Monrepos.[70] One baroque embellishment that survives to this day are the four pillars at the front entrance of the palace that symbolize the elements of earth, fire, water, and air.[70] Yet another interesting feature of Frisoni's palace is the flat roof terrace the Duke and honored guests could stand on and shoot at passing game from[71] that offers a decent view of the gardens around it. The downside of Schloss Favorite's flat roof was that construction and support for it was difficult to accomplish, and that water would quickly cause extensive damage.[72]

Schloss Favorite, designed by Donato Giuseppe Frisoni, was not intended for long stays,[64][69] but it was perfectly outfitted for the more glamorous functions of court, especially balls.[70] Schloss Favorite was used as the backdrop to a firework display for his wedding to Elisabeth Frederika Sophie in 1748.[73] This would not be the first time Charles Eugene would alter the palace's function for the palace for his wife. For Fredericka's eighteenth birthday, the Duke had the palace transformed into an opera house for a showing of Carl Heinrich Graun's Artaserse – the premiere of which he had been a guest to in 1743 in Berlin.[74]

The interiors of the palace were converted to the Neoclassical style in 1800 by court architect Nikolaus Friedrich von Thouret on the orders of then King Frederick because the baroque interiors of the palace were by then passé and not of his taste.[70] Three years prior, in 1797, Frederick I had von Thouret redesign the main hall, called the Festaal, and neighboring rooms in the Neoclassical style.[75] Today, only one room, in the western half of the building, retains its original baroque appearance.[76] In the 20th century, the palace fell into disrepair but it was renovated in the 1980s. Since 1983, Schloss Favorite has been open to the public all days of the week except Monday. In 2017, the palace was closed all year for renovations.[77]

Monrepos

Along one of the two surviving roads from Frisoni's designs for Schloss Favorite, Charles Eugene, Duke of Württemberg, decided to erect a new Rococo-Empire style palace on the site of a pavilion Eberhard Louis had built in 1714. So it was that Duke Charles transformed the area around Schloss Favorite and started construction of Schloss Monrepos on the north shore of Lake Eglosheimer so that he could climb into Venetian gondolas from the palace and enjoy the lake. Construction would last from 1764 to 1768 and cost the Duchy of Württemberg a sum of at least 300,000 florins.[2] Unfortunately for Duke Charles, the architect he charged with the construction of his new palace, Philippe de La Guêpière, could not overcome the dampening of his construction material. Once again, it was the interest of the first King of Württemberg, Frederick I, that would save the palace. In his reign, the simple solution of lowering the water level of the lake to make construction possible was discovered, allowing the palace could be completed.[64] Frederick also had the palace redecorated in the Neoclassical style and today it hosts an annual summer firework display as part of the Ludwigsburg Palace Festival.[78]

Tourism

From opening time at 10 AM to 5 PM CET, a 90-minute-long guided tour in German begins every half-hour. A tour in English is offered at 1:30 PM.[56]

Ludwigsburg Palace is home to an annual Venetian fair that has its origins in enchantment of Duke Charles Eugene with Venice following a trip there in 1768. Reintroduced in 1993, the fair offers visitors a glimpse of Venice either on the grounds of the palace, in the procession through the city, or in the gondolas. A market for hand crafted good such as masks, beads, jewelry, and Murano glass is part of the festivities.[79]

Museums

The Baroque Gallery (German: Barockgalerie) on the second floor of the Old Hauptbau is a branch of the Staatsgalerie Stuttgart,[80] opened in 2004 for the 300th anniversary of the palace's construction,[81] that houses historical works by numerous German and Italian artists such as Johann Heinrich Schönfeld.[82] Inside the 680 square metres (7,300 sq ft) space occupied by the museum,[81] visitors can see over 120 paintings in the collection of the Stuttgart Staatsgalerie that includes a portrait of Prussian ambassador to Vienna, Gustav Adolf Graf von Gotter,[lower-alpha 9] by Viennese court painter Martin van Meytens,[80] by Memminger Johann Heiss, Carl Andreas Ruthart, and even some works formerly belonging to Cosimo III, Duke of Tuscany.[83]

There are two museums at Ludwigsburg, both were also opened in 2004, that are part of the larger Landesmuseum Württemberg. The first is the Ceramics museum (German: Keramiksmuseum) that occupies a 2,000 square metres (22,000 sq ft) space on the second floor of the southern wing with a large collection of some 4500 individual exhibits of porcelains and ceramics, making it the second largest such collection in Germany.[84] It displays majolica, faience, pottery, and the histories thereof from the Middle Ages to the present day. The main focus of the museum is European porcelain of the 18th and 19th centuries, and the museum features pieces made in the major porcelain manufacturies such as those in Meissen and Vienna. Though the Ludwigsburg manufacturer was an initiative begun by Duke Charles Eugene to compete with other European courts, the current collection has its origins in 1950.[85] Of the museum's large collection, some 800 pieces of rare and colorful Italian maiolica from the personal collection of Charles Eugene are on display in their own exhibit in the museum.[84] The other is the Fashion museum (German: Modemuseum) that displays about 700 various pieces of fashion and accessories from the rococo period to the second half of the 20th century. The museum is inside of the Festinbau and features works by Worth, Poiret, Dior, and Miyake,[86] as well as a silk nightgown that belonged to the Margrave of Baden. Multiple multi-lingual audio guides and screens at each exhibit complete with annotated accompanying video are available for use by visitors to this museum.[87]

Ludwigsburg maintains a lapidarium that houses statuary from the palace's past for their preservation on the ground floor of the New Hauptbau in the former Silver Room. The sandstone statues in the collection, depictions of mythological creatures, heroes, kings, and pagan deities typical to the Baroque period, had been adversely affected by over two centuries of erosion by the weather had have been replaced. The originals, still preserved and presented today, are by Andreas Philipp Quittainer, Carlo and Giorgio Feretti, Christian Friedrich Wilhelm Beyer and Pierre François Lejeune.[88] On the second floor of the New Hauptbau is the Princess Olga Cabinet Exhibition, exploring the life and times of the royal family of Württemberg in the 20th century though historical photographs taken inside the palace.[89]

For children aged four and beyond, there is an interactive museum called Kinderreich, that aims to teach children about life in the court of the Duke of Württemberg via hands-on methods that include the wearing of period dress. Children are led through the exhibit by Frederico, the "Royal Palace Eagle," through the dressing room with its many garments and accessories to a mock courtroom that hosts several stations that educate children on an aspect of court life at Ludwigsburg.[90][91] The Young Stage (German: Junge Bühne) is yet another facet of Kinderreich wherein children learn about Baroque stage performance.[92]

In the Palace Theater are about 140 preserved original set pieces and props from the 18th and 19th centuries discovered during restoration work on the Theater, such as oil lamps used for stage lighting. These items were extensively restored to their original condition from 1987 until 1995 and, since 1995, one of the original stage pieces has been used for the Children's Stage (German: Junge Bühne). The Theater Museum also allows visitors to use reconstructed noise props used during Baroque plays to recreate the sound of thunder, wind, and rain.[19]

In popular culture

_-_panoramio.jpg)

- Some scenes of Stanley Kubrick's Barry Lyndon were filmed in the palace.[93]

See also

Notes

Footnotes

- ↑ The six rooms, all remodeled in the Neoclassical style, for official function of Frederick's suite are in the southern part of the building and look out across the southern garden, whereas the private rooms look north, into the courtyard.[23]

- ↑ The Ludwigsburg Festival's website notes six to ten concerts.[34]

- ↑ Such architects as Elias Holl and a few theorists including but not limited to Joseph Furttenbach the Elder.

- ↑ A Global History of Architecture lists Schönbrunn Palace, Branicki Palace in Białystok, Zwinger Palace in Dresden, Ludwigsburg Palace, the Augustusburg, The Belvedere, Torre Tagle Palace, Winter Palace, Amalienborg Palace, Stockholm Palace, and the Palace of Orodea as "Post-Versailles Baroque Buildings."[39]

- ↑ Those three, according to Volume VI of the Encyclopedia of World Arts, are Ludwigsburg and the palaces at Rastatt and Karlsruhe.[43]

- ↑ An engraving made by Nette while on a trip to Augsburg shows his designs for the three-winged palace and much of the northern garden that he had largely completed by 1714.[12]

- ↑ This barrel, which required the wood of ten oak trees for its construction, was built on the orders of Duke Eberhard Louis and for 30 years was the largest barrel in Germany. It held 90,000 liters of wine.[51]

- ↑ Allegedly, Frederick designed this garden himself. An artist's rendition of this garden is available for viewing at the top of the History page on the Blooming Baroque's website.[62]

- ↑ In German, "Graf" is an honorific title that denotes a Count.

Citations

- 1 2 Dorling 2001, p. 292.

- 1 2 Wilson 1995, p. 36.

- ↑ "Ludwigsburg palace". stuttgart-tourist.de/en. Region Stuttgart.

- 1 2 Charles & Carl 2010, p. 141.

- 1 2 3 Rough Guide 2015.

- 1 2 3 Kaufmann 1995, p. 320.

- ↑ Owens 2011, p. 166.

- 1 2 Kerner 2015, p. xx.

- ↑ Kaufmann 1995, pp. 320-21.

- 1 2 3 Bieri, Pius. "Philipp Joseph Jenisch". sueddeutscher-barock.ch (in German). Süddeutscher Barock.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Die Gebäude". schloss-ludwigsburg.de (in German). Staatliche Schlösser und Gärten.

- 1 2 3 Bieri, Pius. "Johann Friedrich Nette". sueddeutscher-barock.ch (in German). Süddeutscher Barock.

- 1 2 Placzek2 1982, p. 118.

- 1 2 Owens 2011, p. 175.

- 1 2 "History of Ludwigsburg". ludwigsburg.de/. City of Ludwigsburg.

- 1 2 3 "Ideal city". ludwigsburgmuseum.de. City of Ludwigsburg.

- 1 2 "Die Schlosskapelle". schloss-ludwigsburg.de/ (in German). Staatliche Schlösser und Gärten.

- 1 2 3 4 "Donato Giuseppe Frisoni". schloss-ludwigsburg.de (in German). Staatliche Schlösser und Gärten.

- 1 2 "Das Schlosstheater". schloss-ludwigsburg.de (in German). Staatliche Schlösser und Gärten.

- 1 2 "Die Dienerschaftszimmer". schloss-ludwigsburg.de (in German). Staatliche Schlösser und Gärten.

- 1 2 3 4 "Die Dächer". schloss-ludwigsburg.de (in German). Staatliche Schlösser und Gärten.

- ↑ "Good prince". ludwigsburgmuseum.de. City of Ludwigsburg.

- 1 2 "Der Neue Hauptbau". schloss-ludwigsburg.de (in German). Staatliche Schlösser und Gärten.

- 1 2 3 Panton 2011, p. 103.

- 1 2 3 Curzon 2016, p. 70.

- ↑ Curzon 2016, pp. 70-1.

- ↑ Tegel 2011, p. 29.

- ↑ Weingartner 2011, p. 49.

- ↑ Sliedregt 2012, p. 183.

- ↑ Owens 2011, p. 170.

- ↑ Owens 2011, pp. 170-71.

- ↑ Owens 2011, p. 171.

- ↑ "Ludwigsburger Schlossfestspiele". ludwigsburg.de (in German). City of Ludwigsburg.

- 1 2 "Chronicle". schlessfestspiele.de/en. Ludwigsburg Festival.

- 1 2 "The Palace Theatre". schloss-ludwigsburg.de/en. Staatliche Schlösser und Gärten.

- ↑ Placzek1 1982, p. 381.

- ↑ Lorenz, Mertens & Press 1997.

- ↑ Weir 2011, p. 288.

- ↑ Jarzombek & Prakash 2011.

- ↑ MyersXII, p. 265.

- 1 2 Kaufmann 1995, p. 321.

- 1 2 3 Kaufmann 1995, p. 322.

- 1 2 MyersVI, p. 189.

- ↑ Baumgart, Fritz. "Frisoni, Donato Giuseppe". treccani.it (in Italian). Enciclopedia Italiana.

- ↑ "Der Alte Hauptbau". schloss-ludwigsburg.de (in German). Staatliche Schlösser und Gärten.

- ↑ "CORBELLINI, Giacomo Antonio". treccani.it (in Italian). Enciclopedia Italiana.

- 1 2 "Der Jagdpavillon". schloss-ludwigsburg.de (in German). Staatliche Schlösser und Gärten.

- ↑ "COLOMBO, Luca Antonio". treccani.it (in Italian). Enciclopedia Italiana.

- ↑ "Wohlhaupter, Emanuel Johann K.". altemeister.museum-kassel.de.

- ↑ "Der Spielpavillon". schloss-ludwigsburg.de (in German). Staatliche Schlösser und Gärten.

- 1 2 "Der Fasskeller". schloss-ludwigsburg.de (in German). Staatliche Schlösser und Gärten.

- 1 2 "Order Building and Order Chapel". schloss-ludwigsburg.de/en. Staatliche Schlösser und Gärten.

- ↑ "Entdecken Sie das Blühende Barock". blueba.de (in German). City of Ludwigsburg.

- ↑ "The Garden Show Blooming Baroque and the Fairy-Tale Garden". ludwigsburg.de. City of Ludwigsburg.

- ↑ "Blühendes Barock Ludwigsburg (Baroque in Bloom)". stuttgart-tourist.de/en. Region Stuttgart.

- 1 2 Christiani 2015, p. 317.

- ↑ "Im Blühenden Barock ist immer was los". blueba.de (in German). City of Ludwigsburg.

- ↑ "Besuchen Sie das Blühende Barock und den Märchengarten". blueba.de (in German). City of Ludwigsburg.

- ↑ "Der Märchengarten im Blühenden Barock". blueba.de (in German). City of Ludwigsburg.

- ↑ "Rundgang Märchen". blueba.de (in German). City of Ludwigsburg.

- 1 2 3 "Der Garten". schloss-ludwigsburg.de (in German). Staatliche Schlösser und Gärten.

- 1 2 3 "Die Geschichte der Ludwigsburger Schlossgärten". blueba.de (in German). City of Ludwigsburg.

- 1 2 3 4 "Albert Schöchle hatte die Idee zum Blühenden Barock". blueba.de. City of Ludwigsburg.

- 1 2 3 "Der Garten". schloss-favorite-ludwigsburg.de (in German). Staatliche Schlösser und Gärten.

- ↑ "Albert Schöchle - Vater des Blühenden Barock". blueba.de. City of Ludwigsburg.

- 1 2 "Albert Schöchle hatte es geschafft". blueba.de. City of Ludwigsburg.

- ↑ "Wie Albert Schöchle die Idee zum Märchengarten hatte". blueba.de (in German). City of Ludwigsburg.

- ↑ "Albert Schöchle hatte es wieder einmal geschafft!". blueba.de (in German). City of Ludwigsburg.

- 1 2 "Das Schloss und der Garten". schloss-favorite-ludwigsburg.de (in German). Staatliche Schlösser und Gärten.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Das Gebäude". schloss-favorite-ludwigsburg.de (in German). Staatliche Schlösser und Gärten.

- ↑ Wilson 1995, p. 127.

- ↑ "Die Dachterrasse". schloss-favorite-ludwigsburg.de (in German). Staatliche Schlösser und Gärten.

- ↑ "Elisabeth Friederike Sophie von Brandenburg-Bayreuth". schloss-favorite-ludwigsburg.de (in German). Staatliche Schlösser und Gärten.

- ↑ Heartz 2003, p. 445.

- ↑ "Der Festsaal". schloss-favorite-ludwigsburg.de (in German). Staatliche Schlösser und Gärten.

- ↑ "Die westlichen Zimmer". schloss-favorite-ludwigsburg.de (in German). Staatliche Schlösser und Gärten.

- ↑ "Besucherinformation Schloss Favorite Ludwigsburg". schloss-favorite-ludwigsburg.de (in German). Staatliche Schlösser und Gärten.

- ↑ "Seeschloss Monrepos". stuttgart-tourist.com. Region Stuttgart.

- ↑ "Venetian Fair Ludwigsburg". ludwigsburg.de. City of Ludwigsburg.

- 1 2 "Die Barockgalerie". schloss-ludwigsburg.de (in German). Staatliche Schlösser und Gärten.

- 1 2 Bühler, Dr. Christoph. "Barockgalerie in Schloss Ludwigsburg". zum.de. Landeskunde online.

- ↑ "Johann Heinrich Schönfeld". staatsgalerie.de/en (in German). Stuttgart State Gallery. Retrieved 3 July 2010.

- ↑ Bühler, Dr. Christoph. "Barockgalerie in Schloss Ludwigsburg". zum.de. Landeskunde online.

- 1 2 "Das Keramikmuseum". schloss-ludwigsburg.de (in German). Staatliche Schlösser und Gärten.

- ↑ "Keramiksmuseum". landesmuseum-stuttgart.de (in German). Landesmuseum Württemberg.

- ↑ "Das Modemuseum". schloss-ludwigsburg.de (in German). Staatliche Schlösser und Gärten.

- ↑ "Modemuseum". landesmuseum-stuttgart.de (in German). Landesmuseum Württemberg.

- ↑ "Das Lapidarium". schloss-ludwigsburg (in German). Staatliche Schlösser und Gärten.

- ↑ "Die Kabinettausstellung Prinzession Olga". schloss-ludwigsburg.dde (in German). Staatliche Schlösser und Gärten.

- ↑ "Kinderreich Schloss Ludwigsburg". ludwigsburg.de (in German). City of Ludwigsburg.

- ↑ "Das Kinderreich". schloss-ludwigsburg.de (in German). Staatliche Schlösser und Gärten.

- ↑ "Junge Bühne". ludwigsburg.de (in German). City of Ludwigsburg.

- ↑ "Und ewig locken die barocken Kulissen - Stuttgarter Zeitung" (in German). Retrieved 2016-06-26.

References

- Charles, Victoria; Carl, Klaus H. (2010). Rococo. Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam: Baseline Co. Ltd. ISBN 978-1-84484-740-2.

- Curzon, Catherine (31 August 2016). Life in the Georgian Court. Pen and Sword. ISBN 1473845548.

- Dorling Kindersley (6 August 2001). Eyewitness Travel Guide to Germany. Eyewitness Travel Guide. New York City: Dorling Kindersley Publishing. ISBN 0-7894-6646-5.

- Heartz, Daniel (2003). Music in European Capitals: The Galant Style, 1720-1780. New York City: W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 0393050807.

- Jarzombek, Mark M.; Prakash, Vikramaditya (4 October 2011). A Global History of Architecture. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 0470902485.

- Kaufmann, Thomas DaCosta (1995). Court, Cloister, and City: The Art and Culture of Central Europe, 1450-1800. Chicago, USA: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-42729-3.

- Kerner, Justinus (18 April 2015). Segel, Harold B., ed. Sketches from My Boyhood by Justinus Kerner. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Scholars Publishing. ISBN 1443883344.

- Lorenz, Sönke; Mertens, Dieter; Press, Volker (1997). Das Haus Württemberg: ein biographisches Lexikon. Stuttgart, Germany: Kohlhammer. ISBN 3-17-013605-4.

- Myers, Bernard S. (1959). Encyclopedia of World Art. VI Games and Toys — Greece. New York City, United States (NY): McGraw-Hill Publishers. ISBN 0070194661.

- Myers, Bernard S. (1959). Encyclopedia of World Art. X Middle American Protohistory — Painting. New York City: McGraw-Hill Publishers. ISBN 0070194661.

- Myers, Bernard S. (1959). Encyclopedia of World Art. XII Renaissance — Shaun. New York City: McGraw-Hill Publishers. ISBN 0070194661.

- Owens, Samantha; Reul, Barbara M.; Stockigt, Janice B., eds. (2011). "The Court of Württemberg-Stuttgart". Music at German Courts, 1715–1760: Changing Artistic Priorities. Forward by Michael Talbot. Suffolk, UK: Boydell Press. ISBN 978-1-84383-598-1.

- Panton, James (24 February 2011). Historical Dictionary of the British Moanrchy. Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press. ISBN 0810874970.

- Placzek, Adolf K., ed. (1982). Macmillian Encyclopedia of Architects. 1 Aalto to Duthoit. New York City: Free Press. ISBN 0-02-925010-2.

- Placzek, Adolf K., ed. (1982). Macmillian Encyclopedia of Architects. 2 Eads to Lewis. New York City: Free Press. ISBN 0-02-925020-X.

- Rough Guides (14 April 2015). Rough Guide to Germany. London, UK: Penguin Random House. ISBN 0241214076.

- Schulte-Peevers, Andrea; Christiani, Kerry; Di Duca, Marc; Le Nevez, Catherine (15 March 2016). "Stuttgart and the Black Forest". Germany. Melbourne, Australia: Lonely Planet. ISBN 978-1-74321-023-9.

- Sliedregt, Elies (2012). Individual Criminal Responsibility in International Law. Oxford Press. ISBN 978-0-19-956036-3. Retrieved 23 September 2014.

- Tegel, Susan (9 June 2011). Jew Suss: Life, Legend, Fiction, Film. London, UK: Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 1441162976.

- Wilson, Peter H. (23 March 1995). War, State, and Society in Württemberg, 1677–1793. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 052148331X.

- Weingartner, James J. (2011). Americans, Germans and War Crimes Justice: Law, Memory and "the Good War". Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 0313381925.

- Weir, Alison (18 April 2011). Britain's Royal Families: The Complete Genealogy. New York City: Random House. ISBN 1446449114.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Residenzschloss Ludwigsburg. |

- (in English) & (in German) Ludwigsburg Palace (State Home and Garden Authority Baden-Württemberg)

- (in English) & (in German) Ludwigsburg Palace Festival

- (in English) & (in German) Ludwigsburg Venetian Fair

- (in German) Residenzschloss Ludwigsburg (Landeskunde Online)

- (in German) Ludwigsburg (burgen-web.de)

- (in German) Schloss Ludwigsburg (Schlösser und Burgen in Baden-Württemberg)