Schillinger v. United States

| Schillinger v. United States | |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Argued October 9–10, 1894 Decided November 19, 1894 | |

| Full case name | Schillinger v. United States |

| Citations | |

| Prior history | Appeal from the United States Court of Claims |

| Holding | |

| The government of the United States may not be sued in Federal Court without its consent | |

| Court membership | |

| |

| Case opinions | |

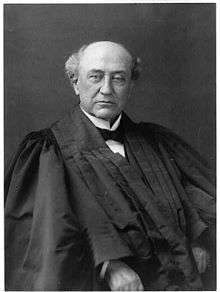

| Majority | Brewer, joined by Field, Gray, Brown, Jackson, White, Fuller |

| Dissent | Harlan, joined by Shiras |

| Laws applied | |

| Tucker Act | |

Schillinger v. United States, 155 U.S. 163 (1894), is a decision of the United States Supreme Court, holding (7–2, per Justice Brewer) that a suit for patent infringement cannot be entertained against the United States, because patent infringement is a tort and the United States has not waived sovereign immunity for intentional torts.[1][2]

Background

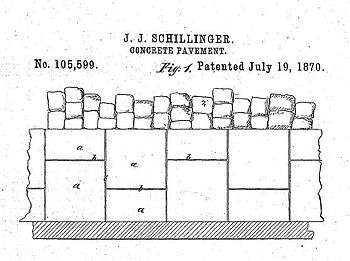

A patent issued to John J. Schillinger for an improvement in concrete pavement. Later, the Architect of the Capitol invited proposals for a concrete pavement in the capitol grounds, and entered into a contract for the laying of such pavement according to plans and specifications prepared by the Architect, which did not refer specifically to the patent.

Schillinger then sued under the patent to recover damages from the United States for the wrongful use of the invention in the construction of the pavement. The Court of Claims held that there was no contract, either expressed or implied, on the part of the government for the use of such patent, and dismissed the petition as outside of the jurisdiction of the court.

Opinion of the Court

Justice Brewer wrote the majority opinion. Justice Harlan, joined by Justice Shiras, dissented.

The doctrine of sovereign immunity provides that the United States cannot be sued without its consent. When Congress consents to suits against the government, it has "an absolute discretion to specify the cases and contingencies in which the liability of the government is submitted to the courts for judicial determination." The courts may not "go beyond the letter of such consent," no matter how beneficial they may deem it to do so, for only Congress has that power.

Until the creation of the Court of Claims in 1855, the only recourse of claimants that the United States had wronged them was to appeal to Congress. The jurisdictional statute for the court defined the claims that could be submitted to the Court of Claims as follows:

The Court of Claims shall have jurisdiction to hear and determine all claims founded upon the Constitution of the United States or any law of Congress …or upon any contract, expressed or implied, with the Government of the United States, or for damages …in cases not sounding in tort, in respect of which claims the party would be entitled to redress against the United States … if the United States were suable.

The Court of Claims thus has no jurisdiction over claims against the government for mere torts. To be sure, the Constitution forbids the taking of private property for public uses without just compensation. But that does not create a claim founded upon the Constitution of the United States and within the jurisdictional grant of the Court of Claims. Congress never intended that every wrongful seizure of property by an officer of the government, the Court explained, would expose the government to an action for damages in the Court of Claims, for the statute expressly excludes tort actions and that exclusion would be meaningless under the foregoing broad reading.

That Schillinger's action was one sounding in tort is clear, the Court said, for the petition charges a wrongful appropriation by the government, against the protest of the claimants, and prays to recover the damages done by the wrong. There is no express or implied contract—no statement tending to show a "coming together of minds" in respect to anything. The Court therefore concluded:

Do the facts, as stated in the petition or as found by the court, show anything more than a wrong done, and can this be adjudged other than a case "sounding in tort"? We think not, and therefore the judgment of the Court of Claims is affirmed.

Subsequent developments

Congress subsequently passed 28 U.S.C. § 1498, which permits owners of intellectual property rights such as patents, copyrights, and mask works to sue for "just and entire compensation" when the United States uses such intellectual property rights.

The United States Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit recently held that no action against the United States lies for patent-related cases not fitting squarely within the language of § 1498, because sovereign immunity has not been waived for intentional torts[3] and, consistent with Schillinger, patent infringement is not a taking of property under the Fifth Amendment.[4] The Federal Circuit held that patent rights are not property interests under the Fifth Amendment, reasoning that § 1498's "new and limited waiver of sovereign immunity" would have been unnecessary if Congress intended for patents to be compensable rights under the Takings Clause. The Federal Circuit so ruled despite a number of obiter dicta in previous decisions that assumed that patent infringement was a taking of property. The Federal Circuit's ruling is consistent with current Supreme Court takings jurisprudence, however, because patent infringement does not usually deprive the patentee of substantially all of the value of the patent.[5]

References

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- ↑ Durchslag, Melvyn R. "State Sovereign Immunity: A Reference Guide to the United States Constitution", via Google Books, p. 133, Greenwood Publishing Group, 2002. ISBN 0-313-31348-2. Accessed January 20, 2009.

- ↑ The United States subsequently waived sovereign immunity for torts committed negligently.

- ↑ See 28 U.S.C.A. § 2680 (permitting suit for some intentional torts but not most others).

- ↑ Zoltek v. United States, 442 F.3d 1345 (Fed. Cir. 2006). The Supreme Court denied certiorari.

- ↑ See FindLaw Penn Central Transportation Co. v. City of New York, 438 U.S. 104 (1978) (no taking because NYC's action did not deprive Penn Central of substantially all of the value of Grand Central Station).