Sichuan pepper

| Sichuan pepper | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese | 花椒 | ||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Literal meaning | "flower pepper" | ||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||

Sichuan pepper, Sichuan peppercorn, or Chinese coriander, is a commonly used spice in Chinese, Tibetan, Nepali, and Indian cuisine. It is derived from at least two species of the global genus Zanthoxylum, including Z. simulans and Z. bungeanum. The genus Zanthoxylum belongs in the rue or citrus family, and, despite its name, is not closely related to either black pepper or the chili pepper.

The husk or hull (pericarp) around the seeds may be used whole, especially in Sichuan cuisine or Szechwan cuisine or Szechuan cuisine, and the finely ground powder is one of the ingredients for five-spice powder. It is also used in traditional Chinese medicine. The pericarp is most often used, but the leaves of various species are also used in some regions of China.[1]

Another species of Zanthoxylum native to China, Z. schinifolium, called 香椒子 (xiāng jiāo zi, "aromatic peppercorn") or 青花椒 (qīng huā jiāo, "green flower pepper"), is used as a spice in Hebei.[1]

While the exact flavour and composition of different species from the Zanthoxylum genus vary, most share the same essential characteristics. So while the terms "Sichuan pepper" and sanshō may refer specifically to Z. simulans and Z. piperitum, respectively, the two are commonly used interchangeably.[2]

Related species are used in the cuisines of Tibet, Bhutan, Nepal, Thailand, and the Konkani and Toba Batak peoples. In Bhutan, this pepper is known as thingye and is used liberally in preparation of soups, gruels, and phaag sha paa (pork slices). In Nepal, timur is used in the popular foods momo, thukpa, chow mein, chicken chilli, and other meat dishes. It is also widely used in homemade pickles. People take timur as a medicine for stomach or digestion problems, in a preparation with cloves of garlic and mountain salt with warm water.

Names

Sichuan pepper is known in Chinese as huā jiāo. A lesser-used name is shān jiāo (山 椒, not to be confused with Tasmanian mountain pepper, which is also the root of the Japanese sanshō (山椒). Confusingly, the Korean sancho (산초, 山椒) refers to a different if related species (Z. schinifolium), while Z. piperitum is known as chopi (초피).[4]

The name hua jiao in a strict sense refers to the northern China peppercorn, Z. bungeanum, according to the common consensus in current scholarly literature.[5][6][7] However, hua jiao is also the generic term in commerce for all such viable spices harvested from the genus. This includes Z. simulans (Hance), identified by a taxonomical authorities as the yě huā jiāo (野花椒, "wild peppercorn"),[5][8] though elsewhere given as chuān jiāo (川椒, "Sichuan pepper"[9]), leading to the tendency to regard this as the bona fide "Sichuan pepper".

The Indian subcontinent uses a number of varieties of Sichuan pepper. In Konkani, it is known as tephal or tirphal.[10] In Nepali, Z. alatum is known as timur (टिमुर)or timbur, while in Tibetan, it is known as yer ma (གཡེར་མ)[4] and in Bhutan as thingye. It is also called current mirchi commonly.

In Indonesia's North Sumatra province, around Lake Toba, Z. acanthopodium is known as andaliman in the Batak Toba language[4] and tuba in the Batak Karo language.

In America, names such as "Szechwan pepper", "Chinese pepper", "Japanese pepper", "aniseed pepper", "sprice pepper", "Chinese prickly-ash", "fagara," "sansho", "Nepal pepper", "Indonesian lemon pepper", and others are used, sometimes referring to specific species within this group, since this plant is not well known enough in the West to have an established name. Some brands also use the English description "dehydrated prickly ash" since Sichuan pepper, and Japanese sansho, are from related plants that are sometimes called prickly ash because of their thorns (though purveyors in the US do sell native prickly ash species (Z. americanum) because it is recognized as a folk remedy[11]). In Kachin State of Myanmar, the Jinghpaw people widely use it in traditional cuisine. It is known as ma chyang among them. Its leaves are served as one of ingredients in cooking soups.

Culinary uses

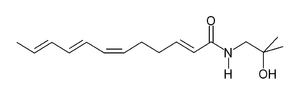

Sichuan pepper's unique aroma and flavour is not hot or pungent like black, white, or chili peppers. Instead, it has slight lemony overtones and creates a tingly numbness in the mouth (caused by its 3% of hydroxy alpha sanshool) that sets the stage for hot spices. According to Harold McGee in On Food and Cooking, they are not simply pungent; "they produce a strange, tingling, buzzing, numbing sensation that is something like the effect of carbonated drinks or of a mild electric current (touching the terminals of a nine-volt battery to the tongue). Sanshools appear to act on several different kinds of nerve endings at once, induce sensitivity to touch and cold in nerves that are ordinarily nonsensitive, and so perhaps cause a kind of general neurological confusion."[12]

Recipes often suggest lightly toasting the tiny seed pods, then crushing them before adding them to food. Only the husks are used; the shiny black seeds are discarded or ignored as they have a very gritty, sand-like texture. The spice is generally added at the last moment. Star anise and ginger are often used with it in spicy Sichuan cuisine. It has an alkaline pH and a numbing effect on the lips when eaten in larger doses. Ma la sauce (Chinese: 麻辣; pinyin: málà; literally "numbing and spicy"), common in Sichuan cooking, is a combination of Sichuan pepper and chili pepper, and it is a key ingredient in má là hot pot, the Sichuan version of the traditional Chinese dish. It is also a common flavouring in Sichuan baked goods such as sweetened cakes and biscuits. Beijing microbrewery Great Leap Brewing uses Sichuan peppercorns, offset by honey, as a flavouring adjunct in its Honey Ma Blonde.[13]

Sichuan pepper is also available as an oil (Chinese: 花椒油, marketed as either "Sichuan pepper oil", "Bunge prickly ash oil", or "huajiao oil"). In this form, it is best used in stir-fry noodle dishes without hot spices. The recipe may include ginger oil and brown sugar cooked with a base of noodles and vegetables, then adding rice vinegar and Sichuan pepper oil after cooking.

Hua jiao yan (simplified Chinese: 花椒盐; traditional Chinese: 花椒鹽; pinyin: huājiāoyán) is a mixture of salt and Sichuan pepper, toasted and browned in a wok, and served as a condiment to accompany chicken, duck, and pork dishes. The peppercorns can also be lightly fried to make a spicy oil with various uses.

In Indonesian Batak cuisine, andaliman (a relative of Sichuan pepper, Z. acanthopodium) is ground and mixed with chilies and seasonings into a green sambal tinombur or chili paste, to accompany grilled pork, carp, and other regional specialties. Arsik, a Batak dish from the Tapanuli region, uses andaliman as spice.

Sichuan pepper is one of the few spices important for Nepali, Tibetan, and Bhutanese cookery of the Himalayas because few spices can be grown there. One Himalayan specialty is the momo, a dumpling stuffed with vegetables, cottage cheese, or minced yak meat, water buffalo meat, or pork and flavoured with Sichuan pepper, garlic, ginger, and onion, served with tomato and Sichuan pepper-based gravy. Nepalese-style noodles are steamed and served dry, together with a fiery Sichuan pepper sauce.

In Korean cuisine, two species are used: Z. piperitum and Z. schinifolium.[4]

Phytochemistry

Important aromatic compounds of various Zanthoxylum species include:

- Zanthoxylum fagara (Central & Southern Africa, South America) — alkaloids, coumarins (Phytochemistry, 27, 3933, 1988)

- Zanthoxylum simulans (Taiwan) — Mostly beta-myrcene, limonene, 1,8-cineole, Z-beta-ocimene (J. Agri. & Food Chem., 44, 1096, 1996)

- Zanthoxylum armatum (Nepal) — linalool (50%), limonene, methyl cinnamate, cineole

- Zanthoxylum rhetsa (India) — Sabinene, limonene, pinenes, para-cymene, terpinenes, 4-terpineol, alpha-terpineol. (Zeitschrift f. Lebensmitteluntersuchung und -forschung A, 206, 228, 1998)

- Zanthoxylum piperitum (Japan [leaves]) — citronellal, citronellol, Z-3-hexenal (Bioscience, Biotechnology and Biochemistry, 61, 491, 1997)

- Zanthoxylum acanthopodium (Indonesia) — citronellal, limonene[14]

U.S. import ban

From 1968 to 2005,[15] the United States Food and Drug Administration banned the importation of Sichuan peppercorns because they were found to be capable of carrying citrus canker (as the tree is in the same family, Rutaceae, as the genus Citrus). This bacterial disease, which is very difficult to control, could potentially harm the foliage and fruit of citrus crops in the U.S. It was never an issue of harm in human consumption. The import ban was only loosely enforced until 2002.[16] In 2005, the USDA and FDA lifted the ban, provided the peppercorns are heated to around 70 °C (158 °F) to kill any canker bacteria before import.

References

- 1 2 Hu 2005, p. 504

- ↑ Johnson, Elaine. These Asian spices are lively secrets. Sunset, 1 March 1993.

- ↑ 临夏县概况 (Linxia County overview)

- 1 2 3 4 http://gernot-katzers-spice-pages.com/engl/Zant_pip.html

- 1 2 Zhang & Hartley 2008

- ↑ Hu 2005, p.504

- ↑ Zhou, Jiaju; Xie, Guirong; Yan, Xinjian (2011), Encyclopedia of Traditional Chinese Medicines - Molecular Structures (preview), 1, Springer, p.209

- ↑ zh:花椒 (retrieved from ver. 2011.12.20 11:55)

- ↑ Hu 2005

- ↑ aayisrecipes.com

- ↑ Garrett, J. T. (2003), The Cherokee herbal: native plant medicine from the four directions (preview), Inner Traditions / Bear, ISBN 9781879181960, p.184

- ↑ McGee, Harold (2007). On Food and Cooking: The Science and Lore of the Kitchen. New York: Scribner. p. 429. ISBN 978-1-4165-5637-4.

- ↑ Levine, Jonathan (June 20, 2013). "Beijing's microbrewery boom". CNN. Retrieved May 13, 2015.

- ↑ Wijaya, CH; I Triyanti; A Apriyantono (2002). "Identification of volatile compounds and key aroma compounds in andaliman fruit (Zanthoxylum acanthopodium)". Journal of Food Science Biotechnology. 11 (6): 680–683.

- ↑ http://www.ecfr.gov/cgi-bin/text-idx?SID=33acb14307df8d21bb6cf83ad438d2b3&node=7:5.1.1.1.6.6.34.1&rgn=div8

- ↑ Landis, Denise (4 February 2004). "Sichuan's Signature Fire Is Going Out. Or Is It?". The New York Times. p. F1.

Sources

- Hu, Shiu-ying (2005), Food plants of China (preview), 1, Chinese University Press

- Zhou, Jiaju; Xie, Guirong; Yan, Xinjian (2011), Encyclopedia of Traditional Chinese Medicines - Molecular Structures (preview), 1, Springer

- Zhang, Dianxiang; Hartley, Thomas G. (2008), "1. Zanthoxylum Linnaeus, Sp. Pl. 1: 270. 1753.", Flora of China, 11: 53–66 PDF

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sichuan pepper. |

- Gernot Katzer's spice pages

- Recipes