Scheduled monuments in Greater Manchester

There are 37 scheduled monuments in Greater Manchester, a metropolitan county in North West England. In the United Kingdom, a scheduled monument is a "nationally important" archaeological site or historic building that has been given protection against unauthorised change by being placed on a list (or "schedule") by the Secretary of State for Culture, Media and Sport; English Heritage takes the leading role in identifying such sites.[1] Scheduled monuments are defined in the Ancient Monuments and Archaeological Areas Act 1979 and the National Heritage Act 1983. They are also referred to as scheduled ancient monuments. There are about 18,300 scheduled monument entries on the list, which is maintained by English Heritage; more than one site can be included in a single entry. While a scheduled monument can also be recognised as a listed building, English Heritage considers listed building status as a better way of protecting buildings than scheduled monument status.[1] If a monument is considered by English Heritage to "no longer merit scheduling" it can be descheduled.[2]

The metropolitan county of Greater Manchester is composed of 10 metropolitan boroughs: Bolton, Bury, Manchester, Oldham, Rochdale, Salford, Stockport, Tameside, Trafford and Wigan. Rochdale has no scheduled monuments; those in the other boroughs are listed separately. They range from prehistoric structures – the oldest of which date from the Bronze Age – to more modern structures such as the Astley Green Colliery, from 1908. Greater Manchester has seven prehistoric monuments (i.e. Bronze or Iron Age), found in Bury, Oldham, Salford, Stockport, and Tameside. The Bronze Age sites are mainly cairns and barrows, and both the Iron Age sites are military in nature, promontory forts.

The trend of military sites continues from the Iron Age into the Roman period; two Roman forts in Greater Manchester are scheduled monuments and were the two main areas of Roman activity in the county. Of the nine castles in Greater Manchester, four are scheduled monuments: Buckton Castle, Watch Hill Castle, Bury Castle, and Radcliffe Tower. The last two are fortified manor houses, and although defined as castles were not exclusively military in nature; they probably acted as the administrative centre of the manors they were in.[3] There are several other manor houses and country houses – some with moats – in the county that are protected as scheduled monuments. The Astley Green Colliery, the Marple Aqueduct, Oldknows Limekilns, and the Worsley Delph are scheduled relics of Greater Manchester's industrial history.

Bolton

Bury

Manchester

Oldham

Salford

Stockport

Tameside

Trafford

Wigan

|

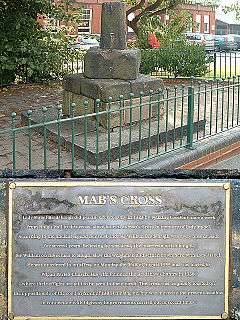

Ringley Old Bridge in Ringley  Affetside Cross replaced an earlier medieval cross  The standing remains of Radcliffe Tower  The 14th-century Baguley Hall, in Baguley is also a Grade I listed building  Clayton Hall, in Clayton is also a Grade II* listed building  A reconstructed section of the wall of Mamucium fort  Hanging Bridge was excavated in 1892  Looking west along Nico Ditch, near Levenshulme  A plan of Castleshaw drawn by Thomas Percival in 1752 showing the fort and the later fortlet  The Marple Aqueduct crossing the River Goyt  View of Buckton Castle from below  Astley Green Colliery's pithead, viewed from across the Bridgewater Canal  Winstanley Hall, a Tudor house, is also a Grade II* listed building  Mab's Cross is a Grade II* listed building |

See also

- Architecture of Manchester

- Castles in Greater Manchester

- Conservation in the United Kingdom

- Grade I listed buildings in Greater Manchester

- Grade II* listed buildings in Greater Manchester

- List of tallest buildings in Manchester

Notes

- A Most references are to one main body of sources: Pastscape which is funded by English Heritage and has information on nearly 400,000 archaeological sites and buildings in England.

"The information on PastScape is derived from the National Monuments Record database which holds records on the architectural and archaeological heritage of England. The National Monuments Record is the public archive of English Heritage."[70]

- B Nico Ditch is a linear earthwork that runs for about 6 miles (9.7 km) generally east to west. It forms part of the Manchester–Tameside border and the Manchester–Stockport border. It passes through Tameside and Manchester and extends into Trafford as far as Stretford. A 135 m (443 ft) long stretch of the ditch in Platt Fields is protected.[24][25]

References

- 1 2 The Schedule of Monuments, Pastscape.org.uk, archived from the original on 23 February 2009, retrieved 4 February 2009

- ↑ Archaeological activities undertaken by English Heritage, English Heritage, retrieved 15 February 2009

- ↑ Friar (2003), pp. 186–87.

- ↑ Historic England, "Ringley Old Bridge (44221)", PastScape, retrieved 1 February 2009

- ↑ Historic England, "Ringley Old Bridge (210526)", Images of England, retrieved 1 February 2009

- ↑ Historic England, "Smithills Hall (43437)", PastScape, retrieved 1 February 2009

- ↑ Historic England, "Smithills Hall Fold (358003)", Images of England, retrieved 1 February 2009

- ↑ Historic England, "Affetside Cross (44366)", PastScape, retrieved 30 December 2007

- ↑ Historic England, "Bury Castle (45189)", PastScape, retrieved 4 February 2009

- ↑ Historic England, "Castlesteads (44369)", PastScape, retrieved 30 December 2007

- ↑ Historic England, "Radcliffe Tower (44210)", PastScape, retrieved 30 December 2007

- ↑ The parish of Radcliffe, A History of the County of Lancaster: Volume 5 (1911), pp. 56–67. URL: http://www.british-history.ac.uk/report.aspx?compid=53000, retrieved on 25 October 2008

- ↑ Historic England, "Baguley Hall (76516)", PastScape, retrieved 5 February 2009

- ↑ Baguley Hall, Hall Lane, English Heritage, retrieved 5 February 2009

- ↑ Historic England, "Baguley Hall (388166)", Images of England, retrieved 5 February 2009

- ↑ Historic England, "Clayton Hall (76619)", PastScape, retrieved 5 February 2009

- ↑ Historic England, "Clayton Hall, Manchester (387908)", Images of England, retrieved 5 February 2009

- ↑ Historic England, "Hanging Bridge over Hanging Ditch (76682)", PastScape, retrieved 30 December 2007

- ↑ Bridge to Manchester's past revealed, BBC, 18 December 2001, retrieved 4 April 2008

- ↑ Cooper (2003), p. 52.

- ↑ Historic England, "Mamucium Roman fort (76731)", PastScape, retrieved 30 December 2007

- ↑ Norman Redhead (20 April 2008), A guide to Mamucium, BBC Online, retrieved 20 July 2008

- ↑ Gregory (2007), pp. 3, 22, 156, 190.

- 1 2 Historic England, "Nico Ditch (1033812)", PastScape, retrieved 11 February 2009

- 1 2 Nevell (1992), p. 77-83.

- ↑ Historic England, "Peel Hall (76526)", PastScape, retrieved 30 December 2007

- ↑ Historic England, "Rigodunum Roman fort (45891)", PastScape, retrieved 30 December 2007

- ↑ Redhead (1999), p. 81.

- ↑ Redhead (1999), pp. 74–81.

- ↑ Walker (1989), p. 20.

- ↑ Nevell and Redhead (2005), p. 59.

- ↑ Brennaud (2006), p. 65.

- ↑ Historic England, "Bowl Barrow (45895)", PastScape, retrieved 1 February 2009

- ↑ Historic England, "Monument No. 73547", PastScape, retrieved 5 February 2009

- ↑ Historic England, "Worsley Delph (44278)", PastScape, retrieved 30 December 2007

- ↑ Historic England, "Brown Low (78554)", PastScape, retrieved 4 February 2009

- ↑ Historic England, "Bronze Age cairn in Ludworth (890910)", PastScape, retrieved 4 January 2008

- ↑ Historic England, "Marple Goyt Aqueduct (78557)", PastScape, retrieved 4 February 2009

- ↑ Historic England, "Oldknows Limekilns (78346)", PastScape, retrieved 5 February 2009

- ↑ Historic England, "Walling at old lime kiln (441896)", Images of England, retrieved 5 February 2009

- ↑ Historic England, "Peel Hall, Stockport (76845)", PastScape, retrieved 5 February 2009

- ↑ Historic England, "Torkington Moat (78351)", PastScape, retrieved 5 February 2009

- ↑ Nevell (1998), pp. 60–61, 63.

- ↑ P. Booth, M. Harrop & S. Harrop, The Extent of Longdendale, 1360, Cheshire Sheaf, 5th series, #83

- ↑ Grimsditch, Nevell, and Redhead (2007), pp. 5, 16.

- ↑ Grimsditch, Nevell & Nevell (2012), pp. 82–85.

- ↑ Historic England, "Monument No. 78454", PastScape, retrieved 1 February 2009

- ↑ Historic England, "Watch Hill Castle (74893)", PastScape, retrieved 30 December 2007

- ↑ Nevell (1997), pp. 27, 34.

- ↑ Historic England, "Astley Green Colliery (623407)", PastScape, retrieved 5 February 2009

- ↑ Historic England, "Cross base at junction of Green Lane, Standish Wood Lane and Beech Walk, Standish (41980)", PastScape, retrieved 5 February 2009

- ↑ Historic England, "Cross base on Green Lane, Standish (41983)", PastScape, retrieved 5 February 2009

- ↑ Historic England, "Cross base (403065)", Images of England, retrieved 5 February 2009

- ↑ Historic England, "Cross base on Standish Wood Lane, Standish (41972)", PastScape, retrieved 30 December 2007

- ↑ Historic England, "Gidlow Hall (43321)", PastScape, retrieved 6 February 2009

- ↑ Historic England, "Gidlow Hall (213577)", Images of England, retrieved 6 February 2009

- ↑ Historic England, "Haigh Sough mine drainage portal (41959)", PastScape, retrieved 30 December 2007

- ↑ Historic England, "Mab's Cross (41800)", PastScape, retrieved 6 February 2009

- ↑ Historic England, "Mab's Cross, Wigan (484960)", Images of England, retrieved 18 May 2008

- ↑ Historic England, "Market Cross (42326)", PastScape, retrieved 5 February 2009

- ↑ Historic England, "Village Cross (403069)", Images of England, retrieved 5 February 2009

- ↑ Historic England, "The Moat House (43314)", PastScape, retrieved 5 February 2009

- ↑ Historic England, "Morleys Hall (73466)", PastScape, retrieved 5 February 2009

- ↑ Historic England, "Morley's Hall (213522)", Images of England, retrieved 5 February 2009

- ↑ Historic England, "New Hall (43339)", PastScape, retrieved 6 February 2009

- ↑ Historic England, "Winstanley Hall (42086)", PastScape, retrieved 6 February 2009

- ↑ Historic England, "Winstanley Hall (402576)", Images of England, retrieved 6 February 2009

- ↑ Scheduled Ancient Monuments in Wigan, Wigan.gov.uk, archived from the original on 6 March 2007, retrieved 5 February 2009

- ↑ Newsletter #52, Wigan Archaeological Society, April 2002, retrieved 6 February 2009

- ↑ About PastScape, Pastscape.org.uk, retrieved 30 December 2007

Bibliography

- Brennand, Mark (ed) (2006), The Archaeology of North West England, Council for Archaeology North West, ISSN 0962-4201

- Cooper, Glynis (2003), Hidden Manchester, Breedon Books Publishing, ISBN 1-85983-401-9

- Friar, Stephen (2003), The Sutton Companion to Castles, Stroud: Sutton Publishing, ISBN 978-0-7509-3994-2

- Gregory, Richard (ed) (2007), Roman Manchester: The University of Manchester's Excavations within the Vicus 2001–5, Oxford: Oxbow Books, ISBN 978-1-84217-271-1

- Grimsditch, Brian; Nevell, Mike; Redhead, Norman (September 2007), Buckton Castle: An Archaeological Evaluation of a Medieval Ringwork – an Interim Report, University of Manchester Archaeological Unit

- Grimsditch, Brian; Nevell, Michael; Nevell, Richard (2012), Buckton Castle and the Castles of North West England, University of Salford Archaeological Monographs volume 2 and the Archaeology of Tameside volume 9, Centre for Applied Archaeology, School of the Built Environment, University of Salford, ISBN 978-0-9565947-2-3

- Nevell, Mike (1992), Tameside Before 1066, Tameside Metropolitan Borough Council, ISBN 1-871324-07-6

- Nevell, Mike (1997), The Archaeology of Trafford, Trafford Metropolitan Borough with University of Manchester Archaeological Unit, ISBN 1-870695-25-9

- Nevell, Mike (1998), Lands and Lordships in Tameside, Tameside Metropolitan Borough Council with the University of Manchester Archaeological Unit, ISBN 1-871324-18-1

- Nevell, Mike and Redhead, Norman (eds) (2005), Mellor: Living on the Edge. A Regional Study of an Iron Age and Romano-British Upland Settlement, University of Manchester Archaeological Unit, Greater Manchester Archaeological Unit, and the Mellor Archaeological Trust, ISBN 0-9527813-6-0

- Walker, John (ed) (1989), Castleshaw: The Archaeology of a Roman Fortlet, Greater Manchester Archaeological Unit, ISBN 0-946126-08-9