Saxe-Lauenburg

| Duchy of Saxe-Lauenburg | ||||||||||

| Herzogtum Sachsen-Lauenburg | ||||||||||

| State of the Holy Roman Empire State of the German Confederation State of the North German Confederation State of the German Empire | ||||||||||

| ||||||||||

Flag

Coat of arms

as used 1507–1671 | ||||||||||

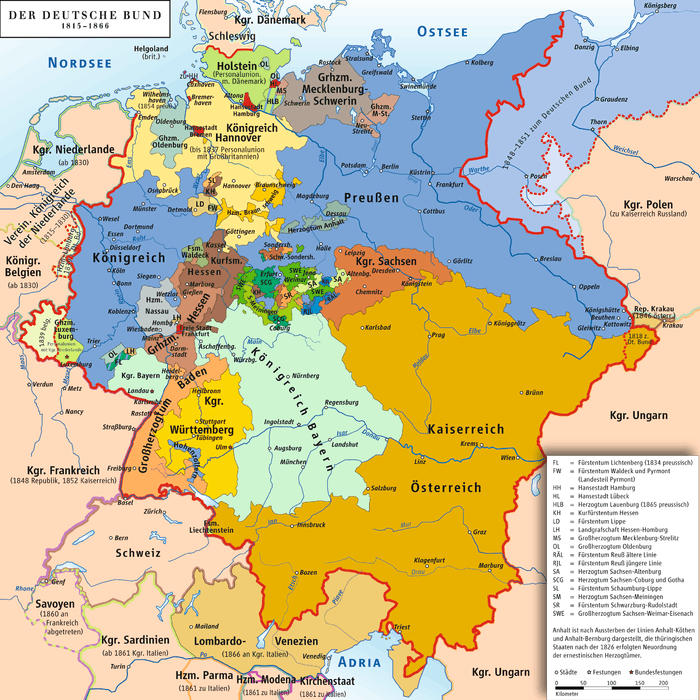

Saxe-Lauenburg in 1848 (map in Dutch) | ||||||||||

| Capital | Lauenburg/Elbe Ratzeburg (from 1619) | |||||||||

| Government | Principality | |||||||||

| Historical era | Middle Ages | |||||||||

| • | Partitioned from Duchy of Saxony | 1296 | ||||||||

| • | Partitioned into Saxe-Mölln-Bergedorf and Saxe-Ratzeburg | 1303–1401 | ||||||||

| • | Personal union: - with Lüneburg-Celle - with Hanover |

1689–1705 1705–1803 | ||||||||

| • | Dissolved during Napoleonic Wars |

1803–1814 | ||||||||

| • | Personal union: - with Denmark - with Prussia |

1814–1864 1865–1876 | ||||||||

| • | Merged into Prussia | 1876 | ||||||||

| ||||||||||

The Duchy of Saxe-Lauenburg (German: Herzogtum Sachsen-Lauenburg, called Niedersachsen (Lower Saxony) between the 14th and 17th centuries), was a reichsfrei duchy that existed 1296–1803 and 1814–1876 in the extreme southeast region of what is now Schleswig-Holstein. Its territorial center was in the modern district of Herzogtum Lauenburg and originally its eponymous capital was Lauenburg upon Elbe, though in 1619 the capital moved to Ratzeburg.

Former territories not part of today's district of Lauenburg

In addition to the core territories in the modern district of Lauenburg, at times other territories, mostly south of the river Elbe, belonged to the duchy:

- The tract of land along the southern Elbe bank (German: Marschvogtei), reaching from Marschacht to the Amt Neuhaus, territorially connecting the core of the duchy with these more southeastern Lauenburgian areas. This land was ceded to the Kingdom of Hanover in 1814. It is now part of the Lower Saxon Harburg (district).

- The Amt Neuhaus proper, then including areas on both sides of the Elbe, which was ceded to the Kingdom of Hanover in 1814. Today, this is all part of Lower Saxon Lüneburg (district).

- The exclave Land of Hadeln in the area of the Elbe estuary was disentangled from Saxe-Lauenburg in 1689 and administered as a separate territory under imperial custody, before it was ceded to Bremen-Verden in 1731. Now it is part of today's Lower Saxon Cuxhaven (district).

- Some North Elbian municipalities of the former core duchy are not part of today's district of Lauenburg, since they had been ceded to the then Soviet occupation zone by the Barber Lyashchenko Agreement in November 1945.

History

Early history

In 1203, King Valdemar II of Denmark conquered the area later comprising Saxe-Lauenburg, but it reverted to Albert I, Duke of Saxony in 1227.[2] In 1260, Albert I's sons Albert II and John I succeeded their father.[2] In 1269, 1272 and 1282, the brothers gradually divided their governing competences within the three territorially unconnected Saxon areas along the Elbe river (one called Land of Hadeln, another around Lauenburg upon Elbe and the third around Wittenberg upon Elbe), thus preparing a partition.

After John I's resignation, Albert II ruled with his minor nephews Albert III, Eric I and John II, who by 1296 definitely partitioned Saxony providing Saxe-Lauenburg for the brothers, and Saxe-Wittenberg for their uncle Albert II. The last document, mentioning the brothers and their uncle Albert II as Saxon fellow dukes dates back to 1295.[3] A deed of 20 September 1296, mentions the Vierlande, Sadelbande (Land of Lauenburg), the Land of Ratzeburg, the Land of Darzing (later Amt Neuhaus), and the Land of Hadeln as the separate territory of the brothers.[3]

By 1303, the three jointly ruling brothers had partitioned Saxe-Lauenburg into three shares, however, Albert III died already in 1308, so that the surviving brothers established, after a territorial realignment in 1321, the Lauenburg Elder Line, with John II ruling Saxe-Bergedorf-Mölln, seated in Bergedorf and the Lauenburg Younger Line, with Eric I ruling Saxe-Ratzeburg-Lauenburg, seated in Lauenburg upon Elbe. John II, the eldest brother, wielded the electoral privilege for the Lauenburg Ascanians, however, rivalled by their cousin Rudolph I of Saxe-Wittenberg.

In 1314, the dispute escalated into the election of two hostile German kings, the Habsburg Frederick III, the Fair, and his Wittelsbach cousin Louis IV, the Bavarian. Louis received five of the seven votes, to wit Archbishop-Elector Baldwin of Trier, the legitimate King-Elector John of Bohemia, Duke John II of Saxe-Lauenburg using his claim as the Saxon prince-elector, Archbishop-Elector Peter of Mainz, and Prince-Elector Waldemar of Brandenburg.

Frederick the Fair received in the same election four of the seven votes, with the deposed King-Elector Henry of Bohemia, illegitimately assuming electoral power, Archbishop-Elector Henry II of Cologne, Louis's brother Prince-Elector Rudolph I of the Electorate of the Palatinate, and Duke Rudolph I of Saxe-Wittenberg, rivallingly claiming the Saxon prince-electoral power. However, only Louis the Bavarian finally asserted himself as emperor of the Holy Roman Empire. The Golden Bull of 1356, however, conclusively named the dukes of Saxe-Wittenberg as electors.

In 1370, John II's fourth successor Eric III of Saxe-Bergedorf-Mölln pawned the Herrschaft of Bergedorf, the Vierlande, half the Saxon Wood and Geesthacht to Lübeck in return for a credit of 16,262.5 Lübeck marks.[4] This acquisition included much of the trade route between Hamburg and Lübeck, thus providing a safe passage for freight between the cities. Eric III only retained a life tenancy.

The city of Lübeck and Eric III had stipulated that, upon his death, Lübeck would be entitled to take possession of the pawned areas until his successors repaid the credit and simultaneously exercised the repurchase of Mölln (contracted in 1359), altogether amounting to the then enormous sum of 26,000 Lübeck Marks.[5]

In 1401, Eric III died without issue. The Lauenburg Elder Line was thus extinct in the male line and Eric III was succeeded by his second cousin Eric IV of Saxe-Ratzeburg-Lauenburg of the Younger Line. In the same year, Eric IV, supported by his sons Eric (later ruling as Eric V) and John, forcefully captured the pawned areas without making any repayment, before Lübeck could take possession of them. Lübeck acquiesced for the time being.[6]

In 1420, Eric V attacked Prince-Elector Frederick I of Brandenburg and Lübeck allied with Hamburg in support of Brandenburg. Armies of both cities opened a second front and conquered Bergedorf, Riepenburg castle and the Esslingen river toll station (today's Zollenspieker Ferry). This forced Eric V to agree with Hamburg's burgomaster Hein Hoyer and Burgomaster Jordan Pleskow of Lübeck to the Treaty of Perleberg on 23 August 1420, which stipulated that all the pawned areas, which Eric IV, Eric V and John IV had violently taken in 1401, were to be irrevocably ceded to the cities of Hamburg and Lübeck, becoming their bi-urban condominium of Bergedorf (Beiderstädtischer Besitz).

From the 14th century, Saxe-Lauenburg termed itself as Lower Saxony (German: Niedersachsen).[7] However, Saxony as a naming for the area comprising the older Duchy of Saxony in its borders before 1180 still prevailed. So, when in 1500 the Holy Roman Empire established the Imperial Circles as tax levying and army recruitment districts, the circle comprising Saxe-Lauenburg and all its neighbours became designated as Saxon Circle, while the Wettin-ruled Saxon electorate and duchies at that time formed the Upper Saxon Circle. The naming of Lower Saxony became more colloquial and the Saxon Circle was later renamed into Lower Saxon Circle. In 1659, Duke Julius Henry decreed in his general disposition (guidelines for his government) "to also esteem the woodlands as heart and dwell [of revenues] of the Principality of Lower Saxony."[8]

The people of Hadeln, represented by their estates of the realm, adopted the Lutheran Reformation in 1525 and Duke Magnus I confirmed Hadeln's Lutheran Church Order in 1526, establishing Hadeln's separate ecclesiastical body existing until 1885.[9] Magnus did not promote the spreading of Lutheranism in the rest of his duchy.[10] Lutheran preachers, most likely from the southerly adjacent Principality of Lunenburg, Lutheran since 1529, held the first Lutheran preaches; at the northern entrance of St. Mary Magdalene Church in Lauenburg upon Elbe one is recalled for St John's Eve in 1531.[10] Tacitly, the congregations appointed Lutheran preachers so that the visitations of 1564 and 1566, ordered by Duke Francis I, Magnus I's son, on the instigation of the Ritter- und Landschaft, saw already Lutheran preachers in many parishes.[11] In 1566, Francis I appointed the Superintendent Franciscus Baringius as the first spiritual leader of the church in the duchy, not including Hadeln.[12]

Francis I conducted a thrifty reign and resigned in favour of his eldest son Magnus II once having exploited all his means in 1571. Magnus II promised to redeem the pawned ducal demesnes with funds he gained as a Swedish military commander and by his marriage to Princess Sophia of Sweden. However, Magnus did not redeem pawns but further alienated ducal possessions, which ignited a conflict between Magnus and his father and brothers Francis (II) and Maurice as well as the estates of the duchy, further escalating due to Magnus' violent temperament.

In 1573, Francis I deposed Magnus and reascended to the throne while Magnus fled to Sweden. The following year Magnus hired troops in order to take Saxe-Lauenburg with violence. Francis II, an experienced military commander in imperial service, and Duke Adolphus of Schleswig and Holstein at Gottorp, then Lower Saxon Circle Colonel (Kreisobrist), helped Francis I to defeat Magnus. In return Saxe-Lauenburg had to cede the bailiwick of Steinhorst to Gottorp in 1575. Francis II again helped his father to inhibit Magnus' second military attempt to overthrow his father in 1578.[13] Francis I then made Francis II his vicegerent actually governing the duchy.

In 1581 - shortly before he died and after consultations with his son Prince-Archbishop Henry of Bremen and Emperor Rudolph II, but unconcerted with his other sons Magnus and Maurice - Francis I made his third son Francis II, whom he considered the ablest, his sole successor, violating the rules of primogeniture.[14] This severed the anyway difficult relations with the estates of the duchy, which fought the ducal practice of growing indebtedness.[14]

The general church visitation of 1581, prompted by Francis II, showed poor results as to the knowledge, practice and behaviour of many pastors.[15] Baringius was held responsible for these grievances and replaced by Gerhard Sagittarius in 1582.[16] Finally in 1585, after consultations with his brother Prince-Archbishop Henry, Francis II decreed a constitution (Niedersächsische Kirchenordnung; Lower Saxon Church Order), authored by Lübeck's Superintendent Andreas Pouchenius the Elder, for the Lutheran church of Saxe-Lauenburg.[17] It constituted the Lutheran state church of Saxe-Lauenburg, with general superintendent (as of 1592) and consistory seated in the city of Lauenburg, which merged into that of Schleswig Holstein in 1877. Francis II's attempt to merge Hadeln's Lutheran church body with that in the rest of the duchy was unanimously rejected by Hadeln's clergy and estates in 1585 and 1586.[18]

The violation of the primogeniture, however, gave grounds for the estates to perceive the upcoming duke Francis II as illegitimate. This forced him into negotiations, which ended on 16 December 1585 with the constitutional act of the "Eternal Union" (German: Ewige Union) of the representatives of Saxe-Lauenburg's nobility (Ritterschaft, i.e. knighthood) and other subjects (Landschaft), mostly from the cities, Lauenburg upon Elbe and Ratzeburg, then altogether constituted as the estates of the duchy (Ritter- und Landschaft), led by the Land Marshall, a hereditary office held by the family von Bülow. Francis II accepted their establishment as a permanent institution with a crucial say in government matters. In return Ritter- und Landschaft accepted Francis II as legitimate and rendered him homage as duke in 1586.

The relations between Ritter- und Landschaft and duke improved since Francis II redeemed ducal pawns with money he had earned as imperial commander.[19] After the residential castle in Lauenburg upon Elbe (started in 1180–1182 by Duke Bernard I) had burnt down in 1616, Francis II moved the capital to Neuhaus upon Elbe.[20]

In 1619 Duke Augustus moved Saxe-Lauenburg's capital from Neuhaus upon Elbe to Ratzeburg, where it remained since.[20] During the Thirty Years' War (1618–1648) Augustus always remained neutral, however, billeting and alimenting foreign troops marching through posed a heavy burden onto the ducal subjects.[19] Augustus was succeeded by his elder half-brother Julius Henry in 1656. He had converted from Lutheranism to Catholicism in expectation of becoming appointed Prince-Bishop of Osnabrück in 1615, but guaranteed to leave the Lutheran state church and the Lower Saxon Church Order untouched.[21]

He confirmed the existing privileges of the nobility and the Ritter- und Landschaft. In 1658 he forbade his vassals to pledge or else alienate fiefs, thus fighting the integration of manor estates in Saxe-Lauenburg into the monetary economies of the neighbouring economically powerful Hanseatic cities of Hamburg and Lübeck. He entered with both city-states into frontier disputes on manor estates which were in the process of evading Saxe-Lauenburgian overlordship into the competence of the city-states.

With the death of Duke Julius Francis, a son of Julius Henry, the Lauenburg line of the House of Ascania became extinct in the male line.[2] However, female succession was possible by the Saxe-Lauenburgian laws. So the two surviving out of the three daughters of Julius Francis, Anna Maria Franziska of Saxe-Lauenburg and Sibylle Auguste of Saxe-Lauenburg fought for the succession of the former, the elder sister. Their weakness was abused by Duke George William of the neighbouring Brunswick and Lunenburgian Principality of Lunenburg, seated in Celle, who invaded Saxe-Lauenburg with his troops,[2] thus inhibiting the ascension of the legal heiress to the throne Duchess Anna Maria.

There were at least eight monarchies claiming the succession,[2] resulting in a conflict involving further the neighbouring duchies of Mecklenburg-Schwerin and of Danish Holstein, as well as the five Ascanian-ruled Principalities of Anhalt, the Electorate of Saxony, which had succeeded the Saxe-Wittenbergian Ascanians in 1422, Sweden and Brandenburg. Militarily engaged were Celle and Danish Holstein, which agreed on 9 October 1693 (Hamburger Vergleich), that Celle anyway de facto holding most of Saxe-Lauenburg would retain the duchy, while the fortress in Ratzeburg, fortified under Celle rule and directed against Holstein, would be razed. In return Danish Holstein, which had invaded Ratzeburg and ruined the fortress, would withdraw its troops.

George William compensated John George III, Elector of Saxony, for his claim by a substantial sum of money, since the ancestors of both these princes had made treaties of mutual succession with former dukes of Saxe-Lauenburg.[2] The Ritter- und Landschaft then rendered homage to George William as their duke.[2] On 15 September 1702 George William confirmed the existing constitution, laws and legislative bodies of Saxe-Lauenburg.[22] On 17 May 1705 the Lutheran superintendency was moved from Lauenburg to Ratzeburg and combined with the pastorate of St. Peter's Church.[23] When he died on 28 August the same year Saxe-Lauenburg passed to his nephew, George I Louis, elector of Hanover, afterwards king of Great Britain as George I.[2] The Lower Saxon Lutheran Church maintained its Church Order with the consistory and General Superintendent Severin Walter Slüter (1646–1697) in Lauenburg, succeeded by incumbents titled again superintendent only.[24]

So Saxe-Lauenburg, except for Hadeln, passed to the House of Welf and its cadet branch House of Hanover, while the legal heirs, Anna Maria Franziska of Saxe-Lauenburg and Sibylle Auguste of Saxe-Lauenburg, never waiving their claim, were dispossessed and the former exiled in Bohemian Ploskovice. Emperor Leopold I rejected Celle's succession and thus retained Hadeln, which was out of Celle's reach, in his custody. Only in 1728 his son Emperor Charles VI enfeoffed George II Augustus with Saxe-Lauenburg, finally legitimising the de facto takeover by his grandfather in 1689 and 1693.[2] On 27 August 1729 he confirmed Saxe-Lauenburg's existing constitution, laws and the Ritter- und Landschaft.[22] On 5 April 1757 the Niedersächsische Landschulordnung decreed the compulsory school attendance for all children in Saxe-Lauenburg.[25] George III ascended in 1760 and endorsed all the laws, the constitution and the Ritter- und Landschaft of Saxe-Lauenburg by a writ issued in St. James' Palace on 21 January 1765.[22] In 1794 George III donated annual rewards for the best teachers in Saxe-Lauenburg.[26]

Napoleonic era

The duchy was occupied by French troops in 1803–05,[2] after which the French occupational troops left in a campaign against Austria. Then British, Swedish and Russian Coalition forces captured Saxe-Lauenburg in autumn 1805 at the beginning of the War of the Third Coalition against France (1805–06). In December the Empire of the French, since 1804 France's new form of government, ceded Saxe-Lauenburg, which it no longer held, to Brandenburg-Prussia, which captured it early in 1806.

But when the Kingdom of Prussia (the name element Electorate of Brandenburg had turned void at the dissolution of the Holy Roman Empire on 6 August 1806), after it had turned – as part of the Fourth Coalition – against France, was defeated in the Battle of Jena-Auerstedt (November 11, 1806), France recaptured Saxe-Lauenburg. In remained first under French occupation, before on 1 March 1810 most of it was annexed to the Kingdom of Westphalia, a French client state. A small area with 15,000 inhabitants remained reserved for Napoléon's purposes. On 1 January 1811, most of the former duchy – except for the Amt Neuhaus and the Marschvogtei, which remained with Westphalia – was annexed to the First French Empire.[2]

Post-Napoleon

After the Napoleonic Wars, Saxe-Lauenburg was restored as a Hanoverian dominium in 1813.[2] The Congress of Vienna established Saxe-Lauenburg as a member state of the German Confederation. In 1814 the Kingdom of Hanover bartered Saxe-Lauenburg against royally Prussian East Frisia. On 7 June 1815, after 14 months under its rule, Prussia granted Saxe-Lauenburg to Sweden, receiving in return prior Swedish Pomerania, however, additionally paying 2.6 million Taler to Denmark, in order to compensate Danish claims to Pomerania.[27] Denmark gained that ducal territory north of the Elbe, now ruled in personal union by the Danish House of Oldenburg,[2] from Sweden, which thus again compensated Danish claims to Swedish Pomerania. On 6 December 1815 Frederick VI of Denmark issued his Asseveration Act (Versicherungsacte) affirming the given laws, the constitution and the Ritter- und Landschaft of Saxe-Lauenburg.[22] In 1816 his administration took possession of the duchy.[2]

During the First Schleswig War (1848–1851), the Ritter- und Landschaft prevented a Prussian conquest by requesting Hanoverian troops as peace-keeping occupational forces on behalf of the German Confederation.[2] In 1851 King Frederick VII of Denmark was restored in his power as Duke of Saxe-Lauenburg.[2] Prussian and Austrian forces invaded the duchy during the Second Schleswig War. By the Treaty of Vienna (1864), King Christian IX of Denmark resigned as duke and ceded the duchy to Prussia and Austria.[2] After receiving a £300,000 financial compensation, Austria waived its claim to Saxe-Lauenburg by the Gastein Convention in August 1865.[2] The Ritter- und Landschaft then offered the ducal throne to William I of Prussia. In September the same year, he accepted and ruled the duchy in personal union since.[2] William appointed the then Minister President of Prussia, Otto von Bismarck, as minister for Saxe-Lauenburg. In 1866, Saxe-Lauenburg joined the North German Confederation.[2] However, its vote in the Bundesrat was counted along with those of Prussia.

In 1871, Saxe-Lauenburg was one of the component constituent states founding united Germany.[2] However, in 1876, the ducal government and the Ritter- und Landschaft decided to dissolve the Duchy with effect on 1 July 1876.[2] Its territory was then integrated into the Prussian Province of Schleswig-Holstein as the district Herzogtum Lauenburg, meaning the Duchy of Lauenburg.

For the further history see Herzogtum Lauenburg.

Dukes of Saxe-Lauenburg

For the Duchesses consort see List of Saxon consorts, partially also presenting portraits. For portraits of the dukes, starting with Julius Henry, see List of Saxon rulers.

House of Ascania (1296–1689)

The counting of the dukes includes the preceding Ascanian dukes Bernard I, his son Albert I, and the latter's jointly ruling sons John I and Albert II, all of which ruled the Saxon dukedom before its partition into Saxe-Lauenburg and Saxe-Wittenberg.

- Eric I 1296–1303 joint rule, then ruling until 1360 in Saxe-Bergedorf, partitioned from Saxe-Lauenburg (see #Ratzeburg-Lauenburg line below)

- John II 1296–1303 joint rule, then ruling until 1321 in Saxe-Ratzeburg, partitioned from Saxe-Lauenburg (see section #Bergedorf-Mölln line below)

- Albert III 1296–1303 joint rule, then ruling until 1308 in Saxe-Ratzeburg, partitioned from Saxe-Lauenburg, dying without issue Eric I inherited his share

In 1303 the brothers split their inheritance between them, however, only two brothers had heirs creating the Bergedorf-Mölln and the Ratzeburg-Lauenburg lines.

Bergedorf-Mölln line

First named Saxe-Mölln, however, renamed following a territorial redeployment including parts of Albert III's share in 1321.

- 1303–22: John II (*ca. 1275–1322*), ruled alone in Bergedorf-Mölln, rivalled as Saxon Prince-Elector by his cousin Rudolph I of Saxe-Wittenberg in 1314

- 1322–43: Albrecht (Albert) IV (*?–1343*), son of the preceding.

- 1343–56: John III (*?–1356*), son of the preceding.

- 1356–70: Albrecht (Albert) V (*?–1370*), brother of the preceding.

- 1370–1401: Eric III (*?–1401*), brother of the preceding.

In 1401, the elder branch became extinct and Lauenburg rejoined the Ratzeburg-Lauenburg line.

Ratzeburg-Lauenburg line

First named Saxe-Bergedorf-Lauenburg, however, renamed following a territorial redeployment after inheriting Albert III's share.

- 1303–38: Eric I (*?–1360*), resigned in 1338.

- 1338–68: Eric II (*1318/1320–1368*), son of the preceding.

- 1368–1412: Eric IV (*1354–1411/1412*), son of the preceding, ruled jointly with his sons Eric V and Bernard II since 1401.[28]

In 1401, the younger branch inherited Lauenburg and other possessions of the extinct elder Bergedorf-Mölln line.

- 1401–36: Eric V (*?-1436*), son of the preceding, ruled jointly with his father until 1412, his brother John IV until 1414 and his younger brother Bernard II as of 1426.

- 1401–14: John IV (*?-1414*), brother of the preceding, ruled jointly with his father until 1412 and his brother Eric V.

- 1426–63: Bernard II (*1385/1392–1463*), brother of the preceding, ruled jointly with his brother Eric V as of 1426.[29]

- 1463–1507: John V (*1439–1507*), son of the preceding.[30]

- 1507–43: Magnus I (*1488–1543*), son of the preceding.

- 1543–71: Francis I (*1510–1581*), son of the preceding, resigned in favour of his son Magnus II.[31]

- 1571-74: Magnus II (*1543–1603*), son of the preceding.[32]

- 1574–81: Francis I (*1510–1581*), reascended the throne, replacing his son Magnus II.

- 1581-88: Magnus II (*1543–1603*), son of the preceding, ruled jointly with his brothers Maurice and Francis II, Magnus resigned in 1588.

- 1581-1612: Maurice (*1551–1612*), ruled jointly with his brothers Magnus II (till 1588) and Francis II.

- 1581–1619: Francis II (*1547–1619*), ruled jointly with his brothers Magnus II (till 1588) and Maurice (till 1612).[33]

- 1619–56: Augustus (*1577–1656*), son of the preceding.[34]

- 1656–65: Julius Henry (*1586–1665*), brother of the preceding.[35]

- 1665–66: Francis Erdmann (*1629–1666*), son of the preceding.

- 1666–89: Julius Francis (*1641–1689*), brother of the preceding.[36]

House of Welf (1689–1803)

For 113 years the duchy was ruled by members of the Welf dynasty. However, since its violent takeover only in 1728 Emperor Charles VI enfeoffed George II Augustus with Saxe-Lauenburg, finally legitimising the Welfs as dukes.

House of Brunswick and Lunenburg–Celle (1689–1705)

- 1689–1705: George William; also Prince of Brunswick and Lunenburg (Celle), by title also Duke of Brunswick and Lunenburg.

House of Hanover (1705–1803)

- 1705–27: George I Louis; also Prince-Elector of Brunswick and Lunenburg (Calenberg) (commonly called Electorate of Hanover, after its capital), by title also Duke of Brunswick and Lunenburg; also King of Great Britain from 1714.

- 1727–60: George II Augustus; also King of Great Britain, Elector of Hanover, by title also Duke of Brunswick and Lunenburg.

- 1760–1814: George III, de facto dispossessed in 1803–05 and 1805–14, however he held up the title of duke, rejecting any unilateral act and annexation by Napoléon. Only at the Congress of Vienna, where all sides agreed, the title of duke passed to his nephew. Also King of Great Britain (becoming King of Great Britain and Ireland in 1801), Elector of Hanover (becoming King of Hanover in 1814), by title also Duke of Brunswick and Lunenburg.

Napoleonic Wars (1803–14)

- Occupied by the First French Republic, 1803–04.

- Occupied by the First French Empire, 1804–05.

- Recaptured by British, Swedish and Russian forces of the Third Coalition against France, 1805.

- Occupied by the Kingdom of Prussia, 1805–07.

- Occupied by the First French Empire, 1807.

- Annexed to the Kingdom of Westphalia, 1807–10.

- Annexed to the First French Empire, 1810–14.

House of Oldenburg (1814–64)

For fifty years, from 1814, Saxe-Lauenburg was within the German Confederation, and in personal union with the Kingdom of Denmark:

Main line (1814–63)

- 1814–39: Frederick I; also King of Denmark (1808–39, as Frederick VI) and Duke of Schleswig-Holstein; previously King of (1808–14) and Regent of Denmark-Norway from 1784.

- 1839–48: Christian I; also King of Denmark (as Christian VIII) and Duke of Schleswig-Holstein; previously King of Norway (1814, as Christian Frederick).

- 1848–63: Frederick II; also King of Denmark (as Frederick VII) and Duke of Schleswig-Holstein.

Glücksburg line (1863–64)

- 1863–64: Christian II; also King of Denmark (1863–1906, as Christian IX) and Duke of Schleswig-Holstein.

House of Hohenzollern (1865–76)

For twelve years Saxe-Lauenburg was ruled in personal union with Prussia, within the North German Confederation (1867–71). In 1871 Saxe-Lauenburg became a component state of united Germany (German Empire).

- 1865–76: William; also King of Prussia (1861–88), President of the North German Confederation (1867–71) and German Emperor (1871–88).

Dependent rule (1876–present)

- In 1876 the Duchy gave up statehood and was transformed into the District of the Duchy of Lauenburg within Schleswig-Holstein, a province of the Kingdom of Prussia (1866–1918) and then of the Free State of Prussia (1918–33/1947), a component state of the respective government forms of Germany. In 1946 the province assumed the rank of statehood as State (Land) of Schleswig-Holstein and joined the Federal Republic of Germany in 1949.

- In 1890, Imperial Chancellor Otto von Bismarck was awarded the honorific title of Duke of Lauenburg including estates in the Sachsenwald in the former duchy, but he was never sovereign ruler of the territory, which had been incorporated into Prussia in 1876. He moved to these estates in Friedrichsruh and lived there until his death.

In 1988 Prince Lennart von Saxe-Lauenburg died. He claimed the title in 1946 though was no relation of Otto von Bismarck. The claim initially was made in 1921 by his father Peter Johannes Borger van Ammerongen a Dutch nobleman. In the 1690s a court awarded the title to the House of Brunswick and Lunenburg–Celle when the last Duke died without male heirs. There was suspicion at the time that the Judge was bribed. Lennart was succeeded by a nephew.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Saxe-Lauenburg. |

- Historical map of Schleswig Holstein in 1730

- Historical map of Lower Saxony in 1789

- Historical atlas of Saxe-Lauenburg

Notes

- ↑ The House of Wettin also adopted this coat-of-arms when it gained Saxe-Wittenberg, which is why they reappear in the arms of many (formerly) Wettin-ruled states.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 "LAUENBURG", in: Encyclopædia Britannica: 29 vols., 111910–1911, vol. 16 'L to Lord Advocate', p. 280.

- 1 2 Cordula Bornefeld, "Die Herzöge von Sachsen-Lauenburg", in: Die Fürsten des Landes: Herzöge und Grafen von Schleswig, Holstein und Lauenburg [De slevigske hertuger; German], Carsten Porskrog Rasmussen (ed.) on behalf of the Gesellschaft für Schleswig-Holsteinische Geschichte, Neumünster: Wachholtz, 2008, pp. 373-389, here p. 375. ISBN 978-3-529-02606-5

- ↑ Elisabeth Raiser, Städtische Territorialpolitik im Mittelalter: eine vergleichende Untersuchung ihrer verschiedenen Formen am Beispiel Lübecks und Zürichs, Lübeck and Hamburg: Matthiesen, 1969, (=Historische Studien; vol. 406), p. 90, simultaneously: Hamburg, Univ., Diss., 1969.

- ↑ Elisabeth Raiser, Städtische Territorialpolitik im Mittelalter: eine vergleichende Untersuchung ihrer verschiedenen Formen am Beispiel Lübecks und Zürichs, Lübeck and Hamburg: Matthiesen, 1969, (=Historische Studien; vol. 406), pp. 90seq., simultaneously: Hamburg, Univ., Diss., 1969.

- ↑ Elisabeth Raiser, Städtische Territorialpolitik im Mittelalter: eine vergleichende Untersuchung ihrer verschiedenen Formen am Beispiel Lübecks und Zürichs, Lübeck and Hamburg: Matthiesen, 1969, (=Historische Studien; vol. 406), p. 137, simultaneously: Hamburg, Univ., Diss., 1969.

- ↑ However, today's State of Germany named Lower Saxony comprises only small fringes of Lauenburgian Lower Saxon territory, to wit: its areas south of the river Elbe, such as:

i) the Land of Hadeln

ii) a tract of land along the southern Elbe bank, the Marschvogtei, connecting from Marschacht to the Amt Neuhaus

iii) the Amt Neuhaus. - ↑ The addition in edged brackets not in the original. In the German original: "... auch die Höltzung für des Fürstenthumbs Niedersachsen Kern und Brunquell zu achten." Generaldisposition of Julius Francis, 1659.

- ↑ Johann Friedrich Burmester, Beiträge zur Kirchengeschichte der Herzogthums Lauenburg, Ratzeburg: author's edition, 1832, p. 14.

- 1 2 Johann Friedrich Burmester, Beiträge zur Kirchengeschichte der Herzogthums Lauenburg, Ratzeburg: author's edition, 1832, p. 16.

- ↑ Johann Friedrich Burmester, Beiträge zur Kirchengeschichte der Herzogthums Lauenburg, Ratzeburg: author's edition, 1832, p. 18.

- ↑ Johann Friedrich Burmester, Beiträge zur Kirchengeschichte der Herzogthums Lauenburg, Ratzeburg: author's edition, 1832, p. 21.

- ↑ Cordula Bornefeld, "Die Herzöge von Sachsen-Lauenburg", in: Die Fürsten des Landes: Herzöge und Grafen von Schleswig, Holstein und Lauenburg [De slevigske hertuger; German], Carsten Porskrog Rasmussen (ed.) on behalf of the Gesellschaft für Schleswig-Holsteinische Geschichte, Neumünster: Wachholtz, 2008, pp. 373-389, here p. 381. ISBN 978-3-529-02606-5

- 1 2 Cordula Bornefeld, "Die Herzöge von Sachsen-Lauenburg", in: Die Fürsten des Landes: Herzöge und Grafen von Schleswig, Holstein und Lauenburg [De slevigske hertuger; German], Carsten Porskrog Rasmussen (ed.) on behalf of the Gesellschaft für Schleswig-Holsteinische Geschichte, Neumünster: Wachholtz, 2008, pp. 373-389, here p. 380. ISBN 978-3-529-02606-5

- ↑ Johann Friedrich Burmester, Beiträge zur Kirchengeschichte der Herzogthums Lauenburg, Ratzeburg: author's edition, 1832, p. 25.

- ↑ Johann Friedrich Burmester, Beiträge zur Kirchengeschichte der Herzogthums Lauenburg, Ratzeburg: author's edition, 1832, p. 27.

- ↑ Cordula Bornefeld, "Die Herzöge von Sachsen-Lauenburg", in: Die Fürsten des Landes: Herzöge und Grafen von Schleswig, Holstein und Lauenburg [De slevigske hertuger; German], Carsten Porskrog Rasmussen (ed.) on behalf of the Gesellschaft für Schleswig-Holsteinische Geschichte, Neumünster: Wachholtz, 2008, pp. 373–389, here p. 379. ISBN 978-3-529-02606-5

- ↑ Johann Friedrich Burmester, Beiträge zur Kirchengeschichte der Herzogthums Lauenburg, Ratzeburg: author's edition, 1832, p. 15.

- 1 2 Cordula Bornefeld, "Die Herzöge von Sachsen-Lauenburg", in: Die Fürsten des Landes: Herzöge und Grafen von Schleswig, Holstein und Lauenburg [De slevigske hertuger; German], Carsten Porskrog Rasmussen (ed.) on behalf of the Gesellschaft für Schleswig-Holsteinische Geschichte, Neumünster: Wachholtz, 2008, pp. 373–389, here p. 382. ISBN 978-3-529-02606-5

- 1 2 Cordula Bornefeld, "Die Herzöge von Sachsen-Lauenburg", in: Die Fürsten des Landes: Herzöge und Grafen von Schleswig, Holstein und Lauenburg [De slevigske hertuger; German], Carsten Porskrog Rasmussen (ed.) on behalf of the Gesellschaft für Schleswig-Holsteinische Geschichte, Neumünster: Wachholtz, 2008, pp. 373-389, here p. 383. ISBN 978-3-529-02606-5

- ↑ Johann Friedrich Burmester, Beiträge zur Kirchengeschichte der Herzogthums Lauenburg, Ratzeburg: author's edition, 1832, p. 41.

- 1 2 3 4 Johann Friedrich Burmester, Beiträge zur Kirchengeschichte der Herzogthums Lauenburg, Ratzeburg: author's edition, 1832, p. 66.

- ↑ Johann Friedrich Burmester, Beiträge zur Kirchengeschichte der Herzogthums Lauenburg, Ratzeburg: author's edition, 1832, p. 96.

- ↑ Johann Friedrich Burmester, Beiträge zur Kirchengeschichte der Herzogthums Lauenburg, Ratzeburg: author's edition, 1832, p. 47.

- ↑ Johann Friedrich Burmester, Beiträge zur Kirchengeschichte der Herzogthums Lauenburg, Ratzeburg: author's edition, 1832, p. 49.

- ↑ Johann Friedrich Burmester, Beiträge zur Kirchengeschichte der Herzogthums Lauenburg, Ratzeburg: author's edition, 1832, p. 51.

- ↑ Pommern, Werner Buchholz (ed.), Werner Conze, Hartmut Boockmann (contrib.), Berlin: Siedler, 1999, pp. 363 seq. ISBN 3-88680-272-8

- ↑ His wife was Sophia of Brunswick and Lunenburg (Wolfenbüttel) and they had Catharina of Saxe-Lauenburg (mar. Henry IV, Duke of Mecklenburg-Schwerin) as daughter.

- ↑ His wife was Adelheid of Pomerania and they had Sophie of Saxe-Lauenburg (*before 1428-1473*) as daughter, married to Gerhard VII, Duke of Juliers.

- ↑ His wife was Dorothea of Brandenburg (c. 1446 – March 1519, daughter of Frederick II, Elector of Brandenburg). Their children were Eric of Saxe-Lauenburg (1472 - 20 October 1522, as Eric I Prince-Bishop of Münster, as II Prince-Bishop of Hildesheim) and Sophia of Saxe-Lauenburg (mar. in ca. 1420, d. 1462, mother of Eric II, Duke of Pomerania).

- ↑ He married on 8 February 1540 Sybille of Saxe-Freiberg (Freiberg, 2 May 1515 - 18 July 1592, Buxtehude), daughter of Henry IV of Saxe-Wittenberg. Their children were Henry of Saxe-Lauenburg (as Henry II Prince-Bishop of Osnabrück, as III Prince-Archbishop of Bremen and as IV Prince-Bishop of Paderborn), Sidonia Katharina of Saxe-Lauenburg (mar. with Wenceslaus III Adam, Duke of Cieszyn) and Ursula of Saxe-Lauenburg-Ratzeburg (mar. with Henry, Duke of Brunswick and Lunenburg (Dannenberg)).

- ↑ His wife was Sophia of Sweden.

- ↑ Francis' wife was Mary of Brunswick and Lunenburg (Wolfenbüttel) (1566-1626, daughter of Julius, Duke of Brunswick and Lunenburg (Wolfenbüttel)) and they had daughters Juliane of Saxe-Lauenburg (26 December 1589 - 1 December 1630, mar. 1 August 1627), married to Friedrich, Duke of Schleswig-Holstein-Sonderburg-Norburg, and Sophie Hedwig of Saxe-Lauenburg (24 May 1601 - 1 February 1660, mar. 23 May 1624) with Philipp, Duke of Schleswig-Holstein-Sonderburg-Glücksburg.

- ↑ His wife was Elisabeth Sophie of Holstein-Gottorp, daughter of John Adolf, Duke of Holstein-Gottorp. Their daughter was Anna-Elisabetha of Saxe-Lauenburg (23 August 1624 - 1688, mar. 2 April 1665), wife of William Christoph, Landgrave of Hesse-Homburg.

- ↑ He married three times: 1) Anne of Ostfriesland, 2) on 27 February 1628 Elisabeth Sophia of Brandenburg (13 July 1589–24 December 1629), daughter of John George, Elector of Brandenburg and mother of Duke Francis Erdmann, and 3) on 18 August 1632 Anna Magdalene, Baroness Popel von Lobkowitz (d. 7 September 1668), the only to ascend with him to the throne on 18 January 1656. She was mother of Duke Julius Francis.

- ↑ His wife was Hedwig of Palatine Sulzbach (15 April 1660 - 23 November 1681; daughter of Christian Augustus, Count Palatine of Sulzbach) and they had Anna Maria Franziska of Saxe-Lauenburg and Sibylle Auguste of Saxe-Lauenburg as daughters.

-de.svg.png)