Sassoon Eskell

| Sir Sassoon Eskell KBE | |

|---|---|

| ساسون حسقيل | |

|

Sir Sassoon Eskell | |

| Deputy for the Iraqi Parliament | |

|

In office 1925–1932 | |

| Monarch | Faisal I of Iraq |

| Constituency | Baghdad |

| Minister of Finance | |

|

In office 1 September 1921 – 1925 | |

| Monarch | Faisal I of Iraq |

| Prime Minister |

Yasin al-Hashimi Jafar al-Askari Abd al-Muhsin as-Sa'dun Abd Al-Rahman Al-Gillani |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Sassoon Eskell 17 March 1860 Baghdad, Ottoman Iraq |

| Died |

31 August 1932 (aged 72) Paris, France |

| Resting place | Père Lachaise Cemetery, Paris |

| Citizenship | Iraqi |

| Profession | Statesman, Financier |

Sir Sassoon Eskell, KBE (17 March 1860 – 31 August 1932) was an Iraqi statesman and financier.[1] Also known as Sassoon Effendi[2][3] (from Turkish Effendi, a title meaning Lord). Regarded in Iraq as the Father of Parliament,[4] Sir Sassoon (Arabic: ساسون حسقيل or ساسون حزقيال) was the first Minister of Finance in the Kingdom and a permanent Member of Parliament until his death. Along with Gertrude Bell and T. E. Lawrence, he was instrumental in the creation and the establishment of the Kingdom of Iraq post Ottoman rule,[5] and he founded the nascent Iraqi government’s laws and financial structure.[4]

He was knighted by King George V in 1923.[6][7] King Faisal I conferred on him the Civil Rafidain Medal Grade II, the Shahinshah awarded him the Shirokhorshid Medal and the Ottoman Empire decorated him with the Al-Moutamayez Medal.[4]

Early life

Scion of an ancient, distinguished and aristocratic Jewish family of great affluence, the Shlomo-David’s,[4][6] Sassoon was born on 17 March 1860 in Baghdad, Iraq. He was a cousin of the celebrated English war poet and author Siegfried Sassoon, through their common ancestor, Heskel Elkebir (1740–1816).[8] His father was Hakham Heskel, Shalma, Ezra, Shlomo-David, a student of Hakham Abdallah Somekh.[9][10] In 1873 Heskel travelled to India to become the Chief Rabbi and Shohet of the thriving Baghdadi Jewish Community there. In 1885 he returned to Baghdad as the leading rabbinical authority[7] and a great philanthropist. A wealthy man, in 1906 he built Slat Hakham Heskel, one of the most prominent synagogues in Baghdad.[9][10]

Sassoon obtained his primary education at the Alliance Israélite Universelle[7] in Baghdad. In 1877, at age 17, he travelled to Constantinople to continue his education, accompanied by his maternal uncle, the immensely wealthy magnate and land owner Menahem Saleh Daniel[11][12] who was elected deputy for Baghdad to the first Ottoman Parliament in 1876 during the reign of Sultan Abdul Hamid II and later became Senator of the Kingdom of Iraq (1925–1932). Sassoon then went to London and Vienna at the Diplomatic Academy of Vienna to receive his higher education in economics and law.[1] He was known to have been an outstanding student.[9] He finally returned to Constantinople to obtain another law degree.[1]

Formative career

Following his education abroad and fluent in nine languages (English, Arabic, Turkish, Persian, Hebrew, French, German, Greek and Latin)[4][7] Sassoon returned to Baghdad in 1881 where he was appointed Dragoman for the vilayet of Baghdad, in which post he remained until 1904. In 1885, he was also appointed Foreign Secretary to the Wali (Governor-General).[1] On the announcement of the new Ottoman Constitution in 1908, he was elected deputy for Baghdad in the first Turkish Parliament,[3] a position he occupied until the end of World War I, when Iraq was detached from the Ottoman Empire in 1918. In the Ottoman Parliament he worked as a member of various committees and organizations including the Committee of Union and Progress (the "Young Turks" party) and was Chairman of the Budget Committee. He was deputed to London and Paris on special missions, including as a member of an Ottoman delegation to London in 1909 as under-secretary of state for trade and agriculture. In 1913 he was appointed Advisor to the Ministry of Commerce and Agriculture.

Gertrude Margaret Lowthian Bell referred to him and his brother Shaoul in a letter to her father dated 14 June 1920, as follows:

“I'm making great friends with two Jews, brothers—one rather famous, as a member of the Committee of Union and Progress and a deputy for Baghdad. His name is Sasun Eff. The other Sha'al, (which is Saul) is the leading Jew merchant here. They have recently come back from C'ple [Istanbul (Constantinople)]—they were at the first tea party I gave for you, here. I've known Sha'al's wife and family a long time—they are very interesting and able men. Sasun, with his reputation and his intelligence, ought to be a great help.”

Bell also wrote of Sassoon on 17 October 1920:

“That night Mr Philby dined with me and we had a long and profitable talk. He had been to tea with me also and I had Sasun Eff. to meet him which was most valuable, for Sasun is one of the sanest people here and he reviewed the whole position with his usual wisdom and moderation.”

The creation of Post WWI Iraq

In 1920, after the end of the First World War, Sassoon returned to Baghdad from Istanbul and was appointed Minister of Finance in the first Iraqi government, a new provisional government under the premiership of Abd Al-Rahman Al-Naqib. The importance of his role was what was to make or break the new constitution of Iraq. The details of this were highlighted by Gertrude Bell when she recounted the circumstances regarding the establishment of Iraq’s new government. Dated 1 November 1920, Bell wrote:

“On Wednesday morning all seemed to be going well. In the afternoon Major Yetts and I went out sightseeing in Baghdad and on our way home dropped in to tea with the Tods. Mr Tod sprung upon us that he had called on Sasun Eff to congratulate him on his becoming Minister of Finance and found him with Hamdi Pasha Baban (who had been offered a seat in the Cabinet without portfolio,) both in the act of refusing. Mr Tod had done his best to persuade them but had heard in the afternoon that they had refused, the real, though not the expressed reason, being that they would not join a Cabinet which contained Saiyid Talib.While both were important, Sasun Eff was absolutely essential. His refusal would damn the Cabinet as a Talib ministry and doom it to failure from the outset. I left my cup of tea undrunk and rushed back to the office to tell Mr Philby. He wasn't there, but there was a light in Sir Percy's room. I went in and told him. He bade me go at once to Sasun Eff and charged me to make him change his mind. I set off feeling as if I carried the future of the 'Iraq in my hands, but when I got to Sasun's house to my immense relief I found Mr Philby and Capt Clayton already there. The Naqib had got Sasun's letter and had sent Mr Philby off post haste. I arrived, however, in the nick of time. They had exhausted all their arguments and Sasun still adhered to his decision. I think my immense anxiety must have inspired me for after an hour of concentrated argument he was visibly shaken, in spite of the fact that his brother Sha'al (whom I also admire and respect) came in and did his best against us. Finally however we persuaded him that Sir Percy had no desire to thrust Talib or anyone else upon Mesopotamia, but that Talib like everyone else must be given his chance. If he proved valuable he would take his part in the foundation of national institutions, if not he was politically a dead man. We got Sasun Eff to consent to think it over and to come and see Sir Percy next day. I had an inner conviction that the game was won—partly, thank heaven, to the relations of trust and confidence which I personally had already established with Sasun—but we none of us could feel sure. You will readily understand that I didn't sleep much that night. I turned and turned in my mind the arguments I had used and wondered if I could not have done better.

Next morning, Thursday, Sasun Eff. came in at 10; I took him straight to Sir Percy and left them. Half an hour later, he returned and told me that he had accepted and I understood the full significance of the Nunc Dimittis. He asked me what he could now do to help and I sent him straight to the Naqib. The leading Shi'ah of Baghdad had also refused to join the Council and it was essential to get him in. In the midst of this talk Sir Percy sent for me. I left Sasun to Mr Philby and went to consult with Sir Percy. We agreed that I should send at once for Ja'far, tell him what had happened and bid him bestir himself. It was past one o'clock before I caught Ja'far. We had the most extraordinary conversation. He told me he had come into the Cabinet, only to defeat Talib, that he distrusted and loathed him and regarded it as shameful that he should be one of the leading persons of Mesopotamia. I said that the Mesopotamians themselves had made him, by their fear and their servility, and that it was for them to unmake him if they wished. We then discussed how to win over the extremists, I assured him that that was Sir Percy's chief desire and taking heart, he asked if he might talk to Sir Percy. I took him at once to Sir Percy and left them together, with the assured conviction that Sir Percy was the best exponent of his own policy.”… “Oh, if we can pull this thing off! rope together the young hotheads, and the Shi'ah obscurantists, and enthusiasts like Ja'far, polished old statesmen like Sasun, and scholars like Shukri—if we can make them work together and find their own salvation for themselves, what a fine thing it will be. I see visions and dream dreams. But as we say in Arabic countless times a day "Through the presence of His Excellency the Representative of the King, and with the help of the Great Government, all please God, must be well!"

“The Council of State of the first Arab government in Mesopotamia since the (thirteenth century) Abbasid’s” as Bell described it, met on Tuesday, 2 November 1920. Along with Sassoon as Minister of Finance, Jafar Pasha al-Askari as Minister of Defence and six other ministers including Sayid Talib as Minister of the Interior.[13] The next step was to choose a King to unite the tribally fractured country. Sassoon had already offered his opinions on the matter as was recounted again by Miss Bell:

Seated: far right: Winston Churchill, second from left: Field Marshal Edmund Allenby, 1st Viscount Allenby

Standing row above: far left: Gertrude Bell, second from left: Sassoon Eskell, far right: Jafar Pasha al-Askari

“I had a long and interesting talk with Sasun Eff. the other day—I went to call on his sister in law and found all the men there eager to embark on talk. Sasun Eff. said he felt sure that no local man would be acceptable as head of the state because every other local man would be jealous of him. He went on to throw out feelers in different directions—one might think of a son of the Sharif, or a member of the family of the Sultan of Egypt, if there was a suitable individual, or of the family of the Sultan of Turkey? I said I for my part felt sure that Sir Percy didn't and couldn't mind whom they selected except that I thought the Turkish family was ruled out—it ought to be an Arab prince. Sasun Eff. said "If they think you are backing S. Talib they will all agree outwardly to S. Talib, whatever they think of him. I remember when once I happened to be on the same boat with him coming back from Constantinople [Istanbul]—it was when S. Talib was a deputy. Almost without exception the people of Basrah hated and feared him, and if you'll believe me they all came down to Muhammarah to welcome him! and the ones that hated him most gave him the most cordial reception. They were afraid of him. So it would be now." I again insisted that we could find no interest or advantage in backing anyone; it was entirely a matter for the people themselves to decide, but whether he believed me or not I can't say. He had, however, hit on the root of the matter. Anyone they think we're backing they will agree to—and then intrigue against him without intermission. It's not an easy furrow to plough!”

To reach a final conclusion on the choice for ruler Winston Churchill, then British colonial secretary, summoned a small group of Orientalists to Egypt for the famous Cairo Conference[14] of March 1921. The British Empire’s best minds on the Middle East would determine the fate of Mesopotamia, Transjordan and Palestine. Churchill’s objectives were to save money by reducing Britain's overseas military presence; Find a way to maintain political control over Britain's mandate areas as identified in the Sykes-Picot Agreement; Protect what was then suspected to be substantial oil reserves in Iraq; and lastly preserve an open trade route to India, the Crown Jewel of the empire.[15] Representing the Iraqis, two members of the Council were picked to join the delegation: Sassoon Eskell and Jafar Pasha al-Askari; with the disliked Sayid Talib left behind. It was at this conference, with Sassoon’s and Jafar Pasha’s approval[13] that Emir Faisal was chosen for the throne of Iraq.

Ministerial office

When Faisal I was enthroned as King of Iraq, a new ministry was formed on 1 September 1921 by Prime Minister Abd Al-Rahman Al-Naqib in which Sassoon was re-appointed Minister of Finance. He was re-appointed Minister of Finance again in five successive governments[3] until 1925 of Abd Al-Rahman Al-Naqib, Abd Al-Muhsin Al-Sa’dun and Yasin Pasha Al-Hashimi.

Gertrude Bell described Sassoon’s ministerial qualities in another letter dated 18 December 1920:

“The man I do love is Sasun Eff. and he is by far the ablest man in the Council. A little rigid, he takes the point of view of the constitutional lawyer and doesn't make quite enough allowance for the primitive conditions of the 'Iraq, but he is genuine and disinterested to the core. He has not only real ability but also wide experience and I feel touched and almost ashamed by the humility with which he seeks—and is guided by—my advice. It isn't my advice, really; I'm only echoing what Sir Percy thinks. But what I rejoice in and feel confident of is the solid friendship and esteem which exists between us. And in varying degrees I have the same feeling with them all. That's something, isn't it? that's a basis for carrying out the duties of a mandatory?”

And again in correspondence dated 7 February 1921:

“I do love Sasun Eff; I think he is out and away the best man we've got and I am proud and pleased that he should have made friends with me. He is an old Jew, enormously tall and very thin; he talks excellent English, reads all the English papers, and is entirely devoid of any self-interest. He has no wish to take any further part in public life but he says he is convinced that the future of his country—if it is to have a future—is bound up with the British mandate and as long as we say he can help us he is ready to put himself at our service. He made a very considerable name in the Turkish Chamber where he sat as a strong Committee man. Some day I mean to make him tell me all he really thought about the Committee. One can talk to him as man to man, and exchange genuine opinions”

Seated in the centre: Sir Sassoon Eskell with King Faisal I immediately to his left. The tycoon, Senator Menahem Saleh Daniel is seated on the far right of this shot.

During his period as Minister of Finance, Sassoon founded all the financial and budgeting structures and laws for the Kingdom and looked whole-heartedly after the interests of the monarchy and the proper fulfilment of its laws.[4] Rather famously, one of his most financially prolific deeds for the State was during negotiations with the British Petroleum Company in 1925.[1][3][7] Through a pure stroke of genius and foresight, Sir Sassoon demanded that Iraq’s oil revenue be remunerated in gold rather than sterling; at the time, this request seemed bizarre since sterling was backed by the gold standard. Nevertheless, his demand was reluctantly accepted. Later this concession benefited Iraq’s treasury during World War II, when the gold standard was abandoned and sterling plummeted. He thus secured countless additional millions of Iraqi dinars for the State. This is something that the Iraqi nation remembers with appreciation and admiration.

In 1925 he was elected deputy for Baghdad in the first parliament of the Kingdom and was re-elected to all successive parliaments until his death. In the Iraqi parliament he was chairman of the financial committee and was regarded as the Father of Parliament, in light of his vast parliamentary knowledge, depth of experience and venerable age.[4] His advice was taken on all parliamentary matters. He arbitrated and his views were accepted, whenever a conflict arose concerning the enforcement of internal regulations. He was a far-sighted statesman with a profoundly deep knowledge of Iraq and other countries. He was immensely well travelled and was well acquainted with most major European statesmen of the time.[4]

Death

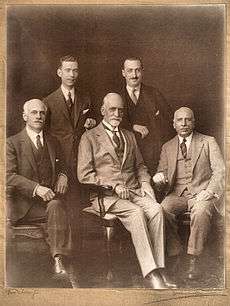

seated left to right: Jack Eskell; Sir Sassoon Eskell; Henry Eskell

standing: David Shaoul Eskell; Frederick Daniel

Sir Sassoon died in Paris, France on 31 August 1932 while undergoing medical treatment. He was buried at the Père-Lachaise cemetery on Boulevard de Ménilmontant in Paris. On 7 September 1932, a commemorative service was held in Baghdad in his memory. Prime Minister Yasin Pasha Al-Hashimi published a eulogy in an Arabic daily newspaper in which he praised the late Sir Sassoon’s character, culture, his outstanding personality, his vast knowledge, sense of duty and the proper fulfilment of that duty no matter how great the sacrifice was in time or in life. He said that the stupendous efforts which had been exerted by the deceased in regulating and establishing on a solid footing, the affairs of the Kingdom of Iraq during the mandatory regime, will be remembered by future generations. All leading Arabic daily newspapers similarly eulogised the late Sir Sassoon’s character and achievements, saying that the services which had been rendered by the deceased for the welfare of his country will immortalise his great name, adding that his death was an irreparable loss to the nation.[4]

Kfar Yehezkel in the Jezreel Valley is named after him, for donating money to the Jewish National Fund.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 "The Scribe – Journal of Babylonian Jewry, October 1986, Issue 20, p.7" (PDF).

- ↑ "The Gertrude Bell Project: Bell’s letter to her father dated 14 June 1920".

- 1 2 3 4 "HebrewHistory.Info - Hebrew History Federation Fact Paper 31: Iraq, A Three Thousand Year Old Judaic Homeland by Samuel Kurinsky".

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Bekhor, Gourji C. (1990). Fascinating Life and Sensational Death. Israel: Peli Printing Works Ltd. p. 41.

- ↑ "The Gertrude Bell Project: Bell’s letter to her father dated 1 November 1920".

- 1 2 "Les Fleurs de l'Orient - The Genealogy Site: Sasson Eskel".

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Answers.Com, Mideast & N. Africa Encyclopedia: Sasson Heskayl".

- ↑ "Les Fleurs de l'Orient - The Genealogy Site: Sir Sassoon Eskell & Siegfried Sassoon".

- 1 2 3 "The Scribe – Journal of Babylonian Jewry, Autumn 2000, Issue 73, p.52" (PDF).

- 1 2 "Les Fleurs de l'Orient - The Genealogy Site: Heskel Shlomo-David".

- ↑ Kedourie, Professor Elie (1974). Arabic Political Memoirs and other studies. Great Britain: Frank Cass and Company Ltd. p. 268. ISBN 0-7146-3041-1.

- ↑ "The Gertrude Bell Project: Bell’s letter to her father dated 20 February 1924 and 26 November 1925".

- 1 2 Wallach, Janet (1996). Desert Queen. Great Britain: Weidenfeld & Nicholson. p. 298. ISBN 0-7538-0247-3.

- ↑ "Answers.Com, Cairo Conference (1921)".

- ↑ "Russell, James A. (October 2002) Odium of the Mesopotamia Entanglement. Strategic Insights, Volume I, Issue 8".